COVID-19 and the pandemic response caused an unprecedented disruption to health care utilization (

1–

5). Prescriptions of medications for chronic conditions in the United States increased in March 2020, the month a national emergency was declared, but declined in April 2020 (

6). Similar declines in use of pediatric prescription medication were observed beginning in April and extending through the rest of 2020 (

7). Specifically, prescription fills for medications to manage attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) declined sharply after the start of the pandemic, with smaller declines observed for prescription fills of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and tranquilizers from April to August 2020 (

7). However, prior studies did not examine medication class–specific or regional variations in prescribing that may have occurred because of local COVID-19 mitigation measures or infection rates (

8,

9), which may have affected the relative degree of social isolation, health care access, financial hardship, and loss of close relatives. Thus, we sought to examine trends in and geographic variability of prescription psychotropic medication dispensing to U.S. children and adolescents before and in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We utilized national pharmacy data from IQVIA’s U.S. longitudinal prescription data set. The longitudinal data set captures approximately 90% of retail prescription medications dispensed across the United States, irrespective of insurer or insurance type (

10). Furthermore, approximately 77% of mail-order prescriptions and 72% of prescriptions in long-term care facilities are captured. Data were provided through the IQVIA Institute Human Data Science Research Collaborative for research related to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was deemed exempt from review by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board.

We conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study examining prescription psychotropic medications dispensed to children and adolescents ages 5–18 years from January 2019 through September 2020. We sorted prescriptions into four therapeutic categories—antidepressants, antipsychotics, ADHD medications, and anxiolytics or sedatives (see the online supplement to this report)—and excluded prescriptions (N=4,245,301 of 99,885,276 [4.3%]) from U.S. territories and when the region was unknown.

Variables of interest included the age and sex of the patient and the U.S. state associated with each prescription record. States were grouped into nine geographic divisions (hereafter “regions”), as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau (

11): New England, Middle Atlantic, South Atlantic, East North Central, East South Central, West North Central, West South Central, Mountain, and Pacific.

We summed the number of psychotropic medications dispensed per month within each therapeutic category. All dispensed medications were counted (i.e., youths could have multiple prescriptions within a month). We then estimated the percent change in monthly dispensing from January to September 2020 compared with the same months in 2019. For example, for March, the percent change was calculated by subtracting the number of medications dispensed in March 2019 from those in March 2020 and dividing the result by the number of medications dispensed in March 2019. We selected March 2020 as the beginning of the pandemic period on the basis of the national emergency declaration in the United States. The percent change for each month was estimated overall for the United States and by U.S. region.

To provide a summary of changes in pediatric psychotropic medication dispensing in the first months of the pandemic, we calculated the overall percent change from March to September 2020 versus March to September 2019 on the basis of the prescribed medications dispensed during these two 7-month periods.

Results

During the study period, 95,639,975 psychotropic medications were dispensed to children and adolescents. The median age from all prescription records was 13 years (interquartile range 10–16); 39.3% (N=37,541,184) of all included prescription medications were dispensed to females.

Figure S1 in the online supplement depicts the percent change for each month in 2020 versus 2019 (January–September), by medication class. The general pattern was similar for most medication classes considered, with increased dispensing (vs. 2019) in March 2020, followed by a decrease in April 2020 that continued in May 2020. By September 2020, many, but not all, medication classes had rebounded to dispensing levels similar to those in September 2019.

Of the medications examined, the largest declines in dispensing occurred for stimulants (–26.4%, N=1,569,666 in May 2020 vs. N=2,132,728 in May 2019) and benzodiazepines (–21.2%, N=85,019 in April 2020 vs. N=107,854 in April 2019). (A negative percentage indicates that fewer prescribed medications were dispensed during a given month in 2020 compared with the same month in 2019.) Nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytics had a minimal decline (–3.4%, N=48,118 in May 2020 vs. N=49,811 in May 2019). The magnitude of observed change varied within the therapeutic categories. For example, within the ADHD medications category, the percent change per month for stimulants ranged from −3.5% (N=2,099,157 in March 2020 vs. N=2,176,003 in March 2019) to −26.4% (May 2020 vs. May 2019), whereas the percent change for alpha-agonists ranged from 9.4% (N=781,729 in March 2020 vs. N=714,859 in March 2019) to −6.2% (N=683,366 in May 2020 vs. N=728,403 in May 2019).

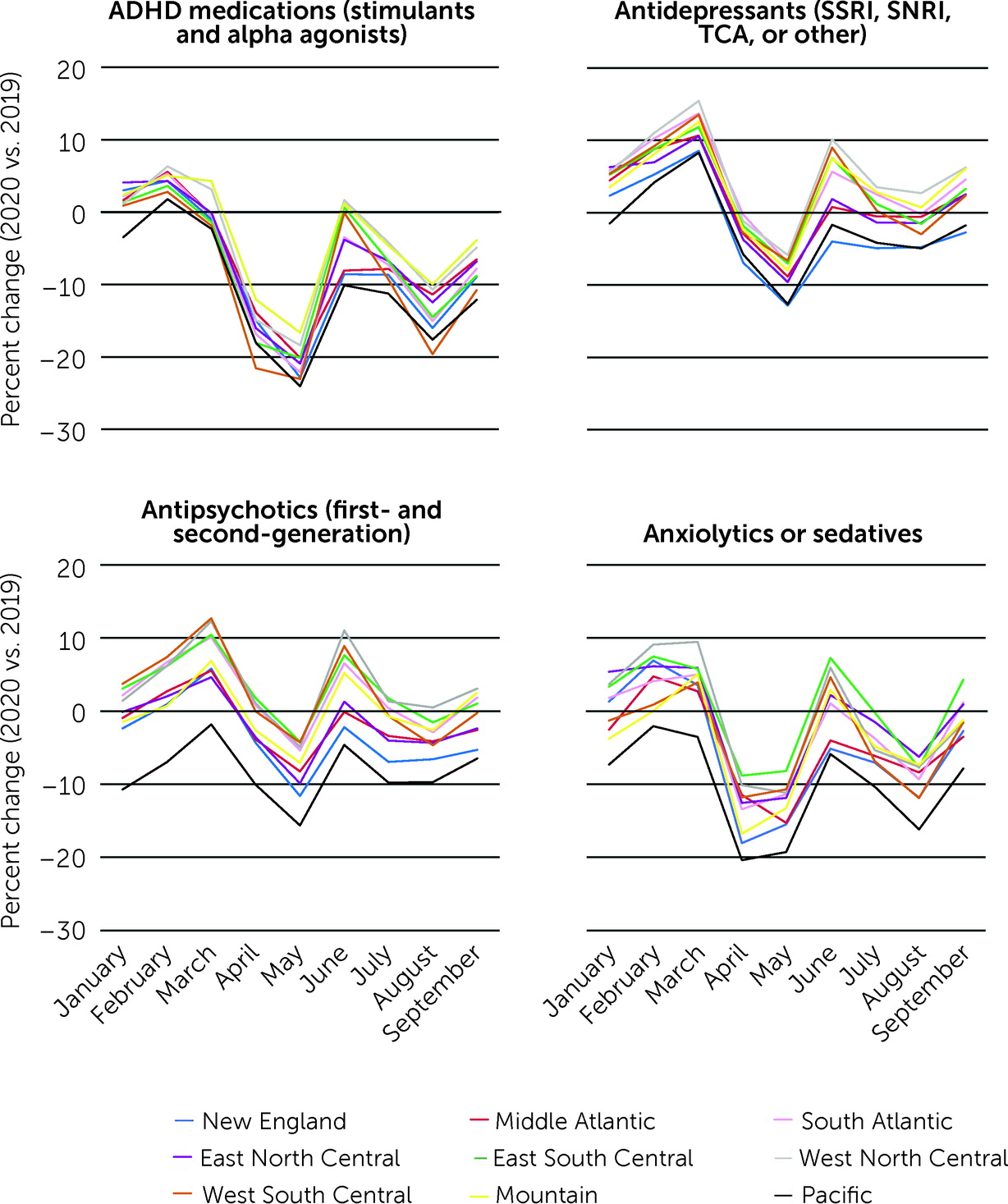

Overall trends were similar across regions; however, the magnitude of change in pediatric psychotropic medication dispensing in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic versus the same period in 2019 varied (

Figure 1). In general, the monthly percent change in psychotropic medication dispensing from March to September 2020 versus the same period in 2019 was greatest in the Pacific and New England regions, reflecting, in part, variation in prepandemic changes (January–February 2020 vs. 2019).

Regional percent change in dispensing in March 2020 versus March 2019 ranged from −2.3% (N=197,425 vs. N=202,137) to 4.6% (N=153,812 vs. N=147,064) for ADHD medications, 8.3% (N=133,520 vs. N=123,302) to 15.5% (N=145,799 vs. N=126,285) for antidepressants, −1.8% (N=29,847 vs. N=30,402) to 12.7% (N=66,785 vs. N=59,262) for antipsychotics, and −3.5% (N=14,839 vs. N=15,382) to 9.5% (N=14,197 vs. N=12,967) for anxiolytics or sedatives. In May 2020, the month with the largest overall decline in dispensing, regional percent change versus 2019 ranged from −16.6% (N=123,002 vs. N=147,555) to −24.1% (N=159,069 vs. N=209,455) for ADHD medications, −5.9% (N=124,428 vs. N=132,176) to −12.8% (N=74,861 vs. N=85,885) for antidepressants, −4.2% (N=29,952 vs. N=31,269) to −15.6% (N=27,111 vs. N=32,133) for antipsychotics, and −8.2% (N=11,827 vs. N=12,882) to −19.3% (N=12,760 vs. N=15,807) for anxiolytics or sedatives. By September 2020, the number of medications dispensed rebounded to prepandemic levels for some regions. However, all regions had fewer ADHD medications dispensed in September 2020 versus September 2019, ranging from −3.9% (N=139,138 vs. N=144,749) in the Mountain region to −12.1% (N=169,247 vs. N=192,550) in the Pacific region (

Figure 1).

Differences in psychotropic medication dispensing from March to September 2020 versus March to September 2019, by therapeutic category and geographic region, are summarized in the online supplement. In the first 7 months of the pandemic, fewer antipsychotics (N=138,757 in 2020 vs. N=145,327 in 2019) and antidepressants (N=556,249 in 2020 vs. N=579,522 in 2019) were dispensed in New England, compared with the same period in 2019. In contrast, in the West North Central region, more antipsychotics (N=254,350 in 2020 vs. N=246,118 in 2019) and antidepressants (N=935,600 in 2020 vs. N=897,173 in 2019) were dispensed in 2020.

Discussion

Overall, fewer psychotropic medications were dispensed to U.S. children and adolescents early in the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the prepandemic period. Despite overall similar trends across the nine U.S. regions, the magnitude of change in psychotropic medication dispensing varied by region. The most profound declines in dispensing across psychotropic medication classes and geographic regions occurred from April to May 2020. Although dispensing levels in some regions rebounded to prepandemic levels by September 2020, they varied by medication class and region.

Similar to prior studies (

6,

7,

12), we observed declines in dispensing of stimulants, which by September 2020 remained below 2019 levels across all regions. This observation could be associated with the shift to at-home virtual learning instituted by many U.S. schools. A prior study that used U.S. prescription medication dispensing data showed relatively little change in pediatric antidepressant (−0.1%), antipsychotic (−1.8%), and tranquilizer (−1.0%) dispensing from April to August 2020, compared with 2019 (

7). We observed that the percent change varied considerably by month (from March to September) and by medication class. In particular, dispensing of nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytics (which consisted mostly of buspirone prescriptions) remained at or above prepandemic levels, except in May, partly reflecting prepandemic rises in usage. Larger declines were observed for benzodiazepines, which may be unique to this younger age group; in another study of benzodiazepine prescription fills among U.S. adults and children, a decline was not observed in the first months of the pandemic (

13).

We observed regional variation in the magnitude of change in pediatric psychotropic medication dispensing before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Regional variation has also been seen in other aspects of health care utilization. For example, telemedicine uptake after the start of the pandemic varied by region, with the highest uptake occurring in the Pacific region (

5). Access to and need for pediatric psychotropic medications may have varied because of local COVID-19 infection rates, local mitigation policies (

8) (e.g., school closures), social isolation, limited access to health care, or other community stressors.

Evaluating changes in the use of psychotropic medication among children is critical given the profound societal disruptions caused by the pandemic and reports of rising prevalence of mental health issues among children (

14,

15). Those findings, along with the declines and variability in psychotropic medication dispensing that we observed, suggest the importance of focused attention to specific mental health treatment needs of children and adolescents across the United States.

Our study had several notable strengths. Our data set captured prescription psychotropic medications dispensed to children and adolescents across the United States, irrespective of insurance type or insurance status. The large sample enabled us to perform subgroup analyses to characterize geographic trends and variability in dispensing of different classes of psychotropic medications.

Our study also had certain limitations. Given the available data, we were unable to examine psychotropic medication dispensing beyond September 2020. Our estimates of dispensing rates assumed a consistent source population over the study period. The data captured in this study were related to psychotropic medication dispensing for a mix of children and adolescents who continued medication treatment through the pandemic, those who stopped treatment after the pandemic started, and those who initiated treatment after the pandemic started. We were unable to distinguish among these three groups of youths, and we could not make inferences about the indications for treatment. Furthermore, we could not determine whether medications were overprescribed before or during the pandemic or whether observed declines in psychotropic medication dispensing during the pandemic indicated youths with unmet treatment needs, because not all youths with psychiatric disorders require or receive pharmacological treatment. Prescriptions for 18-year-olds were included; changes in insurance and psychotropic prescribing related to COVID-19 in this age group may have been different from those among younger children and adolescents. Prescription claims generally represent only filled or picked-up prescriptions, but an unfilled prescription may occasionally be captured. Days’ supply of prescribed psychotropic medications was not evaluated; increases in patients’ prescribed days’ supply during the pandemic would likely result in fewer prescription fills.