This article summarizes the main findings of the ACCESS (Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports) program, which evaluated the effectiveness of systems integration strategies in addressing the problem of homelessness among persons with severe mental illness, and presents lessons for policy makers. This is the last in a set of four articles in this issue of Psychiatric Services. In combination, these articles provide an overview of the evaluation of the ACCESS program.

The ACCESS program provided funds and technical support to nine randomly selected sites in nine states to implement strategies for promoting integration of service systems. These experimental sites, along with nine comparison sites in the same states, also received funds to support assertive community treatment to assist 100 clients per site per year in four annual cohorts (

1). Data on the implementation of system change strategies were collected through annual visits to the sites (

2). Data on changes in systems integration were obtained from interviews with key representatives of relevant organizations in each community (

3). Client outcome data were obtained at baseline and three and 12 months later from 7,055 clients across the four cohorts at all sites (

4).

Summary of findings

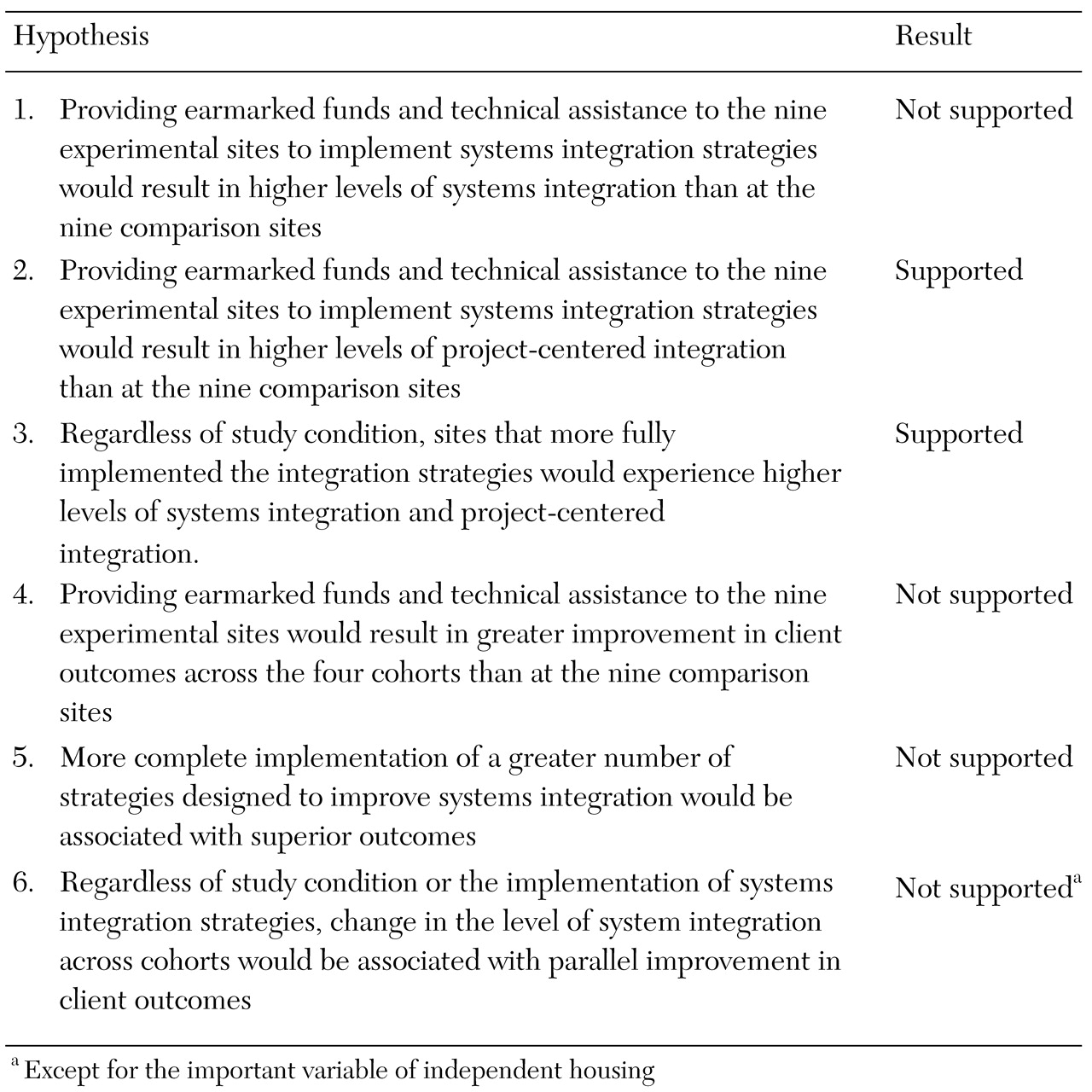

Table 1 lists the six hypotheses that were central to the evaluation of the ACCESS program and indicates whether or not each hypothesis was supported by the evaluation. Details are presented in other articles (

3,

4).

The evaluation that was described only briefly in the first of the four articles (

2) but that has been described in more detail elsewhere (

5) assessed the feasibility of implementing the various strategies of the ACCESS demonstration. The study showed that systems integration strategies could be implemented as intended only if significant additional technical assistance was provided. The evaluation also showed that when technical assistance and substantial resources were provided by the federal government, all the sites were able to implement outreach and intensive case management programs that were moderately faithful to the assertive community treatment model. Interestingly, most sites retained these services for one year after the federal resources were withdrawn (

6).

Other nonexperimental data showed that on average, clients at all sites and in all cohorts showed improvement, as would be expected for clients of assertive community treatment programs (

7). In addition, analyses of preliminary data from the ACCESS program demonstrated that street outreach is an effective way of contacting individuals who are more severely ill and those who are less motivated (

8). Furthermore, termination of assertive community treatment after only one year was not associated with any subsequent deterioration in clinical outcomes after about six months (

9).

In addition, clients at sites that had greater improvements in systems integration were more likely to achieve stable housing (

4). This finding was consistent with the results of a previous cross-sectional examination, which showed that clients at sites with higher levels of systems integration were more likely to be independently housed 12 months after enrollment in assertive community treatment (

10).

In policy terms, although the theory that links systems integration and individual outcomes was supported for independent housing, across-the-board efforts to implement systems integration strategies cannot be recommended as a means of achieving desired client-level outcomes. Although implementing systems integration strategies might be advocated to achieve other objectives, such as a more efficient system, it cannot be recommended as a way of promoting individual-level outcomes.

Conclusions

The ACCESS evaluation demonstrated that it is possible to enhance project-centered integration. The evaluation also showed that specific strategies for enhancing project-centered integration exist and can be helpful in increasing integration in a community, and that enhanced integration can help homeless persons with severe mental illness escape from homelessness.

The evaluation did not show that these strategies promote better client outcomes above and beyond what can be achieved with good clinical services, such as assertive community treatment. Nevertheless, the findings offer some hope of progress in dealing with the seemingly intractable problem of homelessness among persons with severe mental illness.

Much was learned from this elaborate and well-implemented demonstration program and its evaluation. The most important lessons are summarized below:

• Systems integration can be improved.

• Important, practical strategies for systems integration can be identified and implemented.

• Implementation of systems integration strategies takes time and requires both technical assistance and resources.

• Implementation of systems integration strategies will not necessarily improve integration on a systemwide level but is likely to improve integration between a designated mental health agency and other agencies in the same community.

With considerable resources and effort, policy makers might use specific strategies to achieve integration. These strategies are more likely to be successful within the mental health system than across human services agencies broadly.

In addition:

• Systems that are better integrated have significantly better housing outcomes. (Although this cross-sectional finding is encouraging, the ACCESS demonstration did not provide evidence to suggest specific strategies that would produce this result. Some communities are just better integrated for a variety of reasons.)

• Investment in systems integration cannot be expected to produce desired clinical outcomes.

• Mental health authorities should be encouraged to provide substantial resources to develop housing, outreach, and assertive community treatment teams.

In summary, the systems-integration solution to the problem of homelessness and mental illness that the authors of

Outcasts on Main Street(

11) had hoped for was only partly realized in the ACCESS program. Extensive and targeted efforts to promote systems integration do not produce desired social and clinical outcomes at the individual client level. However, the ACCESS program has provided sound empirical answers to questions that were first raised more than 30 years ago (

11,

12,

13,

14). It has taught us many lessons and has kept the problem of homelessness in the consciousness of a nation that would otherwise be in danger of forgetting about it.

Furthermore, the ACCESS program has demonstrated the feasibility of implementing a range of direct services capable of reaching out and engaging thousands of homeless people who have severe mental illnesses and who often are living on city streets. These individualized services improve both the physical health and the mental health of these people and can help in moving them into independent housing. What remains is to provide the resources for outreach and intensive clinical care as well as housing and rental subsidies to sustain the lessons of the ACCESS program.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded under interagency agreement AM-9512200A between the Department of Health and Human Services, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Center for Mental Health Services, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center as well as through a contract between the Center for Mental Health Services and ROW Sciences, Inc. (now part of Northrop Grumman Corp.) and subcontracts between ROW Sciences, Inc., and the Cecil A. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Maryland, and Policy Research Associates, Delmar, New York. The ACCESS National Evaluation Team includes Lisa Creatura, M.P.A., Mary Lou Dogoloff, Matthew Johnsen, Ph.D., Monique Mercer, M.P.A., Laura Samberg, M.A., Joseph Sonnefeld, M.A., and Ann Worthen, B.A.