Use of Tele–Mental Health in Conjunction With In-Person Care: A Qualitative Exploration of Implementation Models

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

HIGHLIGHTS

Methods

Study Participants and Sampling Strategy

Interviews

Analysis

Results

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

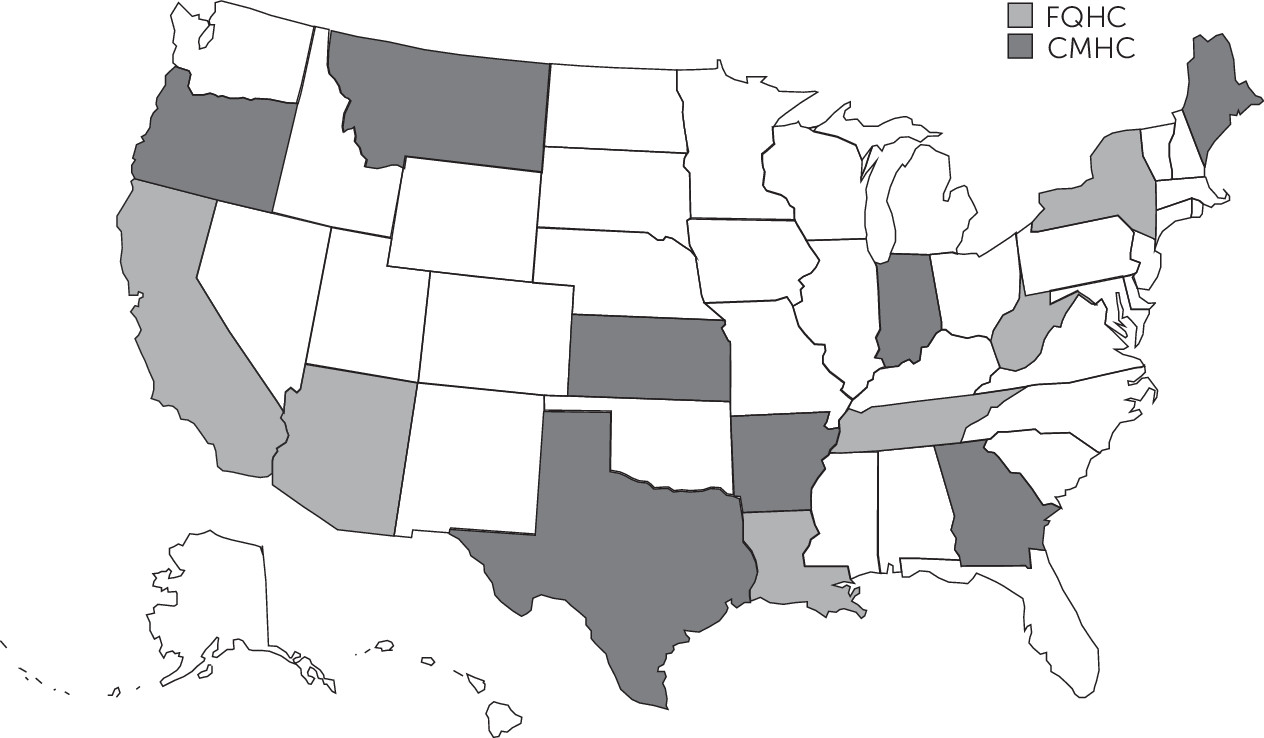

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 3 | 15 |

| West | 7 | 35 |

| South | 8 | 40 |

| Midwest | 2 | 10 |

| N of clinic sites | ||

| 2–5 | 7 | 35 |

| 7–10 | 10 | 50 |

| ≥11 | 3 | 15 |

| Location of clinic sites | ||

| Rural only | 13 | 65 |

| Urban only | 1 | 5 |

| Mix of rural and urban | 6 | 30 |

| Percentage of patients with Medicaid | ||

| ≤50 | 8 | 40 |

| 51–69 | 8 | 40 |

| ≥70 | 4 | 20 |

How Tele–mental Health Is Used

Services for health center patients.

| State and facility type | Telepsychiatry | Therapy via telehealth | Other telehealth services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | |||

| CMHC | PNP employed by health center (but located out of state) provides medication management | LCSWs employed by health center (who also see patients in person) conduct therapy at understaffed clinic locations | Substance use disorder services by PNP |

| CMHC | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for PNP for medication management | None | None |

| Arkansas | |||

| CMHC | Contracts with independent child psychiatrist for medication management, initial psychiatric evaluations, and update evaluations | None | None |

| California | |||

| FQHC | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for psychiatrists for medication management | LCSWs employed by health center (who also see patients in-person) conduct therapy at understaffed clinic locations | None |

| FQHC | Psychiatrists employed by health center provide medication management to understaffed clinic sites | None | None |

| Georgia | |||

| CMHC | Contracts with a telemedicine vendor for medication management by PNPs | None | None |

| Indiana | |||

| CMHC | Contracts with independent psychiatrist and PNP for medication management; PNP employed by health center (who also sees patients in person) is available on an emergency basis for understaffed clinic sites | None | Substance use disorder services by PNP and psychiatrist |

| Kansas | |||

| CMHC | Contracts with a telemedicine vendor for child psychiatrist and midlevel general provider; psychiatrist employed by health center. All provide medication management | Staff employed by health center conduct therapy (small program in case-by-case basis) | None |

| Louisiana | |||

| FQHC | Contracts with academic medical center for second opinion by child and adult psychiatrists on complex cases and uses PNP employed by health center (who also sees patients in person) for medication management | None | None |

| Maine | |||

| CMHC | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for medication management by psychiatrists | LCSWs employed by health center conduct therapy with Medicare patients; group therapy for sexual assault program conducted by staff employed by health center | None |

| Montana | |||

| CMHC | PNPs employed by health center (who also see patients in person) provide medication management to understaffed clinic sites | LCSWs employed by health center conduct therapy with Medicare patients | None |

| New York | |||

| FQHC | Contracts with independent psychiatrist for medication management | None | None |

| FQHC | Contracts with adult and child psychiatrists and neurologists at academic medical center and another FQHC (all within their in-person referral networks) for medication management | Contracts with staff member at another FQHC for bilingual counseling services; LMHCs and LCSWs employed by health center conduct therapy | Substance use disorder services by primary care providers and peer counselors after an initial in-person visit |

| Oregon | |||

| CMHC | Contracts with a telemedicine vendor for medication management by PNP and child psychiatrist | None | None |

| CMHC | Contracts with telemedicine vendor and uses own (off site) staff psychiatrists and PNPs for medication management and psychiatric screening | Staff employed by health center conduct individual therapy, family therapy, and peer counseling | Offers substance use disorder services by psychiatrists and NPs to complement in-person substance use disorder treatment. Patients in school-based clinic receive counseling and prescribing services via video |

| Tennessee | |||

| FQHC | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for medication management by child psychiatrist | None | Substance use disorder services with LCSW |

| Texas | |||

| CMHC | PNPs and psychiatrists employed by health center (who also see patients in person) provide medication management to understaffed clinic sites | Staff employed by health center conduct therapy (small program in case-by-case basis) | Intakes at all understaffed rural sites conducted via video by LPCs or LCSWs employed by health center; crisis-service coverage for 48-hour extended observation |

| CMHC | Contracts with health center cooperative for psychiatrists and uses own staff for intakes and medication management | None | Psychiatrists employed by health center provide crisis assessments to facilities in their network |

| CMHC | Contracts with telemedicine vendor for double-boarded psychiatrists and uses own staff PNPs and psychiatrists (some who also see patients in person and others who are exclusively telehealth providers) | Multiple types of providers conduct cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, rehabilitation skills training, and group therapy | None |

| West Virginia | |||

| FQHC | Contracts with independent psychiatrist (former employee) for medication management | Contracts with independent LCSW (former employee) for individual and group therapy | Substance use disorder services with LCSW |

Services at community sites.

Tele–mental health and in-person care.

Goals and Benefits of Tele–mental Health

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| By offering tele–mental health, health centers can introduce a care model that can be reimbursed | “We [CMHC in Maine] added therapy with LCSWs to our existing tele–mental health services because although several types of licensed providers were providing in-person therapy here, psychotherapy services by providers other than LCSWs and psychologists were not reimbursed by Medicare. Providing therapy through telehealth allowed Medicare patients at any location in our network to receive billable services even if their specific clinic location did not have in-person LCSWs.” |

| Patient engagement is better when tele–mental health is combined with in-person touchpoints | “It's a mix. Yeah. Nobody's receiving everything [via telehealth]. . . . I don't know that this is valid, statistically, or have any kind of data, I haven't seen anything, but it's engagement. I mean, you need to look the guy in the eyes and have a conversation with him. It's not the same via video.” |

| Teletherapy is not equivalent to in-person therapy with respect to quality | “But, I think it’s [therapy with telehealth] different than telepsychiatry and that I think you would lose more, because therapy is relationship-based, and that making that connection, I think that's harder to do over a screen versus asking face to face, ‘How are your medications working… how is your sleep?’ ” |

| Confidentiality and safety concerns prevent some health centers from offering tele–mental health in patients’ homes | “[Tele-mental health in the home] was something that we discussed and that decision was based on the lack of confidentiality at the patient's home. For instance, we have problems with domestic violence. We didn't feel like it was a good idea to encourage patients to have a conversation with a therapist where they open up about everything, including the people in their lives, and leave their confidentiality up to them, when they might not even understand the risk.” |

| Patients feel less connected to tele–mental providers because of limitations of a video encounter | “It seems to be very difficult for the prescriber to pick up on humor when somebody is trying to be funny about something, so there tends to be miscommunication.; “When we move telepsychiatry into a clinic, we see our no-show rates increasing. So the people who vote by filling out the [patient satisfaction] survey are fine with it, but the people who vote with their feet are not coming in for visits.” |

| Tele–mental health hampers information sharing among members of the care team | “Building a team around services when one of the key providers is not co-located is a challenge. . . . Just in terms of sharing information . . . like in one site we have somebody go to the state hospital and then later get discharged and re-enter services, and nobody had told the nurse practitioner [who provides medication management via telehealth].” |

| Patients are given the option to see a provider in person or via telemedicine. | “Whatever the patient wants. We always offer it, so if a patient looks at us like we're nuts when we say, ‘Hey do you want to see your counselor by video?’ And if they say, ‘No, I'm not interested,’ well then that ends that discussion. We're very up front with patients and say, ‘We use telehealth to provide you more access. You have more options if you're willing to use the program with telehealth.’ ” |

Reasons for Not Offering Specific Tele–mental Health Services

Drawbacks of Implemented Models Of Tele–mental Health

Decision to Offer Tele–mental Health Rather Than In-person Services

Future Plans for Tele–mental Health

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 20.67 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).