On average, individuals with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, die 15 to 20 years earlier than the general population, and the mortality gap is widening (

1–

3). The leading causes of death for this population are cardiovascular disease and cancer, suggesting that access to timely and appropriate preventive services could help reduce premature deaths. Therefore, gaining a better understanding of issues concerning early cancer detection is an important step in identifying potential causes of early mortality in individuals with serious mental illness.

Breast cancer detection is of particular importance, given that the 5-year survival rate for people with breast cancer is nearly 90%—thanks to substantial efforts to increase awareness and screening among American women (

4). Although there is debate in the field regarding recommendations for mammography screening (

5–

8), the current U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines recommend biennial mammography screening for women ages 50 to 74 (

9).

Unfortunately, evidence suggests that women with serious mental illness may not receive breast cancer preventive services in a timely and appropriate way (

10). Recent work has found that breast cancer is identified at later stages among women with serious mental illness compared with women without these disorders (

11). As a result, breast cancer among women with serious mental illness is characterized by larger and higher-grade tumors and more lymph node involvement.

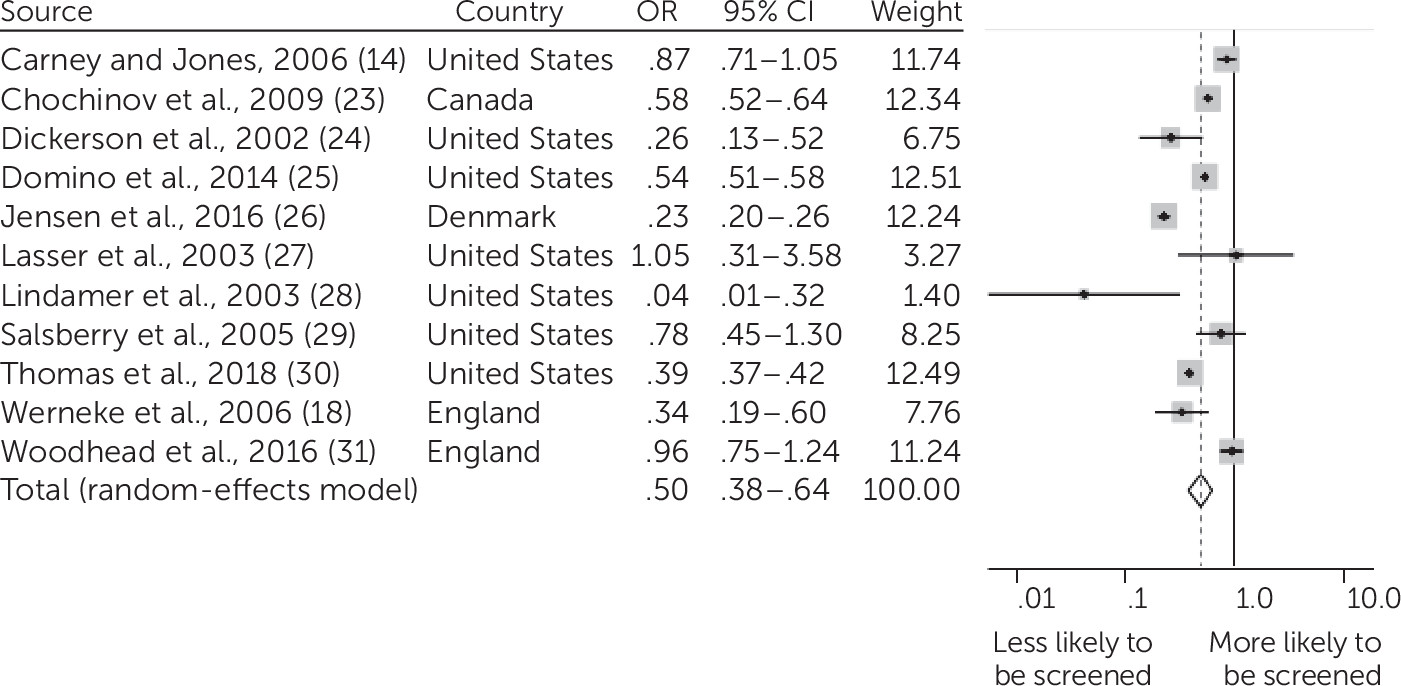

In 2014, Mitchell and colleagues (

12) conducted a meta-analysis examining breast cancer screening among women with mental distress or any mental illness and women without mental illness, finding that mammography screening rates were lower among women with mental illness. Upon further stratification of the sample with mental illness by diagnosis, they found that women defined as having serious mental illness were almost 50% less likely than women without mental illness to receive mammography. However, this study grouped multiple diagnoses under the category of serious mental illness, which may have masked some of the diversity and variation of presentation. For example, although the National Institute of Mental Health defines serious mental illness as a psychiatric disorder leading to severe functional impairment, the nature of symptoms and impairment in different psychiatric disorders—such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder—can vary widely. Notably, the type of mental illness appeared to affect breast cancer screening rates in some studies (

13,

14).

Because of this limitation, we chose to focus on breast cancer screening among women with diagnoses of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (e.g., schizoaffective disorder), given robust evidence that this group is more likely to have severe functional impairment and may face additional challenges in accessing care because of cognitive impairment related to psychiatric symptoms (

13). In addition, some studies have found that women with schizophrenia face greater stigma (

15), are less likely to attend primary care visits (

16,

17), and may have more difficulty communicating with unfamiliar providers (

18) compared with women without schizophrenia. These contributing factors could make it particularly burdensome for these individuals to obtain access to the health care system and health education and arrange mammography screening.

This article aims to summarize the literature to date on mammography screening rates and focus on disparities in care for women with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to distinguish mammography screening rates for this specific population, quantifying the degree of disparity by a meta-analysis.

Discussion

Women with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders were about half as likely to be screened for breast cancer as the general population. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to focus specifically on mammography screening rates for women with psychotic disorders. This study extends findings from previous reviews to highlight a disparity across four countries, in privately and publicly insured populations, at academic research centers and community clinics, and in inpatient and outpatient populations. Our review included nearly twice as many publications as a previous review on mammography screening for women with mental illness (

12), enabling us to evaluate breast cancer screening provision for over 25,000 women with diagnoses of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

There were a number of limitations of our study. First, all studies came from Western countries, primarily the United States, so findings may not be generalizable to other countries. However, four countries were included, reflecting screening rates in a Nordic country, in the Canadian and U.K. national health systems, and in private and public systems in the United States. Second, criteria for mammography screening varied across countries as well as across time, with the USPSTF recommending in 2009 that only women between the ages of 50 and 75 receive routine screening, a change from the earlier recommendation of routine screening for all women. However, the change in guidelines would not be expected to affect disparities in screening in our analyses, given that the comparisons were between women who were all receiving care under the guidelines in effect during that period. Third, there was considerable heterogeneity between studies. One reason for this may be that we could not determine severity of illness based on diagnosis. That is important, given that severity of mental illness, not a specific diagnosis, may be the more important factor in accessing preventive care services (

14). Fourth, it is possible that low mammography screening rates among individuals with schizophrenia are driven by other factors, such as socioeconomic status, race-ethnicity, or access to primary care, although we used adjusted odds ratios when possible, and multiple studies attempted to control for demographic factors and comorbid illnesses. Despite these limitations, we found a strong summary result indicating that women with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders receive mammography screening at lower rates than the general population. The result is consistent with prior studies showing lower rates of preventive health services for individuals with serious mental illness (

32–

34).

Lasser et al. (

27) conducted the only study that found higher rates of mammography screening among women with psychosis compared with a control population, but theirs was also the smallest of the included studies, with only 12 women with a diagnosis of psychosis. It is possible that there was selection bias in the participants in this study, such that they were more engaged in health care services than other patients with similar diagnoses.

Lower screening rates could explain why women with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses are found to have more advanced breast cancer at time of diagnosis (

11). In addition, poor screening is concerning in light of evidence from a recent literature review that women with schizophrenia have higher incidence of breast cancer and higher mortality rates due to breast cancer compared with the general population (

35,

36). It is important to note that these studies of cancer incidence and mortality have considerable heterogeneity, however, and it can be difficult to account for confounding socioeconomic factors.

Some barriers to adequate screening may apply to populations with and without mental illness. Having a regular primary care provider appears to promote preventive care such as cancer screening in the general population, and utilization of primary care services increases mammography screening rates among women with serious mental illness (

37,

38). Other studies of mammography utilization in the general population found lower probability of mammography screening receipt in areas affected by poverty and racial-ethnic segregation (

39). Other barriers to cancer screening in the general population include lack of test awareness, fear of the procedure, poor communication about prevention and prognosis, and limited financial resources (

40,

41).

However, individuals with serious mental illness may also face additional challenges in accessing appropriate cancer screening. In a survey of participants with psychiatric disorders at a community-based wellness center, the main barrier to mammography screening was not a lack of access to a primary care provider or to the screening procedure itself. Instead, the main barrier was that physicians did not suggest cancer screening to patients and failed to communicate the importance of screening (

42). With time constraints, primary care providers and psychiatrists may not prioritize cancer screening for patients with serious mental illness. Rather, they may focus on monitoring of metabolic disorders, which are increasingly recognized as a side effect of psychotropic medications and a driver of early morbidity in this population (

43). The increased focus on addressing psychiatric symptoms may lead to deferring routine preventive screening discussion for future visits, but the future discussion never occurs. Some providers might defer screening because they believe that individuals with serious mental illness will have difficulties following through with treatment such as radiation and chemotherapy (

17).

Given that patients with serious mental illness may need more in-depth communication and guidance to follow up with cancer screening procedures, such as mammography and colonoscopy, creative models are needed for emphasizing the importance of preventive care for individuals with serious mental illness. As an inverse of the collaborative care model, a care manager, social worker, or nurse may be able to play a critical role in connecting these patients with necessary cancer screening services in specialty mental health settings (

44,

45). As a recent Cochrane review indicates, an evidence-based intervention for increasing cancer screening rates for people with severe mental illness has yet to be identified (

46). Clinical trials are underway to test new strategies integrating mental health and cancer treatment for the population with serious mental illness, but initial screening remains a barrier to timely and appropriate intervention (

47).

Prior studies have found disparities in breast cancer screening rates on the basis of race-ethnicity and income, with results indicating that low-income women and women from racial-ethnic minority groups are less likely to receive screening consistent with guidelines. Our finding that women with schizophrenia and psychosis were about half as likely to be screened as the general population supports the argument that persons with severe mental illness should be designated as a health disparity population, with special funding to target disparities in care (

48,

49). Future studies are needed to determine whether women who have schizophrenia experience further differences in mammography screening rates on the basis of race or ethnicity.