Patient aggression occurs in a variety of health care settings (

1), at a high cost to both individuals and organizations (

2). According to Lanza and Carifio (

3), it is very important to answer the question of who or what caused an assault. One suggested cause of aggression is aggressive patients' perceptions of their victim's behavior (

4,

5). In few studies, however, have patients been asked about their perceptions related to aggression.

Harris and Varney (

6) interviewed male psychiatric patients being treated in a psychiatric maximum security unit. Patients involved in aggression were asked about the causes of assaultive behavior. Patients gave no response for 24 percent of the assaults and responded that they did not know the reason or perceived no particular reason for 15 percent. Responses for the remaining 61 percent of the assaults were classified as being teased or being bugged (21 percent), staff provocation (12 percent), building up of tension or being upset (5 percent), being ordered to do something (5 percent), refusal of a request (4 percent), voices or delusional orders (3 percent), crowding (3 percent), anger at ward rules (2 percent), and reaction to a sexual approach (.5 percent).

Crowner and colleagues (

5) asked 40 patients—28 men and 12 women—from a special psychiatric ward for violent patients why an assault had happened. Both the assailant and the victim were asked why the assault had occurred. Twenty-six percent of the assailants refused to be interviewed or did not give an explanation for the assaults. Another 5 percent of the assailants denied any involvement in the assaults. Reasons for assaultive behavior included playing (12 percent); being provoked by insults, name-calling, spitting, or "nastiness" (12 percent); wanting the other patient to stop doing something (9 percent); threatening or insulting another patient because of anger (9 percent); bizarre responses (6 percent); retaliation (6 percent); feeling threatened (5 percent); struggling for an object (4 percent); sexual provocation (3 percent); wanting the victim to do something (3 percent); feeling body space had been invaded (1 percent); and perceiving the victim as out of control or crazy (1 percent) (

5).

Love and Hunter (

7) gathered information about patients' opinions of the causes of violence and suggestions for solutions. Participants in this study were male forensic patients who identified two main themes related to causes of aggression: social hazards of forensic environments and violence-provoking staff-patient interactions. Social hazards included inflexible rules, crowding, lack of resources, mixture of gravely disabled patients with patients who have character disorders, the need for power—that is, establishing territory, pecking order, and personal safety—and alliances. Violence-provoking staff-patient interactions included busy staff who do not consider patients' unmet needs, the manner in which privileges are granted and revoked, staff's changing medications to punish patients for speaking up, and staff's granting favors or attention unequally.

Morrison (

8) conducted a qualitative study at a metropolitan public hospital, collecting data over nine months. When a violent incident occurred, Morrison asked nursing staff and several male and female patients to describe what happened and why it happened. The most frequent response to the question "Why are you violent?" was "to get people off my back." Other quoted reasons presented were "to build my rep" (reputation) and "I fight because of the stigma of being small. People pick on me a lot." The final group of reasons given were to gain control over others, to gain positive rewards, to get medication as needed, to get into seclusion in order to sleep, to force staff to comply with wishes, and because staff were too busy.

Ilkiw-Lavalle and Grenyer (

9) interviewed 29 psychiatric patients about aggressive incidents in which they had been involved. Three main causes of aggression were identified: patient illness factors (33 percent), interpersonal conflict (36 percent), and limit setting (31 percent). Patients suggested the following interventions to reduce aggression: improved medication management (4 percent), improved handling of interpersonal conflict (64 percent), and more flexibility in limit setting (32 percent).

Because patients' perceptions of what causes aggression and what can be done to prevent aggression are poorly understood, members of the subcommittee for prevention and management of disruptive behavior interviewed individual patients from August 1 to September 30, 1998, about their views of causes and of possible interventions for assaultive behavior. "Assault" was defined in this study as fighting or attacking another. This study is one of very few reporting patients' suggestions for interventions to prevent aggression.

Methods

Sample

The sample was drawn from patients at a Veterans Affairs medical center in the Midwest (N=92). Two participants (2 percent) were female; 75 (82 percent) were Caucasian, 11 (12 percent) were African American, and one (1 percent) was Hispanic; for five (5 percent), race was not identified. Most participants—77, or 84 percent—had a psychiatric diagnosis. The rest of the participants had a medical diagnosis.

Procedure

After the investigators received approval from the facility's institutional review board, data were collected by the subcommittee task force. To obtain a sample of both inpatients and outpatients, these procedures were followed: On inpatient units, a list of the patients' names was obtained and every fifth patient was asked to participate in the study. In the outpatient areas, the first 21 outpatients who arrived for appointments on given days were asked to participate in the study. Patients were informed that their treatment at the hospital would not be influenced by their decision to participate in the study. The 92 patients (71 inpatients and 21 outpatients) were interviewed after giving verbal consent.

A number of participants in previous studies had refused to answer researchers' questions about assaults: 24 percent of Harris and Varney's (

6) sample and 26 percent of Crowner and colleagues' (

5) sample. Therefore, it was thought that participants would be more willing to be interviewed if they were not directly asked whether they had been involved in an assault. Questions were worded so that the participants would not necessarily be giving information about themselves.

The interview concerned both patient-to-patient and patient-to-staff aggression and was conducted in this way: The participant was asked, "Have you been present when two patients fought each other?" Those who answered "yes" were then asked, "What causes patients to fight?" and "What might help prevent patient fights?"

Next, the participant was asked, "Have you been present when a patient attacked a staff member?" For those who answered "no," the interview was terminated. Those who answered "yes" were asked, "What causes patients to attack staff?" and "What actions might help patients not attack staff?"

Participants often gave more than one response to questions, which resulted in an extremely large and varied group of causes and possible interventions. Therefore, the first author divided the responses into common categories, the third author reviewed the categories, and disagreements were discussed until these two authors reached agreement. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the frequency of participants' perceptions.

Results

Witnesses to aggression

Of the 92 participants, 40 had never witnessed patient-to-patient or patient-to-staff aggression, and 52 had witnessed one or both types of aggression.

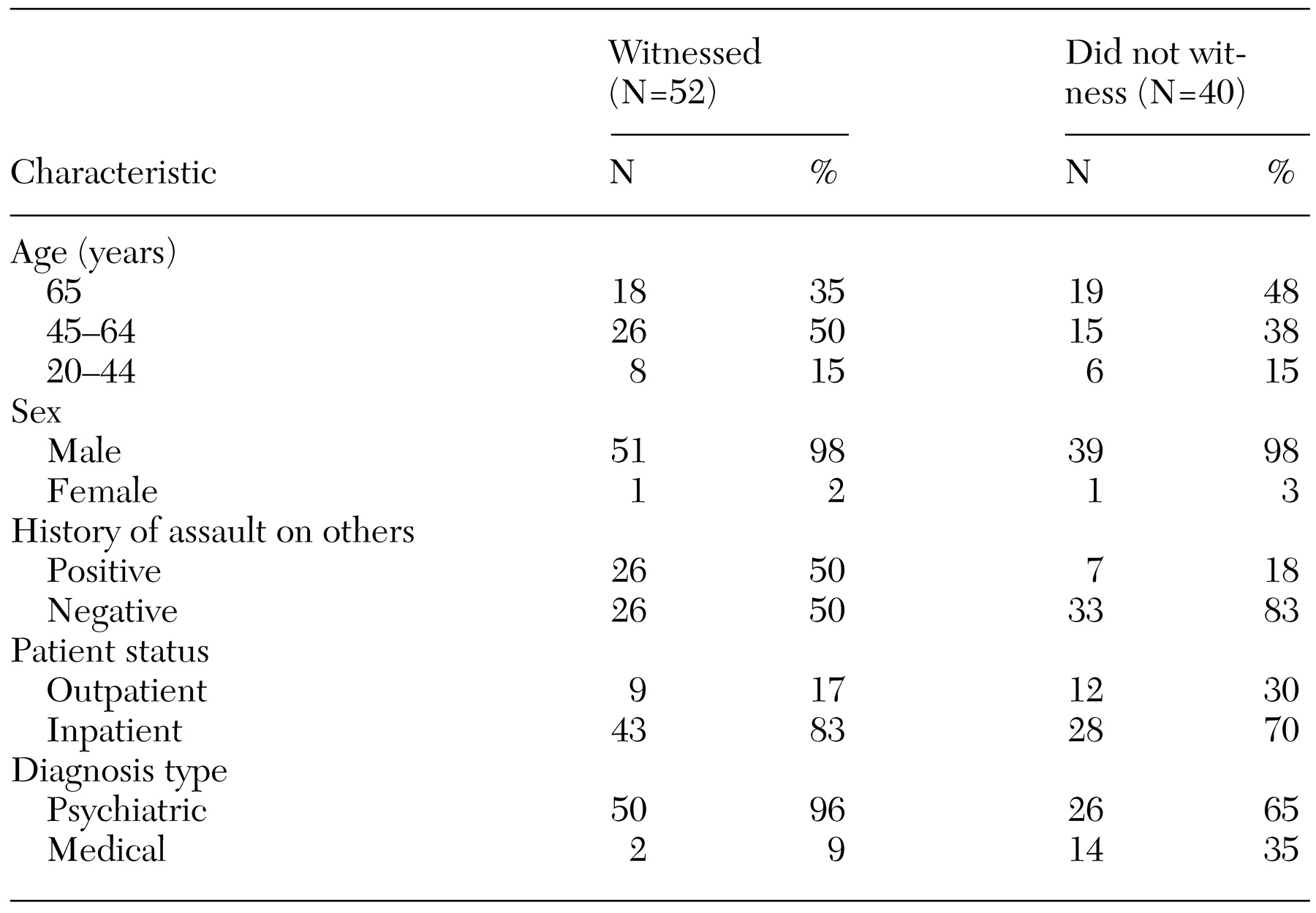

Table 1 compares the characteristics of participants who had witnessed an assault with those of participants who had not. The two groups of veterans were similar in age and gender. Most of the veterans in both groups were inpatients. Half of the participants in the group that had witnessed violence had a history of assault themselves, as documented in the patient records. In contrast, only seven (18 percent) of the 40 participants who had not witnessed an assault had a history of assault. Fifty of the 52 participants who had witnessed aggression had a psychiatric diagnosis, whereas only two participants with a medical diagnosis had witnessed aggression.

Causes of aggression

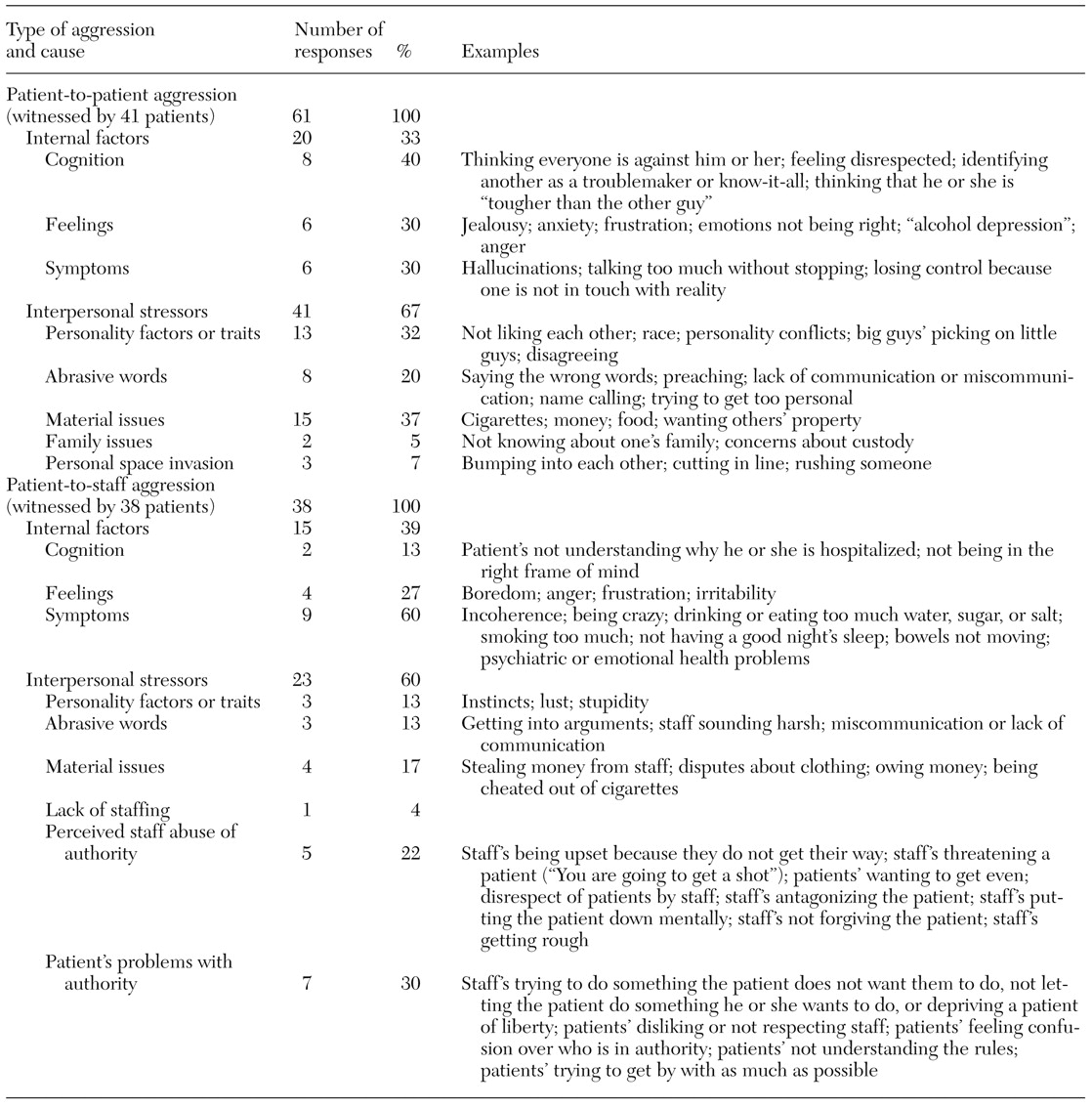

As shown in

Table 2, the 41 participants who had observed patient-to-patient aggression identified 61 causes. These causes were then classified as internal factors and interpersonal stressors. Internal factors included cognition, feelings, and symptoms. Interpersonal stressors included personality factors or traits, abrasive words, material issues—issues about money or personal possessions—family issues, and personal space intrusion.

As can also be seen in

Table 2, the 38 participants who had witnessed patient-to-staff aggression described 38 factors that caused such aggression. The responses were classified into internal, or individual, factors and interpersonal stressors. Internal factors included cognition, feelings, and symptoms. Interpersonal stressors consisted of personality, abrasive words, and material issues. Unlike the interpersonal stressor category for patient-to-patient aggression, these interpersonal stressors did not include family issues or physical aggression. The three causes added to the interpersonal stressors for this group were lack of staffing, perceived staff abuse of authority, and patient problems with authority.

Interventions for aggression

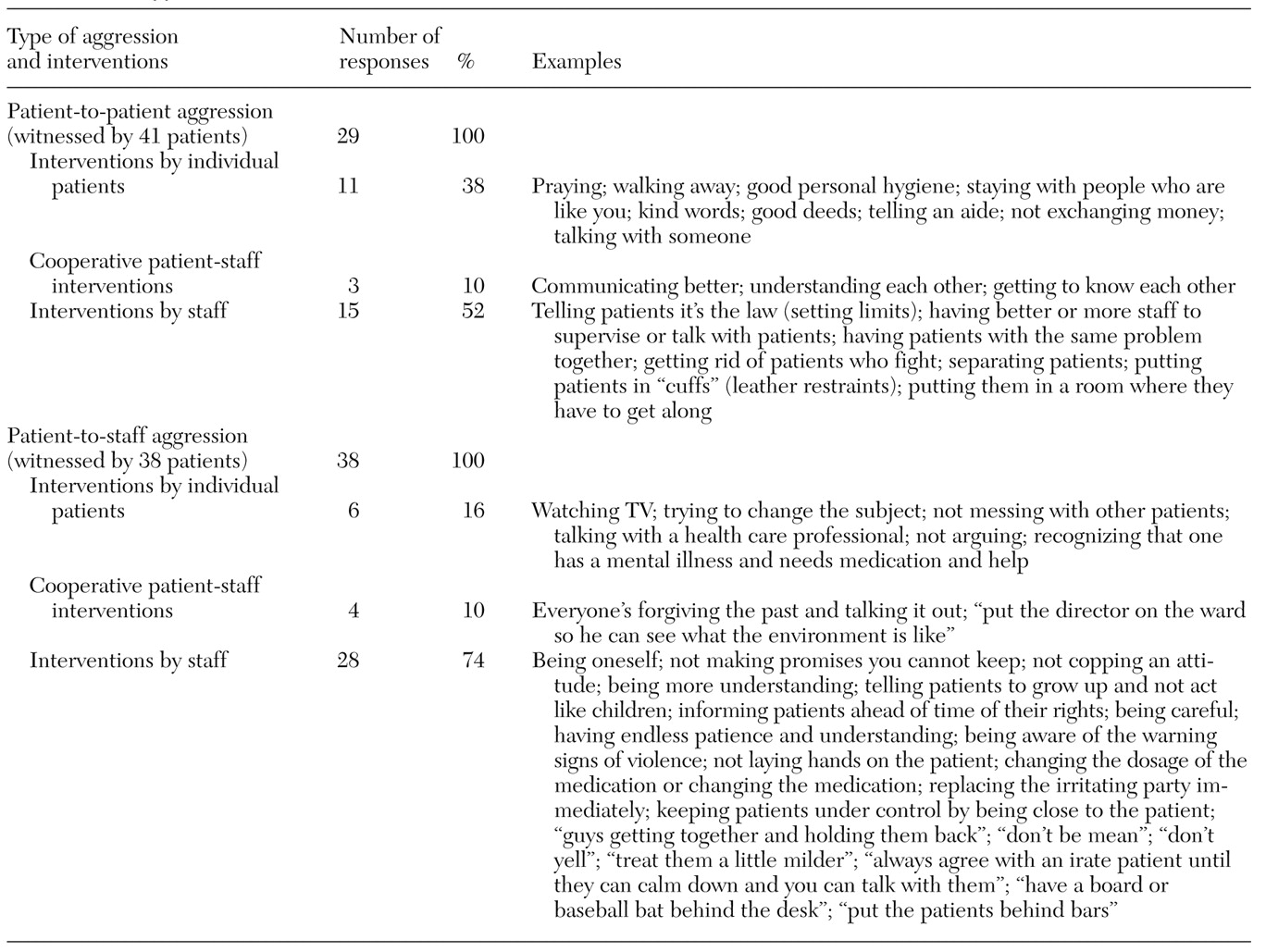

As shown in

Table 3, the 41 participants who had witnessed patient-to-patient aggression identified 29 interventions, including those for both staff and patients, to prevent such aggression. Interventions were divided into three categories: individual patient, cooperative patient-staff, and staff interventions.

As also shown in

Table 3, the 38 participants who had witnessed patient-to-patient aggression identified 38 interventions to prevent it. Once again, these interventions were separated into individual patient, cooperative patient-staff, and staff interventions.

Discussion and conclusions

The patients' viewpoints in this study support previous research related to patients' perceptions of the causes of aggression. The patients described nearly all the causes of aggression identified by patients in studies conducted by Crowner and colleagues (

5), Harris and Varney (

6), Love and Hunter (

7), Morrison (

8), and Ilkiw-Lavalle and Grenyer (

9). Patients in this study, however, did not report several causes that were described in other research: sexual provocation, staff's favoring certain patients, staff's giving some patients more attention, patients' desire to get into seclusion, and the way privileges are given.

Although Love and Hunter's (

7) methods were different from those used in the current study, there are some similarities between the perceptions of their forensic patient participants and the veterans in our study. Both groups described crowding, unmet needs, and the mix of patients as factors leading to aggression. The responses of the two groups differed in that the veterans but not the forensic patients identified psychiatric symptoms as playing a part in violence. The forensic patients talked explicitly about power and control; the veterans did not discuss these issues, even though these concepts may have been implied in some of the veterans' comments.

Although participants in this study did not call it verbal intervention, they discussed the importance of the patient's talking either to staff or to another patient. Ilkiw-Lavalle and Grenyer also found that participants in their study thought that improved staff-patient communication would help reduce aggression. Morrison (

8) found that effective verbal diffusion—similar to our concept of verbal intervention—was seldom used in the practice site she investigated, because nonprofessional staff thought that the use of physical restraints was more efficient than verbal diffusion. Other staff, therefore, might not value verbal intervention.

Patients in other studies spoke about the use of chemical or physical interventions—changing medications, giving patients proper medication, and placing them in "cuffs." The participants in our study also noted that staff sometimes threatened them with chemical intervention. Although these participants recognized the importance of treating symptoms, they wanted chemical intervention to be used appropriately and also recognized that physical restraint was sometimes needed.

Limitations of the study include the sample characteristics, most of which limit the generalizability of the study's findings. The participants in the study were all U.S. veterans, most of whom were Caucasian (75 percent) and male (98 percent). The number of participants who declined to participate in the study was not collected. Thus it is difficult to determine whether the sample is representative of the population being studied.

We agree with Ilkiw-Lavalle and Grenyer's recommendation that staff supervision and training highlight the need for understanding patients' perceptions. The information in this study about patients' perceptions of the causes of and interventions for aggression can be used to educate staff on the importance of taking the time to use verbal intervention that might prevent the need for chemical and physical intervention. Knowledge about patients' perceptions makes empathic listening more likely (

3). If staff are able to listen, verbal intervention is more likely to be effective. Moreover, Smoot and Gonzales (

10) found that training staff in empathic communication skills resulted in fewer assaults. This information can be added to the current classes being conducted at this VA health care system. In addition, the facility staff are currently learning a patient-centered rehabilitation approach for working with veterans. Implementation of this approach may decrease rates of assault at the facility.

The participants identified patients' actions as well as staff actions that could prevent violence. This information could be shared in patient group discussions to teach patients additional skills to deal with potentially violent situations.

The results of this study suggest several research questions for future studies. When interviewed about the causes of aggression and appropriate interventions, do nonforensic patients and forensic patients give similar responses? Do patients and staff give similar responses? Do assault rates decrease if staff are supported in using verbal intervention?

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karen Davis, M.A.L.S., John Grandstaff, and Lydia Cisco, B.A., for their help in conducting the literature search, and Glenda Ledford for her help in data collection.