Access to mental health care for inmates is a worldwide problem (

1–

4), but the situation in French prisons has recently been in the spotlight (

5–

8). With more than 70,000 people detained under severely overcrowded conditions (including 21,000 in pretrial detention), the situation of prisons in France is extremely concerning, and high levels of psychiatric morbidity have been reported among French prisoners (

9–

13). In a landmark study, Falissard et al. (

11) showed that 36% of inmates had at least one severe psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia (3.8%) or major depressive disorder (17.9%).

The mental health care system for inmates in France, created in 1985, includes three levels of care that are affiliated with the public health system (

14). These levels are the same for all prisoners, regardless of whether they are incarcerated in a jail or prison. The first level, composed of consultation and ambulatory care units, is present in each of the 188 French correctional facilities. Only 26 of the correctional facilities (14%) benefit from the second level of care,

services médico-psychologiques régionaux (SMPRs; “regional medical-psychological services”). SMPRs include a team of psychiatrists, nurses, and psychologists (often better staffed than ambulatory care units) as well as day hospital beds inside the prison. (Cells are not accessible to health workers at night.) The psychiatrist working in prison can refer a patient to the SMPR, where care is provided only with the consent of patients.

The third level, which manages full-time psychiatric hospitalizations for inmates, has undergone the most significant evolution in the past few years. Until recent changes in the law, only involuntary full-time psychiatric hospitalization was possible for inmates (

15,

16). Hospitalization occurred in general psychiatric hospitals and without mandatory police custody, but this arrangement was associated with several issues, particularly the inappropriate use of isolation and mechanical restraint. In this context, a law provided for the creation of new facilities called

unités hospitalières spécialement aménagées (UHSAs; “specially equipped hospital units”) (

17). The nine UHSAs created in France (with a total capacity of 440 beds) are full-time inpatient psychiatric wards exclusively for inmates (

8). They are affiliated with the public health system, but the prison administration ensures the security of the institution, manages entry and exit, coordinates the transfer of patients, and resolves exceptional security problems. In contrast to general psychiatric hospitals, where detainees can be hospitalized only involuntarily, voluntary and involuntary hospitalizations are possible in UHSAs. Both types of hospitalization are requested by the psychiatrist working in a prison. Written consent of the patient is required for voluntary hospitalization, whereas a medical certificate attesting that the patient suffers from a mental illness and is “a danger to himself or others” is needed for involuntary hospitalization (with a systematic control of each measure by the liberty and custody judge who can order the lifting of invalid hospitalizations).

Unités pour malades difficiles (UMDs; “units for difficult patients”), maximum security wards, complete the third level of care (10 UMDs, 620 beds for men, 36 beds for women). Fully managed by the public health system, UMDs are designed to accommodate patients, detained or not, who “present such a danger to others that the necessary care, supervision and safety measures can only be carried out in a specific unit.”

Since the first UHSA was built in 2010 in Lyon, no study has examined the activity of the UHSAs nor their impact on the proportion of inmates hospitalized in community psychiatric hospitals. For this study, we used national data from 2016 to describe the overall patterns of psychiatric hospitalization (levels 2 and 3) of detained people in France.

Methods

Database

The study was conducted by using the national psychiatric hospital discharge database called recueil d’informations médicalisé en psychiatrie (RIM-P; “medical information collection in psychiatry”). All admissions, including inpatient and day hospital care in every public or private psychiatric hospital in France, have been collected anonymously in the RIM-P database since 2007. A unique national identification number for each patient allows all admissions for a patient to be linked. The database includes individual-level data about the date of admission, length of stay, hospital code number, sector code, and outcome (i.e., discharge, hospital transfer, death). Social demographic characteristics include gender, age, and place of residence. One principal diagnosis, defined as the main reason for admission and in accordance with ICD-10, is recorded.

Of the three levels in the organization of services for prisoners’ mental health care, only levels 2 (day hospitalization in SMPRs) and 3 (full-time hospitalization in general psychiatric hospitals, UHSAs, or UMDs) are included in this study. In 2016, only eight UHSAs (380 beds) were operational. Unlike SMPRs and UHSAs, which can accommodate only incarcerated patients, UMDs and general psychiatric hospitals can accommodate both incarcerated and nonincarcerated patients. For this study, we included data only from incarcerated patients. No data about nonincarcerated patients hospitalized in general psychiatric hospitals or in UMDs are presented.

Cases were identified in the national RIM-P database through the following criteria: hospital code number corresponding to UHSA, UMD, or SMPR; the specific legal mode used for the hospitalization of inmates (i.e., D398); the specific sector code used for psychiatric facilities in prison (i.e., P). From January 1 to December 31, 2016, data were extracted for 4,392 patients.

Ethical approval for this study was not needed because we had access to an anonymous administrative database. Moreover, Santé Publique France, the national French public health agency, is legally allowed full access to the national hospital discharge databases for surveillance purposes (

18).

Analysis

The length of stay for each hospitalization was calculated as the date of admission until either the date of discharge or December 31, 2016, if the patient was still hospitalized. The cumulative length of stay was the sum of different lengths of stay for the same patient. Medians, first quartiles (Q1), third quartiles (Q3), means, and standard errors were estimated for quantitative variables, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were established using the standard errors.

For each stay, the ICD-10-coded principal diagnosis was collected; thus, for patients with multiple stays during the year, several primary diagnoses were possible. As a result, patients with multiple stays and diverging primary diagnoses were counted more than once for the analysis of diagnoses. For each stay, the legal mode of hospitalization (voluntary, involuntary, or both) was noted.

To describe the impact of UHSAs on the full-time psychiatric hospitalizations of detained people, we also calculated the percentage of these hospitalizations in UHSAs (i.e., number of hospitalizations in UHSAs divided by the total number of full-time psychiatric hospitalizations among inmates) for each geographical area, or “department,” in France. For these analyses, only the departments with more than five hospitalizations from prisons located in the area (i.e., 81 of the 96 French departments) were considered. Analyses were performed and maps were created with SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1.

Results

In 2016, 4,392 of 66,678 (6.6%) people incarcerated in France were hospitalized (92% males, N=4,050). The mean age was 34.3 years (95% CI=34.0–34.7).

Number of Psychiatric Hospitalizations

The 4,392 incarcerated patients had 7,027 admissions, including 5,121 full-time hospitalizations and 1,906 day hospitalizations. Patients experienced 2,631 hospitalizations in UHSAs, 2,391 in general psychiatric hospitals (excluding UMDs), 99 in UMDs, and 1,906 in SMPRs.

Two-thirds of the patients (N=2,968, 68%) were hospitalized once during the year, 839 patients (19%) had two admissions, 300 patients (7%) had three, 144 patients (3%) had four, and 141 patients (3%) had five or more.

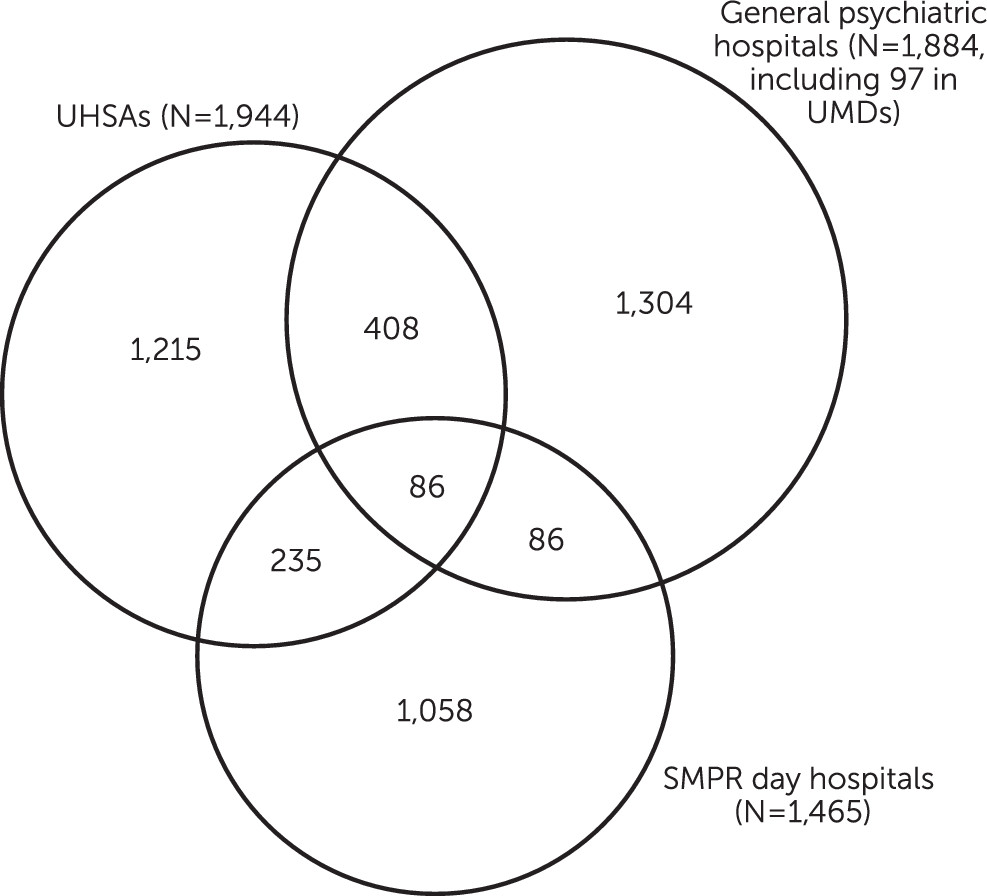

Figure 1 shows the distribution of patients in the different psychiatric facilities. (The principal diagnoses noted for all detainees according to the facility involved are presented in an

online supplement.)

Length of Stay

The mean length of stay was 59 days (95% CI=55–63, median=19 days, range 1–7,892 days, Q1=7 days, Q3=47 days). However, 158 stays lasted more than 1 year. Although most patients (N=3,714, 85%) were admitted in 2016, 32 patients were admitted before 2014 (20 were admitted in 2013, seven in 2012, two in 2011, one in 2009, one in 2007, and one in 1995).

The mean length of stay differed significantly with the type of facility. Inpatient hospitalizations in UMDs were the longest, with a mean stay of 371 days (95% CI=190–551, median=115 days, Q1=35 days, Q3=341 days). Day hospital stays in SMPRs were the second longest, with a mean stay of 102 days (95% CI=94–110, median=38.5 days, Q1=15 days, Q3=104 days). For other inpatient hospitalizations, stays were longer in UHSAs (mean=46 days, 95% CI=43–50, median=26 days, Q1=13 days, Q3=49 days) than in general psychiatric hospitals (excluding UMDs) (mean=25 days, 95% CI=20–29, median=7 days, Q1=3 days, Q3=15 days). The median cumulative length of stay per patient was 27 days (95% CI=80.1–93.3, mean=86.7 days).

Characteristics of Admissions to UHSAs

A total of 1,944 patients were admitted to the UHSAs (2,631 stays). Seventy-eight percent of the patients (N=1,514) had only one hospitalization in a UHSA during the year, 312 patients (16%) had two hospitalizations, and 118 patients (6%) had three or more.

Of the 1,944 patients admitted to UHSAs, 320 (17%) were transferred from other facilities; most (N=255) were transferred from general psychiatric hospitals, although some patients (N=65) were transferred from SMPRs. Upon discharge from the UHSA, 27 patients were transferred to a UMD.

Of the 2,631 stays in the UHSAs, 56% (N=1,437) were for patients who came from prisons situated in the same geographical area (department) as the UHSAs. In the departments where a UHSA was implemented at the time of the study, 92% (N=1,437 of 1,566) of the hospitalizations took place in UHSAs. In the departments where no UHSA was implemented (N=73), only 33% (N=1,116 of 3,393) of the hospitalizations took place in UHSAs. Data were missing for 78 hospitalizations. (A map showing the location of the eight UHSAs and the percentage of hospitalizations in UHSAs for each French department is available in the online supplement.)

Legal Modes of Hospitalization

Depending on the type of facility where the patient was admitted, voluntary hospitalization, involuntary hospitalization, or both may have occurred during the year for the same patient. Patients and stays per modality of hospitalization are presented in

Table 1. In 2016, 48% (N=939) of the patients admitted to UHSAs were hospitalized only on a voluntary basis, 26% (N=495) only on an involuntary basis, and another 26% (N=510) on both voluntary and involuntary bases. Admission to a UHSA was voluntary in 60% of the stays (N=1,585), and during hospitalization in the UHSA, the legal mode of hospitalization changed from involuntary to voluntary in 21% of stays (N=549).

Discussion

In this article, we present the first study about utilization of hospital-level mental health care services for inmates in France. Because major changes occurred in the French prison health system, particularly with regard to psychiatric hospitalization for inmates with the creation of UHSAs in 2010, we focused on day and full-time hospitalization. On the basis of data from the national psychiatric hospital discharge database, we showed that 4,392 of the 66,678 people incarcerated in France (66 per 1,000), mostly young men, were hospitalized in psychiatric wards in 2016. In comparison, 417,000 nonincarcerated people were hospitalized in psychiatric wards in France during 2016 (324,000 full-time hospitalizations, including 80,000 involuntary hospitalizations), a rate of 6 per 1,000 residents (

19). In our sample, almost one-third of patients (N=1,424) were hospitalized several times during that year, and 19% (N=815) of patients were admitted to at least two different facilities (UHSA, general psychiatric hospital, UMD, or SMPR). A significant proportion of patients also required particularly long hospital stays. We identified psychotic disorder as the primary diagnosis for 31% (N=1,373) of the patients hospitalized (see

online supplement), a prevalence that is particularly concerning.

The most important result from this study is that despite the creation of UHSAs, the hospitalization of inmates in general psychiatric hospitals remains frequent in France (2,391 admissions in 2016, which correspond to 47% of the 5,121 full-time psychiatric hospitalizations among inmates). Two main explanations can be proposed. First, the capacity of the UHSAs (440 beds, 380 at the time of the study) is probably too low to meet the need for hospitalization. The number of people incarcerated has been steadily increasing in France over the past 20 years, from 51,903 in 2000 to 71,828 on April 1, 2019. Epidemiological studies have noted that 36% of inmates have at least one psychiatric illness considered marked to severe (

11); thus, one could hypothesize that the 440-bed capacity (380 at the time of the study) is insufficient. Consequently, the UHSAs are rapidly saturated, and hospitalization of inmates in the civil system remains the only possibility for full-time psychiatric care. The low number of detained patients hospitalized in UMDs (N=97) should also be noted.

Second, the distance between the UHSAs and certain prisons is considerable (up to 300 km), which may make an emergency hospitalization in a UHSA impossible and consequently require a hospitalization in the local general psychiatric facility. Human resources are limited, and the transfer of a detained person from a prison to a UHSA requires significant logistics, including a team of caregivers accompanied by a prison escort.

As mentioned above, the hospitalization of inmates in the civil system is associated with several issues. In particular, the use of unsuitable premises with a high risk of escape sometimes leads to the use of isolation and mechanical restraint even when they are not clinically justified (

6,

20). Although no conclusion on the quality of care in each type of facility can be drawn from this study, the differences observed in lengths of stay may reflect the difficulty of providing optimal psychiatric care to inmates in general psychiatric hospitals. Indeed, the median stay was 26 days in UHSAs compared with 7 days in general psychiatric hospitals, whereas no major difference was shown in the diagnoses of patients between the different facilities (see

online supplement). One could hypothesize that inappropriate conditions for the full-time hospitalization of inmates in general psychiatric hospitals lead psychiatrists to shorten the duration of stay in these institutions. Interestingly, a recent patient satisfaction survey conducted in two UHSAs showed that patients who had been hospitalized in both general psychiatric hospitals with prisoner status and in UHSAs indicated a preference for and satisfaction with hospitalization in the UHSAs (

21).

The high proportion of patients with voluntary psychiatric hospitalizations is also worth noting. Almost half of the 7,000 stays analyzed in our study were voluntary, which appears to be an encouraging finding given the difficulties often highlighted in caring for incarcerated individuals. Engaging patients who are incarcerated and creating an environment that facilitates the growth of working alliances and enhances motivation for treatment are challenging tasks (

22,

23). Although considerable effort is being devoted to researching and practicing prison psychiatry, incarceration remains an adverse and often antitherapeutic condition (

24,

25).

Since 1985, SMPRs have been able to accommodate patients in voluntary day hospitalizations. Since 2010, UHSAs have offered prisoners the possibility of voluntary admission for full-time psychiatric hospitalization. Even if some inmates might be attempting to gain respite from prison without an underlying condition, we believe the high proportion of voluntary admission (60% in our study) highlights a major breakthrough in access to psychiatric care for inmates in France, in accordance with the principle of equivalent treatment for prisoners (i.e., equal standards of treatment inside and outside prison).

One of the main limitations of this study was that we analyzed data for only 1 year. These results should therefore be replicated over several years or complemented by a longitudinal study to show how bed utilization has changed with the construction of UHSAs. Second, since we did not have access to the RIM-P database for 2017, the method we used to calculate length of stay artificially shortened the duration of stays of those patients who stayed beyond December 31, 2016. On December 31, 623 patients (9% of overall stays) were still hospitalized (161 in UHSAs, 105 in general psychiatric hospitals, 43 in maximum-security units, and 314 in day hospitals). Third, no information about the penal situation (criminal history, severity of index offence) of the patients was available in this study.

Conclusions

This article is the first to present data about utilization of hospital-level mental health care services for inmates in France. We showed that 4,392 incarcerated people were hospitalized in 2016, with a high proportion of these hospitalizations in general psychiatric hospitals, despite the recent creation of UHSAs, new full-time inpatient psychiatric wards. The system of hospital-level psychiatric care for prisoners in France will therefore need to evolve in the coming years, and future studies are needed to investigate the quality of treatment in UHSAs to determine the benefit of further developing these facilities in France.