The peer (lived experience) workforce has grown in Australia and internationally, and peer workers are now a central part of the mental health services sector (

1–

3). However, the rapid growth in peer workers has been described as ad hoc and lacking in structure (

4–

6). This lack of structure has resulted in role confusion and wide variability in responsibilities, training, pay scales, and job titles, impeding effective implementation and integration of peer workers within mental health services (

4,

6). In response, several countries have initiated training programs and certification standards for peer workers to enhance the legitimacy of these roles and to provide greater standardization across the peer workforce (

7–

10). However, in contrast to countries, such as the United States, where policies mandate certification of peer specialists, no licensure requirements currently exist for peer workers in Australia (

11–

13).

The term “peer workforce” traditionally refers to workers who are employed specifically because of their expertise and experience in navigating their own mental health challenges as service users (“consumers”) (

14,

15). In Australia, however, the peer workforce increasingly also includes “carer” workers who are employed because of their knowledge and experience in supporting a family member who has a mental health challenge (

1,

16,

17). (Carers correspond to “caregivers” in the U.S. health care system, used hereafter.) The rationalization to collectively refer to these workforces under the umbrella of lived experience is based on the understanding that both consumer and caregiver workers draw on their own experience in their work roles (

1,

17).

Previous research (

18–

20) has focused on understanding and evaluating the peer workforce comprising people with experience as consumers of mental health services and assessing the effectiveness of this workforce in achieving positive outcomes for people receiving this support. In contrast, research on caregiver peer roles has been limited (

17), although results from the existing literature (

17,

21) have indicated that caregiver peer roles effectively support caregivers. Moreover, little is known about the differences between the two workforces. The available literature indicates that the essential experiences that inform consumer or caregiver work result in different scopes of practice (

22), such as consumer peer roles that support and advocate for people accessing services and caregiver peer roles that support and advocate for individuals who care for a family member (

23). Likewise, findings of a recent study (

24) suggest the importance of people accessing services to receive support from someone with consumer rather than caregiver experience and the need to distinguish between the two kinds of peer workers to reduce role confusion. Other studies (

25–

27) have shown that the distinct perspectives arising from differences between the consumer and caregiver experiences result in different work practices.

An increasing number of peer workers have combined consumer and caregiver roles informed by both perspectives (

22). However, the literature on peer-support positions that combine consumer and caregiver experiences is scarce. This study explored perceptions of the similarities and differences between the consumer and caregiver peer workforces in Australia and views on combined consumer-caregiver positions.

Methods

Design

This survey was part of a nationwide study exploring the Australian peer workforce. Participants included workers in designated peer and nondesignated positions. Nondesignated roles included employees, such as mental health support workers and clinicians, who are not employed to work from their lived experience.

Survey questions were mainly multiple choice, with some open-ended questions allowing for additional comments. The survey was distributed online through mental health networks, e-mail, and social media. Recruitment was through a snowball-sampling technique, with organizations and individuals being asked to assist in sharing the survey with potential participants. Participants were provided information about the research and consented to participate by progressing to the survey. Ethics approval was obtained from the RMIT University’s human research ethics committee (HREC22527). Two of the authors (H.R. and L.B.) are in designated peer research roles.

Analysis

A sequential mixed-methods approach (

28) was used to guide the analysis, first by analyzing the quantitative data and then by integrating the qualitative data. The quantitative analysis was done with SPSS, version 26, and examined responses to the three following questions: “How similar or different are the values or goals of consumer and caregiver or family roles?” “How similar or different are the work practices of consumer and caregiver or family roles?” “In your opinion, is it appropriate for organizations to design roles that combine consumer and caregiver perspectives?” The first two questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1, completely different; 2, somewhat different; 3, neutral; 4, somewhat similar; 5, very similar) and responses to the third question included three options (yes, no, or not sure).

Two one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted, with personal experience as the independent variable (consumer, caregiver, both, neither, or chose not to say). All participants were asked whether they had experience accessing services for themselves or as a caregiver for someone with mental health challenges. The dependent variables were the similarity of values or goals and work practices. Additionally, two 2×3 fully between-subjects factorial ANOVAs were conducted with the same dependent variables as above. The independent variables were peer status (peer designated and nondesignated) and opinion on combining consumer and caregiver peer roles (yes, no, and not sure). Finally, correlations between the same dependent variables and tenure (<5, 5–10, 11–15, 16–20, ≥21 years) were examined. All analyses were assessed at α=0.05, with significant main effects explored further by using Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc tests.

A qualitative analysis was then conducted by using the open-ended responses from the survey. Open-ended question 4 allowed participants to comment on the similarities and differences in the values, goals, and work practices between the roles. Question 5 asked how roles that combined consumer and caregiver perspectives were perceived.

Reflexive thematic analysis and coding of qualitative responses were conducted according to the method by Braun and Clarke (

29). An inductive approach was used, and analyses were guided by the data rather than by a preconceived framework or hypothesized themes (

30). The first and third authors conducted the thematic analysis by examining the responses several times and generating codes for potential patterns before settling on meaning (

30).

Results

In total, 882 individuals participated in the survey. The sample included 558 individuals employed in designated peer roles and 324 employed in nondesignated roles. Because the peer workforce is expanding rapidly in Australia, ascertaining the total number of designated roles was difficult. Similarly, the study focused on participants working within multidisciplinary teams rather than being part of the total population of the mental health workforce. Despite challenges in obtaining population data for designated roles, our findings appeared robust relative to those of a previous national study (with 305 designated peer workers) (

22).

Qualitative responses were predominantly from designated peer staff. Responses to question 4 were from 168 people in designated peer roles and 56 people in nondesignated roles; question 5 responses were from 185 people in peer roles and 79 people in nondesignated roles. Demographic data indicated that participants were from all states and territories within Australia and varied in lengths of tenure, role functions, and perspectives (

Table 1). Most peer participants were employed in direct support roles, working from a consumer perspective. Only 12% (N=21) of participants in nondesignated roles identified as having neither consumer nor caregiving experience.

The results below represent an integrative analysis of quantitative and qualitative data. Integration of the results showed that the qualitative analysis added clarity to the quantitative findings. Both the qualitative and quantitative results showed that people in designated consumer roles, and participants in any role type who had themselves accessed services, had values and goals that differed greatly from those with no consumer experience.

Perceived Differences in Consumer and Caregiver Perspectives

The quantitative data showed that the more experience the individual had in a consumer peer position, the greater their perceived differences in goals, values, and work practices from those in only caregiver positions. The qualitative analysis revealed perceived differences in perspectives between participants with consumer and those with caregiver experience, as well as concern—based on the differences in perspectives—about staff positions that combined these roles.

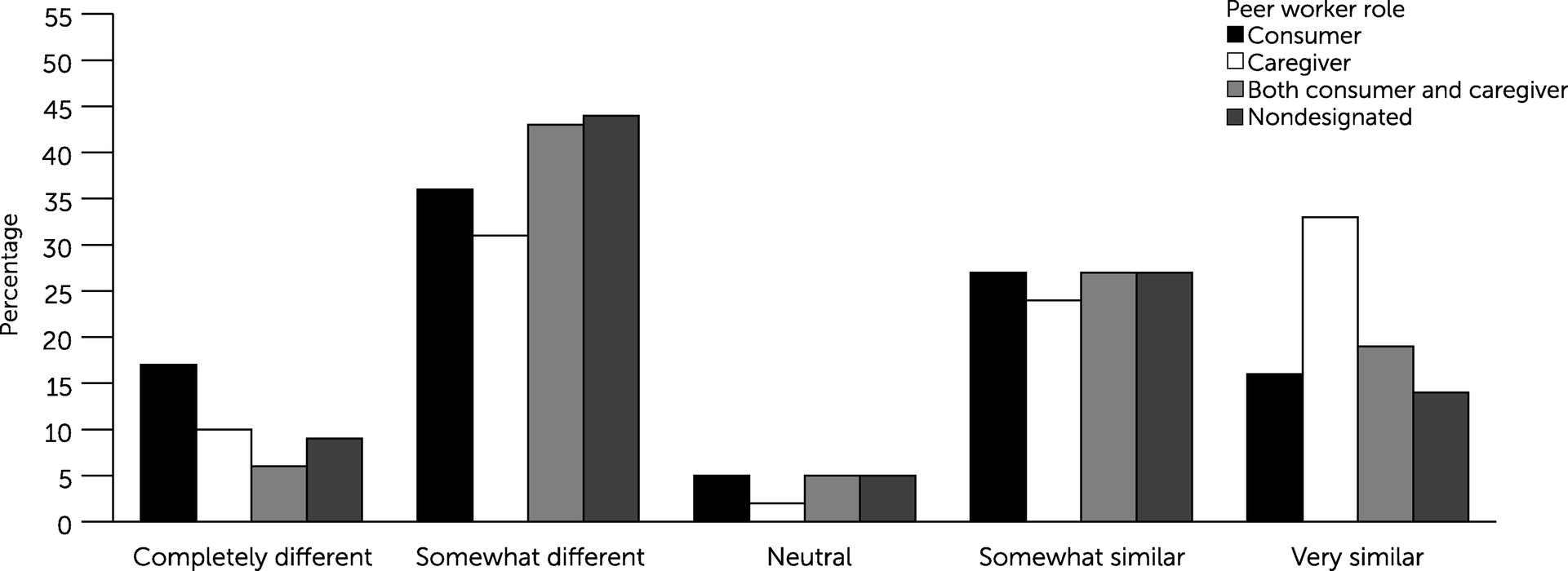

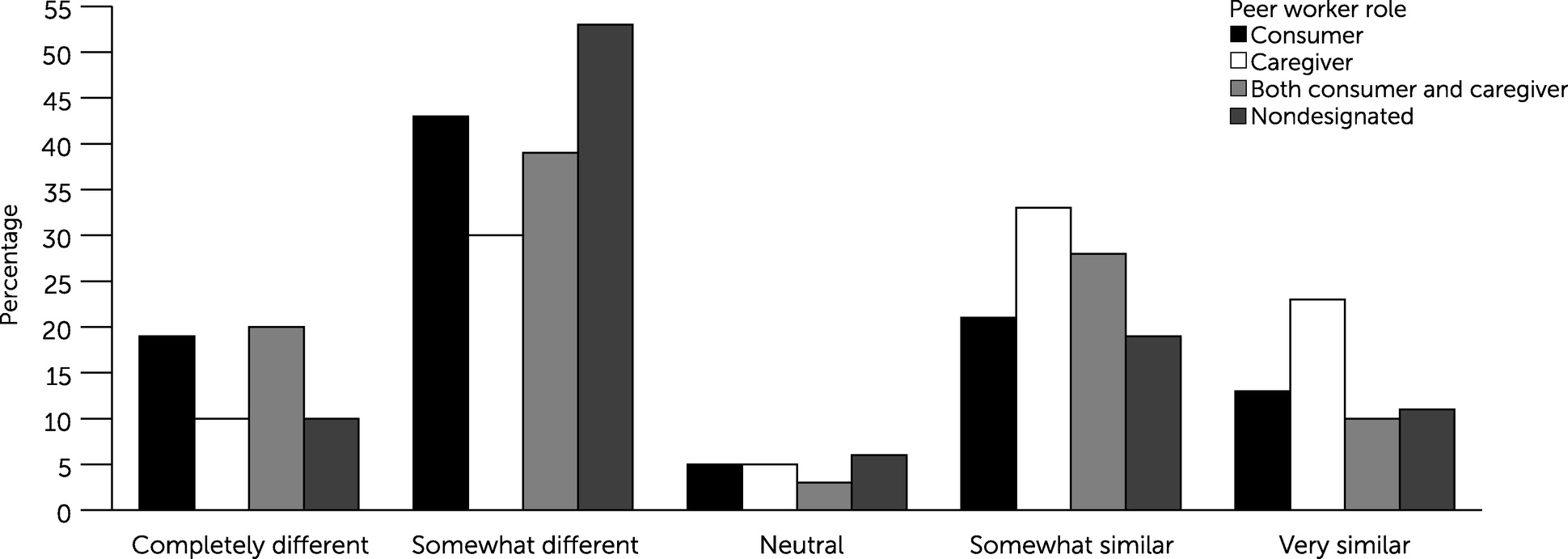

The quantitative results indicated that most participants viewed the two perspectives as different in terms of values or goals (51%, N=196 of 386), as well as work practices (59%, N=220 of 376), with fewer participants providing neutral responses on the survey or stating that the two workforces had similar goals or values (5%, N=18 of 386, and 45%, N=172 of 386, respectively) and work practices (5%, N=18 of 376, and 37%, N=138 of 376, respectively). The qualitative data contributed to our understanding of the perceived differences and similarities between the consumer and caregiver workforces, as shown in the following themes and subthemes.

Distinct Peer Roles

Participants in consumer, caregiver, or nondesignated workforce positions noted more differences than similarities between the consumer and caregiver workforces. Reinforcing the quantitative data, participants in consumer roles shared more about these differences than did participants in caregiver or nondesignated roles. Participants’ views were identified as differences in perspectives, priorities, and work practices as described in the following.

Different perspectives.

“Perspective” refers to the individual and collective experiences and knowledge workers brought to their role as individuals with consumer or caregiver experience. Perspectives stood out as a clear distinction between the workforces.

The consumer is centered on emancipating . . . other consumers and herself, as well as changing . . . systemic inequalities from a consumer’s perspective. The carer is centered on emancipating . . . other carers and herself, as well as changing . . . systemic inequalities from a carer’s perspective. (consumer peer participant)

Different priorities.

Understanding the role of power and the loss of human rights experienced by people involuntarily receiving mental health services translated to varying priorities in the relative importance of autonomy versus safety. The following comment illustrates the tension between consumer and caregiver roles and potential for conflict between the two perspectives.

Today, I overheard my carer colleague advocating for a consumer to be treated against their will, because it was in the “best interests” of the family. As a consumer worker, I would NEVER advocate for something that would knowingly bring harm to someone else. (consumer peer participant)

Different work practices.

The differences in expertise between consumer and caregiver peers translated to nuances in working with the needs of people accessing services (consumers) or their families.

As a consumer peer worker, I would not begin to understand the experiences of carers [or] family. If a carer contacted me, I would refer them to the carer peer worker(s) who can support them more effectively. I would expect the carer workers to refer the consumer in a family they are supporting to me as the consumer worker. (consumer peer participant)

Perceived Similarities in Consumer and Caregiver Roles

Although differences between caregiver and consumer roles were often mentioned by the respondents, study participants also identified similarities, including values of authenticity, transparency, hope, self-determination, reciprocity, mutuality, and self-determination.

Both roles involve sharing lived experiences to build rapport, validation, and hope, while assisting the people they are working with to look at strengths, goals, and healthy coping strategies to enhance self-care, advocacy, and resilience. (caregiver peer participant)

Participants also discussed similar goals of working toward personal recovery that underpinned practice in both caregiver and consumer roles.

I think essentially the roles are similar, in that supporting someone experiencing significant emotional distress can be a stigmatising and demoralising experience that changes one’s sense of self. The role of both consumer and carer lived experience staff is to support people [and] services in moving forward. (participant in a nondesignated role)

Quantitative data also reflected variability in perceived similarities and differences regarding values and goals (

Figure 1) and work practices (

Figure 2) for participants across the four cohorts (people employed in consumer, caregiver, combined, and nondesignated roles).

Identification with personal experience.

Results from a one-way ANOVA indicated a significant difference between participants who primarily identified as consumers and participants who primarily identified as caregivers in the perceived level of similarity between consumer and caregiver values or goals (F=3.51, df=4 and 575, p=0.008). Regardless of their professional role, participants’ personal identification as having been a consumer or caregiver was related to their perceptions of differences in consumer and caregiver workforce values and goals.

Peers who identified as having lived experience as consumers noted that the values and goals of the consumer and caregiver workforces were significantly different from the values and goals of participants identifying as having both consumer and caregiver experiences (MDiff=−0.63, p=0.009), those who identified as having neither consumer nor caregiver experience (MDiff=−0.79, p=0.009), and those who chose not to say (MDiff=−0.39, p=0.004). No other differences, including between those who had consumer experience and those who had caregiving experience, were statistically significant (at α=0.05). A one-way ANOVA, stratified by type of personal experience, found no significant differences in perceived similarity between consumer and caregiver work practices.

Length of tenure.

Length of tenure in a peer role was examined to determine whether it influenced the perception of similarities and differences among the different roles. Bivariate correlations indicated a significant positive relationship for those working in designated consumer roles between length of experience in their role and higher perceived differences in values or goals and work practices between the consumer and caregiver workforces (r=0.21, p<0.001, and r=0.10, p=0.05, respectively). No such relationships were found for length of tenure for those working in a designated caregiver role.

Views Regarding Combined Roles

When asked to comment on roles that combine both consumer and caregiver perspectives, most of the participants in peer and nondesignated roles indicated that the two roles should not be combined. Participants’ opinions were grouped under the following themes: potential risks in combining consumer and caregiver roles and the possibility of combining roles in specific contexts.

Potential risks in combining consumer and caregiver roles.

Participants identified risks concerning who was being represented by combined roles and the potential for tension when combining both perspectives in a single position. Combining the two roles also raised concerns that people accessing services might have difficulty forming a support alliance with a peer worker serving in a combined role, particularly when participants had experienced trauma involving family members or caregivers.

Potential for fundamental conflict re[garding] who is being supported or represented. Risk for consumers who have experienced trauma—why would they trust someone who identifies as a “carer,” when that word may have a negative meaning for them. (consumer peer participant)

Possibility for combined roles in specific contexts.

Some participants suggested that combined roles may sometimes be useful in areas where peers do not work directly with people accessing services, such as policy making and research.

[Roles should be combined] only in certain contexts, where both consumers and carers are the subject of the service, policy, [or] research, . . . and where the role is focused on business functions or processes that are largely common. Many lived experience workers have experience of both and can apply their experience flexibly, depending on need. (combined role peer participant)

However, other participants identified considerations that would need to be in place, including workers having in-depth experience as both a person accessing services and supporting others.

I think these roles could be useful, but steps would have to be taken to ensure that the person hired has an appropriate amount of experience in both situations. (consumer peer participant)

The quantitative results regarding whether combining consumer and caregiver roles was deemed appropriate showed that only 41% (N=110 of 271) of consumer peers, 36% (N=15 of 42) of caregiver peers, and 44% (N=82 of 185) of nondesignated employees thought that combined roles were appropriate. However, most participants working in a combined role (64%, N=40 of 63) indicated that having roles for people with a combined perspective was appropriate.

An ANOVA to examine the relationship between perceived similarities between the workforces and opinions on combined roles compared participants’ answers on the first three survey questions. Respondents who endorsed that roles should not be combined noted significantly fewer similarities in work practices between the consumer and caregiver workforces (mean±SD score=2.31±1.44) than did those who thought the roles should be combined (mean score=2.97±1.40) and those who were unsure (mean score=2.91±1.34) (p<0.001). Similarly, participants who thought that roles should not be combined noted significantly fewer similarities in values and goals between the consumer and caregiver roles (mean score=2.59±1.46) than did those who thought that roles should be combined (mean score=3.23±1.43, p<0.001) and those who were unsure (mean score=3.08±1.36, p=0.003). No significant differences were detected, on the basis of worker status, between perceived similarities in work practices or values and goals.

Discussion

The lived experiences informing the consumer and caregiver peer roles differed between the two roles. Consumer peer workers had direct experience of accessing services and the common consequences of loss of autonomy and detrimental impacts on sense of self (

31–

33). In contrast, caregiver peer workers had witnessed, walked alongside, and supported someone having these experiences (

17). Our findings showed inadequate understanding among both peer and nondesignated workers of how these differing experiences inform values, goals, and work practices. Correspondingly, existing research (

4,

6,

34,

35) has highlighted low role clarity for peer workers and poor understanding of peer roles among the wider mental health workforce. This study provided insight into distinctions between peer roles for consumers and caregivers, examined the appropriateness of combined roles, and highlighted areas for further exploration.

Results from the qualitative analysis stressed the unique perspectives of consumer and caregiver roles arising from these groups’ diverse experiences, which manifested as differences in priorities and work practices. Furthermore, differing priorities and work practices resulted in the belief that there were conflicting agendas and tension between the consumer and caregiver roles concerning the importance of patient autonomy and safety. This finding was supported by results of previous studies that have recognized competing needs of consumers and caregivers and challenges in balancing the right of consumers to self-determination against caregivers’ desires to emphasize consumer safety, even when safety impinges on consumers’ autonomy or human rights (

26). Research (

21,

36) on the role of caregivers in the involuntary treatment of consumers has shown how consumer and caregiver perspectives can differ on these crucial points.

Because accredited training for consumer peer roles is limited, much discipline-specific learning and skill development occurs during employment (

37). Therefore, the tendency of consumer workers with longer tenures to see differences in the role types suggested that the depth of understanding of role-specific values and goals influenced perceptions of how consumer roles differ from caregiver roles. Conversely, greater perceived similarity between the roles expressed by people in caregiver roles may have reflected the relative novelty of these roles, the limited research, and the lack of role-specific training available to guide people in caregiver positions compared with consumer positions (

17).

Most study participants stressed the need for distinct consumer and caregiver roles, rather than combined roles. The voiced need for distinct roles and explicit scopes of practice of peer roles is consistent with existing research (

24), indicating that confusion between role tasks often raises concerns regarding the appropriateness of consumers receiving direct support from caregiver peer workers. Similarly, the call for greater understanding and valuing of caregiver roles has been supported by evidence that caregiver roles support better outcomes for caregivers (

21,

38). However, some participants’ views agreed with findings in previous studies (

25,

39) that have shown that combined roles for those with both consumer and caregiver perspectives may have value in areas of indirect work, such as service development, policy, and evaluation.

The results of this study underscore the need for further research to better understand differences and similarities between consumer and caregiver peer workers and to inform role-specific training for both types. Given the confusion regarding consumer and caregiver roles, combining both roles may compound existing poor role clarity within the peer workforce. To mitigate role confusion, combined caregiver and consumer peer positions, particularly in the provision of direct support, are not recommended. Research is needed to further develop and clarify the different role requirements, responsibilities, and diverse perspectives that inform the work of peer supporters.

This study was limited by the greater representation of consumer compared with caregiver respondents in the survey; however, this imbalance is typical of the composition of the peer workforce. Self-reporting bias was also identified, whereby those who viewed the roles as different and combined roles as inappropriate were more likely to provide qualitative responses. Therefore, qualitative data unequally represented views against using combined roles. However, we found that those who objected to the use of combined roles had longer professional experience in consumer roles and therefore offered valuable insight.

Conclusions

The findings of this study contribute to an understanding of the differences between the consumer and caregiver peer workforces and of where gaps in knowledge remain. Although the findings improve understanding of the implications of combining consumer and caregiver perspectives into a single role, further research should gather a more diverse representation of views and should more deeply examine each role type to gain better role clarity for both.