Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often incur high health care expenditures. U.S. children ages 5–10 with employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) who had ASD recorded as a diagnosis during 2003 had mean expenditures six times higher ($6,420 versus $920) than those incurred by children who had no ASD diagnosis codes; median expenditures were 11 times higher ($3,020 versus $260) (

1). However, little is known about recent changes in expenditures for insured children with ASD and the impact of increased access to outpatient behavioral intervention–related services for ASD on overall health care spending.

Over the past decade, there has been increased recognition that many children with ASD can benefit from intensive (>15 hours per week) behavioral and developmental interventions, including those based on applied behavioral analysis (ABA) principles (

2–

6). Policy changes, including state insurance mandates (

7,

8), the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (

9), and actions by the Office of Personnel Management in 2012 to allow and in 2017 to require Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) plans to cover services (

10), have sought to promote access to services for individuals with ASD. Mandates have increased spending for children with ASD, especially those ages 3–7, who were enrolled in health plans subject to the mandates (

8,

11–

13).

Intensive behavioral and developmental interventions for ASD are typically targeted to preschool-age children, with evidence of benefits associated with receipt of services for 25–40 hours per week (

4,

6). However, only a minority of eligible children receive such services, which can exceed $50,000 in costs per year per child (

5,

14–

16). Our objective was to assess changes during 2011–2017 in spending among children ages 3–7 with current-year ASD diagnoses who were enrolled in self-insured ESI health plans, compared with spending for other children. We also examined changes in the percentages of children who met specified cutoffs for frequency or intensity of use of behavioral intervention–related services.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document post-2012 changes in health care spending for U.S. children with ASD covered by large-employer–sponsored plans. Increases in inflation-adjusted per-child expenditures for children ages 3–7 with current-year ASD diagnoses far outpaced spending for children without ASD, as defined in the study; during 2011–2017, the increases were 51% and 8%, respectively. Mean spending per child with current-year ASD increased from roughly $13,000 in 2011 to $20,000 in 2017. Combined with the doubling of current-year ASD diagnoses, two-fifths (41%) of the total increase in per-child spending for all children ages 3–7 in noncapitated large-employer–sponsored plans was accounted for by spending on children with current-year ASD diagnoses.

Despite rapid growth in the prevalence of current-year ASD diagnosis to 1.05% in 2017, it remained low relative to the 1.85% prevalence among 8-year-old children in the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network in 2016 or the 2.76% parent-reported prevalence among children ages 3–17 in the National Health Interview Survey in 2016 (

21,

22). It should be noted that use of a time window of 5 years resulted in twice as many children being classified as having ASD in 2013, 1.45% versus 0.67% (see Table S9 in

online supplement). Additionally, children with parent-reported ASD may not have ASD listed in medical claims and may also be more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid.

The increase in spending for privately insured children ages 3–7 with current-year ASD was driven by outpatient behavioral intervention–related spending, which accounted for almost all of the nearly fourfold increase in inflation-adjusted spending per child with ASD, compared with a 2% increase in all other spending. In 2011, 2.5% of children with current-year ASD incurred more than $20,000 in outpatient spending (in 2017 dollars) associated with behavioral intervention–related codes, which increased to 14.4% in 2017 (

Table 3). Because early intensive behavioral and developmental interventions are likely to cost at least $20,000 per year (

5), it follows that a minority of privately insured children with ASD were receiving early intensive interventions reimbursed through health plans. One cannot determine by using claims data which children with ASD required early intensive intervention. Although cost offsets have been documented with early intensive interventions (

5,

14,

15), the impact of services delivered with lower intensity or frequency is not known.

The expansion in spending by large-employer–sponsored plans on behavioral services for young children with ASD cannot be explained by state mandates, because few such plans were subject to state laws, unlike fully insured ESI plans (

8,

11). On the other hand, the expansion of mandates from 2008 onward (

7) together with grassroots advocacy from parents may have contributed to growing acceptance by self-insured employers of early intensive behavioral intervention as the standard of care, as reflected in national FEHB policies that evolved from allowing such services in 2012 to a mandate for such services in 2017 (

10).

Our findings cannot be generalized to children with public insurance or no health insurance. Published estimates of health care costs for U.S. children with ASD for all payer types are substantially lower than those reported here (

23–

25). Traditionally, Medicaid programs have been reported to pay for behavioral therapies for Medicaid-enrolled children with ASD (

26–

31).

An important limitation is that the MarketScan Commercial databases include only claims submitted to participating ESI plans; claims covered by Medicaid are not included. Children with ASD whose families have private insurance may obtain Medicaid coverage through waiver programs (

28,

30,

32,

33), “medically needy” classification, receipt of Supplemental Security Income benefits, or conventional income-based eligibility. We were unable to quantify the extent to which the estimates for the ESI sample might have been underestimated and how that changed over time. This could be an area for research using state all-payer claims databases.

Our study had other limitations. We had no information on income, education, or race-ethnicity. All administrative databases are subject to incomplete sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis codes for ASD (

20). Requiring two or more claims with ASD diagnosis codes increased the specificity but lowered the sensitivity for identifying children with ASD (

20). The length of the “window” of claims data used to identify ASD cases affected estimates of both numbers of ASD cases and per-child spending for those meeting the ASD case definition. In supplementary analyses, we altered the time window over which ASD case status was ascertained. We found that requiring two or more claims with ASD codes for current-year ASD excluded roughly half the children who met the same ASD claims criterion using 5 years of data (see Table S6 in

online supplement). The excluded children had considerably lower expenditures in years prior to meeting the ASD claims criterion. However, those children accounted for a very small proportion of the comparison group. We were able to compare only temporal changes for a few years for the group ascertained with 5 years of data and observed similar increases in expenditures despite lower levels of per-child spending with a longer window for case ascertainment (see Table S9 in

online supplement).

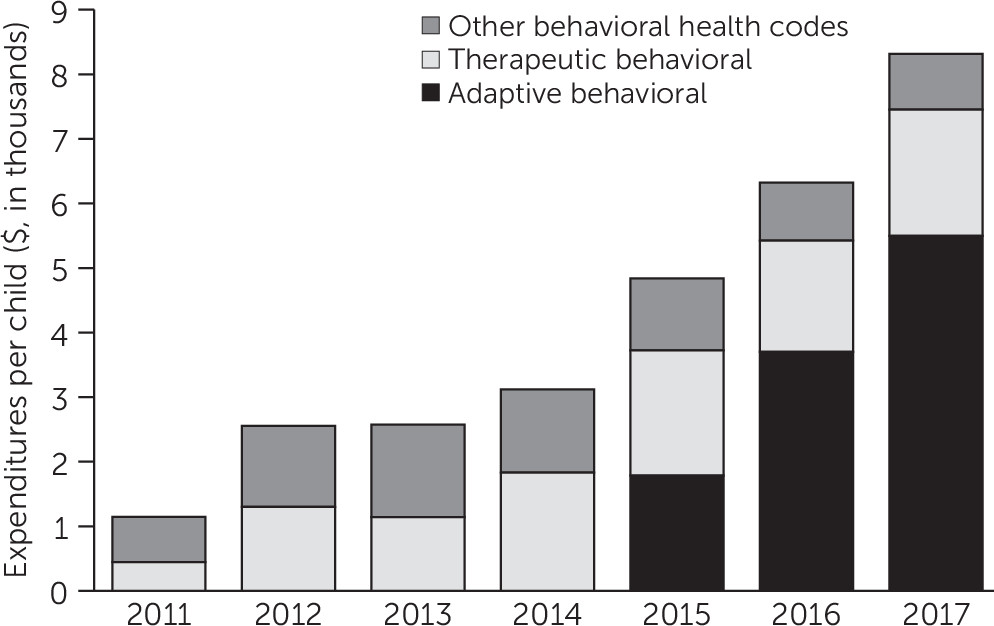

Procedure codes for ABA services were introduced in late 2014 and soon dominated behavioral intervention–related spending. It is likely that the introduction of specific ABA procedure codes increased reimbursements as well as substituted for other procedure codes, specifically for therapeutic behavioral services. The share of all behavioral intervention–related spending associated with those two types of procedure codes increased from 24% in 2011 to 90% in 2017 (

Figure 1). Because most other behavioral intervention–related procedure codes do not specify the type of service provided, we could not determine which other claims may have been billed for intensive behavioral and developmental interventions.

In addition, our study did not assess the overall utilization of services by privately insured young children with ASD, and it excluded services delivered through schools or paid directly by families or through Medicaid waivers. Surveys of U.S. caregivers of school-age children with ASD reported that schools have been the primary place where behavioral services are delivered (

34,

35). Other data sources would be required to determine to what extent increased spending by large-employer plans represented increased use of interventions among privately insured children with ASD in this age group, as opposed to substitution of payment for services otherwise paid for by families, schools, or Medicaid.

Changes in the composition of the MarketScan sample over time could affect comparability of estimates. We restricted our main analysis to noncapitated large-employer plans, which had more stable enrollments than did other plans (see Table S1 in online supplement). Likely owing to changing plan composition, expenditure estimates for children with ASD in the other two plan types were less stable and more difficult to interpret (see Tables S5 and S6 in online supplement). Finally, our database included only year of birth; we were unable to accurately determine a child’s age when he or she received services.