The managed behavioral health care industry began in the mid-1980s as a reaction to increased costs resulting from the growing inclusion of mental health and substance abuse benefits in private insurance plans. As health plans, insurance companies, self-funded plans (Employer Retirement Income Security plans), and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) began to offer managed care products for behavioral health, managed behavioral health organizations emerged to manage these benefits by setting up and administering behavioral health provider networks (

1).

Enrollment in managed behavioral health care programs has grown steadily, from 78.1 million in 1992 to an estimated 124 million in 1996 (

1). Of the estimated 181.4 million people with health insurance in 1996, a total of 68.4 percent were enrolled in some type of specialty managed behavioral health organization (

2). Most organizations are large for-profit companies that operate across different types of employers and geographic areas. The industry is dominated by a small number of large firms, and their networks and operations may function differently from place to place (

3).

Behavioral health care services may be embedded, as are other services, in the general delivery system of a health plan, they may be provided through a distinct and separate structure, or they may be offered in a hybrid way involving elements of both approaches (

4). The term managed behavioral health care encompasses a variety of programs and technological applications. Types of products include administrative services only, utilization review, employee assistance programs, integrated management, and full-risk arrangements. The role of a managed behavioral health care organization differs markedly across these products. Arrangements vary in their intensity of care management, levels of risk, and amount of revenue, ranging from the purely administrative service and provider network model at one extreme to the full-risk capitated product at the other (

5).

Despite the growing enrollment in managed behavioral health care arrangements, relatively little is known about the characteristics of the organizations and the scope of services. Kihlstrom (

6) acknowledged that little information about managed behavioral health care firms is available through the major associations, and because many of the firms are not traded publicly, much of the information is proprietary.

Data for Kihlstrom's study were obtained through national surveys conducted by the staff of Business Insurance and compiled into directories as a service to employers. For the 106 managed behavioral health care organizations that could be tracked using the directories, during the period from 1990 to 1994, the median age of the firms was 12 years. Eighty-four percent of the firms were for profit, and 70 percent had parent companies that were insurance companies or larger more general for-profit managed care companies. Kihlstrom groups the services offered by managed behavioral health care organizations into four broad categories: assessment-treatment, health promotion, education-general, and utilization review. Health promotion was offered by only about a third of the companies.

Kihlstrom also analyzed the scope of operations for the 106 firms, providing numbers of staff and clients (covered lives), size of geographic service areas, and an index of the company's growth. The median number of professionals with whom managed behavioral health care firms contracted increased from 64 to 251 between 1990 and 1994. The median number of clients was 100,000 in 1990 and 71,659 in 1994. The median number of states in which the firms conducted business grew from 16 in 1990 to 29 in 1994.

The data reported here were gathered directly from managed behavioral health organizations in 1997 by the American Managed Behavioral Healthcare Association (AMBHA). The data provide a somewhat more detailed look at the characteristics of these organizations for calendar year 1996. AMBHA was founded in 1994 to enable organizations in this new industry to work together on key issues of public accountability, quality, public policy, and communication. Current membership includes nine national and regional organizations that manage behavioral health care for more than 100 million subscribers.

Methods

The survey was conducted by Milliman & Robertson, Inc., an international consulting firm with actuarial and risk management expertise, in cooperation with Open Minds, a research and consulting firm specializing in behavioral health and human services. The 14 participating organizations represent a total of 20 million covered lives, making this the first time detailed information has been collected from managed behavioral health care organizations representing such a large segment of the population. The market shares of the 14 organizations range from large to small, and some firms appeared on the list published in the

Open Minds newsletter of those with the largest market share in 1997 (

2).

The AMBHA survey instrument was mailed to 56 managed behavioral health care organizations early in 1997. Topics covered by the survey included organizational characteristics, benefits and benefit limits, and service utilization. Of the 56 organizations to which the survey was sent, 14 completed the survey instrument either totally or in part. Six of the 14 provided a complete response to all sections. This paper reports data from these six organizations.

The six organizations in this core group vary in size of market share and include several of the organizations that had larger shares at the time of the survey. They represent a total of more than 16 million covered lives and account for approximately 13 percent of all individuals enrolled in managed behavioral health care organizations in 1996, the largest sample for which such data are available.

The relatively low response rate to the survey may be attributed to a number of factors. First, data for these organizations are proprietary, and organizations may have been reluctant to participate in the survey because of the highly competitive nature of the industry. Further, a number of the organizations voiced strong concerns about divulging or sharing data because of an ongoing antitrust lawsuit against several firms. Another potential reason is variability in the development of management information systems—many of the organizations were quite new at the time and had not yet developed their information management systems sufficiently to permit them to generate the requested data.

The survey solicited information about benefit design characteristics for each organization's ten largest contracts or those with the greatest number of covered lives. Information was requested about limits on inpatient days and outpatient visits per calendar year, limits on dollar amounts per calendar year, lifetime limits on dollar amounts, percent of coinsurance, amount of copayment, calendar year deductibles, limits on out-of-pocket expenditures, coverage for chronic conditions, and any conditions excluded from coverage.

Similar products were grouped to eliminate minor differences in benefit design. For example, plans with calendar year deductibles of $400, $500, and $600 were combined into the results provided for the $500 deductible plan. For each benefit characteristic, the range as well as the most common limitation or characteristic (mode) is reported.

Respondents provided data on the number of contracts, the total number of enrolled members, and revenues during calendar year 1996, by source of revenue or by product type. The conceptual framework for the survey separated results into network-based products, stand-alone products involving employee assistance programs, products that integrate networks and employee assistance programs, and utilization review-based products (nonnetwork products).

These categories were further split between risk and nonrisk products. Risk products were fully capitated arrangements, in which the managed behavioral health organization is liable for both inpatient and outpatient benefits as well as case management and other administrative expenses. Employee assistance programs that include coverage of therapist visits as part of the fees paid by the contract holder to the managed behavioral health organization were categorized as risk contracts.

Nonrisk products were agreements for administrative services only, in which the managed behavioral health organization is responsible only for case management and other administrative expenses. Employee assistance programs that do not cover therapist visits as part of the fees paid by the contract holder to the managed behavioral health organization were characterized as nonrisk contracts.

Information was also provided by payer type, which included private employers, HMOs, federal employers, state employers, other public employers, Medicaid, Medicare, and all other payers.

Results

Contracts, covered members, and revenues

The six core respondents reported a total of 44,186 contracts. The vast majority of contracts (43,983, or 99.5 percent) were with private employers. Ninety-nine contracts were with HMOs, 51 with other public employers, 18 with Medicaid, ten with Medicare, nine with state employers, nine with other types of payers, and seven with federal employers.

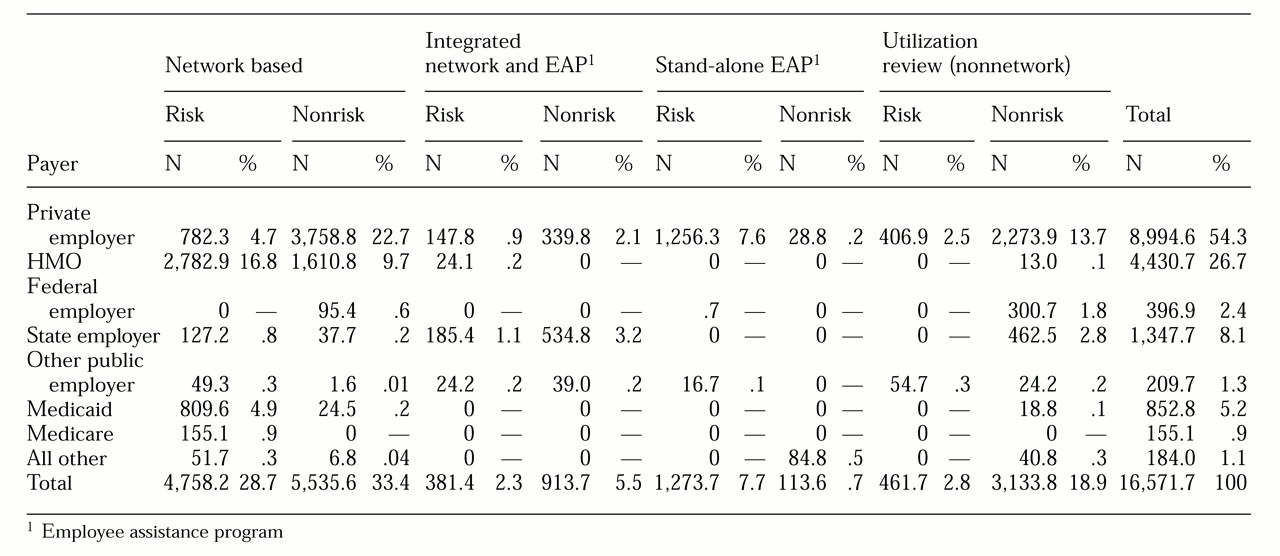

Table 1 summarizes information about the enrollees in the six core organizations by payer type. The organizations represented a combined total of 16,571,667 covered lives or members. Although the vast majority of contracts were with private employers, the number of members covered under contracts with private employers represented 54.3 percent of the total. Contracts with HMOs covered 26.7 percent of total members.

Almost two-thirds of the enrollees were covered by contracts in the network-based category, including both risk and non-risk products.

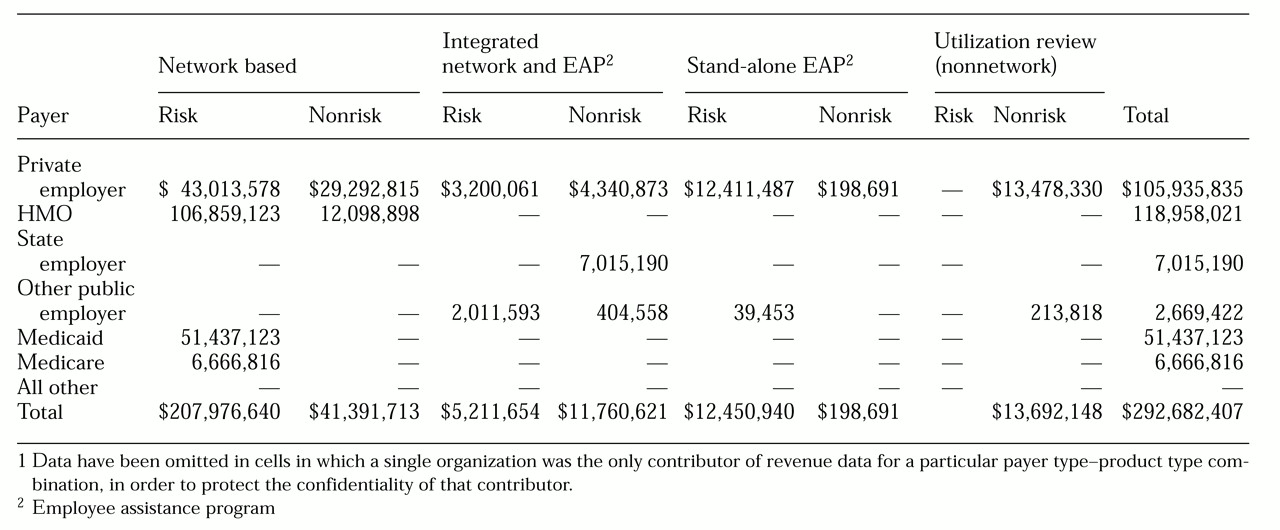

Table 2 presents data on revenues by payer type. Revenues reported by the six participants totaled $292,682,407. The network-based risk product category, which represented 28.7 percent of covered members, represented 71.1 percent of revenues. Contracts with private employers, HMOs, and Medicaid together accounted for 94.4 percent of the revenues. When both payer type and product type are considered, HMO network-based risk contracts accounted for 36.5 percent of revenues.

Benefit characteristics and limits

Calendar year deductibles for all behavioral benefits ranged from $0 to $500 for private employers, $0 to $500 for HMOs, $0 to $600 for state employers, and $0 to $450 for other public employers. The most common plan design—the mode—for all types of payers was a calendar year deductible of $0. Lifetime limits ranged from $15,000 to no limit for private employers and HMOs, and from $50,000 to no limit for state employers; the mode for all payers was no limit.

Across all payer types, the most common coverage for acute inpatient facilities was a limit of 30 days per calendar year. The 30-day limit was also the mode for residential facilities, with the exception of contracts with other public employers, for which the mode was 45 days. For inpatient and residential facilities, contracts with private employers most commonly required a copayment of 20 percent; for state employers, it was 10 percent; and for contracts with HMOs and other public employers, the most common copayment was 0 percent.

However, contracts with HMOs tended to place greater restrictions on outpatient psychotherapy and medication management visits than did other types of payers. The most common calendar year limit for HMO contracts was 20 outpatient visits a year, compared with 50 visits a year for the other payer categories. Contracts with HMOs also had higher copayments for outpatient psychotherapy and medication management visits. The most common outpatient copayment was $20, compared with $10 for contracts with private and state employers and $0 for other public employers.

The survey also requested information about coverage for chronic conditions and benefit exclusions. Chronic conditions most typically covered were schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, paranoia, bipolar affective disorder, major depression, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Conditions commonly excluded were mental retardation, chronic organic brain syndrome, Alzheimer's disease, learning disabilities, medically based conditions, problems listed among DSM-IVV codes, autism, and court-ordered cases.

Limited information about employee assistance programs was also gathered through the survey. The six respondents reported that these products ranged from three-session models to eight-session models and that most required no deductibles or copayments for psychotherapy sessions. However, one plan required a $15 copayment for sessions beyond the fifth visit.

Delivery system characteristics

Categories of inpatient services included in the survey were inpatient mental health care, inpatient substance abuse treatment, partial hospitalization for mental health treatment, partial hospitalization for substance abuse treatment, intensive outpatient mental health care, intensive outpatient substance abuse treatment, residential care, 23-hour-bed interventions, and a category for all other services.

Outpatient services were defined as inpatient visits (visits by professionals to hospitalized clients), diagnostic visits, psychotherapy, medication management, and a category for all other visits. Types of professionals were psychiatrists, addiction physicians, other physicians, doctoral-level psychologists, master's-level social workers, other master's-level clinicians, registered nurses, and a category for all other professionals.

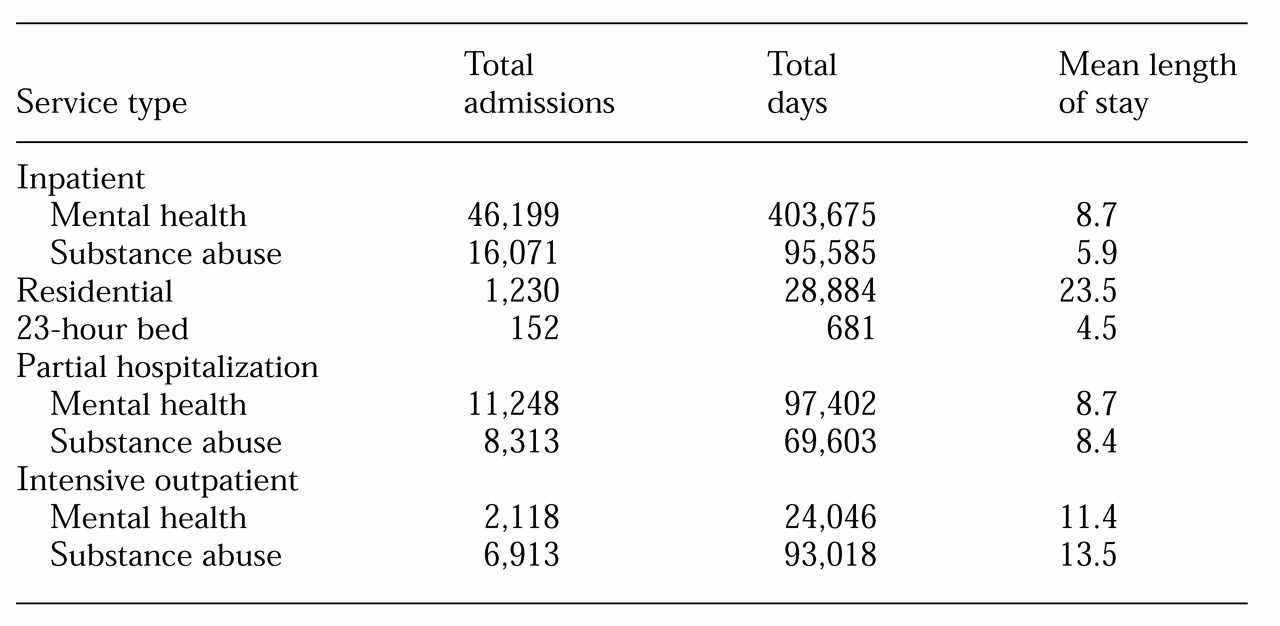

Table 3 presents data on use of inpatient services. A total of 92,244 admissions to mental health and substance abuse facilities were reported. The mean length of stay for inpatient mental health admissions was 8.7 days. Admissions to partial hospitalization facilities for mental health care, a relatively intensive and structured service that provides up to nine hours a day for five days a week, totaled 11,248, and the mean length of stay was 8.7 days. Respondents reported 2,118 admissions for intensive outpatient mental health services, a structured but more limited program, involving two to three hours of service a day, several days a week; the mean length of stay was 11.4 days.

For substance abuse inpatient facilities, 16,071 admissions were reported; the mean length of stay was 5.9 days, which was shorter than for mental health inpatient facilities. A total of 6,913 admissions were to intensive outpatient substance abuse facilities, and the mean length of stay was 13.5 days. The utilization rate for intensive outpatient substance abuse services was higher than that for this type of mental health services and the stays were also longer.

A total of 1,230 admissions to residential facilities were reported, with a mean length of stay of 23.5 days. The survey did not distinguish between residential mental health and substance abuse facilities.

The six organizations reported a total of 2,231,664 outpatient visits. Visits to master's-level social workers represented 33.3 percent of total visits, with an average of 157 visits per provider per year. Visits to psychiatrists accounted for 20.5 percent of the total, with an average of 160 visits per psychiatrist per year. Visits to doctoral-level psychologists accounted for 20.2 percent, with an average of 84 visits per psychologist per year. The category all other professionals represented one-third of all professionals but accounted for only 12.4 percent of visits.

Utilization of services

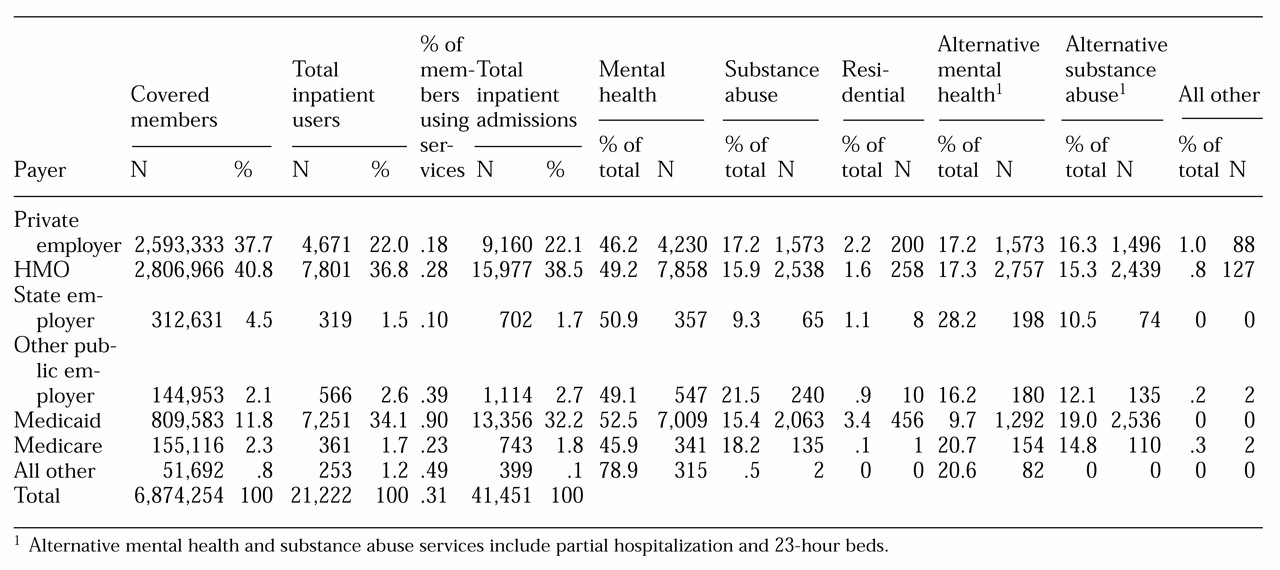

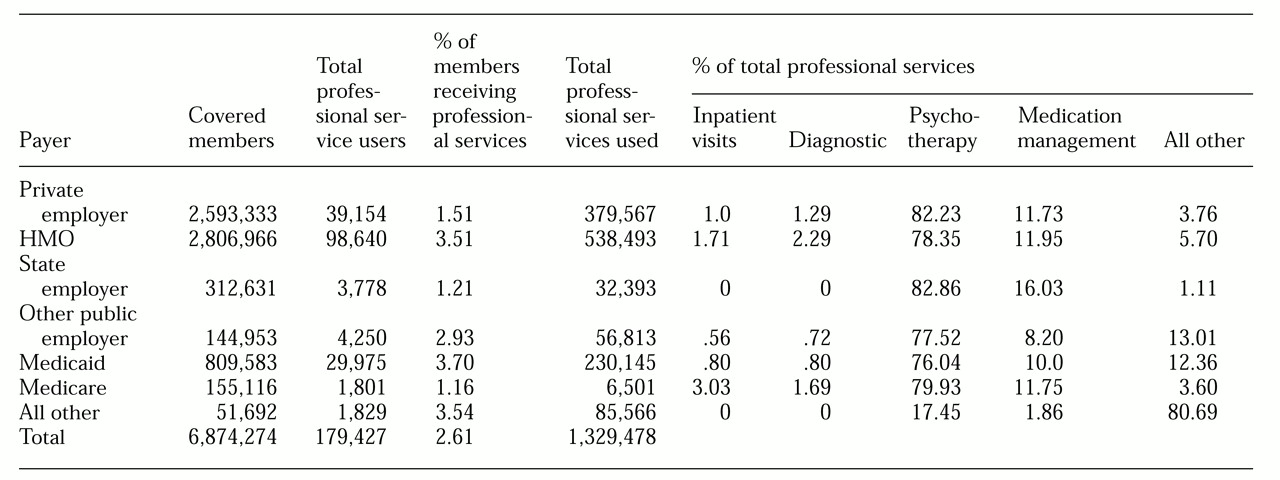

Table 4 presents data on use of inpatient services by payer type, which was reported for risk-based contracts only. A total of 6,874,274 covered members were represented. Of this subset, .3 percent (21,222 members) used some type of facility services during 1996. The percentage of members using inpatient facility services ranged from .1 percent for contracts with state employers to .9 percent for users covered by Medicaid.

Table 5 summarizes information on use of different types of outpatient services by payer type. Approximately 2.6 percent of the 6,874,274 covered members used outpatient services in calendar year 1996. Among contracts with private employers, 1.51 percent of covered members used outpatient services. In contrast, 3.7 percent of individuals covered by Medicaid contracts received outpatient services. Psychotherapy accounted for the highest proportion—between 76 and 83 percent across all payer types, excluding "all other payers." Medication management was the next highest—between 8.2 percent and 16 percent. Diagnostic services, visits to inpatients, and all other types of services represented 1 percent to 13 percent of total outpatient services.

Discussion and conclusions

We have reported on the characteristics of six managed behavioral health care organizations during calendar year 1996. Although these data are limited in scope, they represent a substantial number of covered lives and provide more detail than has previously been available about the characteristics of managed behavioral health firms. The companies provided data on more than 16.5 million members through 44,186 contracts with private employers, HMOs, federal and state employers, other public employers, Medicaid, Medicare, and others. This number represents about 13.3 percent of all persons who were enrolled in managed behavioral health care in 1996.

The vast majority of these contracts were with private employers, and the majority of members were covered under contracts with private employers or with HMOs. Data on benefit limits presented here are consistent with the findings of other surveys, such as behavioral health data gathered through the Mercer/Foster Higgins National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans (

7). Both of these surveys found that, across all payer types, the most common coverage for inpatient facilities was limited to 30 days per calendar year. Both also reported that contracts with HMOs tended to place greater restrictions on outpatient visits than did other types of payers. Both surveys found that the most common calendar year limit for HMOs was 20 outpatient visits per year, compared with 50 visits per year for the other payer categories in the American Managed Behavioral Healthcare Organization survey, and 30 to 40 visits per year in the Mercer survey. However, our survey is limited in that it does not report the proportion of contracts or payers that actually provided coverage for a particular service.

The data reported here suggest variations in patterns of service use across different payer types. Service use appeared consistently higher among members covered by Medicaid. Only .18 percent of members covered by private employers used inpatient facility services, and 1.5 percent used outpatient services. However, for members covered under Medicaid, these percentages were .9 percent and 3.7 percent, respectively. Admissions to residential facilities represented 3.4 percent of total admissions for Medicaid-covered individuals, compared with 2.2 percent for private employers and 1.6 percent for HMOs. Average length of stay in residential facilities for Medicaid-covered members was 34 days, compared with 25 days for state employers, 11 days for private employers, and 6.5 days for HMOs.

Rates of service utilization (also called treated prevalence) reported here are somewhat lower than those reported in the recent literature, both before and after managed care. A recent report from the National Institute of Mental Health (

8) stated, "Epidemiologic data from the period before managed behavioral health care became widespread provide a baseline for determining how managed care has affected access to mental health services. According to data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey in the late 1980s and the National Comorbidity Study (NCS) in the early 1990s, between 5.8 percent (NCS) and 5.9 percent (ECA) of U.S. adults used specialty mental health services in one year. A national multisite study of specialty mental health service use by children (ages 9 to 17) conducted in the early 1990s reports an 8.1 percent treated prevalence rate."

According to the NIMH report, "Although no comparable national prevalence data for adults and children are available for the current era of managed care, recent studies reveal wide variability in treated prevalence, ranging from .9 percent to 9.7 percent of members using outpatient specialty mental health services. Even within a single managed care organization, outpatient treated prevalence varied fivefold, from .9 percent to 4.9 percent in a small number of commercial contracts."

The utilization rate for outpatient services in our survey was reported to be 2.6 percent across all covered members; it ranged from a low of 1.16 percent for contracts with Medicare to 3.51 percent for HMOs and 3.7 percent for Medicaid contracts. Utilization of inpatient services was reported to be .3 percent for all covered members, ranging from a low of .1 percent for contracts with state employers and .18 percent for private employers to a high of .9 percent for users covered under Medicaid.

The task of collecting and analyzing data to characterize managed behavioral health care organizations is complicated by the fact that this area of managed care is rapidly evolving. Numerous mergers and acquisitions make it difficult to obtain comparable data for longitudinal analysis. As Mihalik and Scherer (

9) have pointed out, the entire managed care field is in a state of flux as it responds to legislative changes, provider and consumer activism, and, in particular, market forces. The way in which managed behavioral health organizations address these challenges has led to many variations in organizational structure, payment mechanisms, and utilization management systems. The data presented here provide a starting point that may serve to guide further investigation in this area.