Moments of High Receptiveness and “Now Moments”

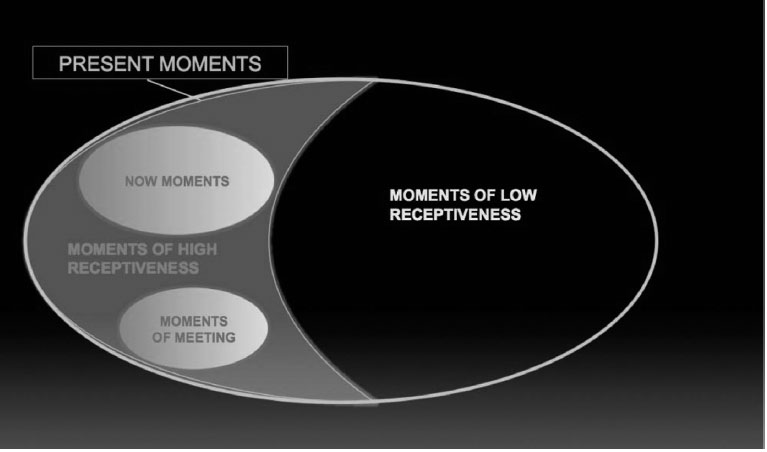

As represented by

Figure 1, all

now moments are

MoHR, but not the reverse, as

MoHR encompass a broader category. Given the inclusive nature of

MoHR with respect to Stern’s

now moments, it is natural that they should share their characteristics.

To demonstrate the difference between these concepts, and especially their repercussions for technique, we will take a published clinical example of a now moment and a moment of meeting between patient and therapist (

Altman, 2002). Altman writes the following clinical vignette from one of his patients, Mr. P, which happened after two years of working together (p. 509):

… he came into my office one day, greeted me, and fell into a silence. It was not unusual for us to sit in silence like this. I had learned that it was usually futile for me to intervene in a silence, to ask questions or make observations. Mr. P would respond to what I said, but perfunctorily. The really meaningful and emotion-laden interchanges nearly always were initiated by Mr. P himself, so I had learned to wait.

As I sat there, I became aware of the sound of a piano coming from outside my window, playing a beautiful, mournful, poignant melody. It seemed like background music for our session; I waited for something sad to happen. Mr. P spoke: he had been listening to the new album of Emmy Lou Harris (a country music singer), and one of the songs had so touched him that he had spent an hour the previous day, alone at home, sobbing and thinking about his father. He described how beautiful the music was, how the lyrics of the song evoked the singer’s sad reflections on a man who had been fatally wounded emotionally long ago.

As it happens, I am also a fan of Emmy Lou Harris, had recently been to one of her concerts, and had been planning to go out and buy this album as soon as possible. I had not yet heard the song my patient was describing, but right after my premonition associated with the sad piano music (which meanwhile had disappeared or faded into the background), I was stunned to find that we had a shared responsiveness to this particular singer, this emotional territory from our outside lives.

I listened intently to what my patient was telling me about the song that so moved him, adding some of my own associations to the lyrics. Toward the end of the session I told Mr. P, with amazement, about my response to the piano music (he said he had not heard it), and how I shared his love for Emmy Lou Harris. He wondered if I had yet heard the song, and I told him no, but I would by our next session.

Mr. P, up to this session, was not aware of having any feelings about his father at all. His father was so emotionally distant, if not dead, that Mr. P felt his physical death would be nearly superfluous*

Later on Altman adds, “So Mr. P’s being overcome with feeling for his father was a major breakthrough (p. 510).”

Taking into account the limitations of being an outside reader, in our opinion there was a previous MoHR, which occurred in the home of the patient as he was listening to the song by Emmy Lou Harris. It may well have been this moment in which a new thematic area was opened and, above all, that gave it a measure of connection/affective charge.

Although this was picked up in the session, and this theme possibly reopened/reactivated by Altman’s self-revelation (thus creating a new MoHR), we would like to contemplate what it would have been like if Altman and Mr. P. had relived the experience together by listening to the song during the actual session itself.

According to the theory of memory reconsolidation, listening to the song together in session would reactivate the mnestic elements with a high-affective charge connected with Mr. P’s father that emerged when he listened to the song alone. At exactly that moment of high receptiveness the mnestic elements would move into a labile state. In this state, these mnestic elements would be susceptible to coupling with another different experience in order to be modified. This experience could take the form of an emotional response from Altman, lead to interpretative elements on these affects, or elicit a combination of both, etc.

The definitions of now moments/moments of meeting (of which Altman was aware) must in some way direct his point of view and orient his technique. We recognize the validity of both the focus and the technique and there are occasions when this may be the best way to take advantage of spontaneous moments produced by the therapeutic bond.

However, the concept of

MoHR, which encompasses both now moments and moments of meeting (see

Figure 1), offers differential elements, which give it intrinsic value. Firstly,

MoHR has its origin in a theoretical concept based on neurobiology which has been endorsed on an experimental level (

experiential coupling). Secondly, because it gives us the possibility of directly employing some of the given stimuli, it offers the therapist additional technical elements, which favor therapeutic change. Lastly, it provides new foundations for applying active technique to psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Moments of High Receptiveness and “Moments of Meeting”

As we have already pointed out, MoHR is a concept that encompasses moments of meeting. These ideas share characteristics, but the former (unlike the latter) can be derived from elements outside the therapeutic bond or link. Later in the article we will look into this in more depth, when we propose some ways of inducing, recognizing, and making the most of MoHR.

We will endeavor to demonstrate the comprehensive character of

MoHR with an example. In order to do so, we present an ideal timing sequence in a model described by Stern (

Stern et al., 1998):

1.

the spontaneous appearance of a now moment in the intersubjective space between therapist and patient.

2.

resolution by way of a specific intervention, with the therapist’s signature, in the now moment which gives rise to a moment of meeting.

Both of these moments would be MoHR.

Now let us imagine that this same sequence starts with the now moment but, rather than being followed by a response from the therapist (with all the characteristics pointed out by Stern for a moment of meeting), it is instead followed by an intervention that lacks these characteristics.

In this scenario, the difference is immediately obvious. In Stern’s theoretical model, the present moment produced would not be a now moment (it is not spontaneous, it is derived from the effects of an intervention by the therapist), neither would it be a moment of meeting.

In the model we propose, the present moment created would be a MoHR (although the elements activated may be different from those mobilized by the preceding now moment). A failed intervention, as we will see later on in triggering stimuli, also produces a MoHR, which, if it is taken advantage of, possesses great therapeutic potential.

Moments of High and Low Receptiveness

We will now examine some clinical vignettes in which the difference between moments of low and high receptiveness to intervention can be perceived.

Let us now consider the case of C, a 46-year-old woman in treatment for multiple phobias. The clinical presentation was of an intense emotional paralysis, which, at certain moments, would become a cognitive paralysis (mental block) when faced with masculine figures of authority. The patient had previously been in treatment. During that treatment she discovered some aspects of her childhood that related to a degrading father and older brothers who transferred the aggression and rejection suffered at the hand of their father to their younger siblings, C among them. We verified this recollection by the substantial evidence that emerged in treatment. However, this knowledge did nothing to stop C from experiencing the same emotional paralysis and even cognitive/mental block.

C needed to relive these sensations experientially in session (which would create a MoHR), and she also needed proposals for actions she could take in real life (

Power, 2000) that would give her sufficient ego resources to make change possible. By reliving both the experiences of her childhood that caused the block and her new, real-life experiences, the information she already possessed about her childhood permeate her structure and act as preparatory step for further new experiences.

This was a complex process with regard to the number of intervening elements that produce change (exposure, learning ego resources, the comprehension of feelings and emotional states, etc.). What was previously known has a limited effect because it was suggested in a moment of low receptiveness, during which bringing the unconscious into the conscious did not overcome the symptoms. Only when interpretation joined forces with experiential coupling its effect was possible, and in this case, it was only in the MoHR that the interpretation became effective.

It could be argued that previous interpretations had not been made on the same terms, and that their motivational valences were not strong enough to produce change. The technical modifications brought into this treatment were the result of having read Bleichmar’s work (2001). While it is likely that the interventions during the first year of treatment were not exactly the same in terms of motivational valence, it is difficult to attribute the change to these differences or any other single element. We questioned this mechanism because the change experienced by the patient was not only behavioral, but also because of the symbolic and procedural modification of the codes through which she related to herself and reality. Bleichmar calls this “passionate belief matrixes” (

creencias matrices pasionales, revised by

Méndez and Ingelmo, 2011).

2Continuing with the description of the evolution of the clinical case, C successfully adapted to a new work environment, with a new boss and workmates. She also separated from her partner and explored other possible romantic relationships, including blind dates through a social networking service. As evidenced both by her romantic separation and in subsequent relationships, she experienced a sense of value in herself and of having something valuable to offer others. This has allowed C to approach romantic relationships with men differently; her attention was not focused solely on the possibility of rejection as it had been in the past. This anxiety, which had been dominant most of the time, usually led to an almost automatic sense of paralysis. After our work, C was able to see herself as someone worthy of attention, and she was able to act on whether to accept or reject the offer of a relationship.

M, a woman of 52, had a borderline personality disorder in which dissociation constituted a noticeably prevalent mechanism. In one session we were going through some photos from her adolescence, and she found one in which she has long black hair. It brought on the following association: “I look at this photo and I remember the feeling of brushing my long hair, how I felt when I left the house to go out. It was a bone of contention between my mother and I, who thought it unrefined (here M. clarified that her mother believed hair should either be worn short or tied back). P, my boyfriend at that time, loved my hair but my mother said it was gypsy like. I responded by saying that P loved gypsies and thought them the most beautiful women in the world.” The contemplation of the photo vividly evoked the memory of brushing her hair in her youth that created the MoHR.

At that moment, M brought up an instance in which she cut off her hair

3 as a self-aggressive behavior in response to feeling rejected by her husband; it added a link to previous interpretations regarding her reaction to abandonment, “I leave them before they can leave me,” and the cutting of her hair, “When I see my hair going gray, how it has lost the vitality it had before, it doesn’t feel like my own hair anymore.” The photo brought up, in connection with an affectively charged memory, both the feeling of narcissistic possession that M’s long hair represented and the feeling of loss with the passing of the years. This in turned opened the possibility of dealing with age and the fear of deterioration, a fear which was multiplied because M’s mother had Alzheimer’s disease. None of the previous work done with M—encouragement of self-observation, provision of framework in which to view herself—would have had the same effect on her had she not experienced that state of high receptiveness triggered by the photograph and the memory it provoked

4.

It is worth noting that the mnestic-semantic component alone does not constitute a MoHR. The experiential component is paramount, and not only because it is the motor that sets in motion the MoHR, but also because it is indispensable that patients feel themselves to be the subject of the action. The high motivational valence of the memory of that experience, due to the quality of the emotion, resolves the patient’s defenses against this memory. We could say that one cannot deny what one is feeling at that very moment while observed by another. To illustrate what we have just said, consider the emotional experience involved in carrying out an ultrasound on a pregnant woman. The experience of being pregnant is undeniable for both; it is “beyond all doubt.” So, what is central from that experiential moment on is how to deal with this experience, how to go ahead or interrupt the process, how to begin the additional care of the fetus or the mother, etc.

Let us now consider an additional clinical vignette of the M case. Her account of motherhood lacked an associated emotional component; it was purely semantic, told in a flat tone of voice when she recalled both good and bad events, but particularly on the bad events. One day in session, M made reference to a book she was reading: “… there is scene that has something to do with me but I don’t know what it is.”

I asked her to read aloud that part of the text that affected her. In the story, a mother and her 10-year-old son take a trip to a lake. While the son splashes about in the water, the mother experiences a panic attack described as enveloping black waves and earth trembling beneath her feet. In a daze, she can hear screams for help from her son but cannot respond to them until a hiker intervenes, and though he tries to save the boy, it is too late, the child dies. The hiker asks the mother “Why didn’t you scream?” Later in the novel, the woman experiences headaches, nightmares of being trapped in terror, and that “her head was filled with screams.”

After reading the text in my office and trying to connect with the emotions in it, M recalled the following “forgotten” memory: “I was at a house with a swimming pool, accompanied by some friends. My one-and-half-year-old son was playing at the edge of the pool, which was still dirty from the winter months. I had to go into the house and go up to the second floor. I checked on him before going in. There were other adults in the garden. Once I was upstairs, I went over to the window, I was feeling uneasy, and I saw him fall in headfirst. I didn’t scream. I ran back downstairs and threw myself into the pool shouting ‘Oh my God!’ I got him out, although I needed some help, and gave him mouth to mouth resuscitation and he recovered. For a long time afterwards, when I closed my eyes the scene would reappear in my mind and I would be overwhelmed by a feeling of panic.”

A whole world of repressed emotions opened up. The activation of the semantic, sensorial, and emotional aspects of this representation set in motion a chain of activation of other representational nodes that shared a closeness or similarity. The situation opened a discussion of the times when motherhood was distressing for M. She told of how her second child had febrile convulsions and how there had been a period during which she would phone his nursery more than 10 times a day to see how he was. On one occasion she commented, “I was driving to a telephone box to call the school to check on the children, and I was in such state by the time I got there that I ran straight into it… It was a difficult time, it was lucky that the head of the kindergarden knew how to deal with it and was able to calm me down.”

Rereading the text in session created a MoHR in which M was able to connect with her feelings of anxiety associated with maternity. This in turn opened the door to another related, and even further distant, feeling: her mothering relationship with her younger siblings. We must consider that M had to look after five siblings when she was barely 10 years old. As adults M’s siblings had lives filled with conflict. They were probably marked by their bond with their neglectful parents and where M, in the substitute-mother role, proved insufficient. Furthermore, this had the effect of a double trauma for M; she not only had feelings of guilt and abandonment for failing her siblings, but also she failed to register her own abandonment at having to take on the adult role. It is likely that this reinforced the mechanisms of dissociation, as perceiving her own anguish in this scenario presented a threat to her integrity and her efforts in that role.

In another session we used a photo from M’s childhood. In it she is sitting in the center of the picture, holding her youngest sister on her lap; the rest of her younger siblings surround her. Working with this photo had a similar effect to reading the passage from the novel. It created a MoHR, and this allowed us to reconnect to an emotional state, which in turn accessed other dreams and associations. The result was an amplified capacity for M to connect with her feelings of anguish and her need to be taken care of, both of which had been practically nonexistent until that moment.

The vignette emphasizes the enormous effectiveness of MoHR in achieving therapeutic change that is caused by feelings that are undeniable to the patient and the therapist. This is because the feelings are manifested in the context of the session and because of their vivid and experiential character. The clinical work no longer consists of overcoming resistance to these feelings; rather the feelings acquire the character of known facts. Irrespective of the strong evocative power and the painful feelings MoHR may give rise to, we can work from there, going back at different points in subsequent work and evoking these moments, to take up another aspect of them again. We want to stress that using it as an experiential bookmark in the therapeutic process allows us to regulate the amount of emotion that our patient can tolerate in any given time.

We are talking about a situation that encompasses the patient and the therapist, the transferential-countertransferential processes, and the surrounding environment.

An example of the differences between moments of low and high receptiveness is the difference between telling about a dream in the conventional way in the past tense and telling about the same dream in the present tense, in an experiential way (de Iceta & Méndez, 2003). In the first scenario of [telling about] the dream, certain associations come across. When the dream is told again as if it were happening in the now, thus increasing the experiential nature of the telling, the number of active mnestic elements is amplified and new associations, along with new connections, appear. The result is that the appearance of this new material, together with its new experiential quality, increases the receptiveness to the technical interventions referring to these elements of “new appearance.”

In short, we are looking at the old Freudian difference (1915), by referring to mental content—between what is experienced and what is heard—as very different ways of processing and working with representations. We would then say that states exist in which receptiveness or accessibility is high, as opposed to others which do not provide these conditions. We are not referring to a general receptiveness/accessibility, but one that is concrete and specific, and tied to contents that are linked by unconscious processes active in that moment.

It is up to the therapist to take advantage of these accessible moments, however, because MoHR are moments of high vulnerability for the patient, there is a substantial risk of iatrogenic consequences. We draw a parallel between the dose of medication to be administered either orally or intravenously; the former allows for a wider dose adjustment, but change is slower; the latter is faster and more efficient with regard to change, but requires much finer adjustment because of the higher risk of inflicting harm.