Schizophrenia is considered the most severe psychiatric disorder, from both a clinical and a research point of view (

1,

2). In contrast, cluster B personality disorders (e.g., narcissistic, borderline, histrionic, and antisocial disorders) are not always considered severe mental illnesses (

3). This difference might explain the asymmetric attention these personality disorders have received by researchers and clinicians. This asymmetry is reflected in the number of published research studies: 3,127 studies for schizophrenia versus 613 for personality disorders (

4). Similar patterns can be seen for the medications approved for treatment of these mental illnesses (

5). Furthermore, in Quebec several evidence-based treatment models for schizophrenia, such as first-onset programs or assertive community treatment teams (

6), have largely been implemented, whereas similar models for treating people with personality disorders have only recently been proposed (

7).

The discrepancy in expenditures for research or treatment of these two disorders is not proportional to their respective prevalence. The prevalence of schizophrenia is around 0.7% (

8) and that of cluster B personality disorders about 3.3% (

9). In terms of excess mortality, schizophrenia has a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) of 2.6 (

8), and cluster B personality disorders have an SMR between 3.7 (female outpatients) and 10.8 (female inpatients) (

10). A recent Danish study of linked health administrative databases of their complete population reported a slightly higher SMR of 2.57 for schizophrenia and 2.26 for personality disorders, compared with the general population (

11). These observations indicate that people with schizophrenia and cluster B personality disorders experience a significant loss of life expectancy compared with the general population (

3,

12–

14). In addition to the established data showing reduced life expectancy, patients with cluster B personality disorders have general medical and psychiatric comorbid conditions that affect their quality of life and functional status (

15–

17). Finally, cluster B personality disorders are associated with high levels of mental health service use (

18–

21) and with elevated societal costs (

22). The societal costs for cluster B personality disorders and schizophrenia are similar in Europe, estimated at 40,441 euros (

23) and 43,561 euros (

24) per person per year, respectively.

As shown by the aforementioned Danish study (

11), which used national health administrative databases to compare causes of increased mortality rates, use of data from large population registers can provide a more complete picture of the differences and similarities between schizophrenia and personality disorders in terms of comorbid conditions and medical service use. In Canada, such a universal health plan is administered by each province as part of a national universal health system, offering free access to medical visits and hospitalizations (

25). The administrative databases for health surveillance and research are located in Quebec. The Quebec Integrated Chronic Disease Surveillance System (QICDSS) (

26) is a data source that can be used to study comorbid conditions and service use among individuals with cluster B personality disorders or schizophrenia. Here, we sought to compare the prevalence of general medical and psychiatric comorbid conditions and the use of health care services (including psychotherapy by physicians) among patients with cluster B personality disorders, schizophrenia, or both disorders, compared with prevalence and use in the general population.

Methods

Data Source and Population

Our method of data collection and analysis for cluster B personality disorders has been previously described (

12). Like other Canadian provinces, Quebec has a public managed care system for health and social services. More than 99% of nearly 8 million residents in Quebec are included in the QICDSS (

12). A quality study of the QICDSS (

13) showed that at least 95% of psychiatrists’ health care claims include a diagnosis, and nearly 90% of all claims include one diagnosis. Since 1996, the QICDSS (

26) links, by personal health insurance numbers, five databases: physician claims, hospitalization, registration, death registry, and public drug plan. Physicians’ claims for general health and psychiatric disorders were registered with

ICD-9 codes, whereas hospitalizations were registered with

ICD-10 codes that were released in 2006.

We conducted a population-based observational study of Quebec residents ages ≥14 years who were insured under the provincial health program (Régie d’assurance maladie du Québec) between April 1, 1996, and March 31, 2017. A initial period of 5 years (from April 1, 1996, to March 21, 2001), during which data were collected and not reported, was used to ensure stability of the system by that time. QICDSS databases contain open, dynamic, population, and administrative data that are collected prospectively.

The database used for this study was designed to meet administrative needs and might have had some flaws for research purposes. For example, the database is updated regularly, and slight differences in numbers for the groups analyzed appeared over time. Since figures and tables were not created from data collected at the same time, we note that very minor differences appeared in the sample sizes of the cohorts.

Cases and Variables

A group composed of four psychiatrists (L.C., P.D., E.V., A.L.) and one psychologist (Dr. Lise Laporte at the Department of Psychiatry, McGill University) working within the Quebec health care system with expertise in the treatment of personality disorders prepared the case definitions. (All of the experts worked in specialized programs across three different administrative networks.) The case definition was obtained via consensus after two multisite work sessions. The main objective for the selection was to obtain the most clinically relevant data. All selected

ICD-9 codes were clinical indicators included in or close to the construct of a cluster B personality disorder. In short, this procedure transformed an

ICD-9 diagnosis into a

DSM category. We included all

ICD diagnoses with code 301.9 (personality disorder unspecified) as part of cluster B because the expert group noted that this code is commonly used to describe borderline personality disorder. Cluster B personality disorders were defined as the presence of a diagnosis for this disorder (

ICD-9 codes 3011, 3013, 3015, 3017, 3018, or 3019). For schizophrenia,

ICD-9 code 295 was used and its

ICD-10 equivalent. Psychiatric disorders were those designated by

ICD-9 codes 290–319 and

ICD-10 equivalents as chosen by the Public Health Agency of Canada using the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (

26).

Prevalence rates represented rates of comorbid psychiatric and other medical conditions for patients reported between 1996 and 2017. The definition of a psychiatric hospitalization was any hospitalization in a psychiatric institute or having received a psychiatric diagnosis in any acute care hospital (ICD-9 codes 290–319). For emergency room visits, our indicator was the average number of visits during a year. Psychiatric and nonpsychiatric visits were captured separately. We also calculated the mean annual number of psychiatric consultations (by psychiatrists and family doctors) according to the physician specialty recorded in the physician claim.

Outcomes

Comorbid conditions.

We identified comorbid conditions using both physician claim and hospitalization files. An individual was considered to have a comorbid condition if they had a record with a diagnosis of a comorbid condition in the physician claim file or in the hospital discharge report between 1996 and 2017. The comorbid conditions reported in

Table 1 are thus cumulative for the year 2016–2017.

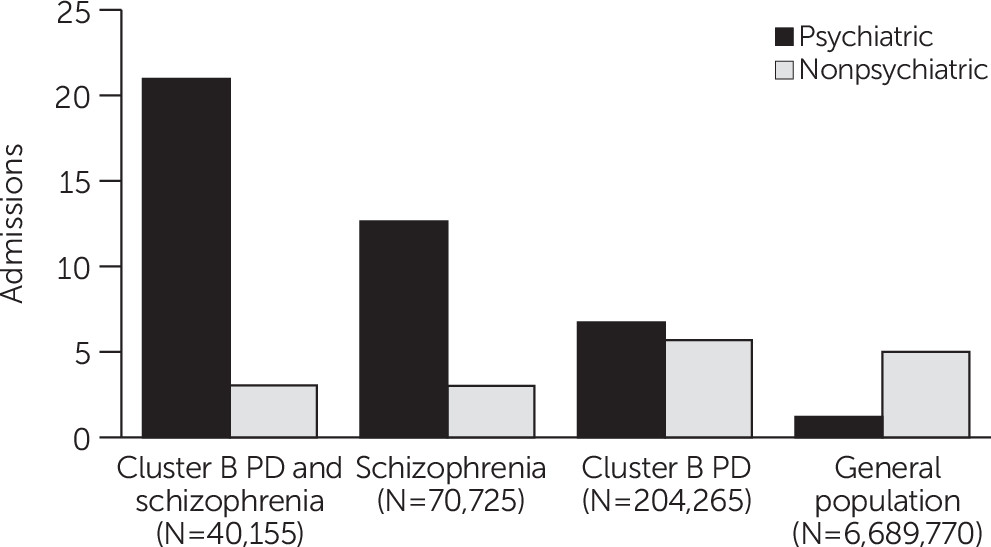

Psychiatric and nonpsychiatric hospitalizations.

Admissions to a psychiatric or general hospital with a main diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (ICD-10 codes F00–F99), which could also be listed in the hospital discharge file, were considered psychiatric hospitalizations. All other hospital admissions were considered nonpsychiatric hospitalizations.

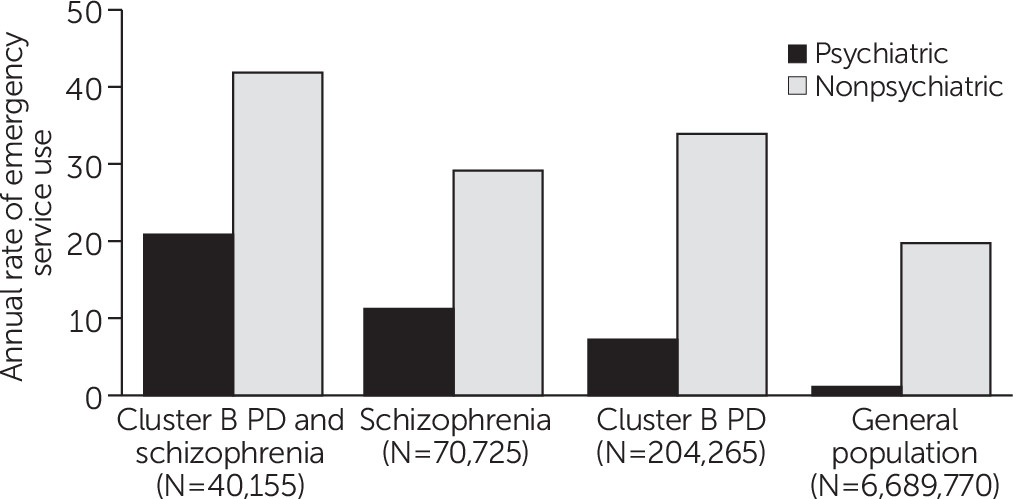

Emergency visits.

Emergency visits were determined by physician claims recorded in an emergency department. The psychiatric emergency visits were the claims billed by physicians for a psychiatric disorder diagnostic code (ICD-9 codes 290–319).

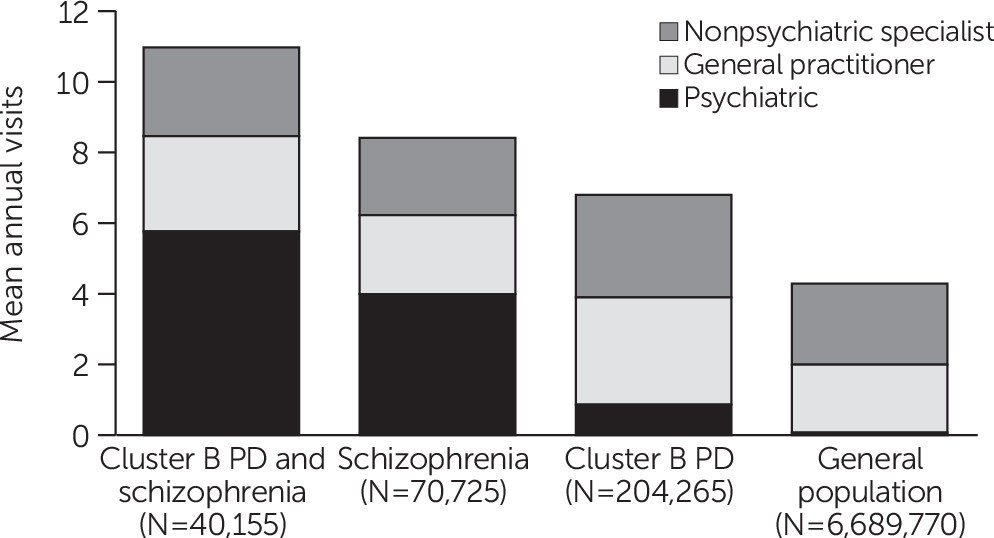

Psychiatric consultations and general practitioner and other specialist visits.

Physician claims by a psychiatrist or physician for a psychiatric disorder diagnostic code (ICD-9 codes 290–319) were considered psychiatric consultations. Physician claims billed by a general practitioner with a diagnosis code other than for psychiatric disorders were considered general practitioner visits. Physician claims billed by a specialist other than a psychiatrist with a diagnosis code other than for psychiatric disorders were considered other specialty visits.

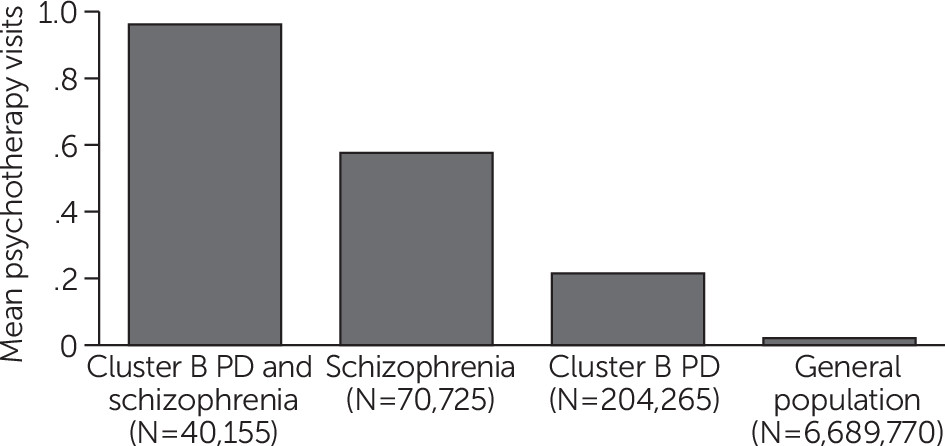

Psychotherapy.

Psychotherapy was determined with physician claims billed by a general practitioner or a psychiatrist using a psychotherapy fee code.

Statistical Analyses

All service analyses were done on the cumulative impact of personality disorders or schizophrenia (life time cases) among individuals ages ≥14 years with a confidence interval (CI) of 99%. We then computed the mean annual number of psychiatric and nonpsychiatric hospitalizations. We also calculated the average annual number of psychiatric consultations (by psychiatrists and family physicians). We conducted all the analyses using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1. The government organizations legally possessed the patient charts. The Public Health Ethics Committee and the Quebec Commission of Access to Information evaluated and approved the process of access to the QICDSS data.

Discussion

In a previous study, we estimated the prevalence of cluster B personality disorders for the province of Quebec as well as service use, excess rates, and causes of death (

12). We found lower life expectancy among patients with cluster B personality disorders than among patients with schizophrenia, especially due to suicide but also for all other causes of death (

12). To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide information on the combination of cluster B personality disorders and schizophrenia. We not only further substantiated the severity of these two disorders, separately and combined, but also their associations with patterns of service use and comorbid psychiatric and other medical conditions.

First, levels of psychiatric comorbid conditions were quite high among individuals in the three clinical groups compared with the levels of these conditions in the general population, but they were especially high among those having both disorders. Only attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder was more highly represented in the group with cluster B personality disorders than in the other two clinical groups. General medical conditions, such as neurological pathologies (i.e., epilepsy, neurodegenerative illnesses, and neurocognitive disorders), were more represented in all three clinical groups.

Second, and similarly, the use of psychiatric services (hospitalizations, emergency room visits, psychotherapy, and consultation visits) was more frequent in all three groups than in the general population, but it was highest among individuals with both disorders. Surprisingly, those with cluster B personality disorders used far less psychiatric outpatient services and psychotherapies than did patients with schizophrenia or both disorders. The patterns of service use for general medical care were also heterogeneous among the three groups. Patients with cluster B personality disorders used more medical care services than those with schizophrenia or both disorders. A possible explanation is that patients with cluster B personality disorders are less welcomed in regular psychiatric services than in the other health services available freely in Quebec’s managed care system.

However, when psychiatric and general medical care services were combined, a clear pattern emerged with respect to severity of diagnoses: the prevalence rates of comorbid conditions and patterns of service use were higher in the combined disorders group than for schizophrenia and cluster B personality disorders alone. Alternatively, when we focused on the severity of general health conditions, the order was modified, with cluster B personality disorders having the highest severity, followed by schizophrenia. These observations on the high rates of general medical comorbid conditions among those with cluster B personality disorders converge with a large body of work (

16), revealing that nonsuicide-related mortality and morbidity rates are higher in this population (

3,

12,

27). In addition to the severity conferred by the higher than expected level of general medical comorbid conditions, we can better understand the feeling of being overwhelmed among those with cluster B personality disorders as reported by family doctors in an Australian survey (

28). The combination of increased general medical conditions and reduction in well-being would partially explain the high level of service use in both populations (

21).

Our epidemiological data converge with a field of research on the common vulnerabilities (genetic, neurotoxic, and environmental), linking mental health with neurological and general medical conditions (

29,

30). Traditional nosography has distinguished the two disorders for centuries (

31). Clinically, this approach often leads to efforts to distinguish the two disorders rather than to consider them as appearing in combination (

32). However, the two disorders may clinically co-occur, for example, when patients with personality disorders may present with auditory hallucinations (

33) or with executive functioning or memory difficulties (

34); these patients may also be treated with antipsychotic medications (

35). The results in this study indicate that clinicians judge the comorbidity between the two disorders to be frequent and that it is a marker of increased disorder severity. Therapeutic and organizational strategies remain to be determined and should be organized in view of this clinical reality.

This study had various limitations. In particular, the diagnoses were not established with standardized questionnaires. Nonetheless, at least one study has compared results from administrative databases with findings from epidemiological studies, enabling us to conclude that such databases, despite having a weak sensitivity, can yield data with a strong specificity for personality disorders (

36). It is indeed possible that the population captured in this study represents the patients with the most severe cluster B personality disorders in contact with specialist and general health services. The cohort in this study corresponded to a subgroup of patients in contact with medical services and for whom a personality disorder is recognized as a problem serious enough to merit a diagnosis. More importantly, this study did not allow us to note the activities of psychologists and other mental health workers, whether in private clinics or in the local community health clinics, because such clinical activities are not captured by the QICDSS. Last, when the analyses were controlled for sex, we could not obtain other confounding factors such as socioeconomic status or age.

We can add other points of comparison with existing data in the literature documenting higher health care service use among those with cluster B personality disorders compared with control populations (

12,

20,

37). Patients with schizophrenia are known to have the highest level of service use (

11). Our data show that the severities of the schizophrenia and cluster B personality disorders can be similar. We should therefore expect a similar pattern of psychiatric service use. The differences we observed here could be explained by historical aspects, such as schizophrenia being traditionally considered by some clinicians as a more severe illness and therefore more important in psychiatric settings. Other differences may arise from relatively new data supporting the treatability of borderline personality disorder through various psychotherapies or schizophrenia’s response to pharmacological treatments, which are the focus of medical and financial attention. Mostly, we are acutely aware of the overwhelming stigma (

38,

39) associated with cluster B personality disorders and how this stigma and problems in health care organization can interfere in all aspects of health care for patients with these disorders. In all cases, none of the above hypotheses can justify the status quo of a discrepancy in health care provision for individuals with cluster B personality disorders compared with those with schizophrenia. Continued study of health care models, practices, and financing for patients is needed.

This study had multiple strengths. Notably, it had significant power of scale because we used data from an entire population in a Canadian province. Second, the findings of this study have both clinical and economical relevance because we inquired about diagnoses that require significant levels of care and thereby affect the overall health care budget. This study also reflects the complex reality of clinical practice more accurately than previous epidemiological population surveys or tertiary care clinic registers.