Disability and quality of life are increasingly recognized as crucial factors in assessing mental health (

1). Although psychiatry has a long history of measuring functional impairment, these measurements have often been made with instruments designed specifically for use with psychiatric populations (

2), particularly persons with serious mental illness (

3,

4,

5). Limiting the concept of psychiatric disability to the more severe—and often less common—disorders may substantially underestimate the total impact of mental disorders on the health of the community. Furthermore, as funding for mental health services continues to be threatened (

6), measuring health outcomes in ways that are not comparable across various mental disorders or with other areas of health may mean that mental health is sidelined in the competition for resources.

An alternative to psychiatry-specific measures are the so-called generic measures of health status (

1,

7), which purportedly can be used across all areas of health care. Studies that have used generic measures have raised awareness in the general medical community of the importance of mental disorders as a cause of ill health (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15). But can generic measures inform comparisons of disability associated with various mental disorders? The few available studies suggest that the proportion of individuals who are disabled (

16) and the severity of disability (

17) vary according to the type of mental disorder and that after comorbidity and sociodemographic factors are controlled for, not all mental disorders are uniquely associated with disability (

8,

13,

14,

18). None of these studies investigated disability among persons with a current

DSM-IV diagnosis in a community sample. Furthermore, most studies covered a limited range of disorders and, in the case of some disorders, used small samples.

In this study we examined the Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short Form (SF-12) (

19) as a generic measure of disability and well-being across all the major

DSM-IV mental disorders. The SF-12 provides a mental health summary scale and thus was the most appropriate to our aim of investigating the comparative uses of generic measures in mental health. Specifically, we compared the prevalence and severity of disability associated with a large number of mental disorders in a cross-sectional community sample. We also examined the correlates and the importance of a diagnosis of a mental disorder in self-reported mental health disability and investigated which mental disorders were independently associated with disability after sociodemographic factors and comorbidity were controlled for.

Methods

Sample

The Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (

20) was a nationally representative household survey of mental disorders among adults. A stratified multistage and multiarea survey of private dwellings included individuals who were 18 years of age or older and who normally lived in private households. Persons in hospitals, nursing homes, jails, and other public facilities and those who lived in remote and sparsely settled parts of the country were excluded. A total of 13,624 dwellings were initially selected, and one adult in each dwelling was randomly selected as a potential respondent. A total of 10,641 people participated in the survey, for a response rate of 78 percent.

Participants were interviewed in their homes between May and August 1997 by experienced survey administrators from the Australian Bureau of Statistics who were trained to reliably administer the diagnostic interview. The interview was fully computerized. The interviewers asked the questions and entered the respondents' answers directly into the computer program. The participants received comprehensive written and spoken information about the purpose and nature of the interview. The study was conducted in compliance with the Federal Census Act of Australia.

The sample was weighted to match the age and sex distribution of the Australian population: the participants' mean age was 45 years, and 51 percent were women. Sixty-five percent of the participants were married, 63 percent were currently employed, and 48 percent had a college or university education. Most resided in a metropolitan area (73 percent) and were born in Australia (75 percent). Thus the sample was representative of the Australian adult population.

Diagnostic assessment

The survey incorporated the computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1, a fully structured diagnostic interview with good reliability and validity (

21). Participants were asked questions about symptoms pertaining to

DSM-IV diagnoses of affective, anxiety, or substance use disorders during the previous 12 months. These symptom responses are assessed against the diagnostic criteria to generate diagnoses (

21). Drug use disorders included abuse of and dependence on cannabis, sedatives, amphetamines, or opioids. However, the rates of use for individual drugs were too few for their numbers to be presented separately. Drug and alcohol abuse entail abuse without dependence.

We were concerned only with current diagnoses—those for which the participants had experienced symptoms in the previous four weeks—because disability was assessed over a four-week period.

DSM-IV exclusion rules were not applied. Screening instruments were used to identify likely cases of the nine

ICD-10 personality disorders (

22), psychosis (

23), and neurasthenia (

24), which is included under

DSM-IV undifferentiated somatoform disorders (

25). Physical disorders were assessed with a self-report yes-or-no checklist for 12 common chronic conditions: asthma, chronic bronchitis, anemia, high blood pressure, heart problems, arthritis, kidney disease, diabetes, cancer, stomach or duodenal ulcer, chronic gallbladder or liver problems, and hernia or rupture (

26).

Measures of disability

Participants completed three measures that assessed disability during the previous month: the SF-12, the Brief Disability Questionnaire (BDQ) (

10), and the number of disability days. The 12 items on the SF-12 are summarized in two weighted summary scales—mental health and physical health; lower scores indicate more severe disability. The items related to mental health cover limitations to usual activities and emotional state. We report only the results of the mental health summary scale, which has adequate test-retest reliability (r=.76) and sensitivity to recovery from depression (

19). The SF-12's parent measure, the SF-36, has been shown to have good psychometric properties and has been used successfully in outpatient psychiatric settings (

6). The BDQ's five-item role functioning subscale (

27) was used in this study for comparisons with mental health disability. The number of disability days is a summary measure of the total number of days in the previous four weeks in which activities could not be performed or had to be scaled down because of ill health (

8).

Analysis

All proportions and mean scores represent weighted values to account for the probability of an individual household member's being selected and to comply with the age and sex distribution of the Australian adult population. Although familiar statistical procedures—linear regression and logistic regression—were used to analyze the data, the complex sampling strategy required the use of specialized software to perform the statistical analysis and to estimate standard errors. This software takes into account the variability within and across the geographical sampling units from which the survey respondents were randomly selected. Without such software, variance in statistical estimates can be underestimated, which could result in statistically significant findings that would not otherwise have been significant. Variances in these estimates—proportions, odds ratios, and nonstandardized regression coefficients—were thus estimated with use of the SUDAAN software package for survey analysis, version 7.5.3 (

28).

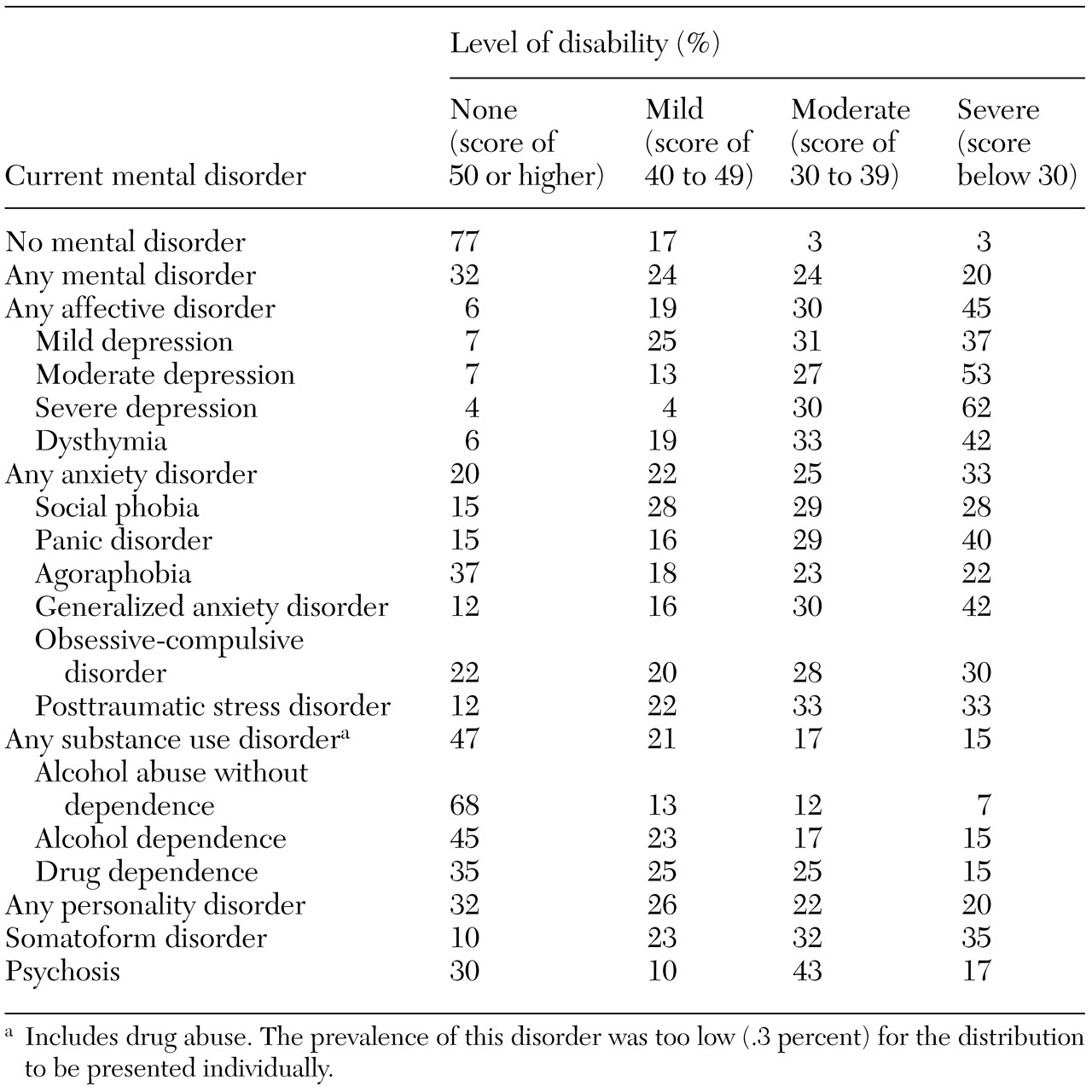

The prevalence of disability was obtained by categorizing individual scores on the SF-12 mental health summary scale into four levels of disability: no disability, represented by a score of 50 or higher; mild disability, 40 to 49; moderate disability, 30 to 39; and severe disability, a score below 30. This classification was considered useful because the SF-12 score is not readily interpretable.

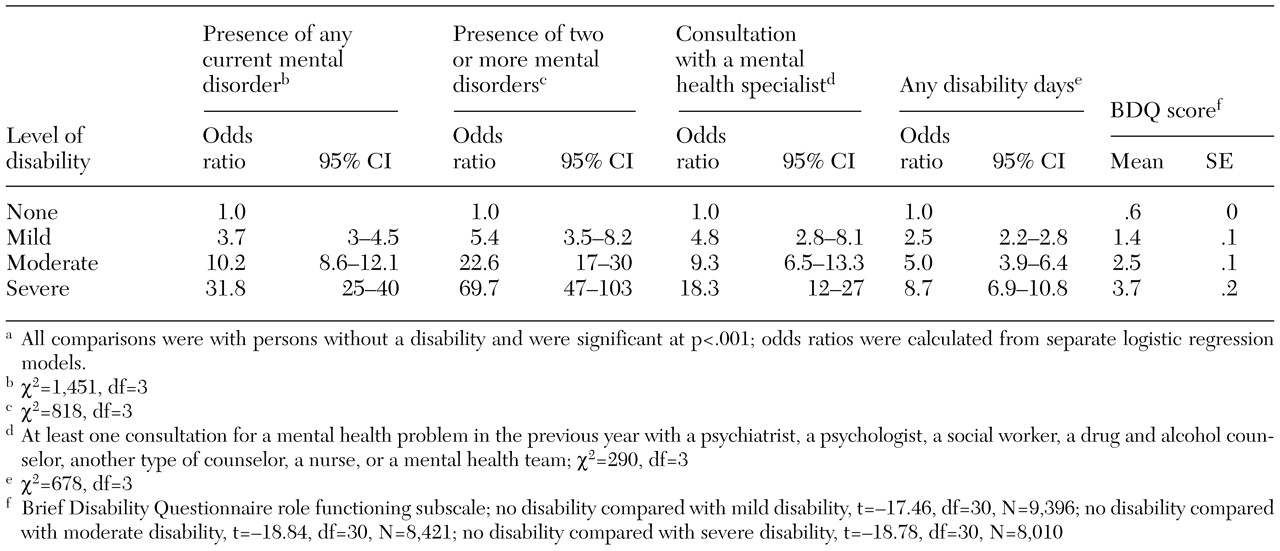

These four levels of disability were adapted by collapsing a nine-level categorization used by Ware and colleagues (

29) to help interpret the mental health summary scale—9 to 29, then seven five-level increments (30 to 34, 35 to 39, and so forth), and then 65 to 74. The validity of the four levels of disability was investigated by comparing them with five disability-related variables: presence of any current mental disorder as opposed to none, presence of two or more mental disorders as opposed to one or none, consultation with a mental health specialist—a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, a counselor, a nurse, or a mental health team—as opposed to no consultation, significant difference in mean BDQ score as opposed to no significant difference, and any disability days as opposed to no disability days.

We calculated unadjusted odds ratios by using logistic regression for the dichotomous variables to assess the simple relationship between disability levels and the related variables; significance was assessed with the Wald chi square statistic. The significance of differences in BDQ scores was determined with planned contrasts. These analyses were used to determine whether an increasing level of disability was mirrored by increases in the five disability-related variables. Significance was controlled at .05 by dividing by the number of disability variable comparisons (.05 divided by 5=.01).

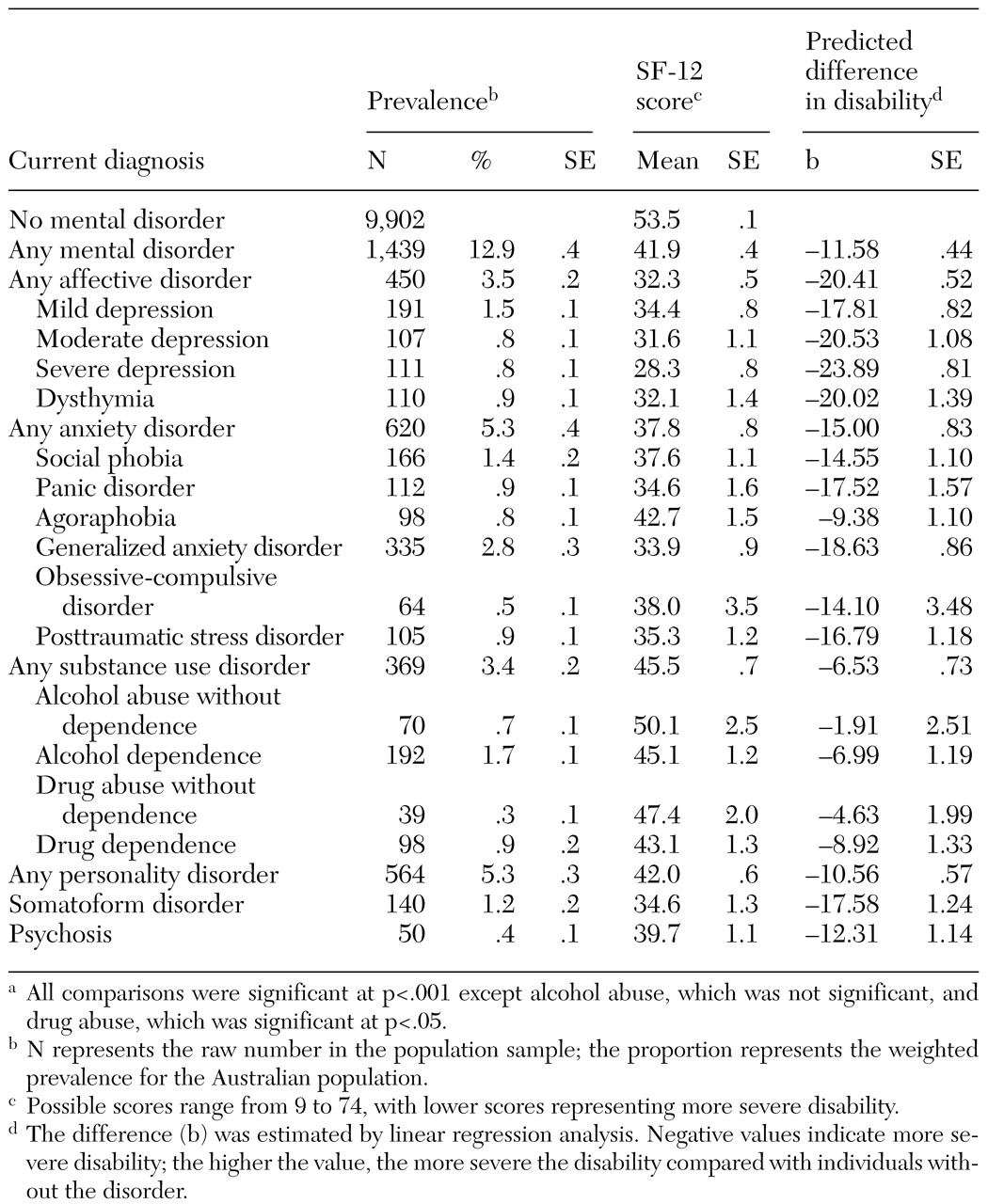

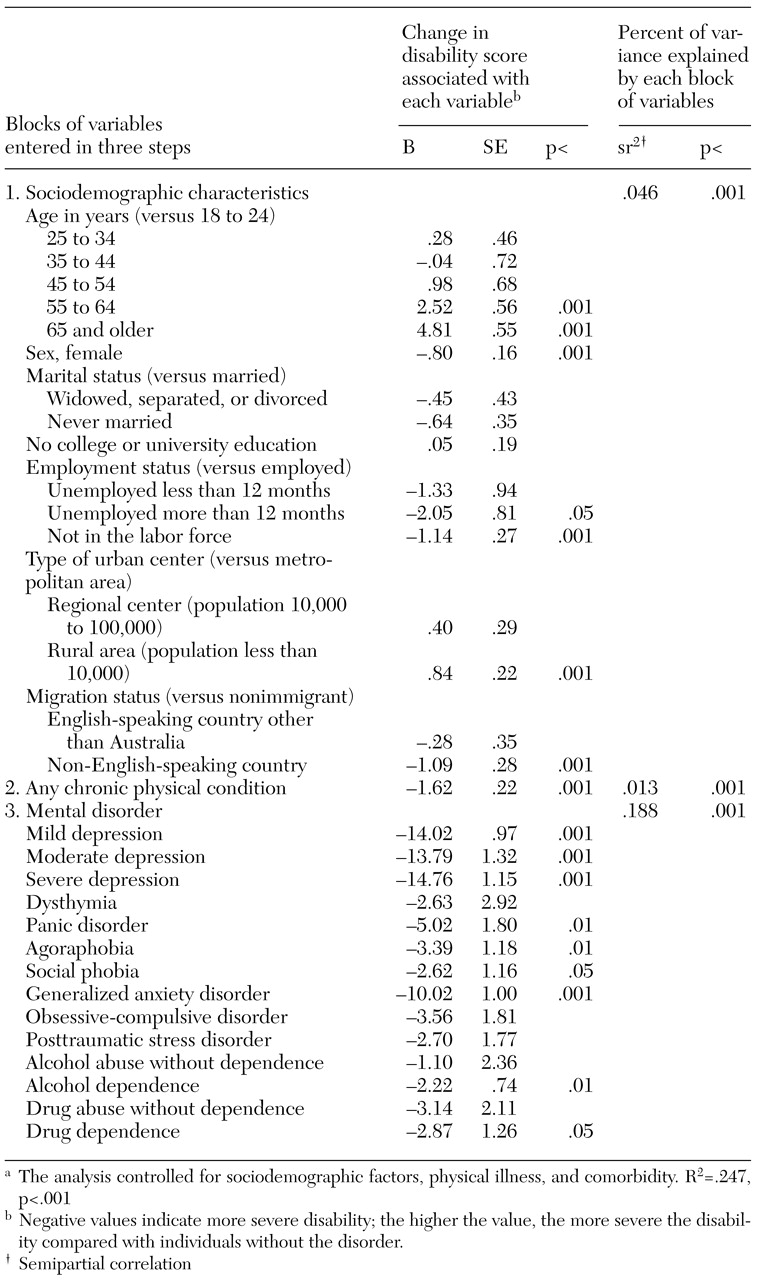

Disability related to each disorder was first examined through mean scores and bivariate regression coefficients from bivariate linear regressions. These coefficients predict differences in SF-12 scores between persons who have a particular disorder and those who do not have that disorder. We then conducted a hierarchical linear regression to examine the correlates of disability in the entire community sample and the strength of the association between disability and diagnosis when other factors were controlled for. This analysis also provides the predicted difference in SF-12 scores for each diagnosis but controls for the influence of sociodemographic variables and co-occurring mental and chronic physical conditions.

The variables were entered in three steps; the third step determined the importance of the DSM-IV diagnosis in predicting disability when the previously entered variables were controlled for. The statistical comparisons were with persons who did not have a particular disorder; for the multivariate hierarchical regression, significance was set at .05 or less.

Discussion

The generic SF-12 measure demonstrated variation in the proportions of people who reported mild, moderate, or severe disability. All mental disorders except alcohol abuse were significantly associated with some disability, although not all associations were significant after comorbid conditions—both physical and mental—were taken into account. We have extended the work of another population-based study (

30) that showed a relationship between disability and depression and generalized anxiety disorder that was independent of comorbidity and sociodemographic factors by showing that this relationship exists for other anxiety disorders—panic disorder, agoraphobia, and social phobia—and substance dependence. In general, a diagnosis of a mental disorder was the strongest predictor of disability in our study after sociodemographic factors and physical illness were taken into account.

The finding from other studies of a strong independent association between depression and disability (

13,

14,

18,

30,

31) was replicated in our study. An item of the SF-12 that directly assesses depressive symptoms— "Have you felt down-hearted and blue?"—may have artificially inflated this association. A study that used the SF-12 in a primary care setting (

31) showed a highly significant association between probable depression and disability when the summary scale was used. However, a smaller—but also highly significant—relationship was found for the social and role functioning items of the SF-12, excluding the depression item. Thus use of the depression item of the SF-12 seems to overstate an existing relationship between depression and disability; it does not artificially create a relationship.

The association between anxiety disorders and disability in our study and in others (

11,

15,

30,

32) was genuine and was not solely due to comorbidity, given that most anxiety disorders were uniquely associated with disability. Unlike Olfson and associates (

14), whose study was limited by a small sample, we found independent relationships between disability and generalized anxiety disorder—as did Kessler and associates (

30)—and between disability and panic disorder. Posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder were not found to be independently related to disability in either our study or the study by Olfson and associates (

14). Evidence from a population-based study (

9) also suggests that after comorbidity is taken into account, obsessive-compulsive disorder is only moderately disabling compared with depression and panic disorder.

In our study, alcohol dependence without abuse was independently associated with disability. These findings replicate those of a study that used the SF-36 in a primary care setting (

33). Similarly, drug dependence without abuse was independently associated with disability. These results clarify earlier reports from primary care settings (

13,

14) by showing that dependence—but not abuse—is the disabling component of both alcohol and drug use disorders.

Our data for psychosis, personality disorders, and somatoform disorder are useful, because few community surveys have included these disorders. The association of somatoform disorder with disability was comparable to that of depression. Personality disorders and psychosis were associated with milder—but nonetheless significant—disability. It is possible that general measures of functioning are not sensitive to the large deficits observed among persons who have serious mental illnesses (

34). Alternatively, the less severe disability scores of participants with psychosis could reflect the fact that these participants constituted a small and atypical subsample. This explanation is supported by the results of a recent epidemiological survey (

17) in which schizophrenia was found to be the most disabling disorder. Furthermore, improvements in scores on SF-36 subscales have been observed among persons with psychosis, bipolar disorder, and depressive disorders, reflecting the change observed on psychiatry-specific measures (

35).

One of the limitations of this study was that disability and the symptoms on which diagnosis was based were entirely self-reported, which could have contributed to the strong overlap between the two. However, if that were so, there would be no reason to suspect that this effect would operate differentially by disorder—it would be similar across all the disorders. The data in

Table 1 show that this was not the case. Furthermore, in a community survey by Bassett and associates (

16), in which both diagnosis and disability were assessed by psychiatrists, persons with affective disorders and anxiety disorders reported worse functioning than those with substance use disorders. These findings are similar to those of our study.

More generally, the validity of self-reported health status among persons with chronic mental illness has been both questioned (

34) and supported (

36). Self-report is often the only option for epidemiological surveys (

7) and in busy clinical settings because of time and resource constraints. The inclusion of the consumer's perspective (

1) is an equally important justification for the continued use of self-report measures, particularly given that these measures appear to provide valid information that is different from that provided through observer-rated measures (

36). Future epidemiological studies could supplement self-report measures with lay interviewer-rated measures, as was done by Leon and associates (

37). The lack of a standard measure of disability encourages a broad range of perspectives (

16); self-reported generic measures represent one such perspective (

1).

Our finding that the prevalence and severity of disability vary by diagnosis suggests that the SF-12 is sensitive to differences in disability across types of mental disorder. However, our study was cross-sectional only. Future research should focus on the sensitivity of generic measures such as the SF-12 to changes in mental health status, because demonstration of the effectiveness of treatment is crucial to maintaining funding for mental health services (

6).

The results of this study indicate that focusing only on disability that is associated with serious mental illness might result in substantially underestimating the impact of mental disorders on the health of the community. If the alleviation of disability is considered a goal of treatment (

1), then depression and anxiety disorders in particular should be a primary focus of policy initiatives: both disorders are disabling, but both can be treated cost-effectively (

38,

39). Finally, users of the SF-12 mental health summary scale should be particularly concerned about individuals with scores below 30, because these persons are severely disabled and should not go untreated.