Compared with privately insured persons, those who are uninsured report poorer physical and mental health (

5,

6,

7). They also are more likely to have a serious psychiatric problem, including substance abuse or dependence (

8,

9,

10). Uninsured persons are significantly less likely to receive mental health services (

10,

11), especially from specialized professionals (

11,

12). However, one study showed no significant differences between uninsured and privately insured persons in outpatient mental health service use (

8).

Discussion and conclusions

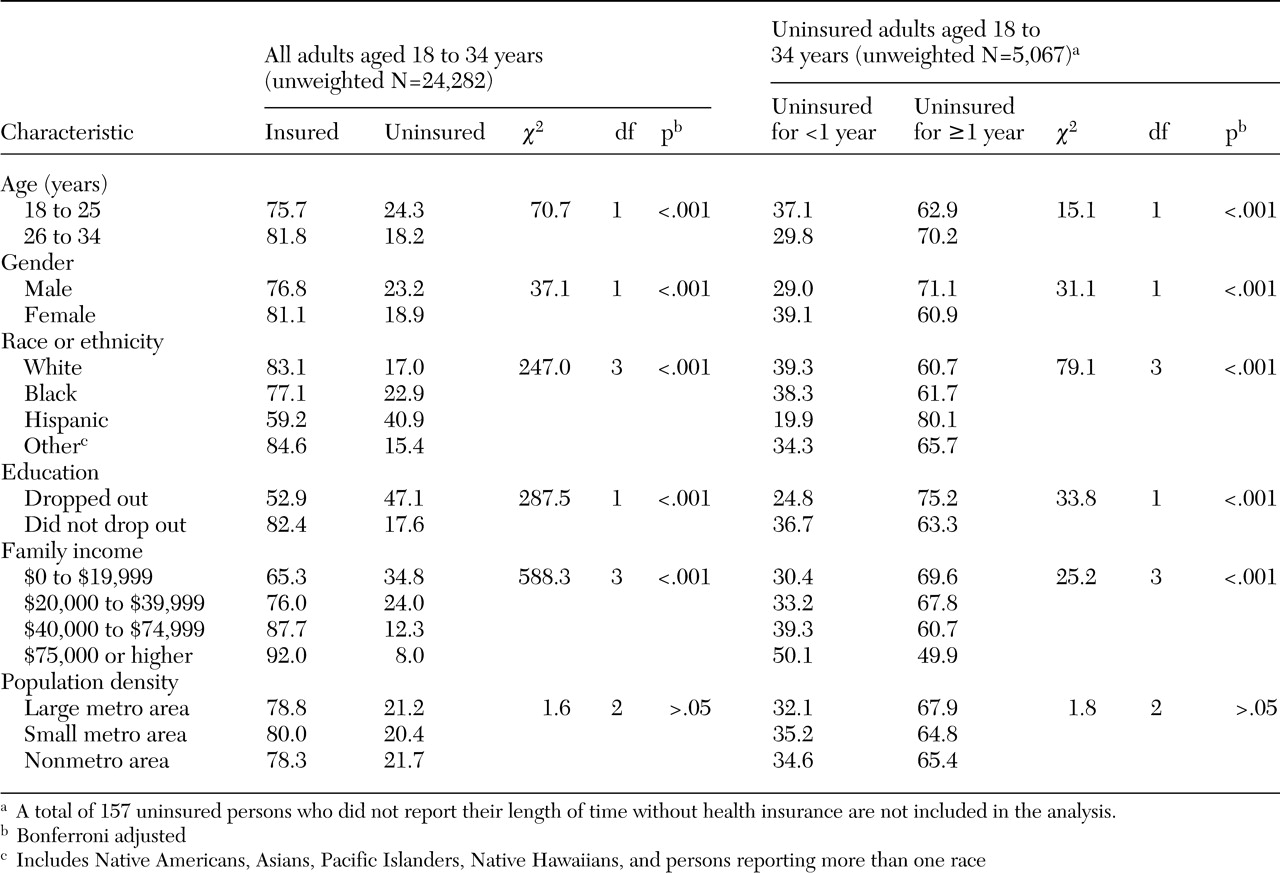

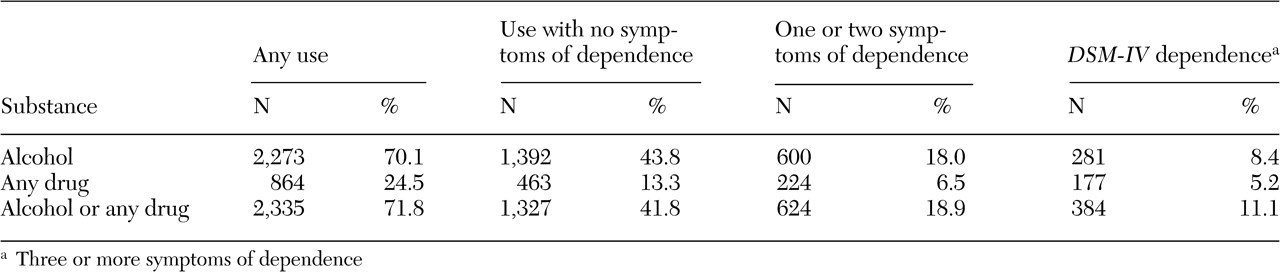

We found that in 1999 two-thirds of uninsured Americans aged 18 to 34 years lacked health insurance coverage for at least a year. Of this sustained uninsured group, 11 percent met criteria for alcohol or drug dependence in the previous year. Prevalence estimates of drug dependence in the 1999 NHSDA appear to be slightly higher than those in the 1990-1992 National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). Between 2 percent and 3 percent of individuals aged 15 to 34 years in the NCS and between 9 percent and 12 percent of those who used drugs met

DSM-III-R criteria for drug dependence in the past year (

27). In the 1999 NHSDA, 4 percent of all persons aged 15 to 34 years and 16 percent of all past-year drug users aged 15 to 34 years manifested past-year drug dependence. This difference might be partially attributable to variation in interviewing procedures. For example, the NHSDA used audio computer-assisted self-interviewing for sensitive substance use questions.

A majority of people with alcohol or drug use disorders do not receive substance abuse services (

28,

29,

30,

31). The National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey found that 10 percent of Americans aged 18 years or older who had alcohol abuse or dependence in the past year received alcohol abuse services, and 9 percent of those reporting drug abuse or dependence received drug abuse services (

28). In our uninsured sample, 11 percent of alcohol-dependent individuals used alcohol abuse services and 15 percent of drug-dependent individuals used drug abuse services.

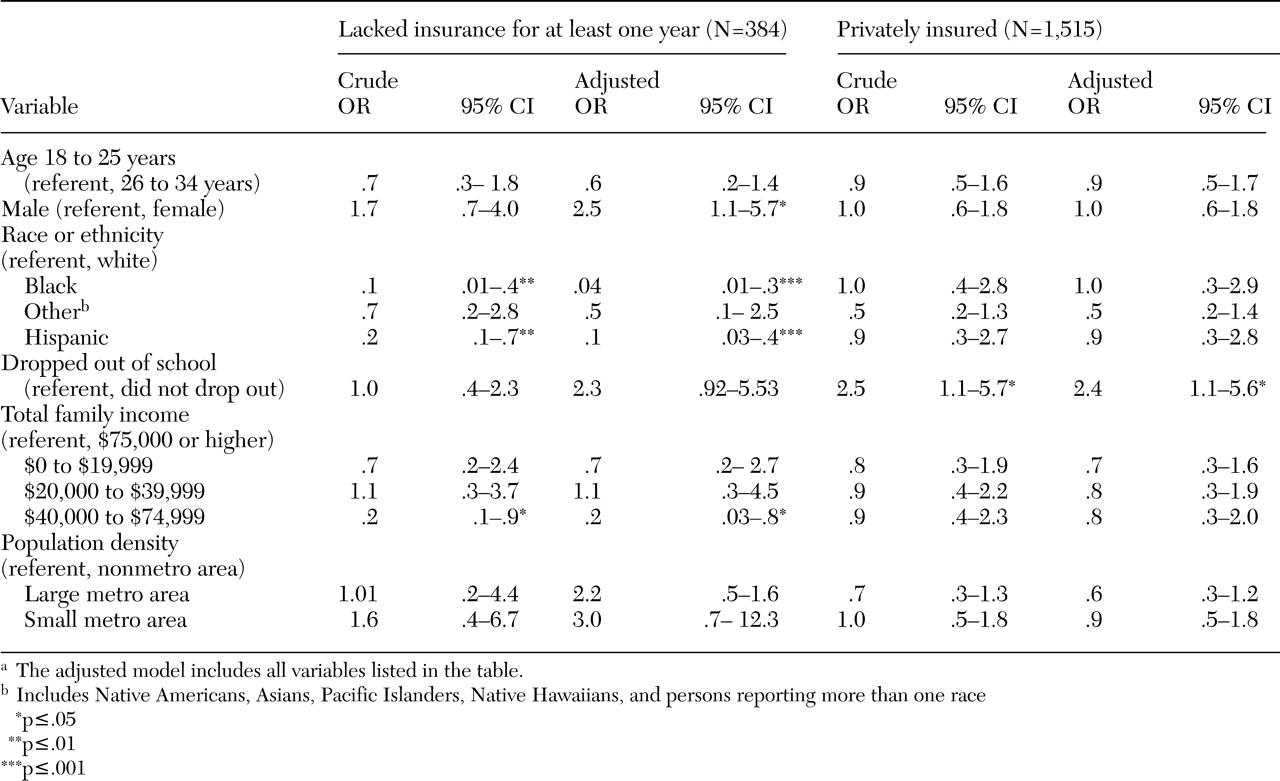

Our findings suggest that young uninsured women who are alcohol or drug dependent are less likely than their uninsured male counterparts to use substance abuse services. Studies have suggested that child care, domestic responsibilities, and social stigma have constrained women's use of such services and that available treatment programs may tend to address men's needs more adequately than those of women (

32,

33,

34,

35,

36).

Uninsured Hispanics and blacks also may underutilize substance abuse services. Studies have revealed a lower rate of service use among Hispanics and blacks compared with whites (

17,

37,

38,

39,

40). Compared with whites with substance abuse or mental health service needs, blacks have less access to care and a greater unmet need for care (

38). Among those in need of substance abuse or mental health services, Hispanics are more likely than whites to report a delay in receiving care, lower satisfaction with care, and lower rates of receiving active treatment (

38).

Some culture-related factors may explain these findings, at least in part. Hispanic drug users appear to be more likely than white users to say that they do not seek drug abuse treatment because they do not perceive a treatment need, because of their reluctance to acknowledge their addictions, or because of their discomfort with the prospect of being separated from their families (

17,

18,

19). Black drug users are more likely than white users to have an unfavorable view of addiction treatment and to perceive that they have no need for it (

17,

18).

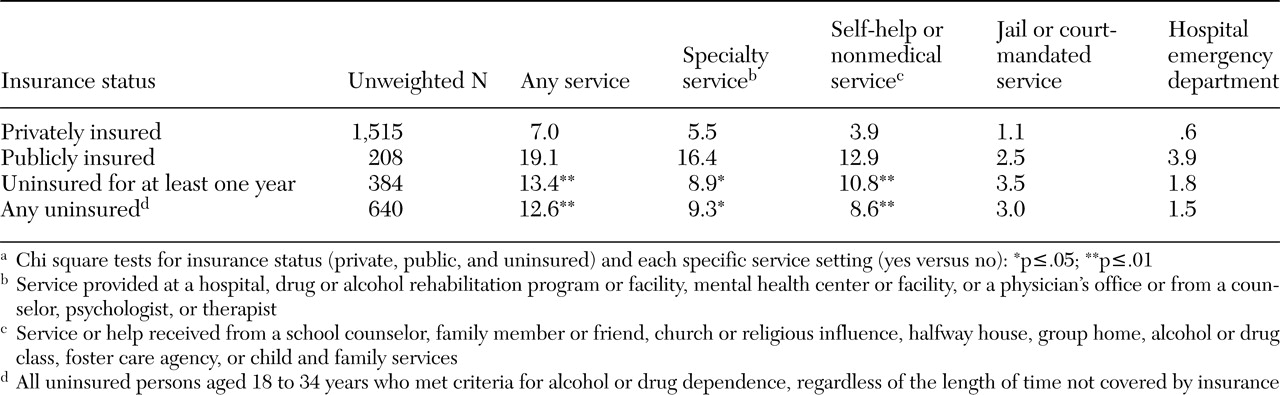

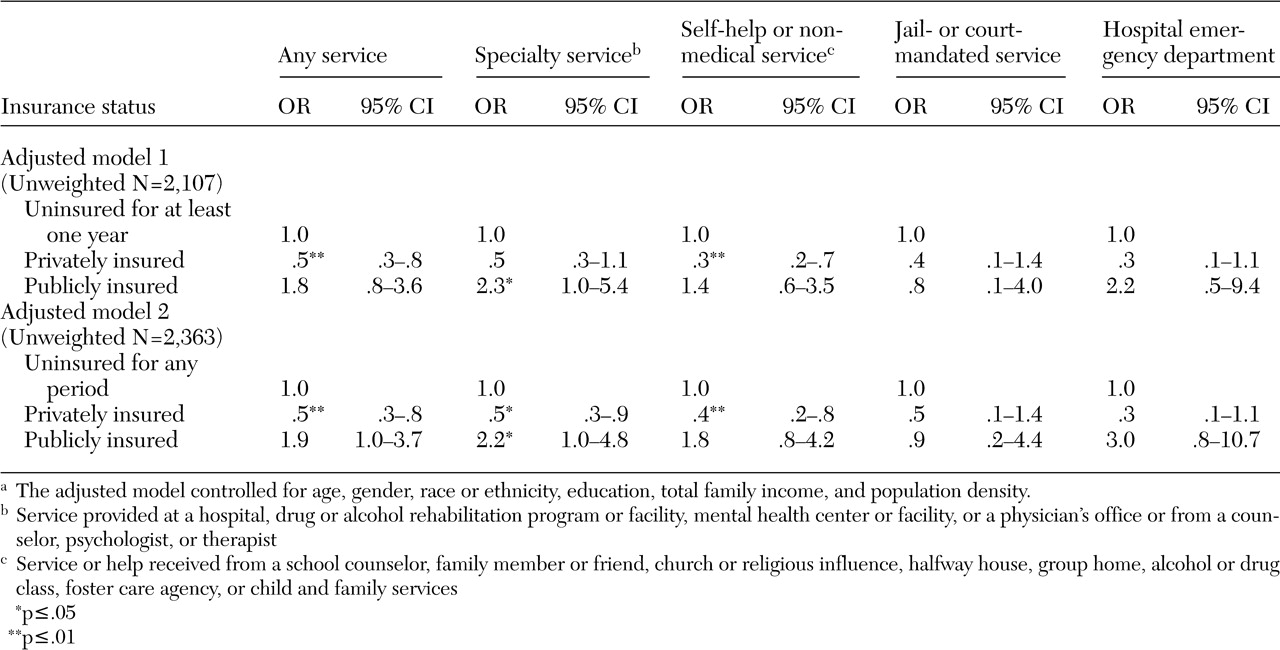

Contrary to other studies, our study found that uninsured persons had a higher rate of use of any substance abuse service than privately insured persons, particularly services from the self-help and nonmedical sectors. Wells and colleagues (

10) found that uninsured persons had a lower rate of use of any substance abuse or mental health service than privately insured persons and those with Medicaid. Differences in study designs may account for this discrepancy. In other studies, service utilization was measured as any visit for either a substance use problem or a mental health problem (

8,

10,

13). We defined the use of a service specifically for problems related to alcohol or drug abuse.

In addition, we focused on a young, uninsured subpopulation that may include a subgroup of more severe substance abusers who need treatment, whereas other studies have examined individuals across different age groups (

10,

13,

41). The prevalence of a recent substance use disorder and serious mental illness is highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 years (

42). Uninsured persons have been found to be more likely than those with insurance to have substance abuse problems and other psychiatric disorders (

8,

9,

1041). Our finding of a higher prevalence rate of service use among uninsured persons may be partly explained by characteristics of our sample: more uninsured persons than privately insured persons were dependent on both alcohol and at least one drug. Studies have identified the severity of substance abuse and its related social consequences, such as involvement in the criminal justice system, as important correlates of service utilization (

43,

44,

45). Our data suggest that uninsured persons may be more likely than those with private insurance to receive substance abuse services through the criminal justice system or an emergency department. However, the small number of service users in our sample might have limited the power to detect the difference. Further investigations of variations in substance abuse service use by insurance status within key age groups are warranted.

Furthermore, many substance abusers resist treatment, probably because of the stigma associated with substance abuse (

46,

47). Privately insured individuals may not use treatment services covered by their employer-based insurance plans, because they want to handle the problem on their own or they deny having substance use problems or treatment needs because they fear potential negative consequences. Studies of health insurance claims data have found that surprisingly few privately insured individuals use substance abuse services (

48,

49). Schoenbaum and colleagues (

48) reported that only about .3 percent of 617,133 members covered by a private, employer-sponsored, managed behavioral health care plan used any substance abuse services, whereas 17 times as many members used mental health services. We found that privately insured persons were less likely than uninsured persons to use services from the self-help sector. Clearly, there is a need to better understand factors that explain the very low rate of service use by the privately insured population (

49).

One recent study found that privately insured persons were less likely than uninsured persons to enter alcohol treatment (

44). Privately insured problem drinkers appear to enter treatment at the point at which their alcohol-related medical problems become sufficiently prominent that their physicians intervene (

44). Our findings also are consistent with those of other studies showing that a majority of clients in substance abuse treatment facilities do not have private insurance as the expected source of payment (

15,

50,

51,

52). Data from these facilities show that treatment participation is significantly associated with initiation of drug use at an early age and with use of multiple drugs, dependence, and involvement in the criminal justice system (

43,

52). For many substance abusers, treatment initiation typically is facilitated by social institutions or social service agencies (

43,

51,

52).

Data for this study were from a cross-sectional survey and depended on respondents' self-reports, which may reflect some subtle biases, such as underreporting or recall bias, that confounded our results. Second, these findings should not be generalized to subgroups that are not covered by the NHSDA, including homeless individuals and those living in institutional group quarters. Third, the lack of assessment of the quality, timeliness, and patterns of substance abuse care obtained precludes further examination of these issues.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important implications for policy making and delivery of substance abuse services. Lack of health insurance is not a temporary condition to many nonelderly, uninsured Americans (

41,

53). Among persons who need treatment, those who are uninsured are less likely than those who are insured to report satisfaction with substance abuse care (

10), to maintain their treatment regimens (

15), and to receive treatment in residential programs that provide continuing support for their abstinence and recovery (

16).

Only a small number of the young, uninsured, substance-dependent persons in our study received any substance abuse service within a 12-month period. Underutilization of substance abuse services by Hispanics, blacks, and women is particularly deserving of attention from policy makers and researchers. Our findings highlight the importance of the self-help and nonmedical sectors in the delivery of substance abuse services for the uninsured population (

54) and suggest the need to better understand the adequacy of services provided in these sectors. Publicly funded programs play an important role in the provision of substance abuse and metal health care to socially and economically disadvantaged subgroups (

8,

9,

51). Expanding public insurance coverage to the young and uninsured population, or restructuring the means by which these services are supported, is likely to improve access to substance abuse services among substance-dependent young adults.