Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is a federal, means-tested welfare program for individuals who are poor, blind, disabled, or aged. In March 1996, Congress passed Public Law 104-121, which eliminated substance abuse as a basis for granting disability benefits under the SSI program. Individuals whose benefits were terminated by the legislation lost monthly cash payments and health insurance coverage under Medicaid as of January 1, 1997.

Beneficiaries under a substance abuse disability were allowed to appeal the termination decision and to apply for reclassification under another disability status. Nationwide, 64 percent of these individuals applied for reclassification; 35 percent were reclassified and continued to receive benefits (

1). Those who were reclassified retained their cash benefits and health insurance, but they were no longer required to be in substance abuse treatment or to have a representative payee as a condition for receiving benefits, as they had been previously. Individuals who were not reclassified could apply for public income assistance from the state or the county.

The results of earlier studies suggest that individuals who received SSI benefits for a substance abuse disability had substantial medical and psychiatric health problems that were independent of their alcohol and drug use (

2). Many SSI beneficiaries who reported mental health problems lost benefits under the new law, either because they did not appeal or because their appeal was denied (

3,

4). Little is known, however, about the effect of terminating income assistance and health insurance on the mental health and health care utilization of a population that is both poor and has substance abuse problems. It might be expected that the loss of these benefits would lead to increased psychosocial stress and decreased financial ability to obtain care, which in turn may have a negative effect on mental health.

In this article, we report the results of a longitudinal cohort study of individuals in Los Angeles County who were receiving SSI benefits for a substance abuse disability at the time of the federal policy change. We describe the subjects' probable mental health diagnoses at the time of the legislation and note any changes in their mental health status and use of mental health services two years after the policy change. Because deterioration in mental health status may be more pronounced among individuals who have a preexisting mental health condition, we stratified our sample by probable mental health diagnosis at baseline.

Methods

We randomly selected 400 people from the Social Security Administration's October 1996 roll who were receiving SSI benefits for a substance abuse disability. Of these, ten persons were confirmed deceased, one was misclassified, and 52 could not be located. Individuals were excluded from the study if they were under 21 or over 60 years of age, if they resided outside of Los Angeles County (four individuals), if they had a legal guardian (one individual), or if they were also receiving Social Security Disability Insurance. Twenty-four individuals refused to be interviewed. A total of 308 individuals were interviewed at baseline, for a response rate of 79 percent, adjusting for the ten persons who were confirmed deceased and the one who was misclassified.

Baseline interviews were conducted between December 1996 and April 1997, and follow-up interviews were conducted every six months over a two-year period. Most of the interviews were face-to-face, and they took place at the Drug Abuse Research Center at UCLA or in the community. The interviewers received three days of training and were evaluated by supervisors before beginning the fieldwork. The interviews were designed to collect information about the subjects' demographic characteristics, mental and physical health, substance abuse and treatment status, use of health care services, employment, income, and criminal activity.

Measures

Source of income. We used longitudinal data to classify respondents by whether they continued to receive SSI benefits under a different classification; whether they depended primarily on other forms of public income assistance (for example, the state/county General Assistance program); or whether they did not rely on public income assistance. Individuals in this latter group relied primarily on nonpublic sources of income such as employment, friends, family, or illegal activity. The respondents' source of income was first classified at each interview wave. Individuals who reported receiving SSI payments for either the past 30 days or for three out of the past six months were classified as receiving SSI payments for that wave. Of the remaining participants, those who reported receiving income from other public sources for either the past 30 days or for three of the past six months were classified as receiving public income assistance; the remainder were classified as not relying on public income assistance for that wave.

Participants were then assigned to an income source status on the basis of their reported source of income for the majority of the waves. When there was no majority, we classified the respondents according to their source of income at the 24-month follow-up. A total of 106 individuals (42 percent) continued to receive SSI benefits on the basis of another disability, 68 (27 percent) replaced lost SSI benefits through other forms of public assistance, and 79 (31 percent) did not rely on public income assistance.

Mental health. We characterized mental health on four dimensions: self-reported diagnosis, perceived emotional health status, current symptoms and problem severity, and disability. Participants were asked whether they had any severe and persistent emotional problems, what the problems were, and what medications they had ever taken for each problem. Using this information, we categorized the participants as having no identified mental disorder, having a situational problem or "stress," having a probable depressive or anxiety disorder, or having a probable psychotic or bipolar disorder. Because many of the subjects were not in treatment—and cost constraints precluded a clinical interview—we were unable to confirm our diagnostic categorizations with professionally determined diagnoses.

We defined emotional health status as the percentage of participants who reported poor or fair emotional health. The psychiatric composite score of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) was used as a current measure of symptom and problem severity (

5). The ASI score is a weighted combination of scores on 11 questions about current symptoms, current psychotropic medication, and perceived need for treatment. Composite scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The ASI has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of problem severity (

6,

7), although its use with individuals who are severely mentally ill has been questioned (

8,

9). However, the results of earlier studies suggest that most of the individuals in our sample did not have a severe mental illness (

10).

Participants' disability or functioning was assessed by the number of bed-days or restricted activity days they had experienced in the past month because of an emotional problem. There was substantial agreement between the measures of emotional health, with Pearson's correlation coefficients greater than .48 for the continuous variables and χ2 values significant at p values of .001 or less for the categorical variables.

The sample's use of mental health services was determined by the proportion of participants who reported any mental health care use in the past six months, the proportion who were hospitalized for a psychiatric problem in the past six months, and the mean number of outpatient mental health visits in the past six months.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted with SAS version 6.12. We first describe the participants' mental health diagnoses at baseline by their source of income: SSI benefits, public income assistance, or no public income assistance. We then describe the participants' mental health status and service use by the three income sources at baseline and 24 months later and report the significant differences. To assess whether individuals with a preexisting mental health condition had a differential course, we stratified the sample by probable mental health diagnosis at baseline and assessed changes in mental health status between baseline and 24-month follow-up.

Results

A total of 253 respondents (82 percent of baseline participants and 65 percent of the total sample, adjusting for the ten individuals who were confirmed deceased and the one person who was misclassified) completed interviews at baseline, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months. A comparison of the 55 individuals who did not complete all four interviews with the 253 who did indicates that the two groups did not differ significantly in demographic characteristics, substance abuse, mental health status, or the length of time they had been receiving SSI benefits. Eleven of the 55 individuals who did not complete all four interviews died during the course of the study.

Of the 253 subjects in the final sample, 164 (65 percent) were male, and 134 (53 percent) were African American. Their mean±SD age was 44±9.4 years. Sixty-six (26 percent) were categorized as having no diagnosis, 69 (27 percent) had "stress," 70 (28 percent) had a probable depressive or anxiety disorder, and 48 (19 percent) had a probable psychotic or bipolar disorder.

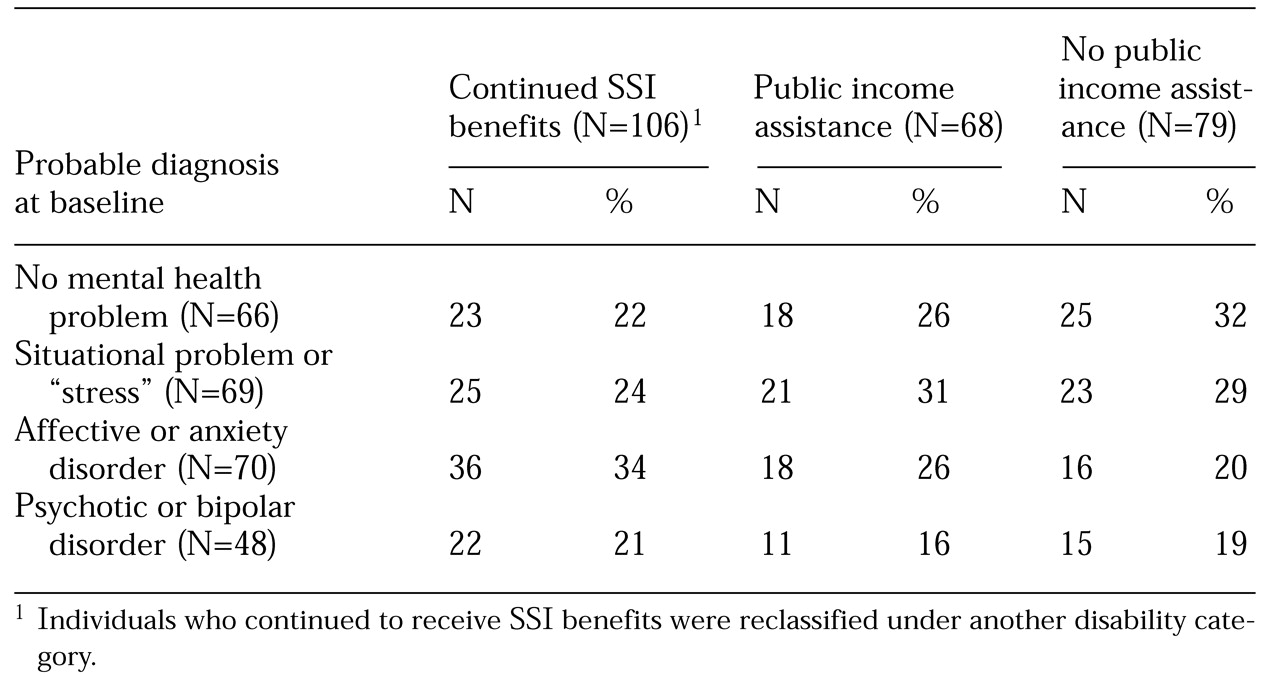

To determine whether a disproportionate number of individuals who had a probable mental disorder had lost SSI benefits, we analyzed the relationship between the participants' probable mental health diagnosis at baseline and their source of income at the 24-month follow-up (

Table 1). Chi square analyses showed no significant associations between probable diagnosis and source of income.

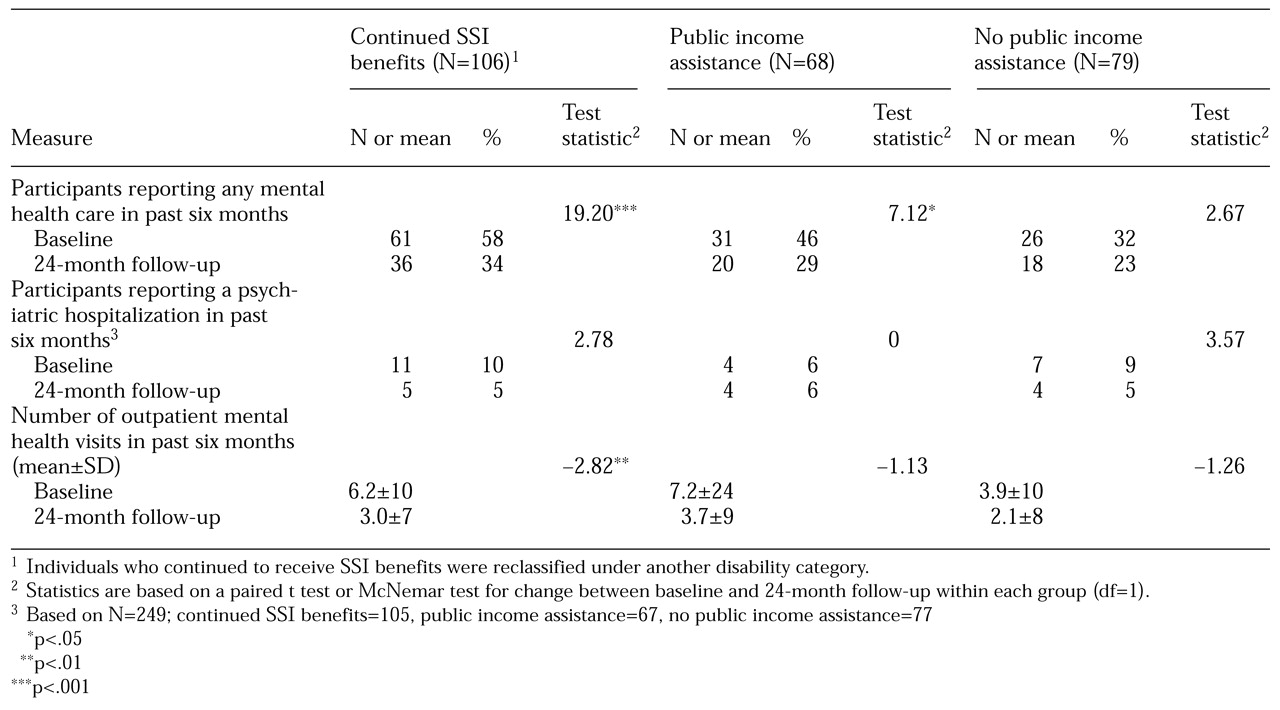

Table 2 contains information about the participants' mental health status by source of income at baseline and at 24-month follow-up. Emotional health status, current symptoms and problem severity, and disability either improved or were statistically unchanged; health status did not worsen for any of the three income groups. A repeat analysis to test the significance of changes in mental health status between the 12-month and 24-month follow-ups confirmed the results of the first analysis (data not shown).

The data shown in

Table 3 indicate that use of mental health services either declined or did not change between baseline and 24-month follow-up; the largest decline in use was among participants who continued to receive SSI benefits. A repeat analysis using data from the 12-month and 24-month follow-ups showed a similar pattern of minimally declining use, although the decline did not reach statistical significance (data not shown). Use of the emergency department for either a physical or a mental health problem decreased among participants who were receiving SSI benefits or who relied on other sources of income support and was unchanged among those who were receiving public income assistance (data not shown).

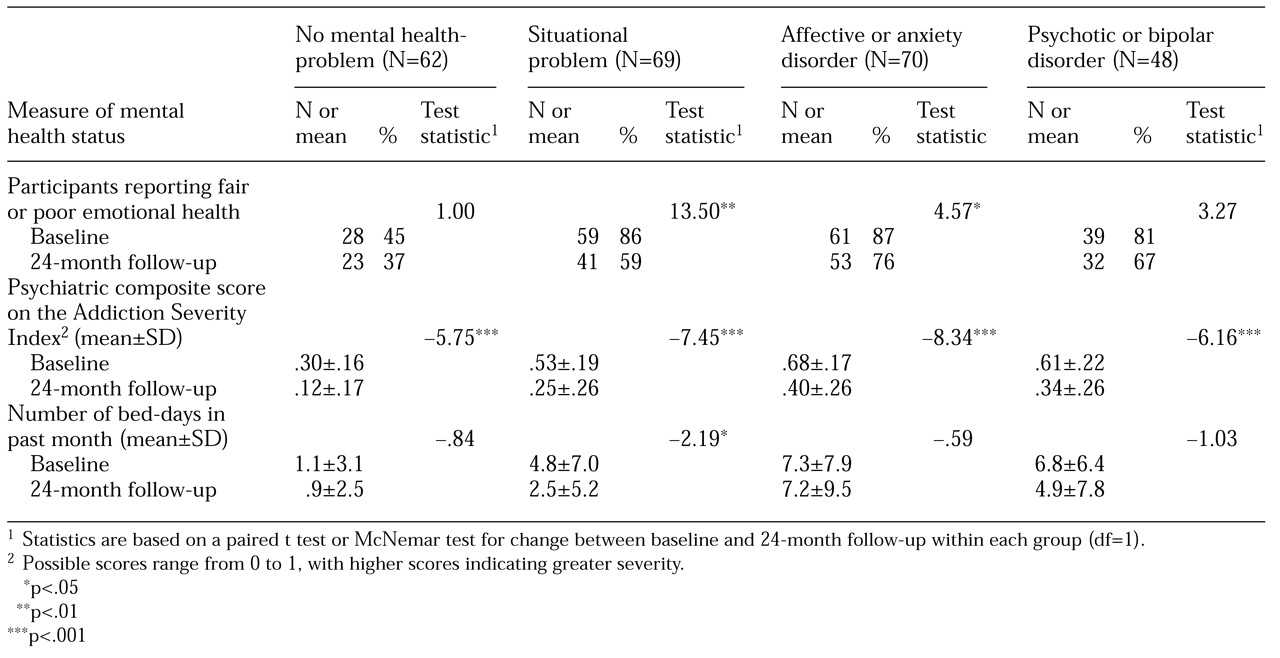

To clarify whether mental health status declined among individuals who had a more severe illness when the legislation took effect, we stratified the sample by probable mental health diagnosis at baseline and observed changes in mental health at the 24-month follow-up. The probable mental health diagnosis at baseline was used as a proxy for severity of illness. The data in

Table 4 show that the participants' mental health status improved or was statistically unchanged at the 24-month follow-up for all three groups.

Discussion

Despite widespread concerns that repeal of SSI benefits for a substance abuse disability would have a substantial and negative impact on the recipients' mental health (

11), our data suggest that mental health status did not worsen, even among individuals who were not reclassified under another disability and those who had a probable mental illness. On most of our measures, mental health either improved or did not change significantly from baseline, and it did not deteriorate on any measure.

For the first 10 months after the legislation took effect, the state of California extended Medi-Cal health insurance to individuals who lost SSI benefits, but by October 1997 those who were not reclassified had lost coverage. We expected that the loss of coverage would lead to a decrease in access to mental health care. However, our results show that although service use decreased slightly overall, the largest decrease was among individuals who continued to receive SSI payments and health insurance coverage.

There are a number of possible explanations for our findings. The Social Security Administration estimated that three-fourths of SSI beneficiaries who were scheduled to have their benefits terminated would be reclassified, primarily under a mental health disability (

12); however, fewer than half of the subjects in our sample had a probable major axis I diagnosis. Although it is unlikely that significant deterioration would have been seen among participants who had a minor or no mental illness, we found no deterioration in mental health status among those who had a probable disorder, which suggests that mental health did not decline, even among those who were most ill. It is also possible that participants who had a probable mental health disorder were less ill than expected.

Some individuals in our sample may have had a significant mental illness, but external factors helped prevent the deterioration in mental health that would have been expected. Our study took place during a period of significant economic growth and prosperity, which might have mitigated the adverse effects of the legislation. Individuals who lost income benefits may have relied on friends and family for support. Many individuals who lost health insurance may have obtained mental health care from the public mental health system, a possibility that is supported by our observation that neither outpatient visits nor inpatient hospitalizations declined significantly among individuals who lost SSI benefits, although the proportion who reported any mental health care use decreased slightly.

It is possible that the unexpected improvement in health status on some measures was due to the subjects' overreporting their mental health problems at baseline. In that case, a deterioration in mental health status would have been more difficult to observe. When our baseline data were being collected, many beneficiaries were attempting to prove that they had another disability so that they could continue receiving benefits. Although all the individuals whom we interviewed for the study were told that their participation would have no effect on their recertification, it is possible that they felt that by emphasizing their mental health problems, their chances for recertification would improve.

Alternatively, it is possible that the stress of losing benefits and going through a recertification process for which the outcome was uncertain created a temporary situation in which participants preceived—and reported—more mental health problems. In that case, the changes in mental health status between the 12-month and 24-month follow-ups in our study could be considered a better measure of the legislation's impact. However, most of the changes between those two follow-ups were not significant, and those that were significant were in the direction of improved mental health.

The decline in use of mental health services among the participants who continued to receive SSI benefits may be related to the reclassification process. At the time of the baseline interviews, many individuals who were subsequently reclassified were seeking to document a medical or psychiatric disability independent of their substance abuse, and they may have consulted a mental health care provider for assistance.

Our study has several limitations. Although we started with a random sample of beneficiaries, we had complete data for only two-thirds of our sample. It is possible that we did not interview the individuals who had the worst outcomes. However, a comparison of individuals who completed the follow-up interviews and those who did not showed no difference in mental health status at baseline. Eleven subjects (4 percent) died during the course of the study.

Our measures of mental health status were necessarily brief and were administered by interviewers who, although trained, were not clinicians. More comprehensive measures administered by clinicians may have captured more subtle changes in health status. It is striking, however, that many of the measures showed an improvement in health status—an unexpected result—which suggests that the measures were sensitive.

Conclusions

Clinicians, policy makers, and administrators can draw several conclusions from our study. First, contrary to expectations, the mental health of participants who lost SSI benefits did not worsen, even though their use of mental health services decreased slightly. These individuals continued to receive outpatient mental health care, and use of more expensive forms of care, such as emergency services or inpatient hospitalizations, did not increase.

Second, without outcome data from longitudinal studies, expectations about the impact of policy changes may be unfounded. At the time this study was initiated, there was widespread belief that the policy change would result in worsening mental health. The results of our study underscore the need for sound data to inform policy decisions. Third, local safety nets and the overall economy may mitigate the effects of federal policy changes that repeal or limit income assistance and health insurance benefits. To the extent that this is true, such legislation represents a cost shift from the federal government to states or local communities or to families and individuals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Rand's Drug Policy Research Center under grant 990-0633 from the Ford Foundation (Drs. Watkins and Burnam), the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment Target Cities/SSI Study grant U9-5TI00672 (Drs. Watkins, Podus, and Lombardi), and California Policy Seminar grant 014970 (Drs. Watkins, Podus, and Lombardi). The authors acknowledge the valuable contributions of Dan McCaffrey, Ph.D., M. Douglas Anglin, Ph.D., and Naz Dardashti.