College-age students are generally at increased risk for experiencing psychopathology (

1–

3). They are at an age when first episodes of depression, bipolar disorder, or psychosis often occur. Moreover, in many cases they have little social support available to them, as they are often—and frequently for the first time—living away from their familiar social and family networks. This period, nestled between adolescence and adulthood, is also a vulnerable developmental stage, rife with academic and social stressors. On one hand, this period of emerging adulthood (

4) is a unique time, full of opportunity to explore, marked by greater freedom and independence, and relatively free of the responsibilities brought on by mature adulthood (

5,

6). On the other hand, not everyone enters this period equipped with the skills needed to navigate the transitions it brings, such as independent decision making and self-care, forging new social connections, connecting with appropriate support systems, and coping amidst profound changes (

6,

7). For these reasons, most university campuses offer some counseling and support services to their student population.

Recent years, however, have seen profound changes in the volume and nature of referrals handled by university counseling centers (

8). Dramatic increases in the number of students seeking treatment at such centers (

9,

10) have been accompanied by a sharp rise in the severity of symptoms reported by these students (

1,

11–

13). Prevalence rates of depression among college students have been found to be higher than those of the general population. For example, one systematic review (

14) of studies has estimated the rate of depression among students to be as high as 30%. The high demand for treatment inevitably leads counseling centers to prioritize providing care to students with more urgent cases. Consequently, students with mild to moderate depression may experience longer wait times, receive fewer counseling sessions, or both (

15–

17). Unfortunately, depression symptoms may worsen if treatment is delayed (

18). This problem could be alleviated, at least in part, if counseling centers implemented brief interventions appropriate for this large group of students in need. (Note that in this article, we use the term “university” to refer to postsecondary educational institutions and the term “college” or “college aged” to refer to students at such institutions, whether they are pursuing undergraduate or graduate degrees).

To develop interpersonal counseling for college students (IPC-C), the first author (A.K.R.) began by using the then-available version of the interpersonal counseling manual (

19,

20). IPC is a modification of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (

21–

23) and is itself a short-term, evidence-based psychotherapy for major depressive disorder and other psychiatric conditions. IPT and IPC focus on the patient’s current life events, including social and interpersonal functioning, as a means of understanding and treating depressive symptoms (

24). Unlike IPT, IPC was intentionally designed to be delivered in a briefer and more flexible manner, often by non–mental health workers. Specifically, IPC was initially developed for use by nurses in primary care settings as a tool for screening and intervening in depression (

25). Over time, it was further adapted for use in other non–mental health settings where professionals may have direct contact with individuals at risk for depression (

20). Additional adaptations of IPC (

26) have taken a transdiagnostic approach to treat symptoms of distress, both physical and mental, across diagnoses. IPC was chosen as the foundation for this work because its model and treatment characteristics offered a good fit for the needs of university counseling centers in this era of large patient volume and insufficient resources. Furthermore, one study had examined IPC within a university counseling environment. In that randomized controlled crossover trial conducted with Japanese undergraduates reporting subthreshold depression, Yamamoto and colleagues (

27) compared IPC to counseling as usual. The IPC group (but not the counseling-as-usual group) was found to have a significant decrease in depressive symptoms and marginally better self-reported coping.

The IPC-C manual used in the present study included several adaptations to the intervention’s length, pacing, and target population. IPC-C was designed to provide three to six counseling sessions for students with mild to moderate depression, with specific guidance to reduce the time between sessions when possible. This recommendation was based on several recent studies (

28–

30) suggesting that closer spacing of evidence-based treatment sessions improves overall depression outcomes. Importantly, this finding runs counter to common practice in counseling centers, in which treatment-seeking students are often waitlisted or seen less frequently, according to symptom severity.

IPC-C also incorporated techniques drawn from interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents with depression (IPT-A) (

31), which are well suited for treating emerging adults, and addressed the development of specific skills relevant to this population (e.g., self-care and forming social connections). These considerations are described further in the Methods section below. All adaptations were made to address characteristics that are common to students seeking help in college and university counseling centers (at least in North America), including considerable co-occurrence of mild depression with social anxiety, both of which can be exacerbated when students move away from home to a college environment.

Methods

Study Overview

We set out to conduct a pilot study examining the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of IPC-C. Our a priori expectation was a ≥80% retention rate and an average satisfaction score ≥5 on a 6-point satisfaction scale, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. We also expected to find a clinically significant reduction in depressive symptoms and a rise in adjustment to college life.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were 10 students seeking treatment (January through June 2017) at the counseling centers of two separate higher education institutions located on the U.S. East Coast. Approval was obtained from both institutions’ institutional review boards, and consent was obtained from all participants. The inclusion criterion was a Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) score of 5–14, which reflects mild to moderate depression. Exclusion criteria were any significant risk of danger to self or others, as well as any diagnosis of a psychotic, eating, or substance dependence or use disorder. If participants were to develop more severe depression (defined as a PHQ-9 score ≥15), they would be withdrawn from the study and referred for necessary and appropriate care; this did not occur with any of the participants. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 28 (mean±SD=20.0±2.0). Most of the participants were women. At both counseling centers, diagnostic impressions were obtained thorough intake interviews. All participants were assessed as having one of the following conditions: dysthymia, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, major depressive disorder, or bereavement. Participants ranged from first-year students to graduate-level students.

Measures

Feasibility and acceptability.

Feasibility was assessed by using the rate of study completion among intent-to-treat participants. Acceptability was assessed with the IPC Satisfaction Scale, which includes 10 Likert-scored items (ranging from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction) inquiring about the therapeutic alliance, satisfaction with the length and frequency of sessions, and overall satisfaction with IPC-C. This measure, completed after the last session, was modified from the satisfaction questionnaires used in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (

32) and the Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy for Adolescents with Bipolar Disorder study (

33).

Depressed mood.

Depression was assessed with the PHQ-9 (

34), a self-report depression screening and severity instrument, which has demonstrated good reliability and validity. PHQ-9 scores of 5–14 reflect mild to moderate depression, and scores ≥20 reflect severe depression. The measure was completed at the beginning of every IPC-C session.

Social functioning.

The College Adjustment Test (CAT) (

35), a 19-item self-report scale, was used to assess adjustment to college. It is composed of three subscales that reflect participants’ adjustment-related positive affect (e.g., “liked your roommate[s]”), negative affect (e.g., “felt depressed”), and levels of homesickness (e.g., “missed your home”) over the past week. The measure was completed prior to the first session and after the last session. Responses were reported on a 7-point Likert-type scale. Negatively worded items were reverse-scored to obtain a total adjustment score.

Intervention

IPC-C was developed for use with students receiving services in university counseling centers. This intervention adheres to the core components of IPT and IPC (

26), spanning three treatment phases (initial, middle, and termination). (The unpublished manual is available by request from the first author [A.K.R.].) During the initial phase, the therapist provides psychoeducation about depression, likens it to a medical illness, and conducts an interpersonal inventory, which is a register of the key relationships in the individual's life. Through the interpersonal inventory, the patient’s social functioning problems are identified and then attributed to one of four problem areas: role disputes, interpersonal role transitions, interpersonal deficits, and grief. In the middle phase, the therapist focuses the work on resolving social functioning problems (e.g., by practicing alternative methods for communication, recognizing and regulating affect, or problem solving interpersonal challenges). During the termination phase, the therapist notes the patient's accomplishments, jointly explores with the patient how he or she can continue applying the acquired skills once therapy has concluded, and acknowledges the patient’s (often mixed) feelings about termination. Together, the therapist and patient also assess whether referral for additional psychotherapy or other mental health intervention is warranted.

Some characteristics of the target population led us to go beyond IPC and to incorporate additional ideas into what became the IPC-C manual. First, because college students are typically undergoing the developmental stage referred to as emerging adulthood (

4), we reasoned that clinical work with them should also draw from interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (IPT-A) (

31). Relatedly, IPC often addresses the patient’s “sick role,” which helps allay some of the guilt inherent in depression. We found that for this patient population, the IPT-A concept of a “limited sick role” offered a better fit, promoted a sense of agency, and helped take into account broader identity formation processes (

36), such as intersectionality (

37,

38). Third, depression, both in general (

39,

40) and in this target age group (

41–

43), is often comorbid with anxiety disorders; in particular, the social challenges of adolescence and emerging adulthood and the transition from home life to college life often have the most severe impact on socially anxious individuals (

44). As such, we applied lessons learned from efforts to address social anxiety with IPT (

45). Additionally, because cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is often effective in treating social anxiety (

46), we incorporated some optional CBT techniques (

47) to be used if clinically indicated. Finally, university life often involves daily stressors, frequent exam periods, academic assignments, and heavy reading loads. Students are expected to possess self-discipline and adequate time management skills while effortlessly and perfectly balancing their schedules to socialize, forge new relationships, and set long-term personal and professional goals. We found it important to provide our student patients with tools that would help them cope with such serious, although common, stressors. For this reason, the adaptations included a self-care checklist to help ensure that students followed healthy routines (i.e., healthy eating, sleeping, and regular exercise) (

48) known to affect mood. (For further information about the development of the IPC-C manual or for the manual itself, please contact the authors.)

For this study, three clinicians delivered IPC-C. At one counseling center at a 4-year liberal arts college, IPC-C was delivered by the developer of the intervention. At the other counseling center at a university, IPC-C was delivered by two psychology interns trained in the approach. Prior to implementation of the study, these two clinicians attended a 1-day IPC-C training workshop. Two authors (A.K.R., L.M.), both certified trainers and supervisors in IPT, reviewed all audio-recorded sessions for fidelity to the IPC-C manual. This review served as the basis for weekly supervision conference calls with these two authors and the two additional therapists and were held for the duration of the study. IPC fidelity checklists were completed for the trainee therapists’ audio-recorded sessions. Fidelity ratings averaged 3.39 on a scale of 1 to 4 (3, satisfactory; 4, superior).

Results

Retention and Satisfaction

Nine of the 10 participants (90%) completed the study; we were unable to follow up with one participant who dropped out after two sessions. Despite efforts made by the therapist, there was no response after dropout; therefore, we have no information regarding the student’s reason for leaving therapy. No participants were withdrawn from the study for an elevated PHQ-9 score above 14. Among completers, the mean number of therapy sessions attended was 5.4±0.7 (range 4–6), over an average of 5 weeks (range 2–10). On average, completers found the intervention to be quite satisfactory; all satisfaction scores were above the midpoint of the 0–6 scale (denoting moderate satisfaction). The scores ranged from 3.8 to 6.0, with a high average (mean=5.1±0.7).

Symptoms and Support Measures

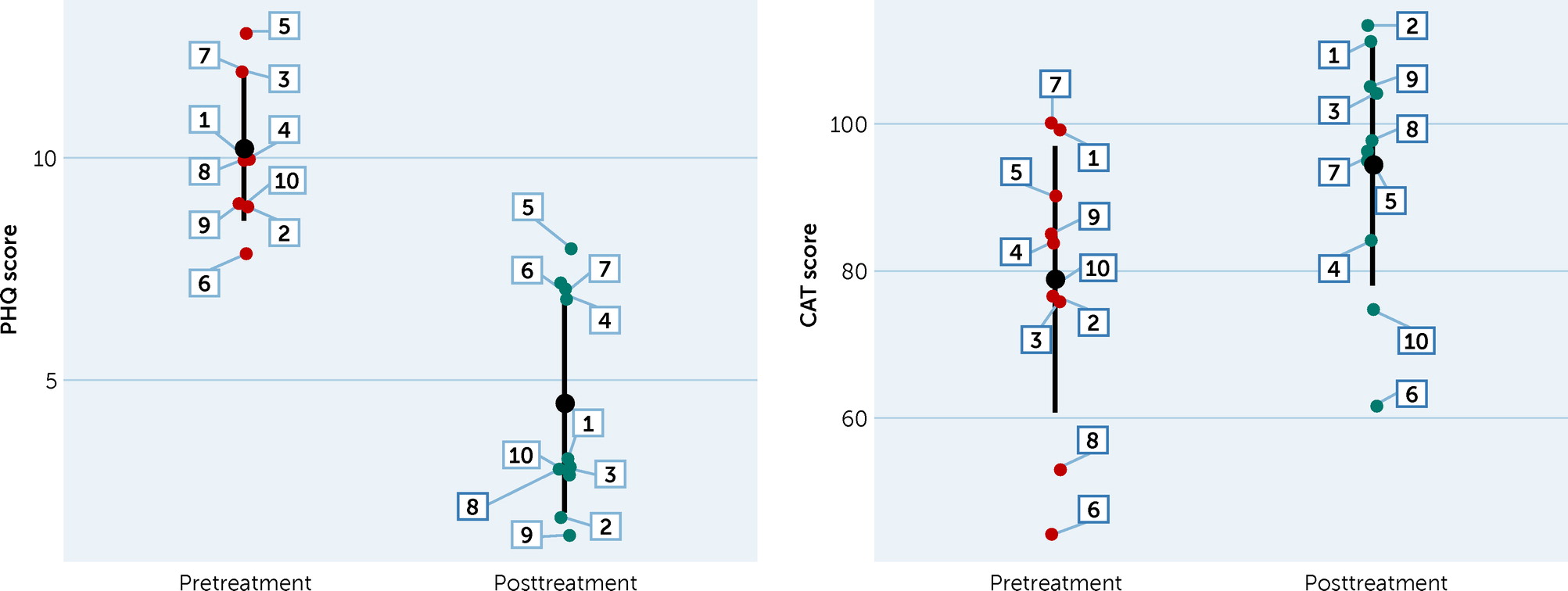

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and scores of the participants’ PHQ-9 and CAT scores, pre- and posttreatment. One participant (labeled 4 in

Figure 1) dropped out after the second session; therefore, his last scores were carried forward. Paired t tests showed that posttreatment PHQ-9 scores (mean=4.45±2.5) were significantly lower than pretreatment scores (mean=10.2±1.6; t=–7.74, df=9, p<0.001). The estimated effect size of the PHQ-9 from baseline to termination was very large (Cohen’s d=2.45). Of note, 80% (N=8) of the patients demonstrated a reliable change (

49) in their depressive symptoms during the treatment (a decline in PHQ-9 score of at least 5 points), and 60% (N=6) of the patients showed depressive symptoms below the clinical threshold (score <5) after the treatment (

33,

50). We also performed a multilevel regression analysis, in which patients’ session-level PHQ-9 reports were regressed on session number. In this model, the intercept and slope (i.e., session number) were estimated as both fixed and random effects. The results indicated that the patients showed a significant linear decrease in depressive symptoms over the course of treatment (estimate=–1.25, SE=0.22, p<0.001).

Paired t tests showed that posttreatment CAT scores (mean=94.3±16.25) were marginally higher than pretreatment scores (mean=78.7±18.06; t=2.90, df=9, p=0.017). The effect size of this pre-to-post increase in adjustment was large (Cohen’s d=0.92).

We performed a set of regression analyses to test whether changes in patients’ depressive symptoms and college adjustment were associated with pretreatment depression level (mild versus moderate), number of therapy sessions received, patients’ age, and patients’ years in school. None of these variables were significantly associated with levels of change. Complete results can be obtained from the first author (A.K.R.).

Discussion

The objective of this pilot study was to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of IPC-C in the treatment of students with mild to moderate depression receiving psychotherapy in university counseling centers. The feasibility of delivering the treatment was supported by the high completion rate. The acceptability of this brief evidence-based psychotherapy was supported by participants’ reported satisfaction with the therapy; specifically, the participants found the number of sessions involved (within the intended 3–6 session range) to be acceptable. Finally, the efficacy of the approach was supported by the large effect sizes found for reduction in depression and increase in adjustment.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the study was conducted in two university counseling centers on the East Coast of the United States, which may have limited the generalizability of the results for counseling centers in other geographic areas as well as for other student populations. Second, the sample size of this unfunded pilot study was small and thus limited the statistical power. The sample size of this study was determined by the availability of both counselors and participants. As such, it reflected a problem present at both sites, wherein the counselors’ caseloads were often overwhelmed by urgent crisis-focused referrals, delaying treatment for potential participants with mild to moderate depression who may, in some cases, have sought treatment outside the counseling centers. It is precisely this patient group that is currently underserved in college counseling centers (

51), and it is with them in mind that we developed this intervention. Our hope is that, through the adoption and implementation of IPC-C or other brief evidence-based approaches, students will be able to receive a timely response to their depression while it is mild or moderate in severity, rather than arriving on the doorstep of a counseling center in crisis. After all, depression often worsens if treatment is delayed. Thus, prompt identification of symptoms and of the problems associated with their onset, coupled with briefer evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions, may help students mobilize resources and prevent further sequelae of depression.

The limitations in the generalizability and power of these findings call for further testing of the IPC-C approach to replicate these early feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy results. A replication would also remedy another limitation of the present study, which was that the first author (A.K.R.) served as a therapist at one site and as a trainer and supervisor at the other site. In particular, it will be beneficial to conduct strongly powered randomized controlled studies within diverse institutions and student bodies. Such work will help determine whether the current IPC-C manual should be further adapted for specific subpopulations or settings.

Conclusions

College counseling centers are struggling to meet the increased demand of more students with critical, high-risk conditions. Consequently, although depression is highly prevalent among college students, the availability of regular psychotherapy appointments for those experiencing mild to moderate depressive symptoms has decreased to make room for more urgent care appointments and crisis interventions. To help address this gap, we adapted IPC in both content and structure to create the IPC-C manual tested here. We reasoned that the characteristics of IPC-C may offer a good fit for the needs of college students with mild to moderate depression and for the university counseling centers which often struggle to meet these needs. Our results, and particularly the high acceptability and strong efficacy obtained, reflect this reasoning and suggest that further exploration of the IPC-C approach and its implementation is warranted.

With the emergence of the global COVID-19 crisis and its effects on higher education institutions (resource depletion, closures, and a move to distance learning) and on the students themselves (financial, occupational, health concerns, and uncertainty), we believe IPC-C has become even more relevant. Clearly, problem areas troubling these patients (e.g., role transitions, interpersonal disputes and deficits, and perhaps even grief) have been exacerbated by the health concerns, limited social opportunities, communication difficulties (e.g., mask wearing), and loss of loved ones to COVID-19 that are now a global reality. IPC-C provides a brief alternative to more traditional counseling approaches and could be easily adapted to teletherapy.