The staff of correctional health care facilities focus primarily on the health and behavioral health care of inmates while they are still inside the jail. The challenge for both correctional and community providers is to maintain the treatment connection as persons with chronic illness move from one setting to another. Although jails have historically defined their responsibilities in terms of health and security issues that occur within their walls, release planning extends beyond those boundaries (

1). States and courts are beginning to alter the boundaries between the jail and the community (

2), yet little is known about whether and to what extent the staff of correctional health care facilities consider release planning to be important, whether they are taking the necessary steps to connect inmates with treatment when they are discharged, and whether their effort varies according to the inmate's chronic condition.

Most of the research on community reintegration has focused on the relationship between recidivism and case management provided to inmates who have serious mental illness before and after release (

3,

4,

5,

6). One study, which examined seven jails located throughout the country, found little evidence of release planning, although the jail staff recognized that coordinating care for detainees with mental illness was necessary for continuity of care (

7). In the study reported here we evaluated the release planning performance of jails in one state—New Jersey. This type of study is important because it speaks to the broader issue of whether release planning is idiosyncratic to a particular geographic location.

We evaluated the release planning process for three types of chronic illness—mental illness, heart disease, and HIV infection or AIDS—to determine whether release planning for persons with mental illness differs from that for persons who have other types of chronic illnesses. All these conditions have two common characteristics—they are chronic, and they require continuous medical treatment.

Methods

Of the 21 county jails in New Jersey, 17 (81 percent) participated in this study. The other four jails refused to participate because of ongoing legal problems, lack of interest in research, or a belief that the jail's inmates did not have mental health problems. Interviews were conducted with correctional health care staff and ranged in duration from four to eight hours. The survey instrument included closed- and open-ended questions and is available on request. The interviewees (one respondent per jail) were primarily health services administrators. The interviews were conducted in August, September, and October of 2000. At a briefing held in August 2001, the study participants provided feedback on the validity of the findings.

Because we were interested in the treatment of mental illness as one aspect of a continuum of chronic health problems, the respondents were asked about efforts to link inmates who had heart disease, HIV infection or AIDS, or serious mental illness with treatment after their release. The interview questions that were designed to assess the importance of release planning were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, not important, to 5, extremely important.

Results

When asked to rate the importance of release planning for persons with serious mental illness, 71 percent of the respondents (12 jails) reported that it is very or extremely important. A comparable level of importance was reported for heart disease (ten jails, or 59 percent) and HIV infection or AIDS (12 jails, or 71 percent). Yet virtually all the jails also reported that they provide "no real release planning."

About three-quarters of the jails reported providing some type of release planning for inmates with serious mental illness (13 jails, or 76 percent). The number of jails reporting release planning varied from four (24 percent) for heart disease to 14 (82 percent) for HIV infection or AIDS. Of the facilities that reported active release planning, the percentage of inmates with release plans varied by chronic illness. On average, 9 percent of inmates with heart disease, 52 percent with HIV infection or AIDS, and 41 percent with serious mental illness were released with release plans.

These averages conceal the large variation in effort among facilities. Ten facilities reported that they provide aftercare plans for fewer than 10 percent of inmates with mental illness on release, whereas three facilities reported that they provide release plans for 75 percent to 100 percent of their inmates with a mental illness. Release planning for particular chronic problems was most common and complete in facilities that had special treatment programs, such as a mental health unit or an HIV and AIDS partnership. In such cases, the release planning was particular to the program, not to the entire facility.

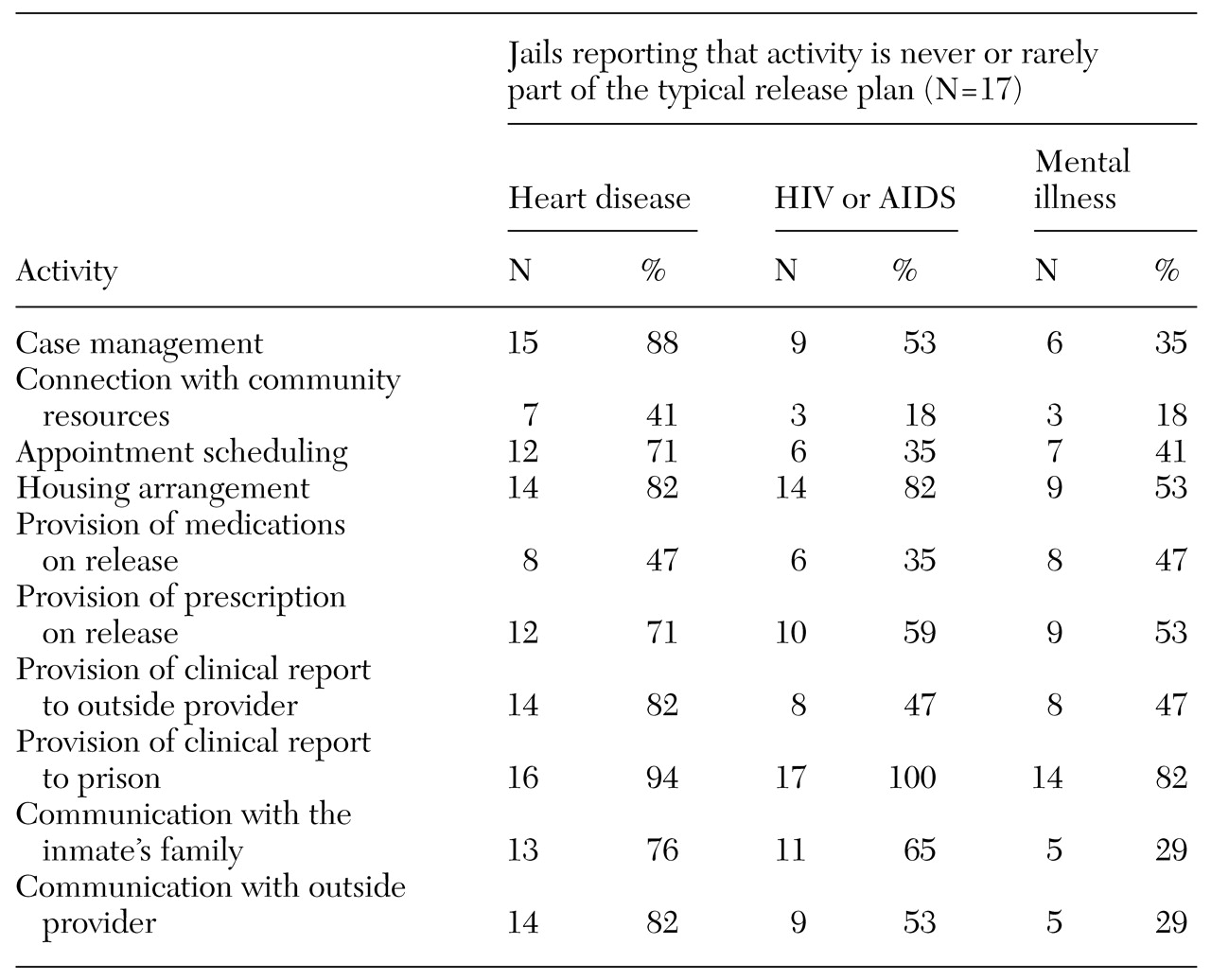

Table 1 shows the frequency with which common types of planning activities are rarely or never included in the "typical" release plan. No particular activity is always or often included in the release plan for inmates with any of the chronic conditions, with the notable exception of provision of a clinical summary and treatment plan to the prison for inmates who are transferred there. Connection to community resources—which typically involves giving inmates the telephone number of a provider, a treatment center, or a clinic—is sometimes part of release planning.

About half of the jails reported that they never or rarely provide inmates who have serious mental illness with medications or a prescription for medications when they are released. Only two facilities reported that they routinely release inmates who have serious mental illness with psychotropic medications, whereas nine facilities reported that they have policies that actively discourage such practices. Yet we found that around 20 percent of inmates in New Jersey jails receive psychotropic medications while they are incarcerated. Almost half of the jails reported that they never or rarely provide inmates who have heart disease with medications on release. Jails are more likely to provide inmates who have HIV infection or AIDS with medications when they are released. Only 35 percent of the jails reported that they never or rarely release inmates who have HIV infection or AIDS with medications.

When asked to rate the quality of their release planning for inmates, a majority of respondents rated their performance as fair or poor. The lowest rating was given to release planning for inmates who have heart disease, with 14 jails (82 percent) assigning a rating of poor or fair, compared with 12 jails (71 percent) assigning such a rating for inmates with HIV infection or AIDS and 11 jails (68 percent) assigning such a rating for inmates with serious mental illness.

Discussion and conclusions

This evaluation showed that the lack of release planning is not unique to mental illness. Although jails appear to be reluctant to assume primary responsibility for release planning, there is evidence that they are willing to build community connections that facilitate such planning. Eight jails reported having partnerships with HIV and AIDS clinics that involved these clinics providing on-site screening, treatment, case management, release planning, and follow-up aftercare to all inmates who were identified as being HIV positive. Connections like these were not found between the community mental health system and the jail.

Connecting inmates who have mental illness to community mental health services is critically important, according to the American Association of Community Psychiatrists (

8) and a task force of the American Psychiatric Association (

9). A sizable percentage of New Jersey inmates are identified as having mental health problems and are treated with psychotropic medications while in jail. However, most of these inmates are released without effective linkages to medications or psychiatric services, both of which are essential for maintaining their mental health.

Continuity of care is vitally important to the health of inmates and to the general public. It does not make clinical or economic sense to provide treatment to inmates who have chronic conditions while they are incarcerated and then not arrange for aftercare in the community. Finding a stable and reliable solution to the release planning problem begins with dedicated funding to support release planning staff, provide transitional care, and create liaison positions to build community linkages. Bridging gaps between the jail and community, state, and local funding streams is necessary if continuity is to be realized.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grant MH-43450 from the University of Medicine and Dentistry New Jersey-Rutgers School of Public Health and the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank William Fisher, Ph.D., Jeffrey Draine, Ph.D., and Phyllis Solomon, Ph.D.