Treatment nonadherence has been identified as a frequent cause of relapse among patients with bipolar disorder (

1,

2). Scott and Pope (

3) have reported that one in three persons with bipolar disorder does not take at least 30 percent of the medication that is prescribed, and Guscott and Taylor (

4) have noted that the major reason for the discrepancy between efficacy and effectiveness in lithium treatment of bipolar disorder is poor treatment adherence. Commonly encountered reasons for medication nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder include negative personal attitudes toward illness, poor insight into illness, depressive or manic symptoms, side effects from medications, and comorbid conditions, such as substance use and personality disorders (

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11). Individuals who are younger, male, single, and unmarried are particularly likely to be nonadherent to medications (

1,

12,

13).

An emerging body of literature suggests that it is possible to enhance treatment adherence among patients with bipolar disorder (

3,

14). A majority of therapies that are known to be effective feature an interactional component between patients and their care providers or therapists (

14). However, a number of challenges remain in designing, testing, and implementing interventions that address the issue of nonadherence among patients with bipolar disorder. A clear understanding is still lacking of the features relating to treatment adherence that are amenable to possible change, such as patient characteristics and the patient-provider relationship. Additionally, it is possible that barriers to the care system may contribute to poor adherence, and these factors have received limited attention.

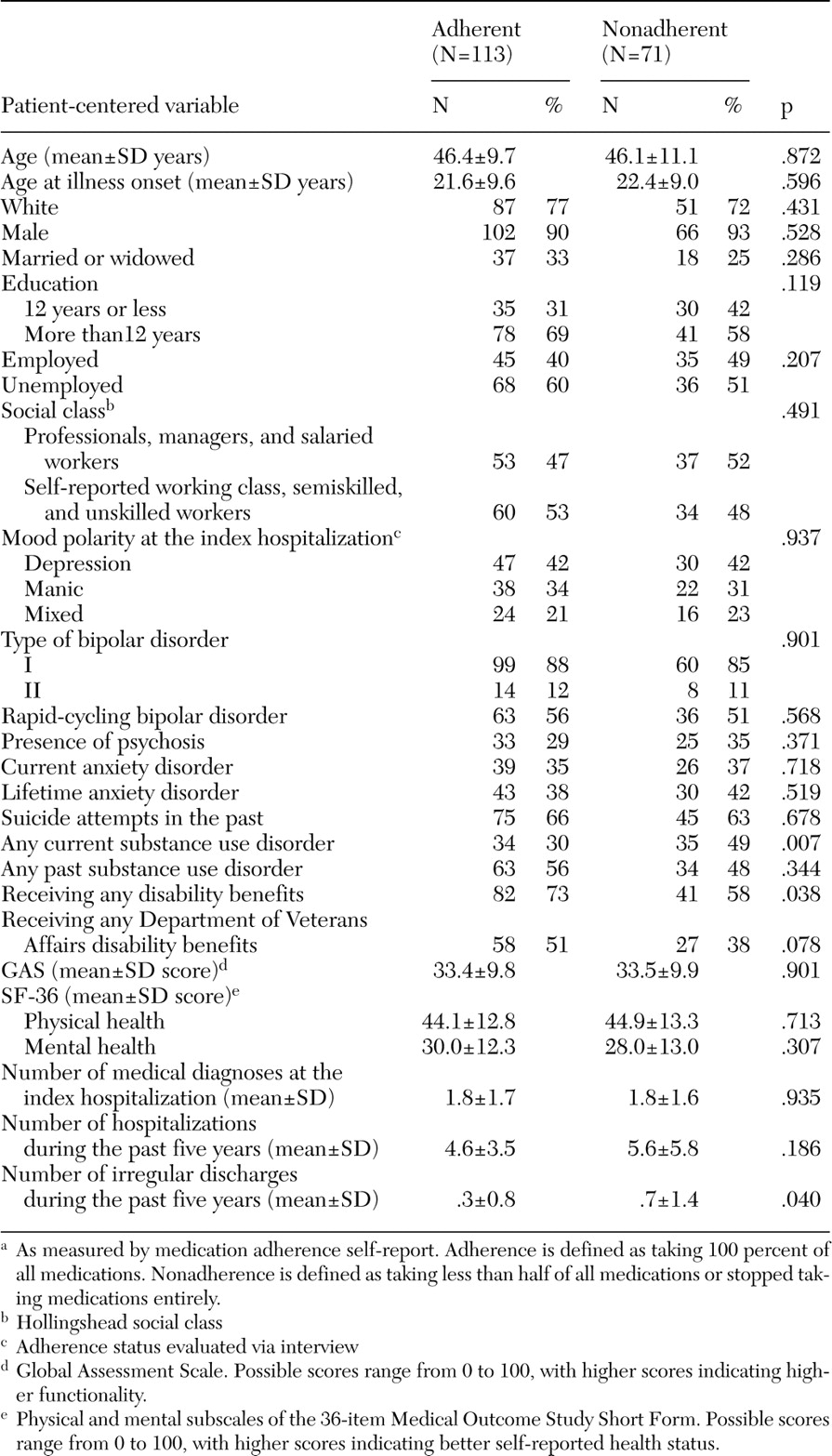

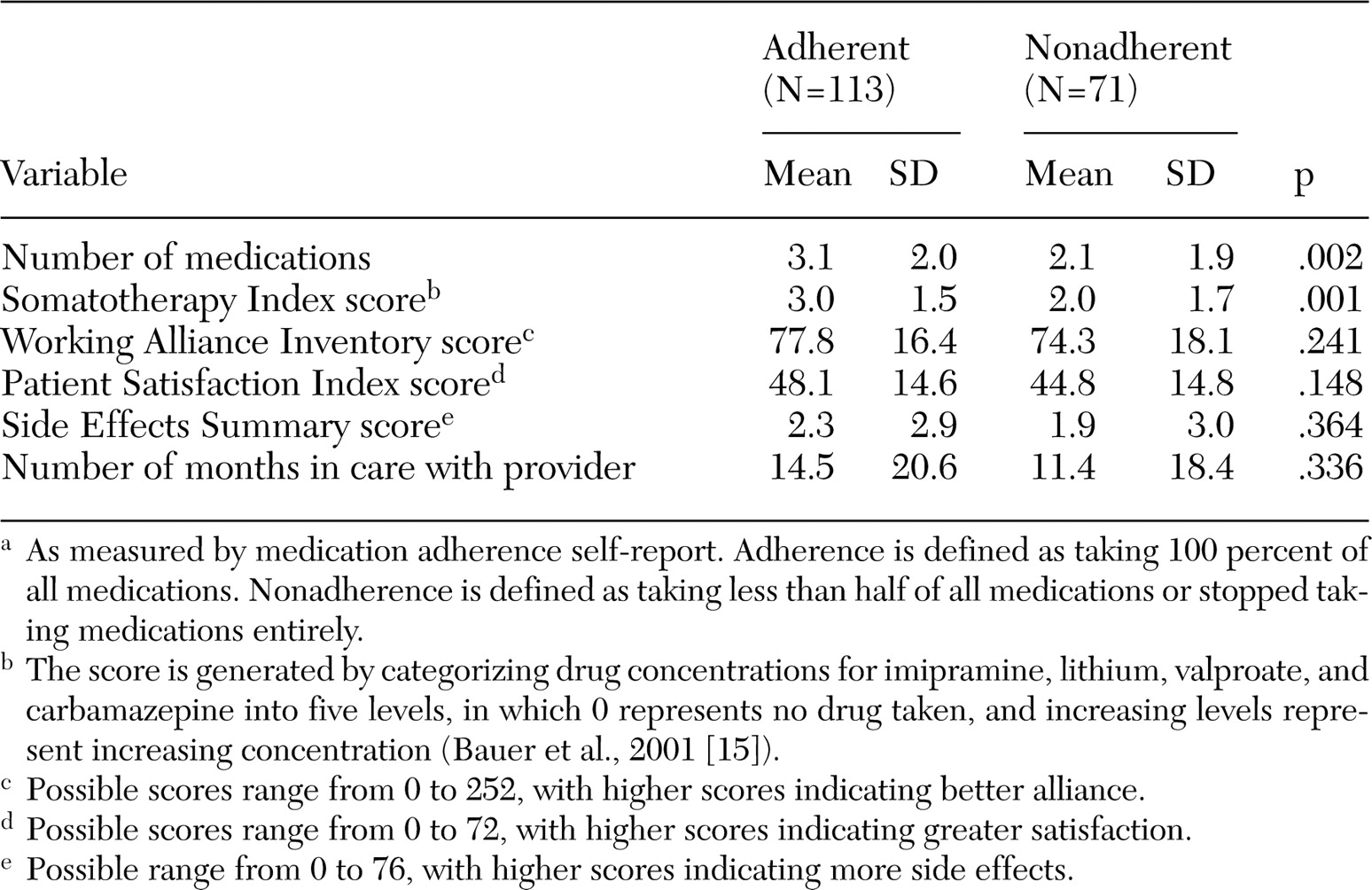

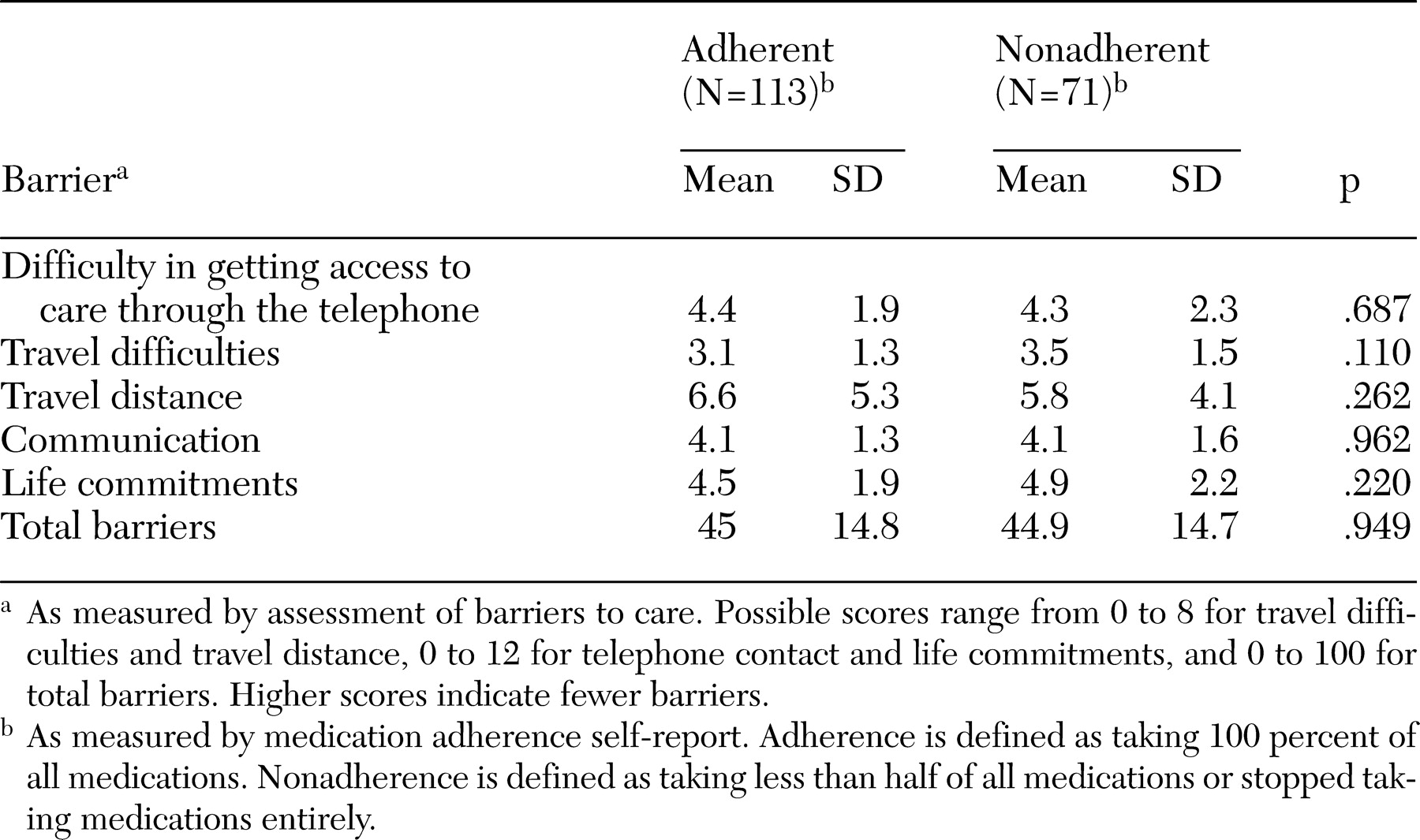

This article presents a cross-sectional analysis of patient characteristics, features of the patient-provider relationship, and barriers to care as they relate to self-reported treatment adherence among veterans with bipolar disorder. Data were collected before patients were randomly assigned to a multicenter trial. We hypothesized that specific features would be related to better treatment adherence: patient characteristics (fewer symptoms, overall better health status, higher functional level, female gender, and absence of substance use disorder), features of the patient-provider relationship (better treatment alliance, fewer medications, and minimal medication adverse effects), and minimal or no barriers to treatment access.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited as part of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cooperative Study number 430, Reducing the Efficacy-Effectiveness Gap in Bipolar Disorder, an 11-site randomized controlled trial that compared an easy-access treatment program and usual VA care (

15). Participants were enrolled from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2000. This study had minimal inclusion and exclusion criteria (for example, patients were not excluded on the basis of current co-occurring medical problems or substance use disorders) in order to represent as closely as possible the population of veterans with bipolar disorder seen in VA clinical practice. Participants were recruited as inpatients, were randomly assigned to treatment at discharge, and were then followed prospectively for three years. The study was approved by institutional review boards at all sites and at the VA study office.

Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type I or II by

DSM-IV criteria (

16); an index episode of manic, major depressive, or mixed episode by

DSM-IV criteria that required hospitalization on an acute psychiatric ward; and at least two hospitalizations on acute psychiatric wards more than three months apart over the previous five years. Exclusion criteria included moderate to severe dementia with a Mini-Mental State Examination score less than or equal to 26 (

17), unresolved substance intoxication or withdrawal, hospitalization on chronic or acute psychiatric wards for at least six months in the past year, and ongoing enrollment in mental health programs with a mobile outreach component in which clinical caregivers deliver services to the patient in the community.

Assessment battery

Intake assessment included informed consent as approved by each site's institutional review board followed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (

18) and a battery of interview and self-report instruments. This battery included a standardized summary of demographic and clinical characteristics, the Global Assessment Scale (GAS), the Somatotherapy Index and the Side Effects Summary (

15), the Patient Satisfaction Index (

19), self-reported health-related quality of life measurement that was assessed with the EuroQol (

20) and the 36-item Medical Outcome Study Short Form (SF-36) (

21), which has physical and mental health subscales.

The Somatotherapy Index was developed to gauge treatment intensity for the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study for the Psychobiology of Depression in the 1970s, and it has been updated and detailed to quantify current day treatments for bipolar disorder. The score on this index represents a summation of drug levels for all medications taken for bipolar disorder. Specifically, the index score is generated by categorizing drug concentrations for imipramine, lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine into five levels, with zero representing no drug taken and increasing levels representing increasing concentration. In addition, the number of alternative therapies that the patient was taking was also included and was categorized into the five groups, with 0 representing no alternative therapies taken; 1, one alternative therapy; 2, two alternative therapies; 3, three alternate therapies; and 4, four alternate therapies. Alternative therapies included gabapentin, clozapine, topiramate, tiagabine, a high dosage of thyroxine, calcium channel blockers, light therapy, and electroconvulsive therapy.

Existing survey items and relevant empirical and theoretical literature were reviewed to generate a pool of 29 items constituting barriers to care. Items included the general areas of barriers to obtaining care through the telephone, travel barriers, home commitments, lack of home support for care, difficulties gaining access to or receiving care at the clinical site, difficulty gaining access to timely appointments, pharmacy problems, and problems with communicating with providers (

22).

The Patient Satisfaction Index is a self-report instrument originally developed for use among primary care patients and was adapted for use among mental health clinic patients with varied educational and socioeconomic backgrounds (

19). The Patient Satisfaction Index contains 12 items that are rated on a scale that ranges from 1, agree strongly, to 6, strongly disagree.

The Working Alliance Inventory is a 36-item self-report instrument that evaluates patients' perception of the treatment relationship (treatment alliance) with their provider (

23). Items evaluate various domains within the treatment alliance, including perceived acceptance of and trust and confidence in the treating clinician. Providers here were the clinicians who were identified as an individual's primary mental health clinician, and patients were aware that the researchers would not share this information with their clinician. Clinicians also completed a similar assessment with respect to their patient.

Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) interrater reliability was good to excellent across the sites, including for the differentiation of bipolar from substance-induced symptoms, for bipolar diagnosis (Cramer's V=.98), for index episode polarity (Cramer's V=.83), for psychosis (Cramer's V=.65), for comorbid current and lifetime anxiety disorders (Cramer's V=.93 to .97 and .91 to .98, respectively), and for lifetime substance use disorders (Cramer's V=.94 and 1.00, respectively). On the Global Assessment Scale (GAS), the Shrout-Fleiss intraclass correlation coefficient was .86.

Treatment adherence was evaluated with interviews during the index hospitalization from the larger study while the participants were inpatients. Patients were queried about adherence to the prescribed medication regimen for the past 30 days. Patients were assured that their response to this query would be confidential and would not be shared with their clinician or nurse. A medication adherence score was derived from five possible patient responses: score of 1, never missed medication; 2, missed medication a couple of times but took at least 90 percent of prescribed dosages; 3, missed medication several times but took at least half of the prescribed dosages; 4, took less than half of the prescribed dosages; or 5, stopped taking all medication. Because of the possible impreciseness of self-report, we elected to compare the two extremes of self-reported adherence: individuals who self-reported full adherence to medication (score of 1) and those who self-reported substantial nonadherence to medication (medication adherence score of 4 or 5). These two groups of patients seemed to represent the most clinically relevant samples—patients with bipolar disorder who were adherent and those who were not. The literature suggests that patient-reported adherence is valid for identifying nonadherence in both medical and psychiatric populations (

3,

24,

25).

Statistical analysis

Patients who were adherent to medication and those who were substantially nonadherent were compared on patient characteristics (demographic variables; symptoms; health status; functional level; any current substance use disorder, which included both abuse and dependence; and psychosocial support). Also compared were features of the interaction between patients and providers (treatment alliance, medications, and medication adverse effects) and barriers to treatment. Two types of variables were involved in the comparative analyses: categorical and continuous. The comparisons that used categorical variables were accomplished with the chi square test, and comparisons involving continuous variables were performed with pooled t tests. All tests were two-sided. Because these were exploratory analyses no correction for multiple comparisons was made.

Discussion

This analysis suggests that individuals with bipolar disorder who are adherent to medication differ from those who are not on patient characteristics and patient-provider variables. Particular strengths of the analysis include the generalizability of the sample that resulted from the broad inclusion criteria and good representation of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups and older adults, populations that are frequently underrepresented in clinical studies.

This report was limited by the relatively small sample, underrepresentation of women in the sample, and the inclusion of only those individuals who agreed to participate in a research study. It must be noted that individuals in the nonadherent group do not represent the most extreme end of the nonadherence spectrum. At the most extreme end are individuals who decline to participate in research studies and those who decline to participate in treatment at all. However, despite these limitations, the results reported here are still useful in helping to identify individuals with bipolar disorder who are at the greatest risk of treatment nonadherence.

The analysis reported here exclusively used self-report to assess treatment adherence. No clear consensus exists on ideal methods of measuring treatment adherence for bipolar disorder (

1,

28,

29), and it is known that clinicians' assessment of treatment adherence may be remarkably poor (

3). Self-report measures of treatment adherence have a specificity of 90 percent, although they may overestimate actual adherence rates by about 15 percent (30). Many studies that include an assessment of adherence use self-report, often in conjunction with other measures, such as serum levels and chart reviews (14).

Scott and Pope (

3) have reported that when self-report ratings of medication adherence by patients with bipolar disorder are examined, the best measure of partial adherence is failure to take 30 percent or more of prescribed medication in the past month. This rating has demonstrated statistically significant associations with past nonadherence, repeated past nonadherence, any nonadherence in the past month, and nonadherence in the past week (χ

2=7.2, df=6, p=.03). Compared with nonadherence in the past two years, missing 30 percent or more of prescribed mood stabilizers in the past week has a specificity of 100 percent and a sensitivity of 65 percent. Compared with nonadherence in the past week, it has a specificity of 87 percent and a sensitivity of 84 percent (

3). In the study reported here, patients were informed that their statements regarding self-reported adherence would not be shared with treatment providers. One might expect that this assurance would encourage honest self-reporting and could possibly further increase the preciseness of self-report.

As anticipated with our original hypothesis, individuals with bipolar disorder who were nonadherent to medication were more likely to have current substance use disorders. Among individuals with any current substance use disorder (34 participants in the adherent group and 35 in the nonadherent group), alcohol was the most commonly abused substance. Subgroups for differing types of substances among individuals with any current substance use disorder were too small to analyze separately in a meaningful way. It is interesting that past substance use disorder does not appear to be associated with treatment nonadherence. Clearly, the immediate issues around current substance use (possible intoxication, poor judgment, and impulsivity) appear to be affecting treatment adherence the most. This finding makes a strong case for the need for easily accessible substance abuse treatment for individuals with bipolar disorder. Chemical dependence programs not only can minimize the negative medical sequelae of substance use but can also optimize the outcomes of bipolar disorder. The greater number of irregular hospital discharges among individuals in the nonadherent group were expected and might be thought of as existing on a continuum with nonadherence with all types of treatment.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, the two groups did not differ on symptoms, overall health status, functional level, or gender. It is possible that the small sample and the low number of women in the sample obscured real differences that have been reported by other investigators (

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13). A great majority of comparisons between the two adherence groups were negative in our analysis, which did not adjust for multiple comparisons. Although the possibility of type I error cannot be entirely ruled out, a majority of positive associations were as expected and supported by the literature. It is possible that there may be fewer differences among research participants, because they may be more likely than individuals in real-world settings to be motivated for treatment (and are largely treatment adherent). Interestingly, individuals who were nonadherent to medication were less likely than those who were adherent to receive disability benefits. It is possible that the processes that are associated with desire for treatment and self-help are the same ones that come in to play with the sometimes lengthy and complex procedures required to obtain disability benefits (recognition of a problem, desire to receive help, and perseverance). This aspect of treatment adherence has not been well studied and deserves further investigation.

In contrast to our original hypothesis, individuals who were adherent to medication had more prescriptions for different medications than those who were not adherent. Because no difference was found in symptoms between the two groups, this finding may be a reflection of intensity of treatment or may reflect the fact that providers may be more willing to prescribe medication to individuals who are more adherent to the medication regimen. Street and colleagues (

31) have suggested that building a partnership between patients and providers is reciprocal; thus a passive patient may become more involved when the provider offers encouragement, whereas a provider may become more active and engaged in response to a patient who asks questions and voices concerns. Although no difference was found between adherence groups on the treatment alliance scores, it must be noted that the assessment of treatment alliance did not clearly address all issues, such as stigma, that may be important in treatment acceptance and treatment adherence.

Although medication side effects have been cited as a major impediment to treatment adherence (

32,

33), this analysis showed that adverse medication effects did not differ between the two groups. The study design did not permit evaluation of dosing frequency for previous medications. However, it has been suggested that dosing frequency may be at least as important as the adverse effects of medication in predicting medication adherence for individuals with serious mental illness (

34).

Surprisingly, barriers to treatment did not differ greatly between the two groups. However, the study participants volunteered for the study, and it might be expected that individuals who experience the greatest number of barriers (and perhaps do not have access to participation in research studies) may differ from the population studied here. A recent report further describes perceived barriers to health care access in this clinical trial population (

35). It is likely that treatment nonadherence in this population with less access to care must be studied in naturalistic, nonresearch settings. Unique features of the VA health care system also may have affected study findings. With respect to potential cost barriers, pharmacy copay costs at the time of this study were negligible—$2 per prescription and free for many of the veterans. Findings could potentially differ in health systems in which out-of-pocket prescription costs are higher.

A recent report by this group of investigators noted that among individuals with bipolar disorder, treatment adherence may be identified as a self-managed responsibility within the larger context of a collaborative care model (

36). Adherence is likely to be enhanced within an ideal collaborative model in which individuals have specific responsibilities, such as coming to appointments and sharing information, and the provider likewise has specific responsibilities, such as keeping abreast of current state-of-the-art prescribing practices and being a good listener (

36). Although certain patient-centered factors, such as substance use disorders may be associated with treatment nonadherence, adherence is more than simply a "patient problem"—it appears to be, in fact, an important component of the provider-patient relationship. This finding underscores the importance of psychosocial treatment approaches that are interactive, flexible, and individualized.