Interest in measuring level of functioning has increased dramatically in recent years (

1,

2). With the introduction of managed care, consumers and advocates have expressed concern that service limitations may lead to poorer client functioning (

3,

4). New technologies, such as atypical antipsychotic medications (

5), and best practices, such as assertive community treatment (

6), raise the possibility that persons who have severe psychiatric conditions might be able to increase their capabilities.

Weissman (

1) defines functioning as "performance in social roles" such as interacting with others, forming relationships, and handling day-to-day tasks, such as managing money. People who have severe mental illnesses may need additional skills, such as those necessary to manage mood swings, take medications, and work with treatment providers. Level-of-functioning instruments measure a person's ability to perform these daily tasks.

Uses for level-of-functioning measures

Hodges and Wotring (

7) note that "functioning has come to be viewed as a critical outcome indicator." For example, the state of Iowa used a level-of-functioning instrument—the Multnomah Community Ability Scale—as a performance measure when its Medicaid behavioral health program for clients with severe mental illness was contracted to a managed care company (

8,

9). Measures of function have also been used to summarize consumers' needs in order to match clients with appropriate programs (

10,

11). Similarly, it has been suggested that such measures be considered in decisions about placement or level of care for consumers (

12). Measures of function are also used in rate setting for capitated payment systems (

13,

14) and in determining level of disability (

15).

Several instruments have been designed for persons who have severe and persistent mental illness (

1,

2,

16,

17,

18). The various types of measures of functioning include tools intended for the consumer, the confidant, the clinician, the interviewer, or the observer (

19). Most instruments are designed to be completed by clinicians, such as case managers (

2,

16,

17,

18). Williams (

2) pointed out that few instruments have a consumer self-report version.

Importance of self-report measures

Consumer self-report information on level of functioning could have an important role in evaluation and treatment. Campbell (

20) advocates "interactive, collaborative practice … that will allow divergent views to be shared." Lang and colleagues (

21) found that "clinicians and clients may measure improvement differently." Studies using the Wisconsin Quality of Life Index have indicated that consumers and providers of behavioral health care have different points of view about life satisfaction (

22,

23,

24). Eisen and associates (

25) found that engagement in treatment increased among inpatients who completed a self-rated symptom scale and discussed the results with staff.

Boothroyd and colleagues (

26) point to the considerable interest in assessing outcomes for populations such as persons enrolled in managed care plans. However, it may be difficult—or even impossible—for clinicians, interviewers, or observers to evaluate functioning among individuals who may or may not be receiving services at any given time (

20). Consequently, self-report instruments that can be administered by mail, through telephone interactive voice response, or over the Internet would be attractive.

Few consumer self-report measures of functioning have been designed for persons with severe mental illnesses. Instruments such as the Social Adjustment Scale Self-Report (

27) and the Social Adaptation Self-Evaluation (

28) have, in general, been used by persons with major depressive disorder who are participating in clinical trials. The Social Functioning Scale is a lengthy instrument used chiefly in the United Kingdom (

29). Little use has been made of the 57-item Community Living Skills Scale (

30). Wallace and colleagues (

15) recently developed a 63-item self-report version of the Independent Living Skills Survey (

31), the informant version of which contains 103 questions. Although these instruments can provide important details about the "molecular" aspects of behavior (

32), such lengthy scales may be difficult to use in everyday practice.

The Multnomah Community Ability Scale as our model

To meet the need for a self-report measure of functioning designed for persons with severe mental illness, we developed a consumer self-report version of the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS), a 17-item instrument designed to be completed by case managers working with adult clients who have severe and persistent mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, and who live in the community (

33,

34). The MCAS was produced jointly by researchers and community mental health program staff using a Q-sort process (

35) to select candidate items for the instrument. The complete instrument (

33), which fits on a single sheet of paper, is available from the authors, as are training videos and user manuals.

The instrument contains questions such as "How successfully does the client manage his/her money and control expenditures?" There are five possible responses, ranging from 1, "almost never manages money successfully," through 3, "sometimes manages money successfully," to 5, "almost always manages money successfully." The MCAS addresses four areas: interference with functioning, adjustment to living in the community, social competence, and behavioral problems. Users are asked to consider the preceding three months as the period of interest and to use all available information, including discussions with the client and informants as well as medical records.

The interrater reliability of the MCAS was recently replicated in Australia (

36). The instrument has also demonstrated considerable predictive validity, with high inverse correlations between ratings and subsequent psychiatric hospitalization (

33,

37). Two recent studies showed that the clinician version of the MCAS is sensitive to change (

5,

6).

In her review of measures of functioning, Williams (

2) recommends the MCAS for use with persons who have severe mental illness. The instrument has been used to examine the residential stability of clients who have severe mental illness (

38), differences between persons with bipolar disorder and those with schizophrenia (

39), the impact of neurocognitive deficits on persons with schizophrenia (

40), and the utility of medication algorithms (

5). Psychometric properties of the MCAS have been examined in research settings (

41) and field settings (

42).

Methods

Instrument development

We modified the MCAS for use by consumers in a self-report format (MCAS-SR). The instrument's introductory text was changed to address the consumer and to emphasize the time frame of the preceding three months. The stems for each item in the clinician version were changed into questions addressed to the consumer. Examples were provided for several items. For instance, one item asks, "How well do you manage day-to-day tasks on your own? (For example, tasks such as getting dressed, obtaining regular food, dressing appropriately, or housekeeping)." As in the clinician version, the possible responses to each item ranged from 1 to 5.

Early editions of the consumer version of the MCAS were tested among persons with chronic mental illness who were living in a group home. Items that consumers thought were inappropriate, unclear, or difficult to read were rewritten. Four peer counselors who were employed by a community mental health agency were also asked to examine the draft, and the instrument was again rewritten. The next version was distributed to 22 attendees of a community mental health drop-in center, of whom 20 returned the instrument. Comments were solicited from these consumers, and they were asked about any difficulties they had in completing the instrument. Yet another revision produced the current one-page, double-sided version of the MCAS-SR, which was used in subsequent investigations. Possible scores on the MCAS-SR range from 17 to 85, with higher scores indicating better functioning. The full text of the instrument is available from the authors.

Procedures

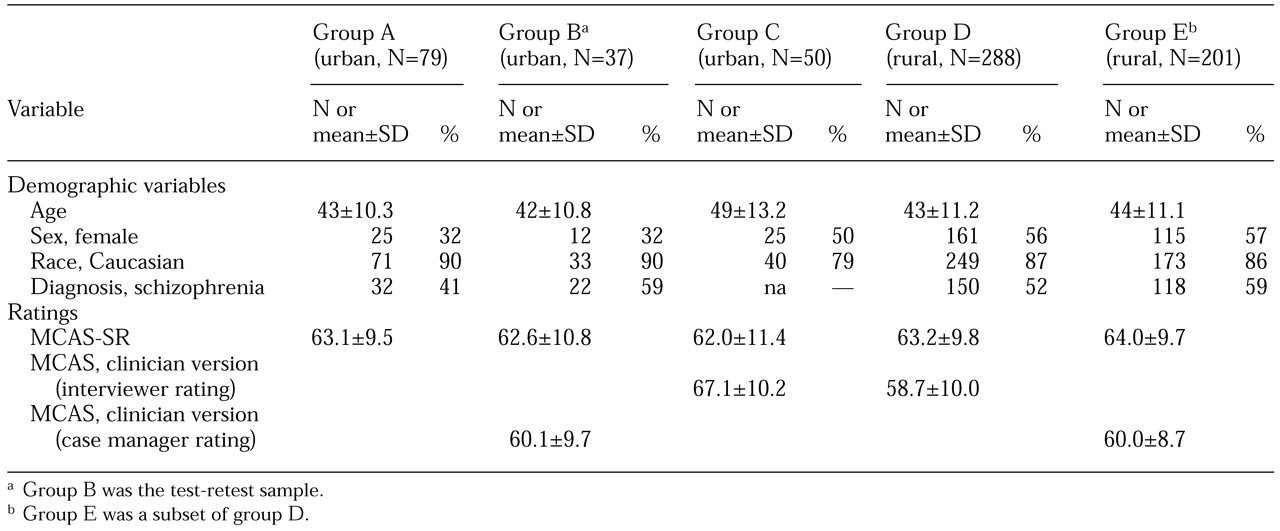

The instrument was completed by an additional 79 consumers recruited through flyers distributed by staff members of seven different programs—four case management programs, two drop-in centers, and one peer counseling program—in urban areas (group A in

Table 1). Clients gave written informed consent and then completed the instrument in groups with the assistance of research personnel as needed. They were asked to provide demographic information, to complete the MCAS-SR, and to answer questions about any difficulties they encountered in completing the instrument.

Standard methods were used to examine reliability and construct validity (

35,

43). Test-retest reliability was measured with an additional 40 consumers recruited from two case management programs and two drop-in centers (group B in Tables 1 and 2). Participants completed the MCAS-SR at their initial meeting with the researchers and again two weeks later. Intraclass correlation coefficients were computed to measure test-retest reliability (

44). In addition, scores from the clinician version of the MCAS—completed closest in time to the date of the client's self-report—were obtained from community mental health program records.

A random sample of 54 Medicaid clients with severe and persistent mental illness was drawn from county mental health databases for a consumer satisfaction survey (group C in the tables). Clients completed the MCAS-SR, and interviewers completed the clinician version of the instrument.

The MCAS-SR was also included in the instrument package used by the Oregon site of an ongoing nationwide study of Medicaid managed behavioral health care and vulnerable populations, supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medicaid clients with severe and persistent mental illness were recruited from rural community mental health programs. The 304 study participants (group D in the tables) were interviewed with a battery of instruments, including the Brief Symptom Inventory (

45) and the Short Form-12 (SF-12) health status measure (

46). The global severity index from the Brief Symptom Inventory and the SF-12 mental component summary (MCS) scores were correlated with the MCAS-SR total scores. Scores on the clinician version of the MCAS completed by the rural consumers' case managers at the times closest to the dates of the research interviews were also retrieved and correlated with the MCAS-SR total scores (group E in the tables).

We computed Cronbach's alpha to examine internal consistency (

47). Because the instruments were made up of Likert scales, nonparametric measures, such as Spearman's rho, were used in the data analysis (

48).

The study was conducted between 1997 and 1999 and was approved by the institutional review board of the Oregon Health Sciences University.

Results

Acceptability

The peer counselors said they considered the MCAS-SR to be acceptable from the consumer's perspective and possibly useful in determining clients' needs for services. They also suggested that the instrument might help consumers track their progress. They considered the language used in the instrument to be understandable. Overall, the peer counselors thought that the MCAS-SR addresses areas that are relevant for consumers but that it should solicit more information about housing and employment.

Of 22 attendees at the urban drop-in center who were given the MCAS-SR, 20 (91 percent) completed the instrument. These persons were generally believed by staff of the community mental health program to have severe and persistent mental illness often complicated by substance abuse. However, by design, the drop-in center served people who declined to participate in formal mental health services and thus lacked diagnoses and clinical records. These 20 participants had a mean±SD MCAS-SR total score of 59.2±8.2. They said that they did not find the instrument to be difficult to complete.

Demographic information for the 79 urban clients who completed the MCAS-SR (group A) is included in

Table 1. About ten clients came from each of the urban community mental health programs—four case management services, two drop-in centers, and a peer counseling program. The scores varied considerably (Kruskal-Wallis test statistic=29.8, p<.001). For example, participants from the drop-in center had the lowest scores (poorest functioning), with a mean± SD total score of 59.9±8.5, whereas the peer counselors had the highest mean total score (70.1±4.9).

Most of the clients in group A were able to complete the form without assistance within ten minutes. However, 16 clients (20 percent) needed help from research staff to read and understand the questions. Reasons for needing assistance included poor vision, illiteracy, and confusion. Clients who needed assistance had notably lower scores than those who did not need assistance (Mann-Whitney χ2=11.3, df=1, p<.001).

Reliability

The test-retest reliability study included 40 participants. However, three of them were unable to attend the second session; one was admitted to the state mental hospital, one had a respiratory illness, and one had "personal business" that precluded attendance. Complete data were available for 37 participants (group B in the tables). Nineteen (51 percent) of them were clients of case management programs, and the others were recruited at the drop-in center.

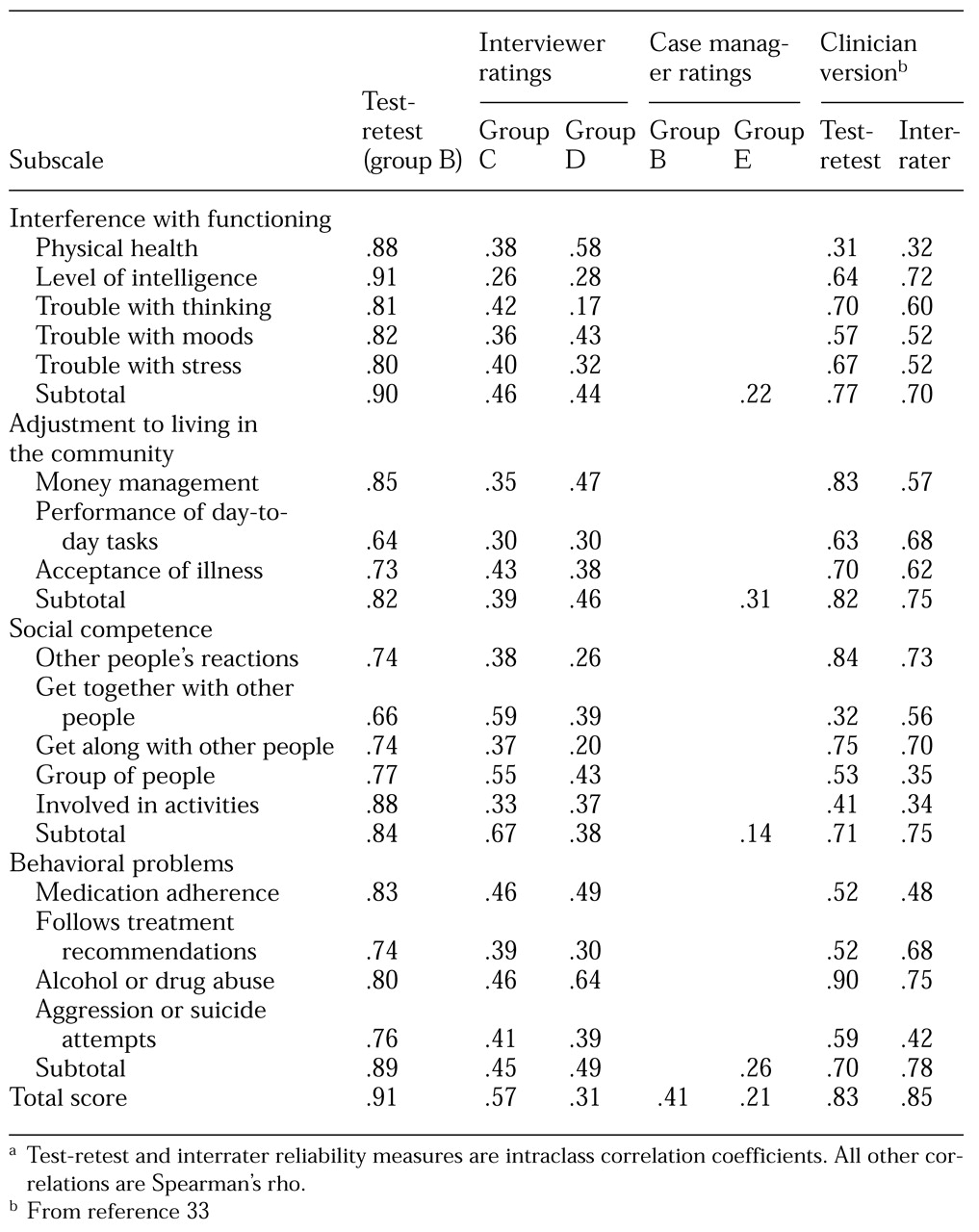

Table 2 includes the test-retest reliabilities for each item of the MCAS-SR. These intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from .64 to .91. The test-retest correlations were significant at the .001 level (df=35) for all 17 items. For the subtotals of each subsection, the test-retest reliabilities were .90, .82, .84, and .89, respectively; for the total score, the test-retest reliability was .91. These intraclass correlation coefficients were all statistically significant at p values below .001 (df=35). All the Cronbach's alpha coefficients exceeded .82.

Consumer and interviewer ratings

Self-ratings and ratings by research interviewers were available for 50 urban and 288 rural Medicaid clients with severe mental illness (groups C and D, respectively). The total score correlations were .57 for the urban clients (p<.01, df=48) and .31 for the rural clients (p<.001, df=286). No items had notably low correlations between self-report and research interviewer scores.

Consumer and case manager ratings

Clinician versions of the MCAS were completed for 37 of the urban participants in the test-retest sample (group B) and for 201 rural clients (group E). On average, case managers rated participants within about two months of the consumer's self-report. For the urban consumers the correlation between the self-report and the case manager's rating was .41 for the total score (p<.05, df=35). For the rural consumers the correlation was .21 (p<.002, df=199). Consumer and case manager ratings were also available for the four subscales in the rural sample (group E). None of the subscales had markedly low correlation.

Additional analyses were undertaken to examine the low correlation between self-report and clinician ratings for the rural sample, which could have been due to "range restriction" (

35). Although the total score on both the clinician and the self-report versions of the MCAS can range from 17 to 85, about three-quarters of the clients in the rural sample were rated in the 50s or 60s by their case managers. Therefore, the data set for the rural clients was reduced to yield a less homogeneous subsample. Study participants with scores below 50 or above 70 were included in the analysis, but only 30 percent of participants who had case manager ratings from 50 to 70 were included in order to yield a reduced data set of 95 observations with a mean±SD clinician total score of 59.8±11.1. The distribution was rectangular, ranging from 38 to 78. The mean total self-report score for this subsample was 64.3± 9.8. The correlation between the two ratings in the subsample was .32 (p< .01, df=93), suggesting that range restriction may have occurred in the original sample.

Constuct validation

For the rural clients, the score on the MCAS-SR had a high inverse correlation with the global score on the Brief Symptom Inventory (Spearman's rho=−.59, df=286, p<.001). The correlation between the SF-12 MCS score and the MCAS-SR score was also high (Spearman's rho=.61, df=286, p<.001).

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study indicate that the MCAS-SR is a reliable instrument that is acceptable and relevant to consumers. The consumers who participated in this study suggested that the instrument could be valuable in planning treatment and measuring progress. On the other hand, validating level-of-functioning measures is challenging. For example, case managers or other informants may have limited contact with consumers and thus may generate ratings on the basis of little information (

15). Although Patterson and colleagues (

19) observed and rated clients as they performed tasks such as counting money and making change, a person's performance under scrutiny may not be representative of everyday behavior.

A complementary approach, which we used in this study, is to examine construct validity by correlating the self-report measures with other scales (

35). As has been found in other studies of level-of-functioning instruments (

36), scores on the MCAS-SR were correlated with but certainly not identical to those on commonly used measures of symptoms and health status.

We found a modest relationship between consumer self-report and clinician ratings, as others have found (

30,

49). Homogeneity of the study population may have attenuated the correlation. Persons who frequently use involuntary psychiatric treatment have been shown to have low scores on the MCAS (

13,

14,

33), but it was not possible to include many such persons in our study. Additional research is needed to examine the utility of MCAS-SR in more diverse populations. The correlations between self-reports and interviewer ratings were higher than those between self-reports and the ratings of case managers and were similar to correlations reported by Wallace and associates (

15). The higher correlations in our study may reflect the fact that the interviews took place on the same day that clients completed the MCAS-SR.

Several additional level-of-functioning measures for clinicians are available, including the Life Skills Profile used in Australia (

50,

51), the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales used in Europe (

52), and the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (

2,

53,

54). However, these instruments lack consumer self-report measures comparable to the MCAS-SR (

2).

Given the importance of consumer participation in the delivery of mental health services (

20), the MCAS-SR fills a significant need. The instrument is brief—one double-sided page—and the vast majority of consumers can complete it without assistance. It could easily be used in telephone interactive voice response systems for clients who have poor vision or who are illiterate. The self-report data produced by the MCAS-R can stimulate fruitful discussions between consumers and clinicians (

25), track treatment progress, assist in rate setting, and aid in determining level of disability.