The aim of our study was to explore the levels of life satisfaction among patients in Finland with schizophrenia who were discharged from hospitals into the community and the factors associated with their satisfaction. Data were obtained from the Discharged Schizophrenic Patients project, a national project.

Results

Sample

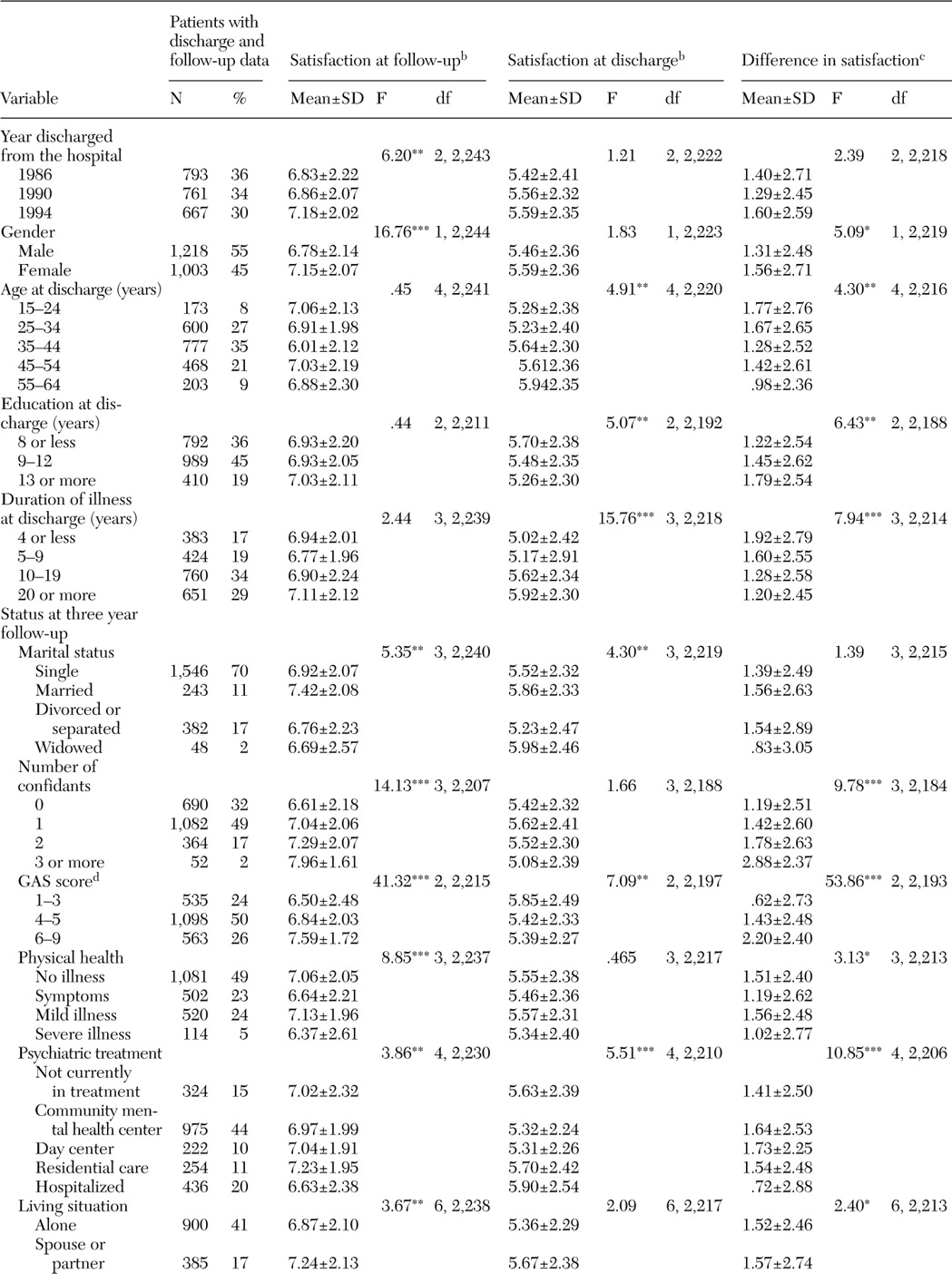

Satisfaction at both time points was adequately measured for 2,221 of the 2,232 patients who were interviewed (99.5 percent). The sociodemographic background characteristics and clinical history of these patients are shown in

Table 1. These data represent the independent variables. In terms of sociodemographic background factors, no statistically significant differences were found between the patients who were interviewed at the three-year follow-up and those who were not. However, at the time of discharge, the global psycho-functional ability (as measured by GAS) was poorer among the patients who were interviewed at the follow-up, compared with those who were not. Also, patients who were interviewed at the three-year follow-up used psychiatric services to a greater extent both before and after discharge.

In this study, the two measures of satisfaction—SAD (mean±SD score of 5.52±2.36) and SAF (mean score of 6.95±2.12)—and the difference between these two measures—SDI (mean score of 1.43±2.59)—were used as dependent variables. By using the score closest to the means, patients were divided into two groups: nonsatisfied (SAD score of 0 to 5 [1,089 patients, or 48.9 percent] or a SAF score of 0 to 7 [1,233 patients, or 54.9 percent]) and satisfied (SAD score of 6 to 10 [1,136 patients, or 51.1 percent] or a SAF score of 8 to 10 [1,013 patients, or 45.1 percent]). Additionally, patients were divided according to whether they had experienced a decrease or an increase in satisfaction over the study period (SDI score of -10 to -1 [353 patients, or 15.9 percent] or an SDI score of 1 to 10 [1,365 patients, or 61.5 percent]. The remaining 503 patients (22.6 percent) had experienced no change (SDI score of 0), and they were excluded from logistic regression analyses in which SDI was a dependent variable.

Bivariate analyses

SAD, SAF, and SDI scores, according to the patients' sociodemographic and clinical background, are shown in

Table 1. Patients discharged in 1994 were more satisfied than those discharged earlier. Women had higher SAF and SDI scores than men. Age was associated with SAD and SDI scores but not with SAF scores. Compared with older patients, younger patients reported less satisfaction at discharge and had thus experienced more positive changes. Marital status at the three-year follow-up was associated with both SAF and SAD scores. Married patients reported high satisfaction both at discharge and at follow-up, and widowed patients reported high satisfaction at discharge. Patients with a higher level of education had lower SAD scores and higher SDI scores—that is, they had experienced more positive changes than those with less education.

Patients with a shorter duration of illness reported more positive changes, compared with those with a longer duration. Diagnostic subgrouping (not shown in the table) was not associated with satisfaction scores. As expected, GAS scores at follow-up were associated with SAF, SAD, and SDI scores. Patients with lower GAS scores expressed lower satisfaction at follow-up, remembered their satisfaction at discharge as being relatively higher, and had experienced fewer positive changes than patients with higher GAS scores. The corresponding correlations with SAF, SAD, and SDI scores were r=.213 (p<.001), r=-.072 (p=.001) and r=.244 (p<.001), respectively. As can be seen, the correlation between GAS and SAD scores was very low.

SAF scores were negatively correlated with psychotic (r=-.142, p<.001), neurotic (r=-.197, p<.001), and depressive symptoms (r=-.273, p<.001), whereas SAD scores were negatively but very weakly correlated with neurotic (r=-.089, p<.001) and depressive symptoms (r=-.097, p<.001). SDI scores were correlated negatively with psychotic (r=-.115, p<.001), neurotic (r=-.084, p<.001), and depressive symptoms (r=-.137, p<.001).

Patients with severe physical illness had lower SAF and SDI scores. Interestingly, patients with physical symptoms but without any diagnosed physical illness also had low SAF and SDI scores. Patients hospitalized at follow-up had higher SAD scores but lower SAF and SDI scores. This finding indicates that currently hospitalized patients remembered their life situation at the time of discharge as being relatively good, but at the time of examination they were dissatisfied and had experienced more negative changes during the follow-up period.

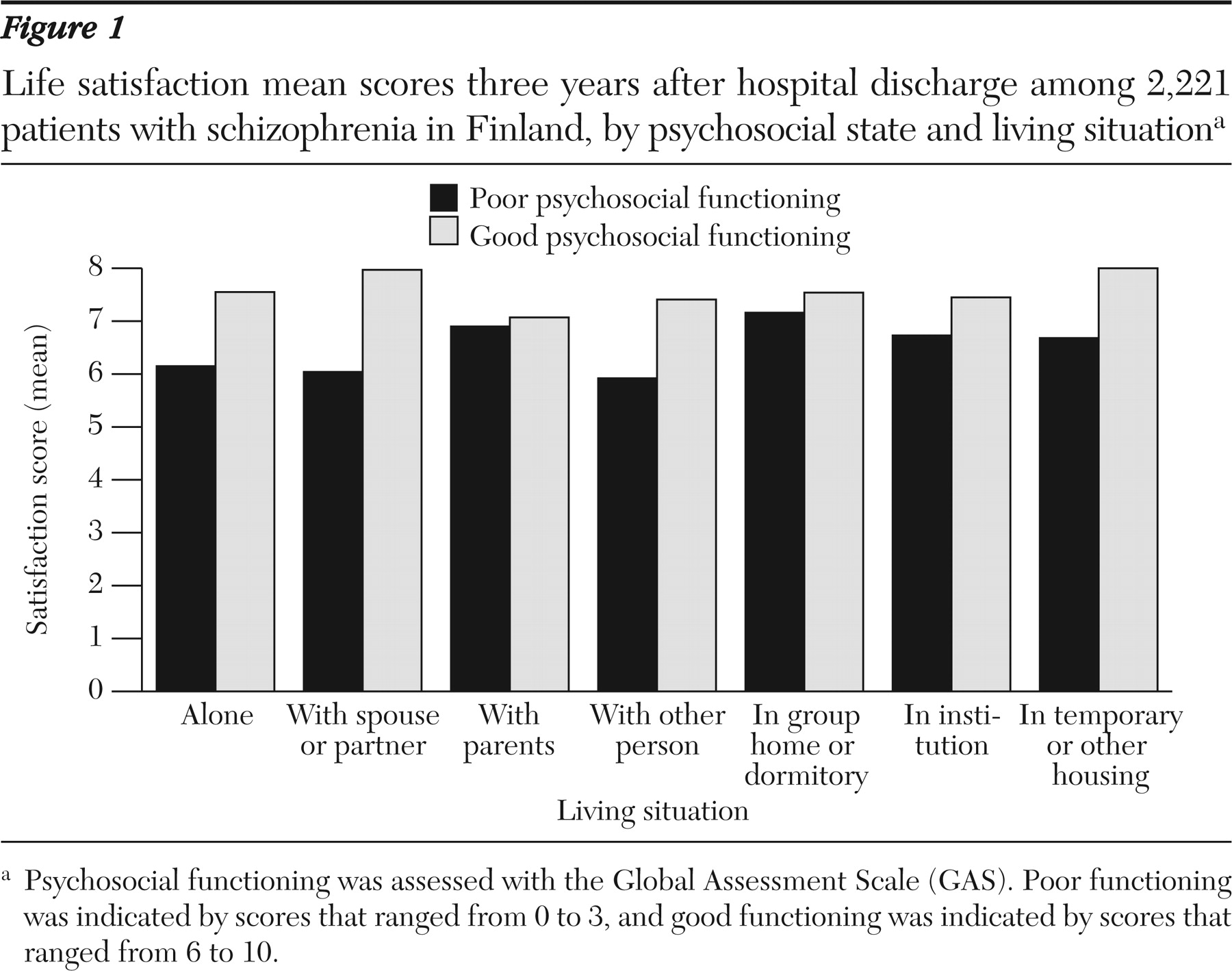

Living situation at follow-up was associated with SAF and SDI scores but not with SAD scores. Patients who lived with their spouse, in group homes or dormitories, or in another or a temporary housing arrangement were more satisfied than patients who lived alone, with their parents, with another person, or in an institution. GAS scores interacted with housing situation (F=2.16, df=12, 2,197, p=.011). Thus SAF scores were calculated for patients with low GAS scores (score of 0 to 3) and for those with high GAS scores (score of 6 to 10), according to living situation (

Figure 1). Patients with low psychosocial functioning had relatively high satisfaction if they lived with their parents, in group homes or dormitories, or in institutions (F=2.26, df=6, 540, p=.037), whereas patients with good psychosocial functioning were less satisfied if they lived with their parents (F=2.77, df=6, 557, p=.012).

Multivariate analyses

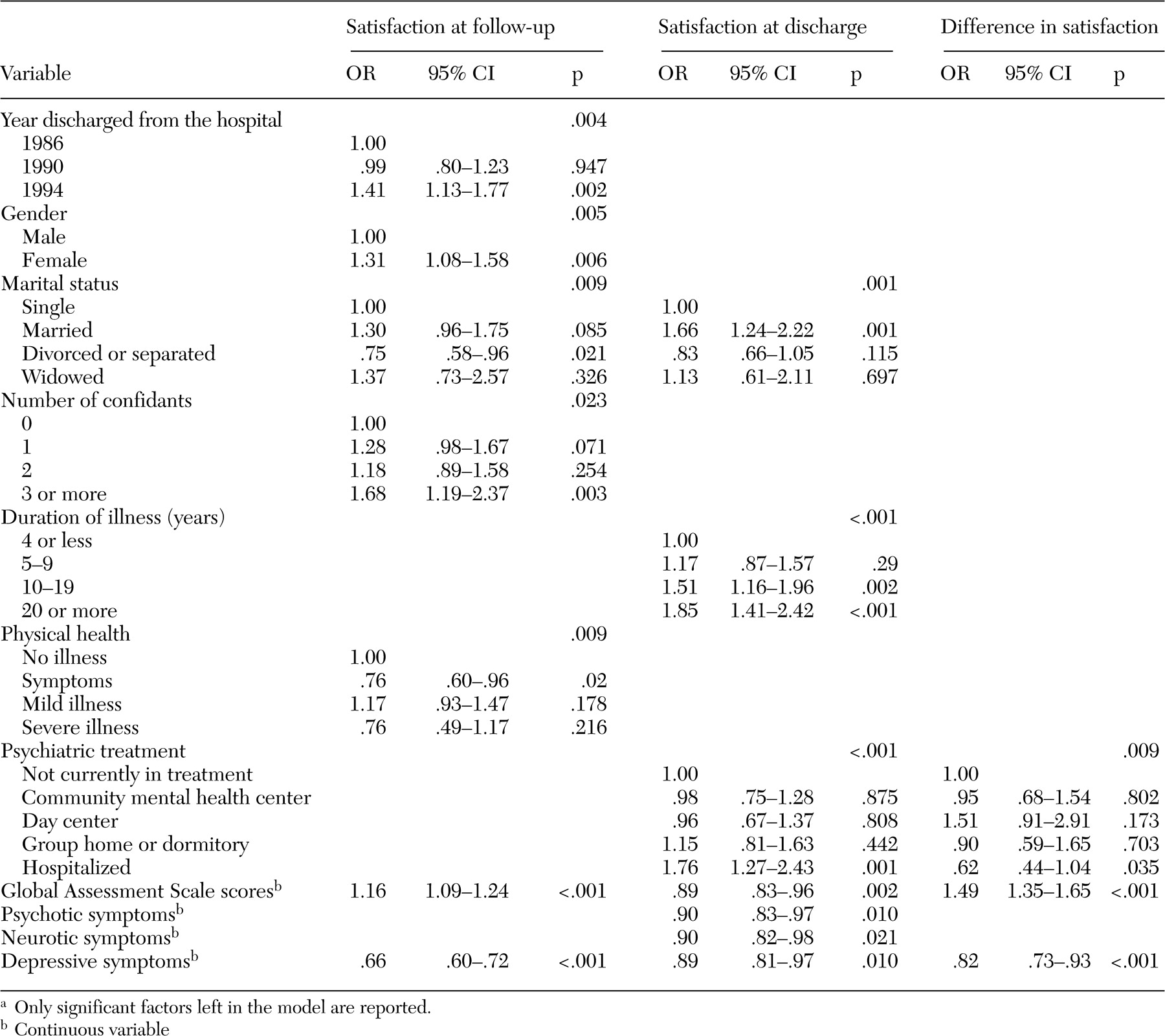

Results of logistic regression analyses are shown in

Table 2. Discharge year, gender, marital status, number of confidants, and physical health as well as GAS scores and depressive symptoms were statistically significant predictors of SAF scores. Women and patients with several confidants, with good psychosocial functioning (GAS), and without depressive symptoms expressed high satisfaction, whereas divorced or separated patients and those with several physical symptoms were dissatisfied.

When GAS scores and symptoms of mental illness were omitted from the analysis, the other explanatory variables shown in

Table 1 remained in the model. When discharge year was also omitted from the analysis, living situation entered into the model. This finding was analyzed more closely in the ANOVA in which SAF scores were explained by discharge year and living situation. This analysis showed that the effect of living situation remained significant (F=3.07, df=6, 2,224, p=.005), whereas the effect of discharge year was no longer significant. Thus categorization of SAF scores meant that living situation lost its effect at the expense of discharge year.

SAD scores were explained by marital status, duration of illness, and treatment situation. Compared with their reference groups, married patients, patients with a long duration of illness, and currently hospitalized patients scored their satisfaction at discharge as being higher. Interestingly, patients with poor psychosocial functioning (as measured by GAS scores) and few symptoms of mental illness (psychotic, neurotic, and depressive) had high satisfaction scores at discharge. When GAS scores and symptoms were omitted from the analysis, the other explanatory variables shown in

Table 1 remained in the model.

SDI scores were significantly explained only by treatment situation, GAS scores, and depressive symptoms. Compared with the reference groups, currently hospitalized patients, patients with poor psychosocial functioning, and those with more depressive symptoms had experienced more negative changes in satisfaction. When GAS scores and depressive symptoms were omitted from the analysis, in addition to treatment situation, being hospitalized (odds ratio [OR]=.40, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=.27 to .62, p<.001), the number of confidants (three or more, OR=1.67, CI=1.05 to 2.65, p=.030) and physical health (having symptoms, OR=.72, CI=.54 to .97, p=.031) also entered into the model.

Discussion

The sample consisted of patients with schizophrenia as defined by

DSM-III-R who were discharged from psychiatric hospitals in Finland at baseline. The patients had been ill for an average of about 15 years, and about 90 percent of them were receiving disability payments because of their illness at follow-up (

16,

17). Compared with patients who were not interviewed at the three-year follow-up, those who were interviewed had been more disturbed at discharge and had used psychiatric services more often both before and, in particular, after discharge. These findings indicate that the sample represents severely disabled patients and that the results of this study can be generalized to patients with long-term schizophrenia. The large study sample reported on here represents patients with schizophrenia who were discharged from hospitals throughout Finland, and thus the sample gives a more general view of patients' satisfaction than local samples.

The major findings of this study were that gender, number of confidants, symptoms of mental illness, and psychosocial functioning were the major determinants of subjective life satisfaction among patients with schizophrenia. Global assessments of psychotic, neurotic, and depressive symptoms represent the level of psychopathology and GAS scores represent the level of functioning, although the GAS also assesses symptoms of mental illness. Many other studies have shown that the psychopathology of patients correlates with life satisfaction (

2,

3,

8,

18). On the other hand, the good psychosocial outcomes of female patients with schizophrenia (

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24) could explain why female patients in our study were more satisfied than male patients. However, our study showed that symptoms of mental illness and current psychosocial level of functioning do not explain gender differences in life satisfaction; independently of these assessments, women were more satisfied with their life than men.

In addition to gender, the number of close friends or confidants was strongly associated with greater life satisfaction, even when the effects of symptoms of mental illness and psychosocial status were controlled for. This finding has also been shown in other studies (

25). This finding demonstrates that patients who were able to create and maintain close interpersonal relationships were the most satisfied with their lives. Close interpersonal relationships thus seem to act as a gender-independent factor in life satisfaction. Roder-Wanner and colleagues (

26) found that, although the women in their study did not have more social contacts than men, the number of contacts with friends explained satisfaction with life in both genders.

It is interesting that no significant associations were found between age or duration of illness and life satisfaction at follow-up. Instead, younger patients who had usually been ill for a short time reported low satisfaction at the time of discharge and had, therefore, experienced more positive changes than older patients who had experienced a long duration of illness. This finding may mean that (younger) patients with a short duration of illness actually experienced hospitalization as being worse, compared with older patients who had already had more frequent and longer hospitalizations. It is possible that, compared with older patients, younger patients' expectations regarding their life were higher; therefore, hospitalization was experienced by them as being more unsatisfactory. Older patients were used to their chronic illness, and their expectations were presumably lower.

Compared with patients with less education, the better-educated patients who were younger and had a shorter history of illness reported less satisfaction at the time of discharge, but when the analyses controlled for duration of illness, this association was no longer significant. Thus education seems not to be independently associated with satisfaction. Also, it is plausible that better-educated patients had higher expectations of their life; therefore, hospitalization had a more damaging effect on their levels of satisfaction.

In the study reported here, not only the mental state and psychosocial functioning but also the physical state was an important factor associated with life satisfaction. Physical illnesses are prevalent among patients with schizophrenia (

27,

28) and can thus decrease patients' life satisfaction. In addition, the occurrence of physical symptoms without a diagnosed illness was associated with low satisfaction, which may be a reflection of the uncertainty that such symptoms produce. Hansson and colleagues (

25) also found that satisfaction with health was the major factor associated with subjective quality of life. Careful physical examination and treatment of the physical illnesses of patients with schizophrenia are also important from the point of view of patients' life satisfaction.

Patients who were living in the community were more satisfied than hospitalized patients, and this finding was not explained by other factors, such as gender, mental state, or psychosocial functioning. Compared with patients who were living in the community, currently hospitalized patients remembered their life situation at discharge as exceptionally good, emphasizing their willingness to leave the hospital. Interestingly, patients who were living in group homes or dormitories were the most satisfied.

When the life satisfaction variable was categorized in the multivariate analysis, the association between current life satisfaction and living situation disappeared, whereas an association between life satisfaction, and discharge year appeared. However, in the ANOVA, living situation had a significant effect on current life satisfaction but discharge year did not. This discrepancy is explained by the fact that after 1990 the number of patients living with their parents (low satisfaction) decreased and the number of those living in group homes and dormitories (high satisfaction) increased (

16). We believe that the effect of discharge year on current life satisfaction was caused mostly by changes in patients' psychosocial situation. Together, these findings indicate that rather severely disabled patients with schizophrenia prefer living outside of hospitals in accommodations that offer more support than, for example, visiting outpatient clinics or day centers.

The association between life satisfaction and living situation seems to be dependent on the patient's psychosocial functioning. Patients who have poor psychosocial functioning need more daily support, and those who were living with their parents, in group homes or dormitories, or in a hospital expressed relatively high satisfaction. It is likely that their original home, their own parents, staffed group homes or dormitories, and even hospitals can offer the support and security that patients miss when their own mental state and functioning are very limited. However, this type of living situation also means that the burden or stress on the patient's family members is high; therefore, they need support from the psychiatric care system (

29).

Among patients with good functioning the situation was different. Among this group, those who lived with their spouse were the most satisfied, whereas those who lived with their parents were the least satisfied. Dependence on parents may be one reason for these patients' dissatisfaction, which could be reversed if they had the option of living more independently or were given support to live that way. Providing such a living situation is a challenge for the local community. It is worth noting that even currently hospitalized patients with good functioning expressed higher satisfaction than those who were living with their parents. In these cases, hospitalization may be temporary and patients will return to the community. Finally, living in group homes or dormitories had an independent positive effect on life satisfaction. Among patients with long-term schizophrenia, this kind of living arrangement seems to be relatively satisfactory, especially if patients do not have a spouse or a partner.

This sample of patients was extensive, and the response rate was good. The study sample represents adequately the population of patients discharged from mental hospitals in the whole country, so the results can be generalized to the whole population of patients in Finland with long-term schizophrenia. However, this study has limitations related to the study design and data collection. Because of the retrospective study design, conclusions about changes in life satisfaction should be drawn with caution. The question "How satisfied were you with your life situation at the time you were discharged from hospital three years ago?" asked for the patient's recall of the situation three years earlier. However, discharge from the hospital acted as an anchor point, which possibly made it easier to recollect the actual feelings of satisfaction. Although assessment of satisfaction at the time of discharge should be seen in the light of the study methods, the assessments give us important information about changes in life satisfaction and the patients' perspective on their life.

We used only one scale for measuring life satisfaction, and various dimensions of life satisfaction may not have been covered. The visual analogue scale is a simple technique for measuring subjective phenomena, and it has been shown to be reliable and valid in most circumstances (

30,

31). Accordingly, it proved to be easy for the patients in our sample to understand. As an indicator of mental state, we used global assessment of psychotic, neurotic, and depressive symptoms and the GAS, which, in addition to psychosocial functioning, includes a global assessment of psychopathology. A more detailed and standardized description of patients' symptoms would have permitted closer study of the associations between psychopathology and life satisfaction in schizophrenia. However, we believe that global assessment of major symptom groups and GAS scores substantially controlled the effect of symptoms on satisfaction.