Integrating services and service systems has been a policy concern in the human service arena since the 1960s, beginning with the War on Poverty and its Model Cities Program (

1,

2,

3). This concern has been important in mental health policy for almost as long, having origins in the community mental health movement as well as in the current community support movement (

4,

5,

6). Integration of services and systems has been viewed as a strategy for meeting the multiple needs of persons who seek services in a fragmented service system. A good example is the effort to serve homeless persons who have severe mental illness and substance use disorders. The federal task force that developed

Outcasts on Main Street (

7) called for a demonstration program to coordinate services for this target population and in 1993 led the federal Center for Mental Health Services to undertake the ACCESS program (Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports) (

8,

9).

Background

Fragmented service systems

A premise underlying many recent government and foundation initiatives is that most community-based services are not organized to meet the needs of persons with serious mental illness. Many terms have been used to describe this situation in the fields of both children's and adult's services, including "fragmented care," "discontinuity of care," "buck passing," "nonsystem," "lack of coordination," and "revolving-door clients."

This fragmentation in service systems is considered to be a serious obstacle to the delivery of community-based care for people with severe mental illness (

4,

5,

10,

11,

12). Homeless persons, in particular, need a broad range of services and require specialized assistance from numerous health and social welfare agencies (

6). Meeting these needs is thought to be difficult when relationships between agencies are characterized by misinformation and mistrust due to infrequent contact, unfamiliarity, and conflicting organizational cultures (

13).

Defining systems integration

The literature defines systems integration in many ways. Some articles focus on the service delivery level and the interface between the consumer and the provider (

14). Others recognize that systems integration happens at different levels (

15). For the most part, systems integration involves the development of interagency partnerships that establish linkages within a system and across multiple systems to facilitate the delivery of services to individuals at the local level to improve treatment outcomes (

7).

System change strategies

The literature is equally uncertain about how systems integration is achieved. A number of strategies have been identified as reinforcing the linkages among agencies to facilitate service delivery (

2,

15,

16,

17). These include interagency coalitions; systems integration coordinators; co-location of services; interagency agreements or memorandums of understanding; interagency management information systems; pooled or joint funding; uniform applications, eligibility criteria, and intake assessments; interagency service delivery teams; flexible funding; and special waivers.

Previous research

Evaluations of the effects of systems integration have had mixed results. Most have shown that efforts to integrate systems lead to improvement in the system's organization and performance (

18,

19,

20,

21) but little or no improvement in clinical outcomes and quality of life for clients (

22,

23,

24,

25). Although several studies have demonstrated significant cross-sectional relationships between systems integration and client well-being (

13,

22,

26,

27,

28,

29), only one study (

27) empirically evaluated an intervention designed to improve systems integration.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Program on Chronic Mental Illness sought to enhance the integration of services through the development of central mental health authorities in nine large U.S. cities. Although the study showed that systems of care in the participating cities became more integrated as a result of the initiative (

18) and that continuity of care improved as a result of greater availability of case management services, no impact was observed on outcomes such as symptoms, social relationships, and quality of life (

22). A subsequent report from this program suggested that the lack of a significant relationship between systems integration and client outcomes might be due to variability in the quality of case management services provided across the study sites, which could have masked the impact of systems integration on outcomes (

30).

The ACCESS program

The ACCESS program was a five-year demonstration program sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (

9). It was the largest, longest, and most methodologically rigorous effort that has been undertaken to assess the effect on client outcomes of efforts to improve systems integration.

The purpose of the ACCESS program was to evaluate the impact of implementing system change strategies that would foster collaboration and cooperation among agencies and reduce the fragmentation of service systems in communities that also provided intensive outreach and assertive community treatment services. Twenty-five states submitted proposals in 1993, and nine were selected through a peer review process to receive a total of about $17 million a year to participate in the study. Each state had identified two communities that were comparable in terms of the estimated number of homeless persons with mental illness, local housing stock, population size, median income, and type of community (rural, urban, or suburban). These 18 sites, listed in

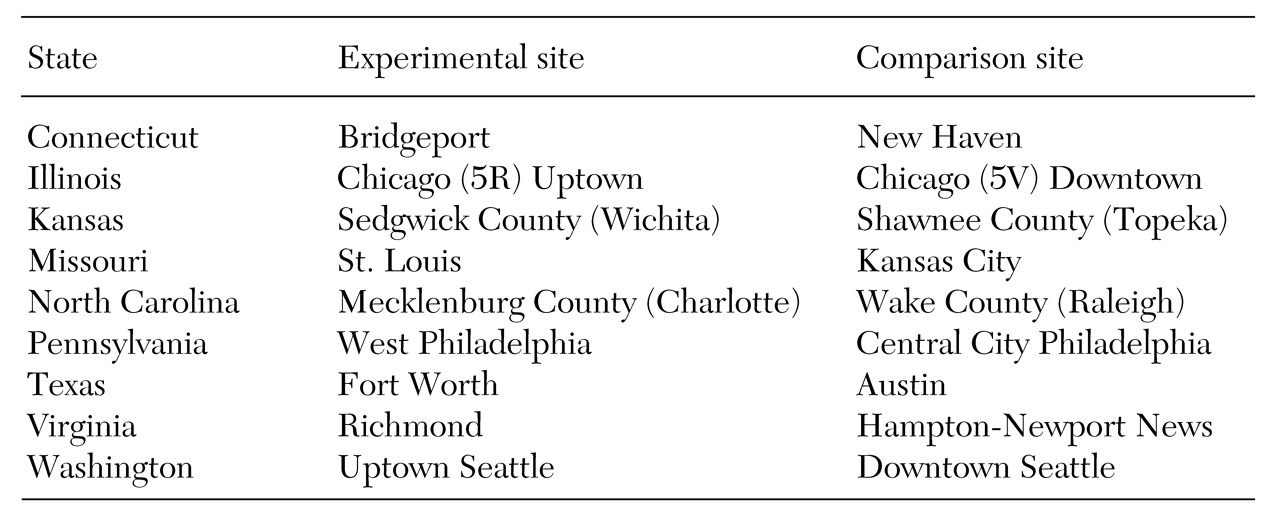

Table 1, were located in 15 of the largest cities in the United States. At each site, cohorts of about 100 homeless persons with severe mental illness were to be recruited and engaged in treatment each year for four consecutive years, for a total of about 400 persons at each site.

One site in each state was designated by the toss of a coin to be that state's experimental site and thus to receive about $250,000 to implement system change strategies for integrating mental health, substance abuse, housing, primary care, and income maintenance services into a more coherent system of care for the target population. The experimental sites selected the strategies they would undertake to implement integration and received technical assistance during the second year of the program to help them implement these strategies. In addition to paying for staff to provide overall coordination for implementing the strategies, the funds supported the work of interagency coalitions, the development of a strategic planning process, and specialized training and technology to help implement the strategies.

To allow for uniform recruitment of clients and to ensure that all study participants received similar clinical services, each of the 18 sites received about $500,000 a year to conduct intensive outreach to homeless persons in the community and to provide assertive community treatment to the participating clients. Using these funds, each site established at least one assertive community treatment team that consisted of outreach workers, case managers, and specialized staff. Resources were also used to hire program staff to oversee the project. The importance of providing this level of resources across the 18 sites was reinforced by the post hoc explanation of the findings from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's program, which argued that efforts toward system change had to be coupled with consistent treatment interventions (

9,

30,

31).

Evaluation study

Systems integration was operationalized in two ways for the purposes of the evaluation. The first, referred to as overall systems integration, was related to organizations in a community that provided mental health and substance abuse treatment, health care, income support, and housing. The second type of systems integration was referred to as project-centered integration and involved only the relationship between the ACCESS grantee organization and other organizations. For both types of systems integration, the evaluation focused on the relationship among all these organizations in terms of joint planning, shared resources, and shared clients.

Two core questions were identified for the evaluation. First, does implementation of system change strategies lead to better integration of service systems? Second, does better systems integration lead to better outcomes for homeless persons with severe mental illness?

The ACCESS evaluation also tested six hypotheses: that providing funds and technical assistance would result in higher levels of overall systems integration; that it would result in higher levels of project-centered integration; that, regardless of random assignment, implementing system change strategies would result in higher levels of both types of systems integration; that providing funds to implement system change strategies would result in greater improvement in client outcomes; that more complete implementation of a greater number of strategies would result in improved client outcomes; and that change in the level of systems integration across cohorts, regardless of random assignment or implementation of system change strategies, would be associated with improvements in client outcomes.

Data collection

The data for this study were collected from 1994 to 1998 from agencies that provided mental health, substance abuse, housing, primary care, and income maintenance services to homeless persons with serious mental illness; from participating clients at each of the 18 sites in the ACCESS demonstration; and from annual visits to the 18 sites. In all, data were obtained from about 1,000 service agencies and multiple cohorts, for a total of more than 7,000 enrolled clients. This combined effort has produced the largest single database ever assembled to address the relationships between change strategies, systems integration, and client outcomes.

Conclusions

Findings from the evaluation are presented in the next two articles in this issue, and conclusions and policy implications are offered in the final article. These articles address only a part of the overall evaluation of the ACCESS program, which also included qualitative data about the political, economic, and social contexts of the nine states and 18 sites over the study period. Data were also collected on how the system change strategies were implemented, on obstacles to their implementation, and on the grantees' perceptions of the impact of the demonstration program in their communities. Some results have already been disseminated (

32). Further analyses are being conducted, and results will be published.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded under interagency agreement AM-9512200A between the Department of Health and Human Services, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Center for Mental Health Services, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center as well as through a contract between the Center for Mental Health Services and ROW Sciences, Inc. (now part of Northrop Grumman Corp.) and subcontracts between ROW Sciences, Inc., and the Cecil A. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Maryland, and Policy Research Associates of Delmar, New York.