Measures

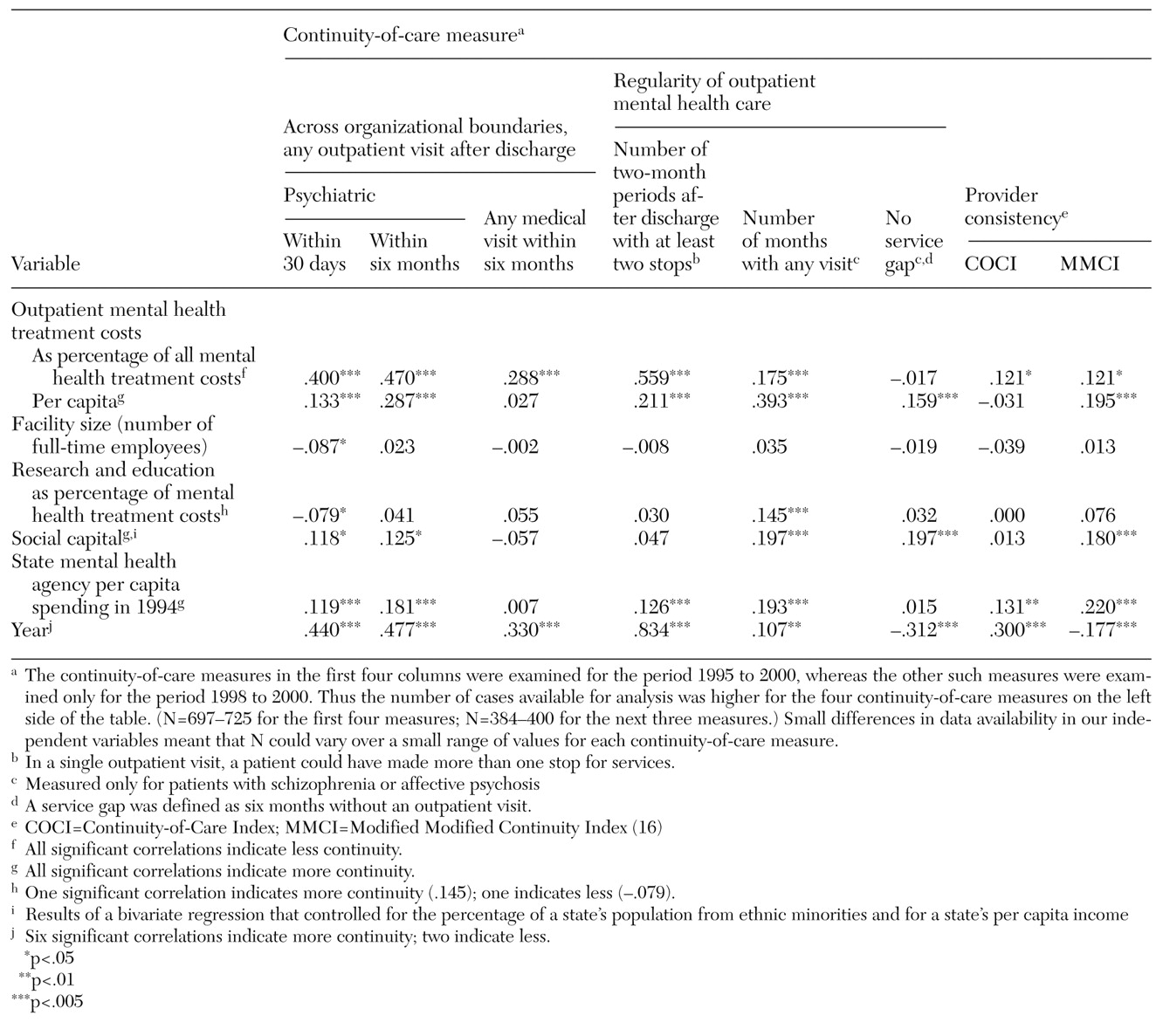

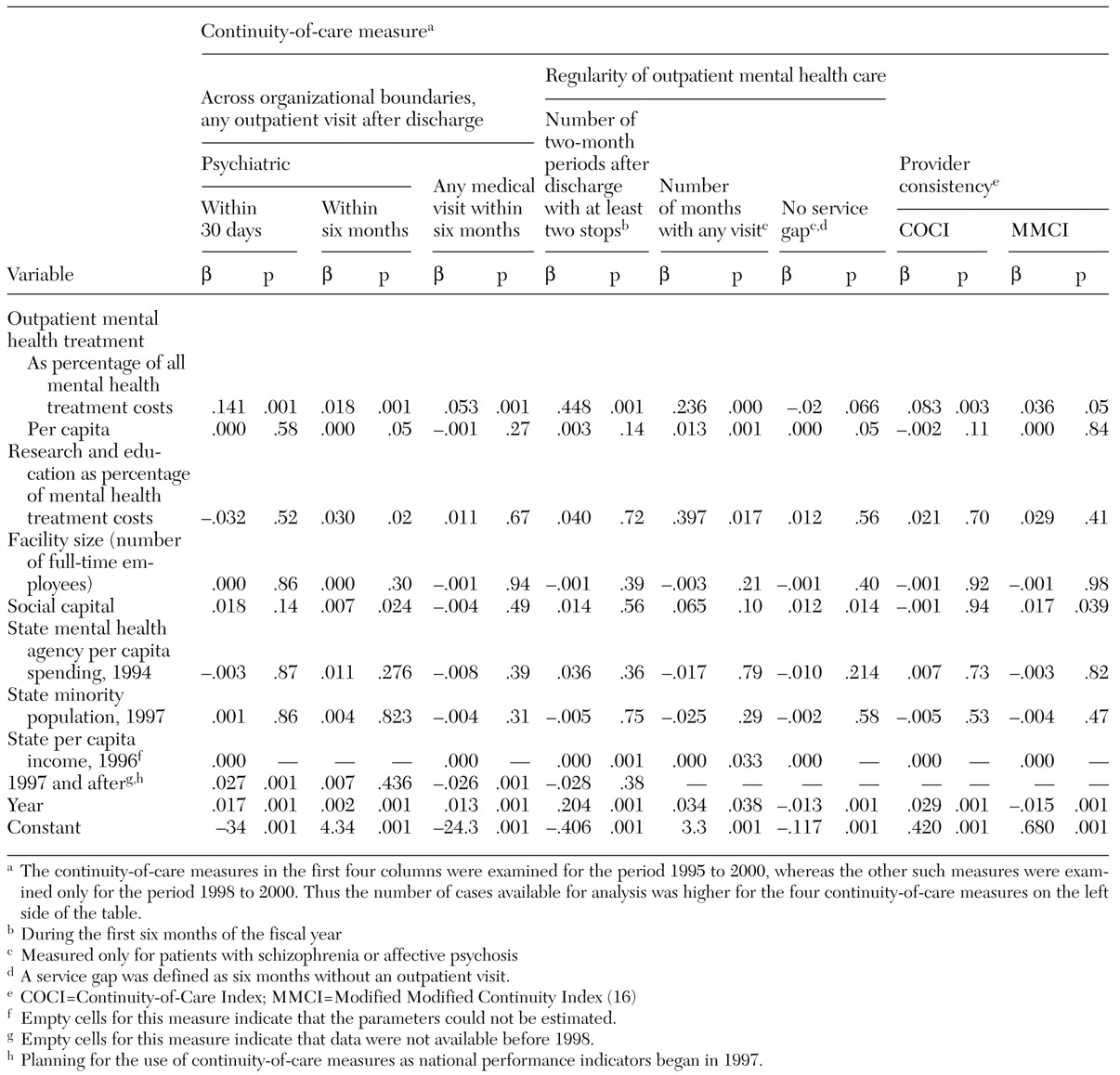

Continuity-of-care measures. We classified continuity-of-care measures in three domains: continuity across organizational boundaries, regularity of care, and provider consistency.

Continuity across organizational boundaries was examined with three measures: whether a veteran who was discharged from an inpatient psychiatry program received any mental health outpatient treatment during the first 30 days after discharge; whether a veteran who was discharged from an inpatient psychiatry program received any mental health outpatient treatment during the first six months after discharge; and whether a veteran who was discharged from an inpatient psychiatry program, and who also had a secondary medical diagnosis, received any medical outpatient care in the six months after discharge.

Regularity of care was examined with three measures. The first was the number of two-month periods in the six months after discharge from inpatient care in which a veteran had two or more outpatient mental health visits (range, 0 to 3). In contrast to the previous measures, which were based on an index inpatient stay, the two other regularity-of-care measures reflected continuity of outpatient services for severely mentally ill patients—that is, those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or affective psychosis—who had at least two outpatient mental health visits in the first six months of each fiscal year. These measures addressed the number of months during a six-month period in which a veteran had at least one visit (range, 0 to 6) and whether a veteran went six months without any outpatient mental health care—that is, whether the veteran dropped out.

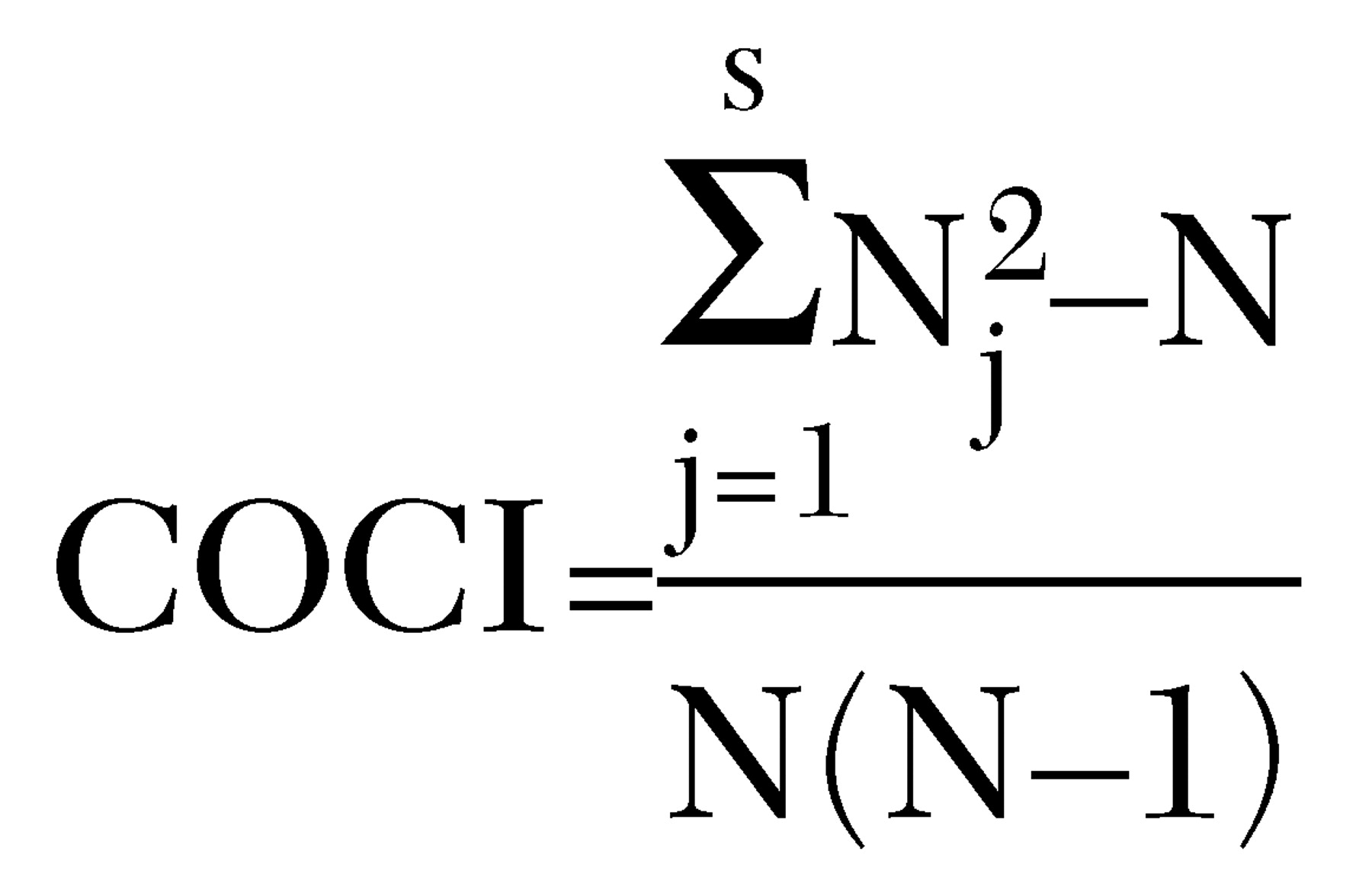

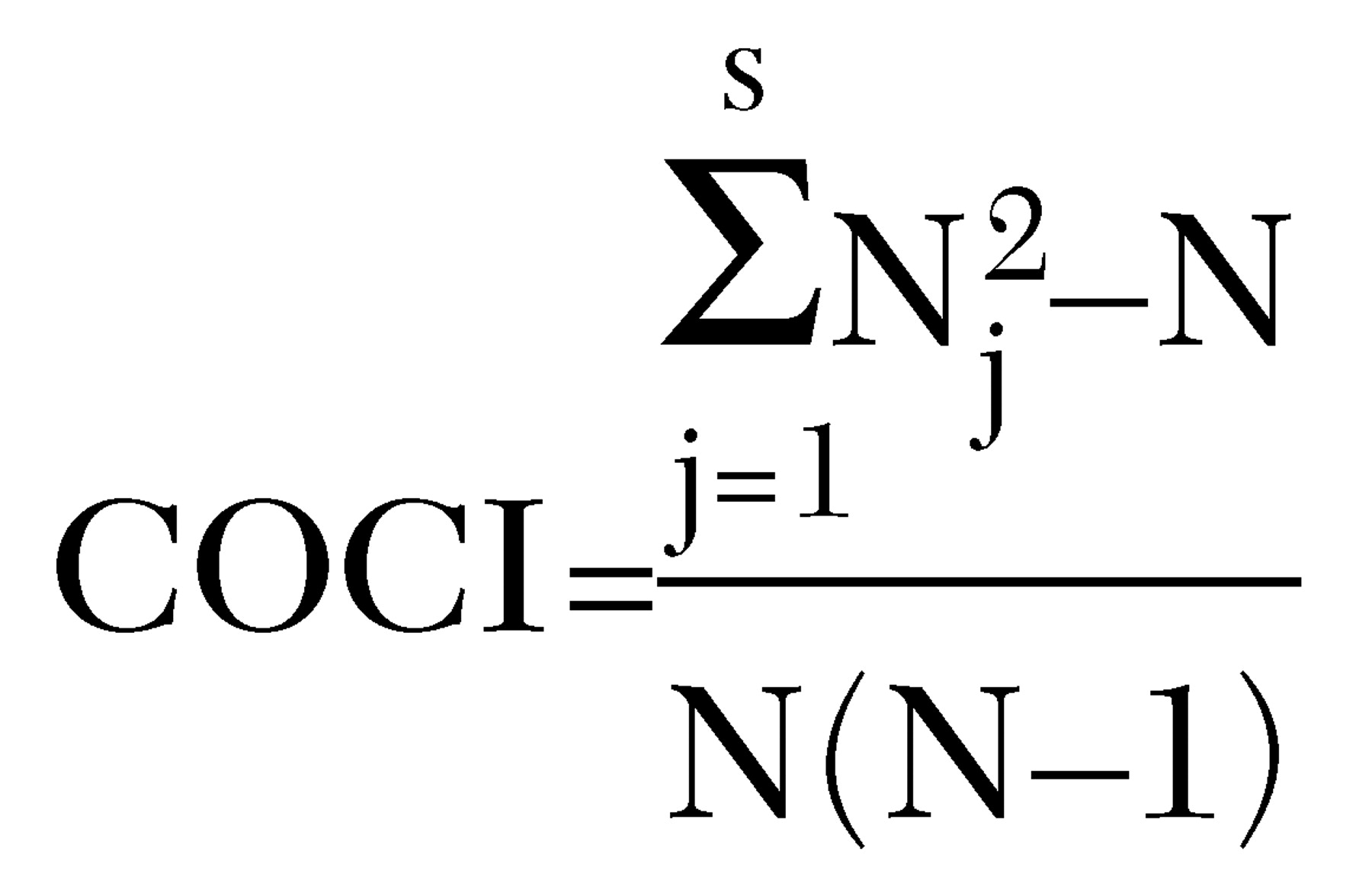

Two composite indexes were used to examine provider consistency; these also pertained to severely mentally ill clients who had least two outpatient visits. The indexes were the Continuity-of-Care Index (COCI) and the Modified Modified Continuity Index (MMCI), which are based on the number of visits and the number of providers. The COCI uses the following formula (

16):

where N equals the total number of visits and N

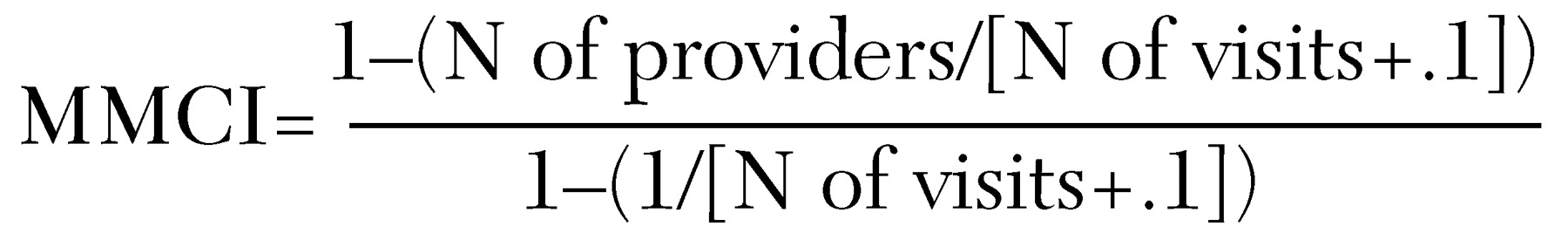

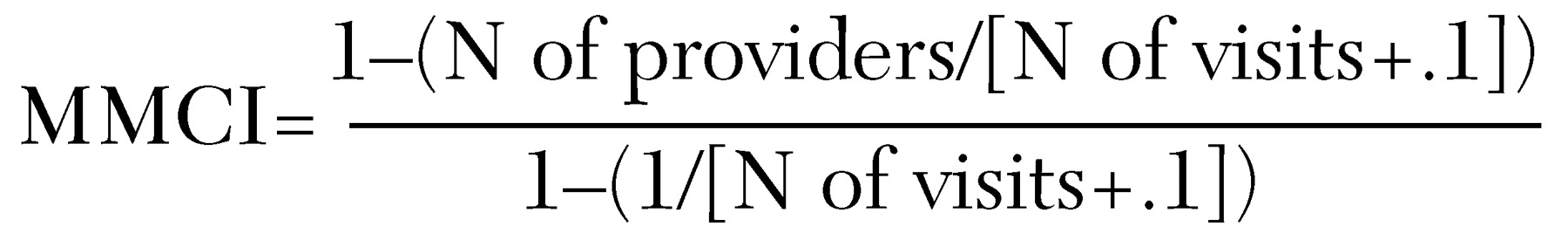

j is the total visits to the jth provider. This measure generates a continuity-of-care score from 0 to 1, where 1 represents more visits with fewer providers and 0 represents few visits with each of several providers. The second index, the MMCI, is calculated as follows (

28):

This index takes a different approach to calculating a measure based on a scale of 0 to 1, but, as with the COCI, 1 represents more visits with fewer providers and 0 represents no visits.

All continuity-of-care measures were risk adjusted to minimize biases imposed by variability in sociodemographic characteristics across medical centers. Characteristics used for risk adjustment included age, race, gender, diagnosis, marital status, distance of residence to the nearest VA medical center, disability status, psychiatric diagnosis, and medical comorbidity. Further details of the analytic methods and risk factors are presented elsewhere (

10,

11).

Institutional factors. We hypothesized that several institutional factors assumed to be under managerial control would be associated with continuity of care.

First, we hypothesized that greater continuity would be associated with greater per capita expenditures on outpatient mental health care and more emphasis on outpatient care, as reflected by a higher percentage of total mental health expenditures on outpatient care. These measures were adjusted for inflation and local wage rates.

Second, we hypothesized that the degree of academic emphasis, as reflected by the proportion of mental health expenditures devoted to research and education, would be associated with less continuity of care, for two reasons: academic institutions have task priorities in addition to clinical care, and care is often provided by inexperienced and transient trainees.

Although the VA's National Mental Health Performance Monitoring System (

11), beginning in 1995, circulated information on continuity-of-care measures, these measures had no official status until 1998, when they began to be used to evaluate the job performance of top VA administrators. A third hypothesis was that planning for the use of these measures as national performance indicators, which began in 1997, would be associated with greater continuity of care. Therefore we created a variable that had a value of 1 for the years 1997 to 2000 and a value of 0 for other years.

Finally, we hypothesized that larger hospitals, as measured by the number of full-time employees, would have less continuity of care because larger organizations are more complex and may have greater difficulty in coordinating services as needed to maintain high levels of continuity of care, particularly between inpatient and outpatient services.

Environmental measures. We examined two aspects of the environment of VA medical facilities. The first was the degree to which veterans had access to health services outside the VA. As an indicator of the availability of such resources we used the per capita expenditures by each state's mental health agency (

25), which has been shown to be associated with reduced use of VA services (

29,

30). We expected that VA continuity of care would be lower in states in which more mental health resources were available.

The other environmental factor was social capital at the state level. Social capital, which refers here to the level of civic involvement or social trust, has been shown to foster greater cooperation in problem solving (

23,

31). We hypothesized that social capital would be associated with greater continuity of care. For example, a study of homeless people with severe mental illness in 18 U.S. cities showed that greater social capital was associated with greater system integration, greater likelihood of client contact with a public housing agency, and greater likelihood of becoming housed (

24).

The social capital scale had 13 items, including the number of club meetings attended in the past year, the number of community projects worked on in the past year, the number of times volunteer work was done in the past year, general belief that other people are honest, and the proportion of adults in each state who voted in the 1988 and 1992 elections (

23). The data came from telephone surveys administered to representative samples of civilians across the United States (

23). These measures were standardized and averaged to generate a state-level measure.

Two other measures were used as controls for our analysis of social capital: the percentage of each state's population from ethnic minorities and the per capita income of each state. Putnam (

23) has shown that more ethnically mixed and lower-income states have lower social capital, and our interest was in the effect of social capital independent of these factors.