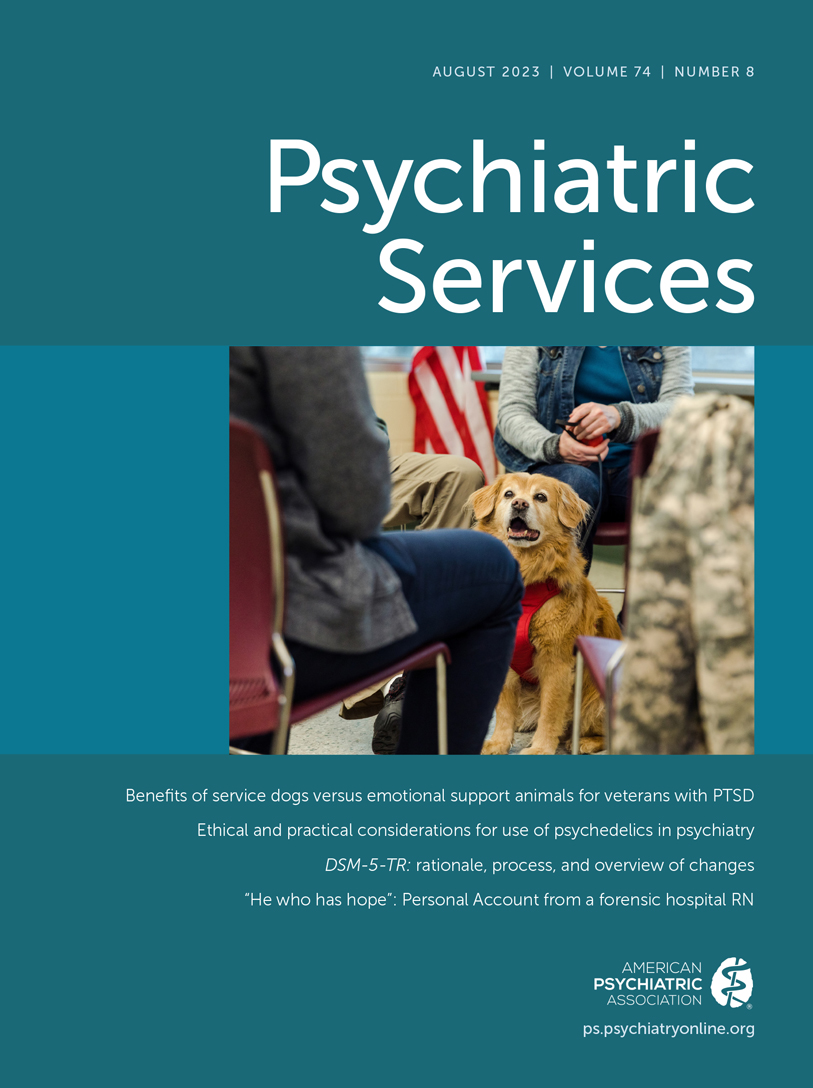

Psychedelic substances have been used for thousands of years by Indigenous communities in healing and religious ceremonies. In the mid-20th century, the U.S. federal government became interested in using psychedelics to treat a variety of mental illnesses, funding more than 100 clinical trials between the 1950s and the 1970s (

1). At that time, the medical community, including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), was enthusiastic about the potential of compounds such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) to treat mental illness (

2). Psychedelics were studied as treatment for patients with a range of psychiatric conditions, including alcohol use disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), depression, and autism spectrum disorder, and for patients with cancer experiencing end-of-life anxiety.

In the late 1960s, opposition to psychedelics—and to the countercultural movement that had embraced psychedelic use—took hold. The U.S. federal government came to view LSD as a danger to social cohesion, and research promoted claims of its teratogenic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic potential (

3). Although these safety risks were later discredited, the Nixon Administration placed psilocybin and LSD on Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 (

4), deeming that they had no legitimate medical use. In 1985, the compound 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), whose popularity was surging at the time, was also declared a Schedule I substance. Amid this political environment, research on psychedelics was largely abandoned between the 1970s and the 1990s.

Psychedelics started making a comeback in certain research circles by the 1990s. The era of modern psychedelic research has focused primarily on psilocybin, a classical psychedelic found in the

Psilocybe genus of mushrooms, and MDMA, a synthetic amphetamine derivative in the subgroup of psychedelics called empathogens. In the past decade, several trials have investigated psilocybin’s role in treating major depressive disorder (

5), alcohol and nicotine addiction (

6,

7), and anxiety disorders (

8). Research on MDMA has primarily focused on its role in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Currently, studies are under way or being planned to investigate the use of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, bipolar depression, suicidality, depression related to early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, anxiety, OCD, and substance use disorders, and more studies on the use of MDMA for PTSD are also under way.

As psychedelics have reentered the realm of rigorous scientific inquiry, they have garnered much attention from both the psychiatric community and the broader public. Headlines on major media platforms frequently tout the psychedelic future of psychiatry, and patients increasingly ask about the prospect of using psychedelics during therapy. Despite this enthusiasm, however, clinical studies on psychedelics are still in a relatively early stage, and more research and regulatory work are required before psychedelics can be deemed appropriate for general clinical use. In this climate, psychiatrists are increasingly curious about the prospects of psychedelic treatments. This review focuses on several of the ethical and practical issues surrounding psychedelics in psychiatry, and it also discusses issues for psychiatrists to consider should psychedelics become available for broad clinical use.

Current State of Psychedelic Research

The research landscape for psychedelics is progressing rapidly. The first phase 3 clinical trial for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD was published in May 2021 (

11), and several phase 2 clinical trials of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression have been published to date (

5,

12). Several trials have demonstrated large and sustained effects of psilocybin in conjunction with psychotherapeutic support.

In these carefully controlled research settings, the safety profiles of MDMA and psilocybin have been encouraging. For MDMA, the most common adverse events are mild and transient and include muscle tightness, decreased appetite, nausea, hyperhidrosis, feeling cold, and an increase in blood pressure. In the trial mentioned earlier (

11), MDMA use did not appear to increase the risk for substance abuse, and no effect on QT prolongation was found. Psilocybin’s adverse effects were also mostly mild and transient, consisting of headaches, body shaking, and anxiety. Some patients have reported intense but transient emotional distress during the psilocybin experience. At this time, psilocybin is thought to have relatively low abuse potential; conversely, it has shown promise in treating addiction, including tobacco use disorder (

13). However, more research is required to fully ascertain the safety profiles of both MDMA and psilocybin.

The effects of psychedelics on suicidality are still not fully clear. Mitchell et al. (

11) found no effect of MDMA on suicidality relative to placebo. Several participants had suicidal ideation at baseline, and some patients in both the placebo and MDMA groups experienced suicidal ideation during the trial. In Davis et al.’s randomized clinical trial (

5), participants had low suicidality at baseline, and this aspect trended lower after patients underwent psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Psychedelics’ impact on suicidality remains an area of active investigation.

Ethical Principles

Psychedelic treatments involve a range of unique ethical and practical considerations. This review is intended to assist psychiatrists with some of the issues they may face regarding psychedelic therapies in clinical practice.

Research Equipoise Amid High Enthusiasm for Psychedelics

Despite widespread media attention and claims that “psychiatry may never be the same” (

14), psychedelic therapies remain in a relatively early stage of research.

Research equipoise refers to both an epistemic (a state of knowledge) and an ethical disposition, requiring researchers and clinicians to remain neutral as they follow the scientific process to investigate the veracity of a hypothesis. This principle requires an unbiased stance regarding psychedelics’ safety and efficacy until persuasive data from clinical trials accumulate. Equipoise demands that researchers and clinicians do not decide what is true before the science informs their decision. Equipoise is a stance that allows scientific inquiry to guide beliefs, not the other way around; it is a requirement for ensuring that treatments work and are not harming patients.

However, equipoise is not binary: one does not entirely disbelieve until truth becomes apparent all at once. As evidence accrues in favor of or against a treatment, people incrementally update their beliefs accordingly. Given the current body of evidence, one can be reasonably optimistic that MDMA- and psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy could be useful in treating various mental illnesses. However, optimism should be balanced with the acknowledgment that more work needs to be done to justify a full embrace of either MDMA or psilocybin (as well as other psychedelics that are at earlier stages of research).

Equipoise also takes into account patients’ unmet needs. Up to 30% of patients with major depressive disorder do not respond to multiple treatments and are considered to have treatment-resistant depression (

15). Similarly high rates of treatment resistance exist for PTSD (

16). For these patients, among whom the risk for adverse consequences—including suicide—is greater, solutions are urgently needed. These findings demand that the research community throw its efforts into new interventions, including psychedelics.

Such needs have also been a driving force of enthusiasm for psychedelic therapies. Although early positive results are encouraging, psychiatrists should avoid being swayed too heavily by the headlines. For example, one commonly discussed development is the FDA’s 2017 designation of MDMA as a breakthrough therapy for PTSD (

17) and its 2019 designation of psilocybin as a breakthrough therapy for major depressive disorder (

18). This type of designation is granted on the basis of positive early results in clinical trials and provides specific pharmaceutical companies with additional support and expedited review from the FDA throughout the regulatory process. Despite much enthusiasm in the media regarding these developments, they should not be taken as a guarantee that either MDMA or psilocybin will be approved for clinical use. Although these declarations may appear to be enthusiastic endorsements of psychedelics by regulatory authorities, they should also be viewed in the spirit of equipoise.

Maintaining equipoise may be particularly challenging in the case of MDMA and psilocybin amid increasing public focus on these substances and, in some communities, a full embrace of psychedelic treatments. In particular, various social and political movements throughout the country are beginning to address the issue of clinical use of psychedelics. In Oregon, for example, a 2020 ballot initiative resulted in the legalization of psilocybin therapy and the mandate that the state create a regulatory framework under which a system of psychedelic mental health clinics will be developed. The Oregon policy stipulates that psilocybin may be provided for clinical purposes by nonprofessional “facilitators”—people without any professional background in mental health. Elsewhere, ballot initiatives that seek to decriminalize psilocybin and other psychedelics for both clinical and nonclinical uses have passed or are being planned. In this cultural landscape, psychiatrists should stay educated about the current state of psychedelic research and be mindful that phase 3 clinical trials on the use of psilocybin to treat major depressive disorder have yet to be published.

Oregon’s initiative risks undue extrapolation from the success of early clinical trials. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy’s positive results occurred in controlled research settings, with carefully screened patients and under the supervision of highly trained mental health professionals. Although these results are encouraging, evidence is not sufficient to suggest that safety and efficacy translate to uncontrolled settings with untrained facilitators who may not be equipped to manage complex and challenging clinical situations.

Psilocybin and MDMA remain Schedule I drugs at this time; however, the legal landscape may change if they receive regulatory approval. Researchers have recently reconsidered psilocybin’s legal status in accordance with its therapeutic potential and risk of abuse. One group of psychedelic researchers has suggested that psilocybin be made a Schedule IV substance, placing it in the same category as commonly used benzodiazepines (

13). The potential regulatory approval of MDMA and psilocybin for clinical use in the United States would entail rescheduling these substances to a less restrictive class and would mean that psychiatrists would be entitled to prescribe them, including for off-label use. We therefore recommend that psychedelics not be used in nonresearch settings until their safety and efficacy have been thoroughly demonstrated and standard practice guidelines have been developed.

Unique Methodological Challenges in Psychedelic Research

The ethics of psychedelic research are complicated by several unique features of the psychedelic experience. Both MDMA and psilocybin treatments are difficult to blind (for both researchers and participants). Because the effects of these substances are so acute, intense, and idiosyncratic, it can be relatively easy for participants and researchers to tell whether they have received a placebo or an active drug. Although various strategies have been developed to manage these challenges, the relative difficulty of making both patients and researchers blind to treatment type creates a situation in which bias may creep into assessments of patient outcomes and lead to inaccurate results.

Expectancy effects among research participants can also influence outcomes. Patients entering psychedelic clinical trials have likely read the headlines touting psychedelic therapies, creating high expectations for dramatic symptom relief. The cultural enthusiasm for psychedelics thereby risks causing a self-fulfilling cycle, in which high expectations lead to artificially inflated results (

19).

Researchers are still debating whether psychedelics affect core depressive symptomatology or whether improvements in symptoms occur in broader domains of personality functioning that ultimately have little to do with the neurovegetative symptoms of depression (

20). One study that has helped to address this concern involved a head-to-head trial of psilocybin versus a first-line antidepressant (

12). This study demonstrated parity between psilocybin and escitalopram on gold standard depression rating scales. Other unanswered questions include how often psychedelics can be safely administered when patients respond only partially to their first psychedelic treatment. The effects of repeated dosing and chronic use among patients who relapse or only partially respond to treatment remain unclear.

As previously stated, studies on MDMA and psilocybin have so far been conducted with carefully screened, highly restricted populations. The extent to which outcomes can be generalized from the carefully controlled setting of clinical trials remains unknown, placing people who receive these treatments at unnecessary risk for potential negative effects. Moreover, a majority of the participants in these trials have been White men. To enhance diversity and equity, more work needs to be done to engage marginalized populations in psychedelic research. Psychiatrists should be mindful about generalizing results of clinical trials to populations that have traditionally been excluded from research. Avoidance of generalization is particularly important with psychedelic therapies, in which cultural, economic, religious, and historical forces may play an outsized role in a patient’s experience. Researchers should emphasize the inclusion of all racial and ethnic groups in research and make additional efforts to include populations that have historically been underrepresented. The field of psychiatry should also make efforts to ensure that researchers and clinicians of all ethnic and racial backgrounds can participate in research, given that researchers’ personal histories can shape research priorities.

Finally, the comprehensiveness of psychedelic therapist training programs affects the outcome of clinical trials. In certain settings, psychotherapy training is intensive, often including more than 100 hours of specialized didactic and clinical experiences. If psychedelics are made available outside research settings, the quality of psychotherapeutic support may potentially fall as incentives to cut costs become more relevant. Psychedelic therapies should be flexible and tailor treatments to a patient’s specific needs. However, the unique and intense nature of the psychedelic experience, as well as the pharmacological complexity of these substances, requires that clinicians not compromise the quality and safety of psychedelic treatments should they become available.

Informed Consent: Unique Effects and Potential Risks of Psychedelic Treatments

The principle of autonomy requires that patients give adequate informed consent to psychiatrists for any psychiatric treatment. Distinctive features of psychedelic psychotherapies could in fact require what some have called

enhanced consent, a more comprehensive educational process about psychedelic therapies with the goal of ensuring that patients have a thorough understanding of the nature of these treatments (

21). These principles of consent apply in current research settings but would also be relevant in general clinical practice if psychedelics were to be approved for broader use. Protocols for obtaining informed consent for psychedelic therapies will be an important consideration in any future treatments. Such protocols are particularly important because psychedelic psychotherapies involve acute, intense changes in consciousness with which patients may have little prior experience. These changes can be profound and, especially in the case of classical psychedelics, may provoke high levels of anxiety. Psychiatrists should also consider the possibility that patients will have heightened expectations regarding the transformative effects of psychedelics and help patients adjust their expectations.

Psychiatrists in all settings should discuss with patients the potential changes to aspects of their personality, preferences, and beliefs that may result from psychedelic use. Research has indicated that psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy may produce enduring changes in people’s lives beyond a reduction in psychiatric symptomatology alone. Studies have indicated, for example, that the personality domain of openness may remain “significantly higher than baseline more than 1 year after the [psilocybin] session” (

22). Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy may have other broad effects, such as decreasing authoritarian political views and increasing one’s connection to nature (

23), changing religious orientation (

24), and affecting basic metaphysical beliefs (

25). Combined, these results have made some wonder whether psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy could affect basic aspects of patients’ identities—and whether these changes should be considered risks of psychedelic therapies. In light of these findings, an ongoing debate swirls about how these research findings apply to individual psychedelic users in clinical settings. The authors of several of these studies are careful to point out that their results were found among a select participant population and that overemphasizing these claims could lead to alarmism. In their view, “the current data simply do not support the idea that psychedelic treatments result in meaningful changes in political or religious beliefs or affiliation” (

26).

However strong the effects, changes such as these will be welcomed by certain patients, whereas others will be skeptical. Whatever an individual patient’s attitude, it is important that they be made aware of these possibilities before they provide consent. Patients concerned about undergoing such changes should have the ability to opt out of treatment before undergoing a psychedelic experience. The complexity of these considerations requires that the informed-consent process for psychedelic therapies be rigorous to ensure that patients have a sophisticated understanding of the therapies’ potentially wide-ranging effects.

The process of informed consent aligns with one of the core theoretical underpinnings of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapies: set and setting, the concept that the patient’s mindset (“set”) on entering the psychedelic experience as well as the environment (“setting”) in which the psychedelic experience occurs shape the tolerability, safety, efficacy, and quality of the experience. To maximize the chance that patients will have a valuable experience, psychedelic psychotherapy protocols attempt to optimize the patient’s mindset and the setting in which the psychedelic experience will take place. One important aspect of this process involves a period of psychotherapeutic preparation in the weeks before the dosing session. Typically, a patient meets multiple times with both the psychiatrist overseeing the trial and the therapists who support that patient during the session. The preparation stage is intended to help patients confront and manage challenges that may arise during the psychedelic experience. The preparation stage is built on principles of informed consent and also helps ensure that psychedelic psychotherapy is conducted ethically.

Protection of Patients Experiencing Challenging Psychological States

Psychedelic psychotherapy involves profound and acute changes in consciousness, which place patients in a uniquely vulnerable position. The classical psychedelics cause impaired working memory and executive function (

27) and facilitate openness and trust (

28). MDMA can likewise cause increased trust of and connectedness with others (

29). Although some of these effects can be benefits of psychedelics, they can make patients overtrusting, reducing their ability to recognize suspicious situations. Under the influence of psilocybin or MDMA, patients may become more suggestible and easier to manipulate. Patients may experience intense attachment and transference, including of a sexual nature. For these reasons, clinicians working with these substances must carefully uphold boundaries. Unfortunately, these boundaries have been violated by psychedelic therapists in the past, including those who initiated inappropriate and exploitative sexual, financial, and emotional relationships with patients (

30). The field of psychedelic psychotherapy should have no tolerance for such behaviors. As stated in the

APA Commentary on Ethics in Practice, “psychiatric patients may be especially vulnerable to undue influences and the psychiatrist should be sensitive and careful that [their] conduct does not physically, sexually, psychologically, spiritually or financially exploit or harm the patient” (

31). This commitment is particularly important for patients having psychedelic experiences and should feature prominently in the training of any clinician interested in psychedelic therapies.

Beyond the dosing session itself, patients are also vulnerable to long-term negative outcomes of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapies. Although epidemiological surveys have demonstrated no population-level link between classical psychedelic use and poor mental health outcomes (

32), patients may have individual risk factors that place them at elevated risk. To address the concern that psychedelics may precipitate psychosis, clinical trials on psilocybin and MDMA typically use a personal or family history of psychosis as an exclusion criterion. These risks suggest the need for psychiatrists to be judicious when providing psychedelic therapies. Patients should be carefully screened for low-grade psychotic symptoms and a potentially high-risk vulnerability to negative outcomes. Beyond psychosis, researchers have begun to investigate which factors predict a negative response to psychedelics (

33,

34). Ultimately, however, this area still has large gaps in understanding, which could place patients with unknown risks in a vulnerable position. Psychedelics are not effective or desirable for everyone, and psychiatrists should attempt to identify patients who are particularly vulnerable to negative outcomes before suggesting that those patients undergo a psychedelic experience.

Off-Label Psychedelic Use and Psychedelic Self-Improvement

If psychedelics are approved for general psychiatric use, psychiatrists will likely encounter patients who seek psychedelic therapies. The so-called psychedelic renaissance is in part fueled by people pursuing personal changes and self-improvement in the absence of obvious psychiatric problems. People are increasingly turning to psychedelics in the midst of major life decisions such as relationship or career changes, to establish a deeper connection with nature, or to enhance creativity and productivity. Another possibility in the realm of psychedelic self-improvement is the substances’ proposed use as agents of “moral enhancement” (

35).

Psychiatrists should be mindful that all prescription medications, including psychedelics, should only be prescribed to treat diagnosable psychiatric disorders. When patients come to the clinic, they should be carefully screened for any underlying psychopathology. If no clinical indication is found, psychiatrists should avoid prescribing psychedelics, just as they would for any other medication. Psychiatrists should be particularly careful to avoid offering psychedelics to people looking for a recreational experience. Although these are straightforward and routine principles of prescribing, they may appear more complicated in the case of psychedelics. Because of psychedelics’ potential for promoting self-improvement in the domains described earlier, psychiatrists may be inclined to prescribe them for such nonclinical purposes.

Psychedelics’ broad applications may make it difficult for psychiatrists to determine where treatment ends and enhancement begins. The case of stimulants, which are effective treatments when prescribed judiciously for clinically indicated conditions but are frequently misused or overused for cognitive enhancement, is instructive (

36). Psychiatrists offering psychedelic treatments should be careful to avoid a situation parallel to that of stimulants by limiting psychedelic prescriptions to patients with clear clinical indications.

On one hand, if patients’ goals for psychedelic use are related to diagnosable mood, anxiety, trauma, or personality disorders, clinical judgment may support the off-label use of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. On the other hand, psychiatrists should avoid offering psychedelics to people seeking a competitive productivity boost. Given the possibility that the demand for psychedelics will outstrip the supply of clinical providers, it is a matter of equity to reserve treatment for those who have a mental health condition. Ultimately, the psychiatrist is responsible for understanding the causes of a patient’s challenges and why they have been unable to realize improvements with interventions other than psychedelics. The psychiatrist should form a treatment plan only after symptoms and their relationship to functioning have been thoroughly explored.

Moreover, psychiatrists should be mindful that little evidence currently exists to support psychedelic use for most clinical indications. Fortunately, ongoing research may one day help guide clinicians’ use of psychedelics for a broader range of conditions. Psychedelics’ efficacy in treating personality disorders, for example, remains an open question, although some research has begun to study LSD and psilocybin for this indication (

37,

38). The use of psychedelics to treat anxiety disorders is also a burgeoning area of research (

8).

If psychedelics become accessible to the general psychiatric population, psychiatrists should also avoid overreliance on them. Treatment plans should be comprehensive and tailored to each patient. Psychiatrists should avoid a mindset in which all problems can be solved with psychedelics. Because of their potential applications for nonclinical self-improvement, psychedelics pose a risk of pathologizing everyday challenges of life, leading to an untenable situation in which any stressful event justifies psychedelic intervention. Psychiatrists must recognize that psychedelics are one tool in the toolbox and prudently deploy them when, in their clinical judgment, a patient’s challenges are likely to be responsive to psychedelic interventions. Some concern has been expressed about the irresponsible use of ketamine in clinics, a precedent that should be carefully avoided if other psychedelic treatments become accessible (

39). The combined risks of excessive exuberance and overpathologization also have precedent in the case of medical cannabis, where patients gain ready access to cannabis for purposes for which the evidence base is limited (

40). These risk factors can jeopardize the integrity of the psychiatric profession and could ultimately decrease public trust in psychiatry.

Differences Between Clinical and Nonclinical Psychedelic Uses

Although MDMA and psilocybin are not yet available for clinical use outside research settings, psychiatrists may already be hearing from patients who are interested in using psychedelics outside clinical settings and who seek their psychiatrist’s advice on various aspects of psychedelic use. This phenomenon poses unique challenges to psychiatrists. Psychedelics are highly visible in the media and the culture at large. Unlike other experimental treatments, they are relatively easy for savvy patients to access. Faced with patients who express their intention to procure and use psychedelics in a naturalistic setting (whether for treatment of mental illness, self-improvement, or recreation), psychiatrists may confront the ethical dilemma of how to advise them.

Psychiatrists should feel comfortable having these discussions with their patients, despite the complicated ethical balancing act required in such conversations. First, psychiatrists should be clear that although clinical trials are promising, these medications are still in the experimental stage, and final determination of safety and efficacy rests in the hands of regulatory agencies such as the FDA. Psychiatrists may also reinforce the difference between psychedelic use in a clinical setting, where clear protocols are in place to ensure patient safety, and in a naturalistic setting, where efficacy and safety are less assured. This distinction is informed by the principle of set and setting—the idea that a safe clinical setting may affect the outcome of the psychedelic experience and that the experience may be less predictable and carry greater risk when a patient is using psychedelics on their own, without the guidance of trained professionals. Psychiatrists may also determine that a patient could benefit from a psychedelic clinical trial and make appropriate referrals to research institutions.

Psychiatrists should communicate that patients take on additional risks when they pursue psychedelic use outside clinical settings. The act of procuring psychedelics can involve violence, intimidation, theft, and contact with organizations that perpetrate crime and endanger public safety. Once a substance has been obtained, patients may not be able to accurately identify what they have procured. Products sold as pure MDMA, psilocybin, or LSD may be adulterated with other unidentified substances, which can increase the risk for toxicity. Drug-checking services, which chemically analyze drug samples to determine which substances are present, are increasingly in demand at music festivals, where the use of psychedelics and other recreational drugs is popular (

41,

42). Outside certain settings such as festivals, however, it can be difficult to confirm the identity of a substance. These issues are complicated by the increasing prevalence of new psychoactive substances: synthetic compounds that mimic the effects of drugs, including psychedelics, but often carry additional effects and risks that may be unknown to the user.

Moreover, psychedelic users may be unable to manage the adverse effects of psychedelics on their own, placing them at elevated risk for severe outcomes. In particular, MDMA is associated with an elevated rate of adverse effects and death when taken in a nonclinical setting. In one study of four countries over two decades, researchers identified 1,400 MDMA-related deaths (

43). Although a majority of these deaths were associated with multiple drug toxicities, 13%–25% of the deaths were attributed to MDMA alone. Psilocybin, however, has been associated with death only in extremely rare circumstances, and even these rare cases have been contested within the research community (

44). The possibility of death from toxicity is therefore a crucial point of difference in the risk profiles of MDMA and psilocybin. Nevertheless, the risks of adulteration, the possible dangers of procurement of substances, and the increasing prevalence of new psychoactive substances apply to psilocybin as well. For these reasons, psychiatrists should clearly communicate to patients that nonclinical use of psychedelics could be dangerous.

Psychiatrists should also be particularly cautious with adolescents who indicate their desire to use psychedelics in a nonclinical setting. The risks of psychedelic use among adolescents may be heightened relative to adults’ risks. Adolescents taking psychedelics may experience stronger reinforcing or aversive effects (

45). Moreover, adolescents may be more likely than adults to engage in risky behaviors while under the influence of psychedelics.

Some patients are likely to pursue psychedelics despite their psychiatrist’s concerns—and they may seek input from their psychiatrist even after the psychiatrist has raised their concerns (

46). In addition to the transferential implications of such requests, psychiatrists may also need to consider how to manage a patient’s psychotropic medications. Psychiatrists should educate patients on the potential (and in many cases unknown) risk of interactions between psychedelics and common psychotropic medications. Some preliminary research has indicated that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may attenuate the effects of LSD (

47), and anecdotes and older case studies have documented more severe and sometimes fatal effects from combining other psychotropic medications with MDMA (

48,

49). Given these risks, psychiatrists may consider tapering medication in preparation for a patient’s self-directed psychedelic experience and whether to restart medications afterward—both steps that are typically followed in clinical trials. Psychiatrists should consider adopting harm-reduction approaches to minimize the risks to their patients. Psychiatrists should take an active, exploratory, and nonjudgmental role in helping a patient understand the risks of their decision and should think through how to manage medications if a patient is committed to using psychedelics on their own.

Given psychedelics’ complicated history and psychiatrists’ often strong opinions about them—positive or negative—it will be important for psychiatrists to be mindful of any personal bias and its impact on clinical decision making. In cases in which bias is present, it may be difficult for psychiatrists to act with patients’ best interests in mind. In such situations, psychiatrists should be aware of their bias and consider referring patients to other providers if they cannot overcome it. However, opinions on psychedelics should not automatically be relegated to the status of bias. These treatments involve complicated issues, and thoughtful deliberation about their place in psychiatry will be required. An open, honest discussion about their role will be essential to determine how they can be most effectively and safely used. Such conversations will take place not only among psychiatrists but also between psychiatrists, patients and their families, and other mental health advocates.

Challenges to Psychedelics’ Scalability and Broad Adoption Among Diverse Communities

As with any new treatment, psychedelics raise concerns about who can access them and how affordable they will be. As research and clinical applications expand, efforts should be made to ensure that these interventions can be accessed by all members of society who may benefit from them and are not reserved for a select few. The history of psychedelics is relevant to matters of access: Indigenous groups have been using psychedelics in religious and medicinal settings for millennia. In the event that psychedelics become incorporated into the psychiatric mainstream, many have commented on the importance of honoring the communities who, over the course of generations, developed the principles of psychedelic use (

50). As modern psychedelic research progresses, it is important to distinguish ceremonial use of psychedelics such as peyote, which was legalized by the U.S. federal government for use in the Native American Church in 1994, from the medical use of psychedelics (

51). Concern also exists that modern medical settings will attempt to mimic the ceremonial practices and symbols of Indigenous people in ways that devalue these rich traditions.

It is crucial that marginalized communities have access to psychedelic therapies, both in research settings and (if they become available) for general clinical use. Research has indicated that White individuals account for more than 80% of study participants in psychedelic trials to date (

52). Psychiatrists should make efforts to ensure that patients from all backgrounds, particularly those who have historically been excluded from psychiatry, are able to access treatment. Moreover, the field of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy should pay careful attention to cultural humility and social determinants of mental health. Psychiatrists should actively involve marginalized communities in psychedelic research and, if the treatments become approved by the FDA, should include these communities in discussions on how to best ensure they can access treatment.

Logistics of the psychedelic experience also affect issues of equity and access. In particular, the cost-effectiveness of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, whether with MDMA or psilocybin, poses challenges for scalability. For example, on the day of dosing, patients require oversight by trained therapists for up to 8 hours. Many trials so far have required two graduate-level therapists and a psychiatrist to be present for the full duration (often 8 hours) of a single patient’s dosing session. Some trials have also required participants to have an overnight stay after their dosing session. Costs are further elevated by the need for private space that can be occupied for the duration of the dosing session. In addition, one must account for the cost of several hours of psychotherapy and psychiatric evaluation in both the preparation and integration phases.

These factors make psychedelic therapies more resource intensive than many other psychiatric interventions, raising the question of how they will be economically viable outside the realm of clinical trials—and whether public and private insurances will cover the treatments for use among the general population. Consequently, high-quality psychedelic therapy will remain inaccessible for those unable to afford it. Another potential pitfall is the scenario in which the quality of psychotherapeutic support is sacrificed to meet the demand of patients seeking psychedelic treatments. Such factors raise ethical questions related to justice and the ability of people from all socioeconomic and racial-ethnic backgrounds to benefit equally from new treatments.

Fortunately, efforts are under way to explore potentially cost-saving and access-promoting approaches such as group psychedelic therapy and short-acting psychedelics (

53,

54). Other strategies that may improve access include the use of nonhallucinatory psychedelics and microdosing, in which subperceptual doses of psychedelics are consumed on a recurring basis. Both of these approaches have yet to be rigorously studied, although clinical trials are currently being planned or are under way (

55,

56).

Scalability issues raise questions about when psychedelic therapies should be offered in the course of a patient’s illness. Although some general treatment guidelines exist, no universal algorithms dictate precisely which intervention should be used. Where psilocybin, MDMA, and other psychedelics fit in psychiatric treatment is an important consideration as research progresses. The ability of people from all backgrounds to access psychedelic treatments will factor prominently in determining psychedelics' future role in psychiatry.