Work-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has received widespread attention among military personnel, first responders, and emergency health care workers, whose jobs put them at elevated risk for the condition (

1,

2). Institutional health care workers, however, face PTSD rates similar to those faced by emergency responders after natural disasters, epidemics, or violence (

3). Among nursing staff, trauma-related disorders can lead to compassion fatigue (

4), reduced productivity (

5), disengagement from patient care (

6), patient falls, medication errors, and overall lower quality of care (

7). Workplace-related trauma symptoms have been associated with experiencing or witnessing violence (

8), including among nurses in hospital and community health care settings (

5,

9,

10). In this study, we examined PTSD symptoms among hospital-based psychiatric nurses and other clinical staff.

Violence may be particularly common in psychiatric settings (

11). One review reported that 30% to 76% of psychiatric workers have been assaulted during their careers (

12). However, little is known about psychiatric staff’s vulnerability to PTSD. In a survey of inpatient ward staff at one Canadian psychiatric hospital, most (82%) reported exposure to violence, which was related to self-reported PTSD symptoms (

13). Among 201 mental health staff at a psychiatric hospital in Botswana, 35% had been assaulted during the past year, and 18% met criteria for PTSD; violence exposure was related to PTSD diagnosis (

9). The effect of the type of violence (e.g., assault, threat, accident) and level of exposure (e.g., directly assaulted, witnessed assault, responded to assault) on PTSD symptoms has yet to be explored.

Most research on exposure to violence in health care institutions has focused on nurses (

14), who have reported higher scores on a measure of PTSD symptoms than other staff (

13). Nursing staff are also more likely than other workers to be exposed to more chronic sources of stress in terms of witnessing disturbing patient behaviors, such as constant screaming, physical resistance to care, and self-injury (

13). However, it is unknown whether the frequency of exposure to such behavior affects PTSD symptoms. Nonnursing health care staff may also be assaulted (

15) or indirectly exposed to traumatic events and to related risks of secondary trauma (

16) and PTSD (

9,

13). These findings suggest the need to broaden the scope of research to nonnursing disciplines and to explore the effect of exposure to both critical events and chronic stressors.

Even within the nursing profession, men are more likely than women to experience workplace violence (

17). Men have a higher prevalence than women of exposure to most potentially traumatic critical events, excluding sexual assault, yet women are twice as likely as men to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD, whether in epidemiologic samples or in samples selected for exposure to critical events (

18). Among public safety personnel, more women than men screened positive for PTSD or any mental disorder (

1). Among clinicians, women are more vulnerable to secondary trauma (

16). In a previous study of gender and exposure to violence among mental health care providers, PTSD was associated with both exposure to violence and gender (

9). Thus, there are substantial grounds for gender-based analyses of workplace violence and its effects.

The purpose of this study was to investigate exposure in the psychiatric workplace to critical events (violence, threats, or death) and chronic stressors in the course of patient care and the association of such events with self-reported PTSD symptoms. PTSD was not clinically diagnosed. We also examined whether gender and professional discipline were associated with exposure to critical events or chronic stressors, with the prevalence of PTSD symptoms, or with the relation between the two. We hypothesized that nursing staff would report more exposure to critical events than nonnursing staff and would score higher on a measure of PTSD symptoms (hypothesis 1), that men would report more exposure to critical events than women but would score lower on the measure of PTSD symptoms (hypothesis 2), and that symptoms would be statistically explained by exposure to critical events, exposure to chronic stressors, professional discipline, and gender (hypothesis 3).

Methods

We surveyed workers on inpatient psychiatric units at three psychiatric hospitals in Canada. The hospitals provided both forensic and nonforensic psychiatric inpatient services and served both urban and rural communities.

Sample

All staff working with inpatients were eligible to participate in the survey. We included nursing staff (registered nurses, practical nurses, and patient care assistants), physicians, allied health professionals (e.g., occupational therapists, psychologists, recreational therapists, and social workers), clinical managers, and staff who worked with inpatients in off-ward areas. The 761 participants (69% female) included 430 (57%) nursing staff and had worked in mental health for an average of 6 to 10 years. The 761 participants represented 62% of 1,230 estimated eligible staff.

Procedure

Research protocols were reviewed and approved by the hospitals’ institutional review boards. The secure online version of the survey was accessible for 2 months at each site in 2017–2018. We discussed the study with hospital administrators and clinical managers prior to releasing the survey, and then e-mailed survey invitations to the staff. We also attended inpatient units, where we encouraged staff to complete the survey with tablet computers or on hard copies. We offered all participants a $10 gift card and gave in-person participants a list of in-hospital and online mental health support resources.

Variables

After we explained the study procedures, participants checked a box to indicate consent. The survey began with questions about respondents’ number of years of work experience in mental health, professional discipline (nursing, allied health, or other), type of inpatient unit (forensic, nonforensic), and gender identity. All questions included “other” and “prefer not to answer” response options.

Critical events were defined based on clinical diagnostic criteria for PTSD in

DSM−5 (

19). We included eight events: physical assault by a patient with no physical injury sustained, physical assault by a patient that resulted in an injury or death, injury of a staff member while restraining a patient, sexual assault by a patient, threat of death or serious injury to staff, threat of death or serious injury to staff’s family, violent or accidental death, and a suicide or a near fatal attempt. For each item, participants responded: “It happened to me directly”; “I responded to the code or call for help”; “I witnessed it (by being present on the unit or any workplace location where you saw or heard the event or its effect on anyone involved)”; “I learned about it happening to a close colleague/friend at work”; “I was repeatedly exposed to details about it as part of my job (by investigating or reporting details of violent acts that resulted in serious injury)”; or “Does not apply to me.” We created a critical event score by summing the number of events experienced (range 0–8).

To elicit data on chronic stressors, we asked, “In the past year, while at work, how often were you exposed to the following behaviors by patients?” The list of 14 behaviors was taken from Hilton and colleagues’ (

13) survey of disturbing behaviors by psychiatric patients: damaging the room, drinking from the toilet, eating harmful items, eloping, flooding the room, hoarding, resisting care physically, screaming constantly, injuring themselves, engaging in public sexual behavior, smearing feces, wandering, issuing verbal abuse or threats, and conducting acts of physical violence. Instead of asking whether the participant had ever experienced a behavior, we asked the participants to indicate the frequency of their experiences (0, never; 1, a few times a year or less; 2, once a month or less; 3, a few times a month; 4, once a week; 5, a few times a week; or 6, every day). We then counted the number of chronic stressors endorsed and also calculated a total chronic stressor frequency score.

Symptoms were measured by using the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) (

20), which has 20 self-report items rated 0, not at all, to 4, extremely, according to how much respondents have been bothered by each symptom during the past month. The PCL-5 yields symptom cluster subscores (re-experiencing, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, and arousal); a total cutoff score of 33 has optimal diagnostic efficiency (

21). To capture the

DSM-5 symptom duration criterion of at least 1 month, we asked participants, “For how long have you been bothered by these difficulties?” Possible responses included “not at all,” “less than 7 days,” “7 days to 1 month,” and “more than 1 month.” We measured impairment in social, occupational, and other areas of functioning, consistent with diagnostic criteria, using section 4 of the Diagnostic Interview for Adjustment Disorder (DIAD) (

22) adapted for self-report. Respondents rated the impact of signs and symptoms in the past week (0, no impairment, to 10, serious impairment) on housekeeping, job, study, close friendships, and social contacts. The DIAD has been shown to be a valid instrument for diagnosing adjustment disorders (

22).

Results

Of 849 submitted surveys, we excluded 77 that were incomplete for critical events, chronic stressors, or the PCL-5 score; another 11 were excluded for inconsistent responding. Of the resulting total of 761, roughly equal numbers of participants had worked in mental health for 1 to 5 years (N=205, 27%), 11 to 20 years (N=191, 25%), and more than 20 years (N=161, 21%), with fewer having worked in mental health for 6 to 10 years (N=133, 18%) or for less than 1 year (N=64, 8%); seven (1%) did not answer the question about number of years spent working in mental health.

Nursing was the most common discipline reported (N=430, 57%), followed by allied health (N=203, 27%). The 107 (14%) participants who identified their discipline as “other,” and 21 (3%) who did not answer the question, were excluded from the analyses involving category of professional discipline. Most participants (N=524, 69%) reported being female, followed by 227 (30%) who reported being male. The 10 (1%) who reported other identity or did not answer the question about gender were excluded from the analyses involving gender.

Almost all staff (N=733, 96%) reported having been exposed to at least one critical event: a physical threat, assault, or death that may have constituted a traumatic event. Most staff (N=513, 67%) reported at least one direct exposure.

Eighty-six percent of the participants (N=655) reported exposure to at least one chronic stressor, most commonly verbal abuse, constant screaming, or physical resistance to care (

Table 1). The count of chronic stressors and the total chronic stressor frequency score were significantly associated with exposure to any critical event (r=0.54 and r=0.48, respectively, p<0.001) and with the critical event score (r=0.31 and r=0.23, respectively, p<0.001). The remaining analyses of chronic stressors pertain to the chronic stressor count only.

Prevalence of PTSD Criteria

The mean±95% confidence interval of participants’ PCL-5 total score was 15.40±1.15 (

Table 2), with a range of 0 to 80 (kurtosis=1.18, SE=0.18; skew=1.26, SE=0.09).

Table 2 shows the participants’ PCL-5 cluster subscale scores. Nursing staff reported higher scores than allied health staff on the PCL-5 (18.18±1.58 versus 12.02±2.01; F=13.95, df=1 and 624, p<0.001, partial η

2=0.022).

Sixteen percent of the participants (N=125) scored zero on the PCL-5, and 16% (N=118) met the screening cutoff score of at least 33. Nearly half (N=370, 49%) reported having been bothered by PTSD symptoms for more than 1 month. We calculated whether participants met the more stringent criteria for PTSD (reporting any critical event, PCL-5 score of at least 33, at least one symptom in each symptom cluster, symptom duration of over 1 month, and at least one impairment rated at least 5). By using this method, we determined that 71 participants (9%) met full criteria for PTSD, although we did not clinically diagnose PTSD.

Exposure to Critical Events and PCL-5 Symptoms

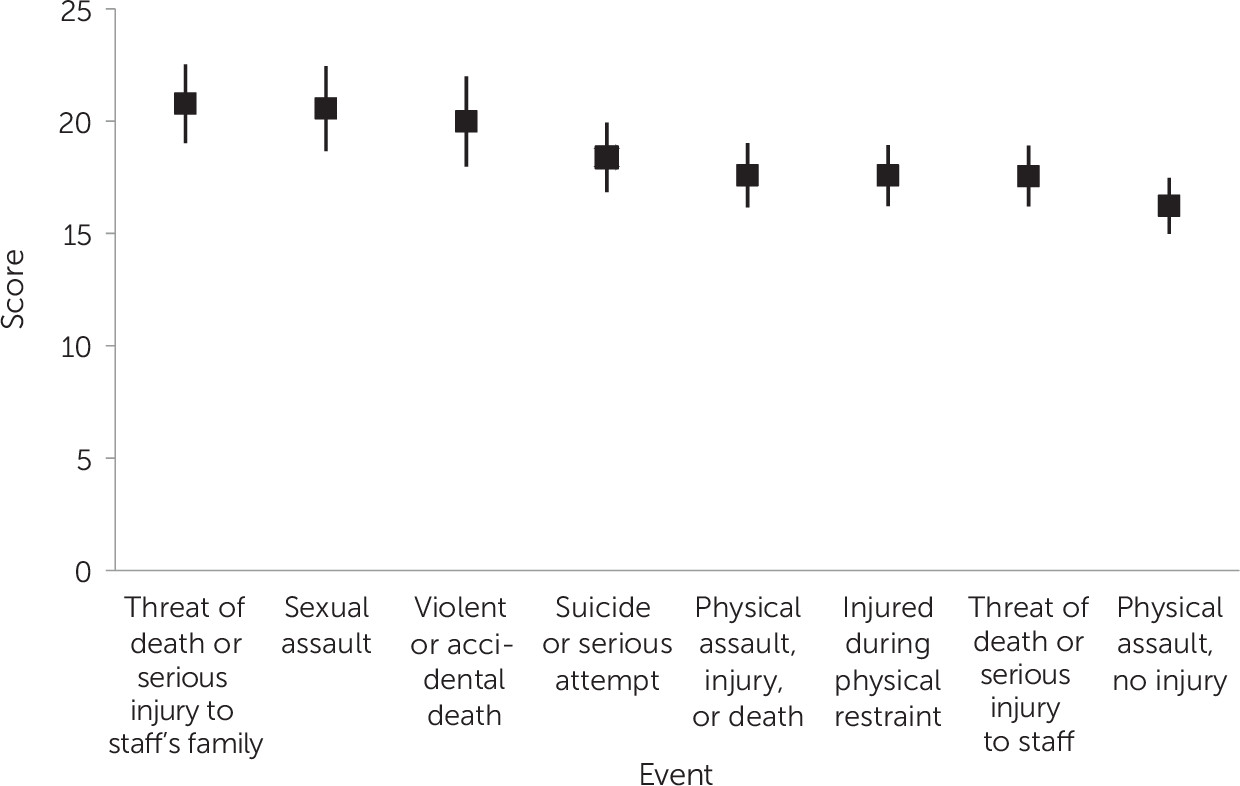

The critical event score was positively correlated with PTSD symptoms (r=0.405, p<0.001), as was each event (

Table 3). Reported exposure to threats of death or serious injury to staff’s family and to sexual assault yielded higher mean PCL-5 scores than all other events except violent or accidental death (

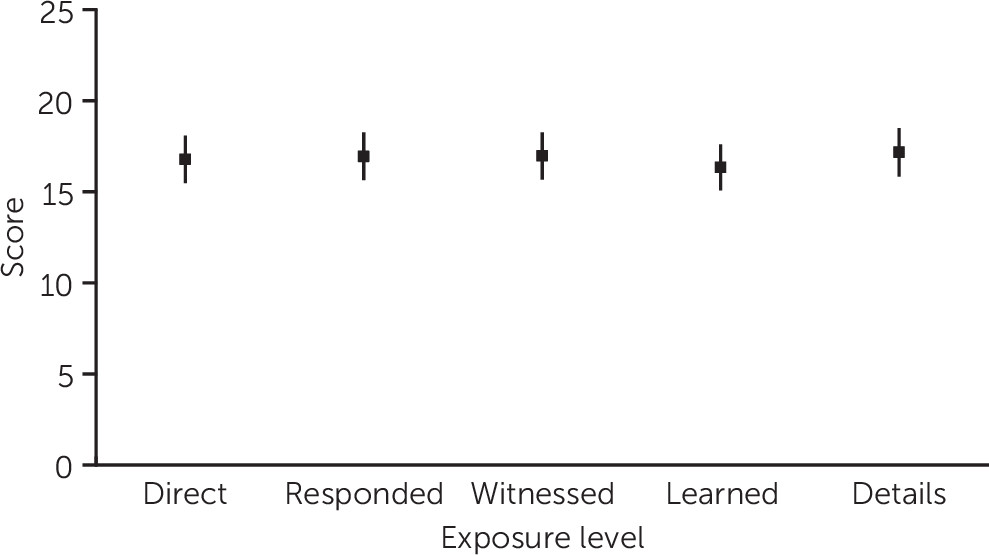

Figure 1). There were no significant differences in symptom scores by level of exposure (

Figure 2).

Contribution of Critical Events, Chronic Stressors, Gender, and Professional Discipline

The regression analysis of the effects of the critical event score, chronic stressor count, professional discipline, and gender on PCL-5 score yielded a model that explained 27% of the variance in PTSD symptoms (F=5.39, df=4 and 563, p<0.001, adjusted R2=0.274). The critical event score (β=0.224, t=5.41, p<0.001) and chronic stressor count (β=0.350, t=8.26, p<0.001) were significant contributors to the variance in symptoms. Neither professional discipline nor gender provided additional explanatory power.

The model used to analyze the effect of direct exposure to a critical event explained 21% of the variance in symptoms (F=43.30, df=4 and 563, p<0.001, adjusted R2=0.214). Exposure to critical events (β=0.295, t=7.03, p<0.001) and number of chronic stressors (β=0.246, t=6.14, p<0.001) were significant contributors to PTSD symptoms. Neither discipline nor gender provided additional explanatory power.

Discussion and Conclusions

Among 761 psychiatric staff surveyed, 16% met the PCL-5 screening cutoff score for PTSD. The mean score for the nursing staff, 18.18, is comparable with those of firefighters and municipal police in Canada (

1). When we used more stringent criteria—experience of a critical event, symptoms in all four clusters of the PCL-5, symptom duration of longer than a month, and functional impairment—9% of participants met the criteria for PTSD. This finding indicates that the level of trauma and impairment among mental health care providers in the workplace is of concern. Our results provide an empirical basis for establishing mental health programs for staff in psychiatric settings that provide assessment and treatment of PTSD in addition to basic wellness activities.

PTSD symptoms were associated with exposure to critical events, including physical threats, assaults, or deaths. In addition, and to approximately the same extent, symptoms were associated with reports of chronic stressors, including witnessing patients damaging their rooms, drinking from the toilet, smearing feces, and engaging in public sexual behavior. Some chronic stressors were tied to violent events (e.g., staff injury incurred while removing patients from rooms). Indeed, total counts of critical events were significantly correlated with exposure to chronic stressors, showing that critical events punctuated an already stressed environment.

Nursing staff had higher PCL-5 symptom scores. Nursing staff have more opportunity for exposure to critical events, because they supervise patient activity during 24/7 shifts. However, neither discipline nor gender made a significant contribution to the regression models of the relation between PTSD symptoms and critical events and chronic stressors. It is possible that the need to maintain ongoing professional relationships with long-term patients who sometimes act violently, along with the cumulative effects of chronic stressors, may override any gender effect that might otherwise be present. Future research that further examines the influence of worker and workplace characteristics may help untangle these effects.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of this study is our innovation in considering chronic stressors. Our finding that chronic stressors contribute as much as critical events to staff PCL-5 scores sets the stage for research into the influence of workplace characteristics on the development of PTSD following a traumatic event. Future research could develop psychometrically sound measures of chronic and critical exposures, compared with our rudimentary measures.

Our survey response rate (62%) was higher than that typically observed in workplace surveys, possibly as a result of having the support of both managers and union leaders. We offered staff multiple opportunities and platforms in which to participate in the survey, including an optional paper version, and we intentionally surveyed staff representing different catchment areas (urban versus more rural), psychiatric unit security level (forensic versus nonforensic), and hospital size. However, not all staff participated, and the experiences of those who participated may have differed from those who did not participate, introducing the risk of sample bias. For example, staff who were on leave because of PTSD symptoms or injuries resulting from a workplace incident were not recruited for this study.

As in any study relying on self-report, there is a risk of socially desirable responding, which could lead to minimization or exaggeration of symptoms. Our efforts to assure participant anonymity helped to mitigate this risk. For example, we used categorical rather than continuous response options (e.g., by collapsing all allied health professions into one category and using 5-to-10-year ranges for work experience), and we provided tablet computers for online survey completion so that participants could not be identified by having logged in from their workplace computer.

We did not capture whether PTSD symptoms may have been due to medication, substance use, or other illness. Therefore, the proportion of psychiatric staff satisfying diagnostic criteria for PTSD may be overestimated; further research that uses the exclusion criteria would be of value. Also, we did not control for nonwork exposures and stressors that may have evoked endorsement of PCL-5 symptoms, so the proportion of psychiatric staff satisfying the diagnostic criteria for PTSD may overestimate work-related PTSD. Future research that includes and controls for critical events unrelated to the workplace would be of value.

Implications for Research and Practice

The amount of exposure to critical events reported in this survey of psychiatric staff warrants attention to prevention and protection measures. Almost all staff reported exposure to a physical threat, assault, or death, and two-thirds reported that such events had happened directly to them. The substantial literature on violence risk assessment and management (

14,

23) can inform violence risk reduction in psychiatric hospitals. There is less evidence about the management of threats to staff or their families, which were related to elevated PCL-5 scores in our study. Threats are of particular concern because, although they were among the most common events reported by our participants, they are less systematically recorded and incur less intervention than acts of physical violence. When evaluating efforts to reduce patient aggression, it may be worthwhile to monitor concomitant improvements in staff mental health.

The contribution of both critical events and chronic stressors to PTSD symptoms suggests that workplace interventions may be needed to address cumulative effects of multiple stressors. Emerging evidence suggests that staff training programs can increase personal resilience (

24,

25), and such interventions have been recommended for nurses (

26). Environmental changes to reduce patients’ behavioral challenges, combined with access for staff to mental health professionals qualified to assess and treat PTSD, could benefit both staff and patients.

Whether psychiatric staff members succumb to PTSD may depend not only on exposure to challenging behaviors by patients with acute or chronic illness, but also on workplace characteristics and interactions with coworkers and managers (e.g., physical security, training, trust, procedures for responding to critical events). Future research should examine the relative roles of such variables. We are currently extending this work with an examination of staff’s use of mental health support services and structural and attitudinal barriers to accessing such services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Ontario Public Service Employees Union, the Ontario Nurses’ Association, and the Registered Nursing Association of Ontario for their support and participation in the activities described in this article; the research participants and Rebecca Harris for research assistance; and Della Saunders for comments on an earlier version of this article.