Alcohol is the most common substance used by adolescents (

1), and alcohol use disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders among adolescents (

2). The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) estimated that 10 percent of adolescents aged 15 to 18 years met criteria for a lifetime alcohol use disorder (

3). Alcohol use disorders are highly associated with other psychiatric disorders (

4). Rohde and colleagues (

5) found that 82 percent of adolescents aged 14 to 18 years who had an alcohol use disorder also met criteria for at least one of several other psychiatric disorders.

Studies among adults have shown that a majority of persons with alcohol use disorders do not utilize substance abuse services (

6). Although the co-occurrence of alcohol use disorders with other psychiatric disorders is associated with an increased odds of service use (

6,

7), the prevalence of any use of mental health or substance abuse services among adults with comorbid alcohol and other psychiatric disorders is low (

6). Similarly, adolescents who participate in treatment for mental health problems have a high prevalence of substance use disorders; however, many of these substance use problems are not initially detected by clinicians (

8).

Current knowledge about the use of alcohol treatment services and the perceived need for alcohol treatment is based mainly on adult samples. Research among adolescents has typically failed to discriminate between their use of substance abuse services and their use of mental health services (

3,

7). Adolescents with substance use disorders are less likely than those with non-addiction-related psychiatric disorders to receive substance abuse care or mental health care (

7). Compared with adults, adolescents may face additional barriers to alcohol treatment. Many adolescents do not consider their substance use to be problematic (

9,

10). Even when adolescent substance users perceive a need for help, they may not be sure where or to whom to turn (

9,

11).

These studies suggest that adolescents who abuse or are dependent on alcohol are very likely to be underserved (

3,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11). Given that alcohol abuse and dependence are the most prevalent disorders among adolescents (

2) and that they tend to be co-occur with other psychiatric disorders (

4,

5), we examined the relationship between adolescents' use of mental health services and of alcohol abuse services. Specifically, we investigated the prevalence and correlates of the use of alcohol treatment services and of perceived need for such services among adolescents with alcohol use disorders who received mental health services and compared these youths with those who did not receive such services.

Results

Mental health service use

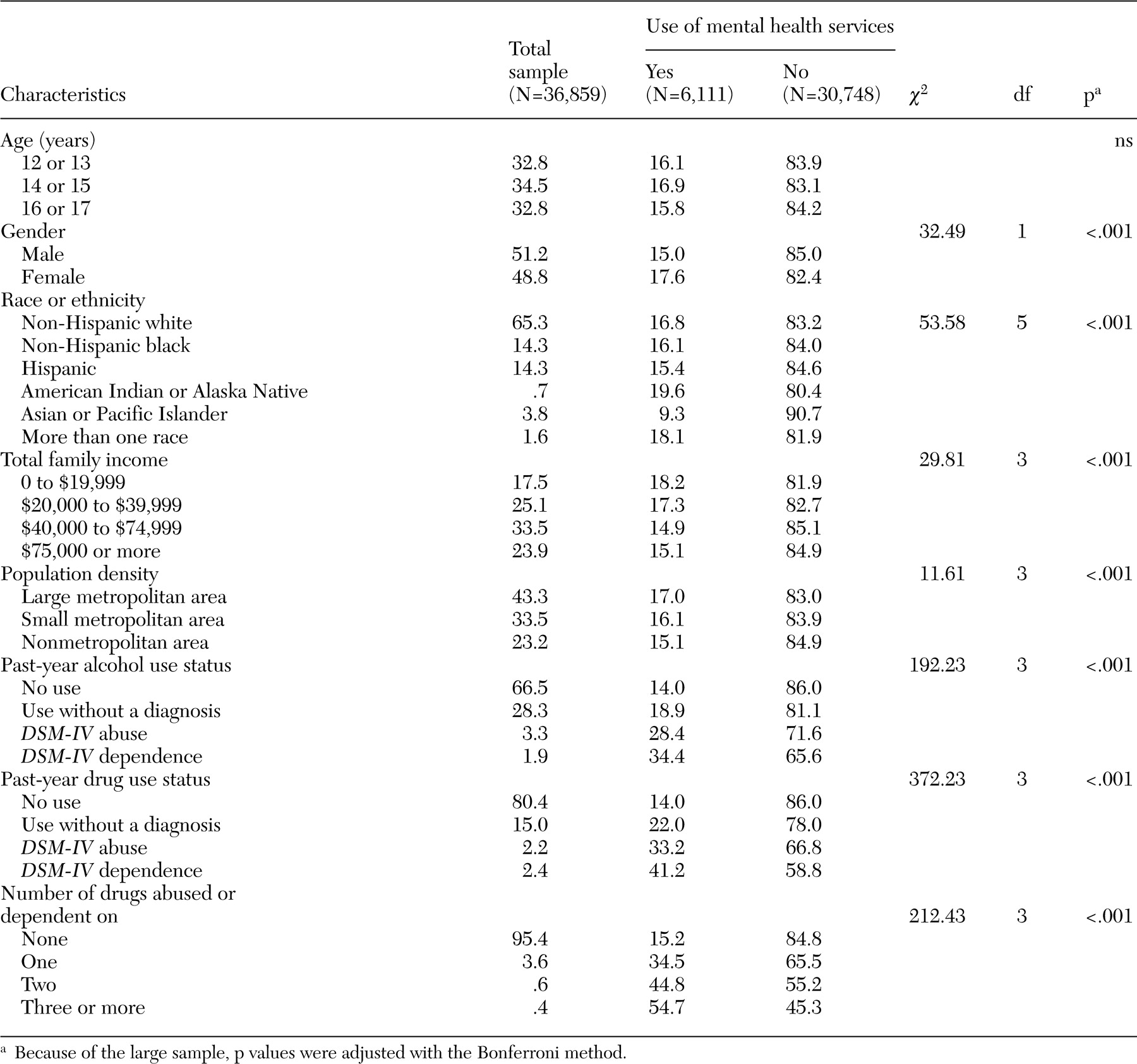

Among all adolescents aged 12 to 17 years in the two survey years (N=36,859), 16 percent (N=6,111) used mental health services for emotional or behavioral problems not related to substance use in the previous year. Of these mental health service users, 12 percent received inpatient mental health services and 61 percent received outpatient mental health services. The remaining users received mental health services at school. Reasons for receiving mental health services included depression (38 percent), acting out (17 percent), suicidal ideation or suicide attempt (14 percent), anxiety (11 percent), eating problems (6 percent), and other emotional or behavioral problems.

Table 1 shows that girls, American Indians and Alaska Natives, adolescents who reported more than one race, adolescents who reported the lowest level of family income, and adolescents who were living in large metropolitan areas were slightly more likely to receive mental health services than boys, Asians or Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, those reporting a higher level of income, and those residing in nonmetropolitan areas. Use of mental health services also was highly associated with alcohol and drug use disorders.

Alcohol use disorders

Adolescents who received mental health services were more likely than those who did not to meet the criteria for alcohol use disorders. Prevalence rates of alcohol use disorders among adolescents who used mental health services were 6 percent for abuse and 4 percent for dependence, respectively. The corresponding prevalence rates among those who did not use mental health services were 3 percent (χ2=57.51, df=1, p<.001) and 2 percent (χ2=57.01, df=1, p<.001), respectively. We then compared the co-occurrence of alcohol and drug use disorders. Users of mental health services were more likely than nonusers to meet criteria for both alcohol and drug use disorders. Of all adolescents with alcohol use disorders, 51 percent of mental health service users also had drug use disorders, compared with 33 percent of nonusers of mental health services (χ2=34.42, df=1, p<.001).

Alcohol service use

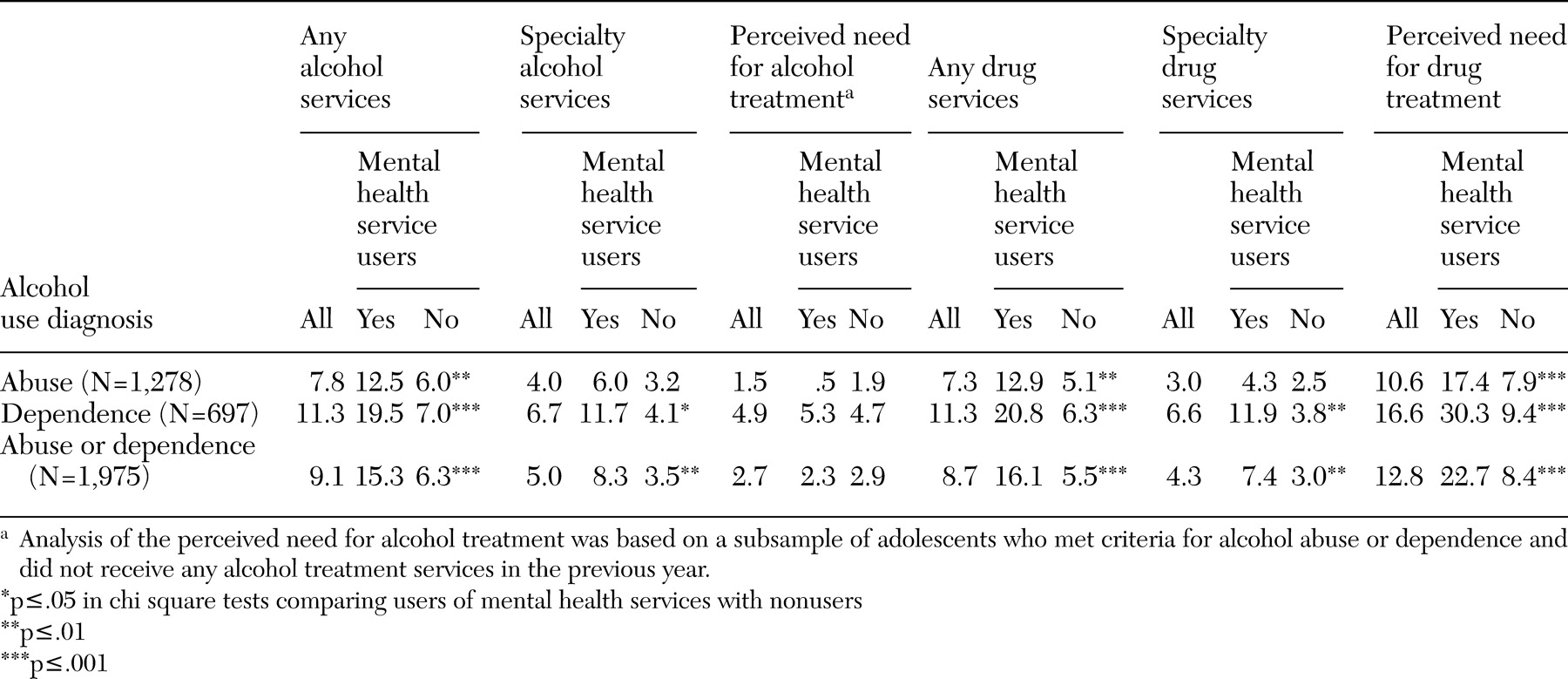

Past-year use of alcohol services by past-year use of mental health services is shown in

Table 2. Among alcohol abusers, mental health service users were more likely than nonusers to receive any alcohol service (13 percent compared with 6 percent) but did not differ from nonusers in their use of specialty alcohol treatment. Among adolescents with alcohol dependence, mental health service users were more likely than nonusers to receive any alcohol service (20 percent compared with 7 percent) and to receive specialty alcohol treatment (12 percent compared with 4 percent).

Because of the high prevalence of comorbid alcohol and drug use disorders among these adolescents, we also explored their use of drug abuse services. The prevalence of past-year use of drug abuse services was very similar to our estimate of alcohol services. Among adolescents with an alcohol use disorder, 9 percent used any drug abuse services and 4 percent used such services at a specialty setting. Overall, only 13 percent of adolescents with alcohol use disorders reported any service use for their alcohol or drug problems. Approximately 64 percent of service users received services for both alcohol and drug problems, and the remaining users received services for either alcohol problems (20 percent) or drug problems (17 percent).

Perceived need for alcohol treatment

Of the subsample of adolescents with alcohol use disorders who reported no use of any alcohol services in the previous year, very few reported needing alcohol services (

Table 2). Mental health service users were equally as unlikely as nonusers to report that they perceived any need for alcohol treatment (5 percent compared with 5 percent among those with alcohol dependence and 1 percent compared with 2 percent among those with alcohol abuse).

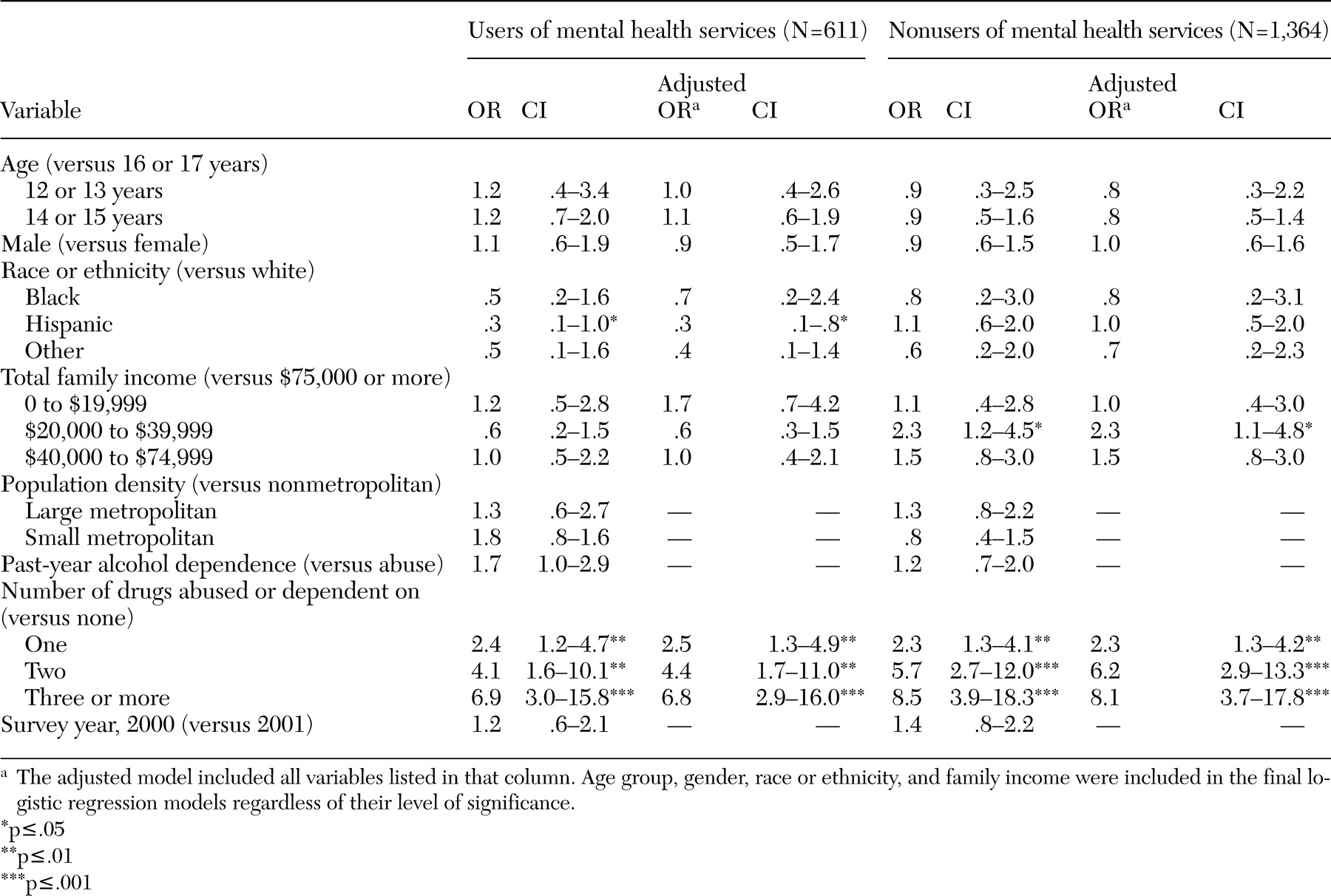

Logistic regression of any alcohol treatment services

The results of our logistic regression of any past-year use of alcohol services among adolescents with alcohol use disorders are shown in

Table 3. We found little variation in the characteristics that discriminated between the use of alcohol services by adolescents with alcohol use disorders who did and who did not use mental health services. Among those who used mental health services, Hispanic adolescents were less likely than whites to receive any alcohol service (adjusted OR=.3, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=.1 to .8).

Age group, gender, family income, population density, and alcohol use diagnosis (abuse versus dependence) were all unassociated with the receipt of any alcohol treatment service. Among nonusers of mental health services, family income was associated with the use of alcohol treatment services. Adolescents who reported a family income between $20,000 and $39,999 were slightly more likely than those who reported a family income of $75,000 or more to use any alcohol treatment services (adjusted OR=2.3, CI=1.1 to 4.8). Regardless of use of mental health services, having more than one drug use disorder was associated with an increased odds of using any alcohol service.

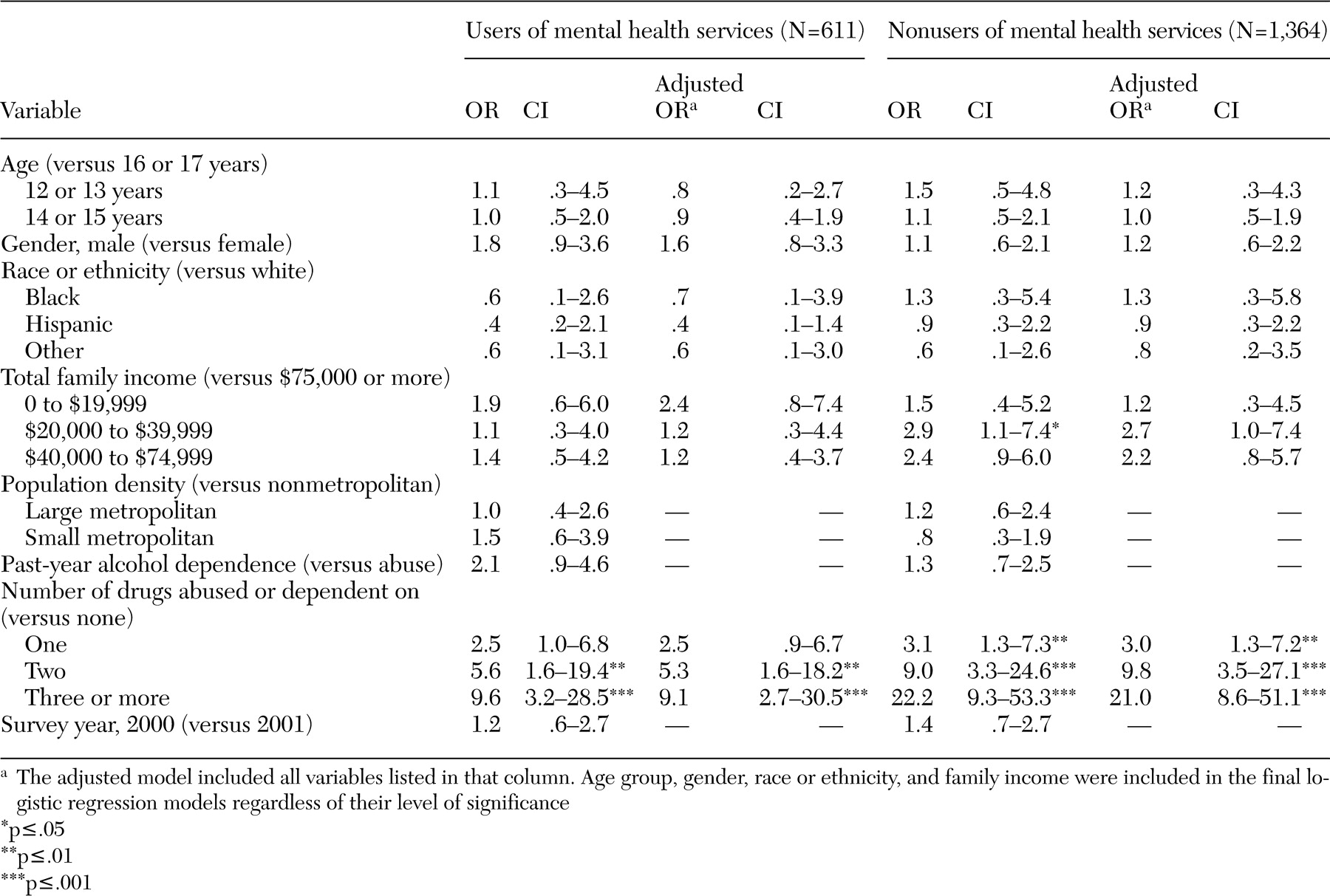

Logistic regression of specialty alcohol treatment services

We then determined whether the correlates of using specialty alcohol treatment among adolescents with alcohol use disorders differed by use of mental health services (

Table 4). Logistic regression indicated no significant differences in the use of specialty treatment by age group, gender, race or ethnicity, family income, population density, and alcohol use diagnosis. Regardless of mental health service use, the receipt of specialty alcohol treatment was highly associated with comorbid drug use disorders. Compared with adolescents without comorbid drug use disorders, adolescents who abused or were dependent on alcohol and had two comorbid drug use disorders were five times as likely to receive specialty alcohol treatment if they also used mental health services and were ten times as likely to receive such treatment if they did no use mental health services.

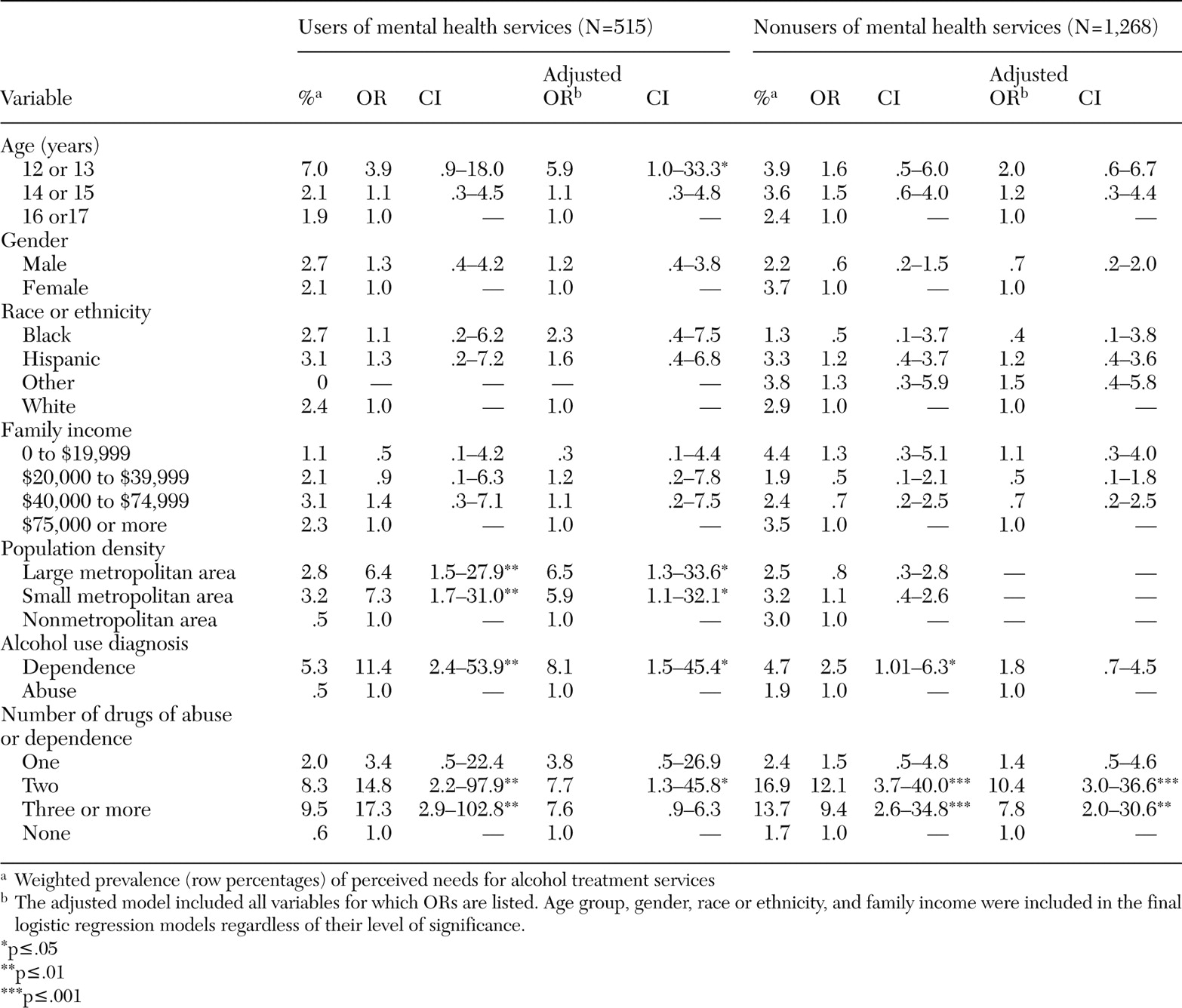

Logistic regression of perceived need for treatment

We then examined the perceived need for alcohol treatment among adolescents with alcohol use disorders who did not use any alcohol service in the previous year (

Table 5). We found that age group, population density, and severity of alcohol use were all associated with perceived need for alcohol treatment among mental health service users, but none of them was significant among nonusers of mental health services. Adolescents aged 12 or 13 years who had alcohol use disorders were six times as likely as older adolescents (aged 16 or 17 years) to report needing alcohol treatment. Adolescents who lived in metropolitan areas, compared with those in nonmetropolitan areas, and those who had alcohol dependence, compared with those who had alcohol abuse, were more likely to report needing alcohol treatment.

In contrast, the co-occurrence of multiple drug use disorders was strongly associated with the perceived need for alcohol treatment, regardless of use of mental health services. Compared with adolescents who did not have comorbid drug use disorders, those with two comorbid drug use disorders were eight times as likely to use alcohol treatment services if they also used mental health services and ten times as likely to report needing alcohol treatment.

Discussion and conclusions

We found that 5 percent of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years met criteria for past-year alcohol use disorders. The National Survey of Adolescents also reported that 4 percent of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years met criteria for past-year alcohol use disorders (

20). Consistent with the findings of other studies (

8,

21), we found that adolescents who received mental health services had a higher prevalence of substance use disorders than those who did not receive such services.

The most salient finding of this study is the very low prevalence of adolescents with alcohol use disorders who neither used alcohol services nor perceived a need for such services. Only 9 percent of adolescents with alcohol use disorders received any alcohol-related services, and only 5 percent received specialty alcohol services. Even when the use of drug abuse services was included, 13 percent of adolescents who abused or were dependent on alcohol received any alcohol or drug abuse services.

Of the adolescents who had alcohol use disorders and who did not receive any alcohol treatment service, only 2 percent of mental health service users and 3 percent of nonusers reported a need for alcohol treatment.

Our prevalence estimate of any use of alcohol services among adolescents who were dependent on alcohol (11 percent) is close to the estimate for adults who are dependent on alcohol (12 percent) (

16). The National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey also estimated that 10 percent of adults with alcohol use disorders received alcohol treatment services in the previous year (

22). Yet our prevalence estimate of perceived needs for alcohol treatment among adolescents who were dependent on alcohol (5 percent) is much lower than the estimate for adults (8 to 10 percent) (

16).

As with other studies (

9), we found that adolescents who received mental health services were more likely than those who did not to use any alcohol treatment services and to receive such services in a specialty setting. Kramer and colleagues (

8) found that, among adolescents who were seeking treatment for mental health problems, adolescents whose substance use problems were detected by clinicians at their initial assessments were much more likely than those whose substance use problems were undetected to receive specialty addiction care. Our findings and those of others highlight the importance of a thorough screening for comorbid substance abuse and mental health problems among adolescents seeking mental health services (

8,

9).

The low prevalence of use of alcohol treatment services appears to be related to the following factors. First, a majority of individuals with alcohol use disorders do not perceive the need for substance abuse services (

23). They typically do not consider their drinking to be a problem, or they prefer to handle it on their own (

10,

24,

25). There is generally a long lag time between the onset of an alcohol problem and contact with a health care provider (

26), and many individuals who abuse or are dependent on alcohol do not seek treatment until their alcohol use generates substantial problems in their lives (

27).

Second, adolescents with an alcohol use disorder may not be sure where to turn for help (

9,

11). Their access to and use of alcohol treatment services may depend in part on their parents' or other adults' recognition of alcohol problems and a need for treatment (

28). In this study, a majority of service users received treatment or counseling for both alcohol and drug problems, which is consistent with our findings that the presence of more than one drug use disorder is the primary determinant of use of alcohol treatment services and the perceived need for such services (

16,

29). It seems likely that the illicit nature of drug abuse behaviors brings adolescents to the attention of the criminal justice system, which in turn precipitates their entry into substance abuse services (

30). Adolescents with comorbid alcohol and drug use disorders also tend to run afoul of their schools, families, peers, and employers, which prompts others to identify them as needing help.

Third, adolescents with alcohol use disorders tend to have other psychiatric problems (

5). Parents and other caregivers may interpret the adolescents' alcohol use as a psychological problem and seek services that address that issue. Adolescents with substance abuse who also have mental health problems may use mental health services that are not designed specifically for addressing substance use problems (

9). Yet many adolescent substance abusers who are in mental health treatment are not identified early by clinicians as having substance use problems and do not receive appropriate substance abuse services (

8). Finally, stigma, cost of treatment, lack of knowledge about treatment programs and options, costs related to time and transportation, and negative attitudes toward alcohol treatment are other potential barriers to adolescents' use of alcohol treatment services (

24,

25,

31).

The results of our study suggest the need to educate the public about the symptoms of alcohol use disorders, their consequences, and the availability of treatment services (

16). For example, the use of media campaigns in educating the public about depression has generated significant positive changes in public attitudes toward depression and its treatment (

32). Among adolescents who have alcohol use disorders, the receipt of mental health services is not associated with their perceived needs for alcohol treatment, which suggests that adolescents may consider alcohol and mental health problems as two different conditions and that alcohol-related problems tend to be viewed as transient phenomena.

These findings should be interpreted with some caution. First, the NHSDA uses a cross-sectional design and relies on respondents' self-reports. Although we focused on alcohol use problems and service use that occurred within the 12 months before the interview, our findings could have been influenced by both memory errors and underreporting biases (

33). On the other hand, the NHSDA has incorporated computer-assisted interviewing techniques to improve the accuracy of self-reports of substance use behaviors (

34). Second, the lack of data on the quality of service obtained limited the breadth of our analyses. Third, our distinction between alcohol services and drug abuse services was based on adolescent self-reports, which may be influenced by adolescents' perceptions of their substance use behaviors and could be different from the view of service providers. Nevertheless, we found that about 84 percent of adolescents who abused or were dependent on alcohol and who received alcohol or drug treatment services reported the receipt of services for alcohol problems (64 percent for both alcohol and drug problems and 20 percent for alcohol problems only) and that 17 percent reported the receipt of services for drug problems only.

It appears that only adolescents with the most severe alcohol problems come to the attention of adults, who then facilitate their entry into treatment (

35). Overall, 91 percent of adolescents who had recent alcohol use disorders did not receive any alcohol services in the previous year and, of those who received no such services, 97 percent did not perceive the need for alcohol treatment. Underuse of alcohol services is widespread across all demographic groups. Hispanic youths and those without co-occurring drug use disorders may be less likely to be identified by others as having alcohol problems that require help. Untreated alcohol use disorders are highly costly to affected families and to society. More studies are recommended to specify the factors that impede the identification of alcohol problems and access to alcohol services.