Despite the many available and effective treatment options for depression (

1,

2), a substantial number of individuals do not achieve remission (

3,

4). Because individual treatment responses vary and are highly unpredictable, identifying risk factors associated with treatment outcome may help to personalize treatment selection and subsequently improve remission rates (

5,

6). In addition to known risk factors for treatment resistance, including high depression severity and chronicity of the index episode (

7,

8), the presence of comorbid personality disorder is often considered (

9,

10). Its relevance is potentially large because personality disorders are a common comorbid condition of outpatients with depression (

11,

12).

Two frequently cited meta-analyses (

13,

14) have reported that personality disorders negatively affect acute-phase treatment outcomes in depression, concluding that the presence of these disorders is important in the prognosis of depression. In contrast, a review by Mulder (

15), which focused solely on controlled studies, found no negative effects of personality disorders. According to Mulder, this difference in findings could be explained by patients with these comorbid conditions receiving less optimal treatment in uncontrolled studies, because such studies are likely biased by clinicians who regard a personality disorder as a relevant factor in treatment selection. Three meta-analyses have contributed to Mulder’s hypothesis, indicating no significant differences in outcomes between individuals with and without personality disorders in controlled trials of pharmacotherapy (

16,

17) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (

18) for depression. Their findings have been replicated and extended by a recent meta-analysis (

19) that focused on treatment outcomes in only well-designed controlled trials of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for depression. Results showed no significant differences between individuals with and without comorbid personality disorders in terms of average depression severity change and rates of response and remission (

19). Because individuals with personality disorders appear to have better treatment outcomes in studies with controlled treatment selection, the less satisfactory outcomes of naturalistic designs may be incorrectly attributed to the comorbid condition, instead of to insufficiently provided depression treatment. On the basis of these meta-analyses (

16–

19), one could hypothesize that with care as usual, treatment provision may be less optimal for individuals with personality disorders. However, only a few older studies (

20,

21) have reported on this issue, indicating that individuals with comorbid personality disorders receive less pharmacotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression, compared with counterparts without comorbid personality disorders. Recent studies addressing this research question are lacking.

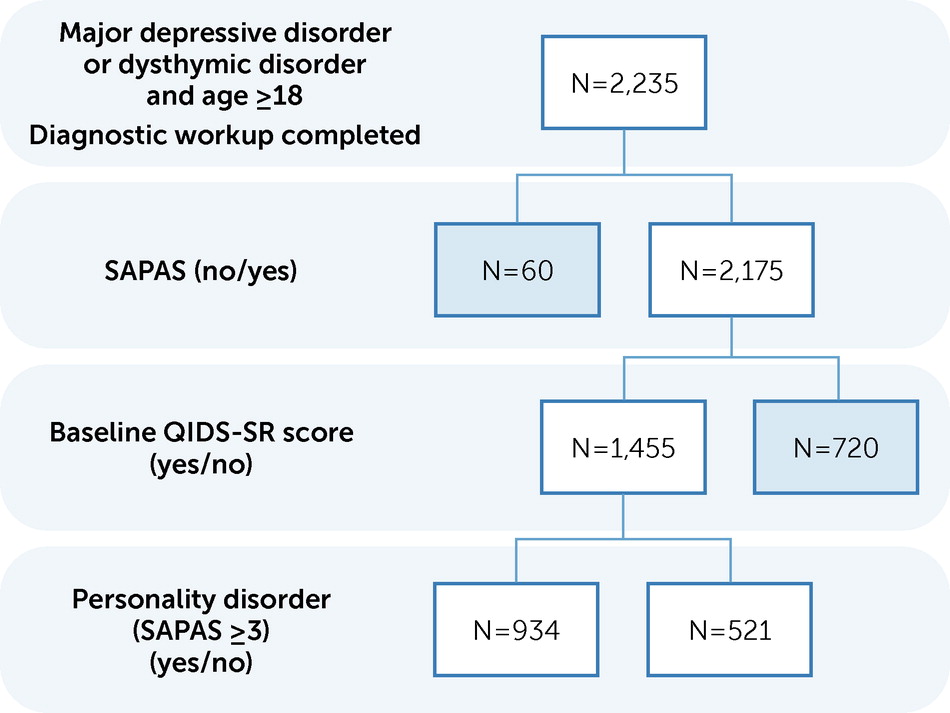

The aim of the current study was to examine whether, and to what extent, the presence of comorbid personality disorders was associated with the type and number of treatment sessions received in the context of naturalistic outpatient depression care. First, we examined whether individuals with comorbid personality disorders received different types and intensities of depression treatments than those recommended by international and national evidence-based guidelines (i.e., psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, a combination of both, or ECT [

22–

24]). We hypothesized, on the basis of the limited evidence available on the receipt of less pharmacotherapy and ECT among individuals with depression and comorbid personality disorders, that these individuals would receive less optimal treatment (i.e., fewer therapy sessions, particularly for pharmacotherapy) than individuals with depression and no comorbid personality disorders, irrespective of the level of depression severity. Second, we investigated whether comorbid personality disorders affected the number of other types of care received. We hypothesized that individuals with depression and comorbid personality disorders would be more likely to receive a greater number of supportive and crisis visits than individuals without comorbid personality disorders.

Discussion

The present retrospective observational study investigated whether, and to what extent, comorbid personality disorders were associated with the amount and type of treatment for depression received by 1,455 outpatients. Our main finding was that individuals with depression and comorbid personality disorders received more psychotherapy sessions and therefore more intensive treatment than individuals without comorbid personality disorders, irrespective of initial depression severity. In addition, there was no difference in the number of pharmacotherapy sessions, supportive visits, and crisis visits for depression between individuals with and without comorbid personality disorders.

The finding that individuals with depression and comorbid personality disorders received more psychotherapy sessions for depression was not in line with our hypothesis or with previous findings. Earlier studies (

20,

21) have indicated that individuals with depression and comorbid personality disorders are less likely to receive evidence-based treatments, including ECT and antidepressant medication, than individuals without comorbid personality disorders. However, recent evidence addressing this issue is lacking. The results of our study also conflict with international and national evidence-based guidelines. These guidelines (

22–

24) demonstrate a consensus that treatment strategies for depression should not vary based on depression subtypes or individual characteristics, such as comorbid personality disorders. One exception is depression severity: antidepressant medication (with or without psychotherapy) is considered to be the treatment of choice for individuals with severe depression, although the guidelines are not entirely consistent (

31). In the present study, the total number of pharmacotherapy sessions was indeed related to baseline depression severity.

The finding that individuals with comorbid personality disorders did not receive more supportive and crisis visits did not align with our secondary hypothesis. Because individuals with comorbid personality disorders can have more interpersonal problems (

32), lower social functioning (

33), and suicidality (

34), we expected them to receive a greater number of supportive and crisis visits. However, one could speculate that these visits were prevented by or handled within the greater number of psychotherapy sessions.

A key question underlying our findings is whether the greater number of psychotherapy sessions is either a required solution for a complex clinical problem or an unnecessary intervention that adds to overtreatment of depression (

35). The complexity of individuals with comorbid personality disorders in this sample was reflected by their initial clinical presentation with more depressive and anxiety symptoms, longer episode duration, and higher incidence of childhood trauma, which has been found in previous research (

36–

38) as well. One could speculate that therapists feel that extension of treatment increases the odds of a good outcome for patients with these complex conditions (

39). This opinion is supported by a recent meta-analysis (

18) that describes an association between adequate treatment duration (16–20 sessions) and treatment effects among individuals with comorbid personality disorders receiving cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Another possible explanation could be that the greater number of psychotherapy sessions was an indicator for the responsiveness of therapists to the comorbid personality disorder; possibly therapists were unconsciously focusing on personality disorder symptoms. In addition, the finding could also indicate that patients with comorbid personality disorders needed to receive more sessions for the process of ending the therapeutic relationship. However, despite the complex clinical problems, a significantly greater number of psychotherapy sessions could be a sign of overtreatment. First of all, the association between the number of psychotherapy sessions and a favorable outcome in depression is not significant and very small (

2). In addition, although sufficient treatment duration has been shown to be associated with better depression outcomes for individuals with comorbid personality disorders, a sufficient duration has been defined as 16–20 sessions (

18). This range was exceeded in our study, which found the average length of psychotherapy to be 22 sessions. Moreover, findings from well-designed studies (

16–

19) with controlled treatment have not indicated that comorbid personality disorders negatively affect acute-phase depression outcomes; therefore the need for additional therapy remains questionable. Given the current problems in the timely availability of treatment in Dutch mental health care (

40,

41), it is important not to unnecessarily extend therapy.

Although this study provided an interesting look at daily mental health care practice, there were some limitations. First, a substantial number of participants did not have a baseline QIDS-SR or SAPAS assessment and had to be excluded from the analyses. However, pretreatment comparisons indicated that these individuals did not significantly differ from those included in the analyses. Second, the presence of personality disorders was determined by a brief standardized clinical interview (i.e., SAPAS) (

26,

27) and did not provide information on the different types of personality disorders. Validated methods, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II (SCID-II) (

42), may be more appropriate for studying personality disorders. However, time and resources for the use of such instruments are typically not available in routine depression care. Considering this limitation, we think that the SAPAS is an appropriate compromise between the need for a validated instrument and the need for representativeness of diagnostic assessments in daily clinical practice. The third limitation concerns the lack of information on how treatment decisions were motivated; it is possible that the clinicians decided explicitly that more psychotherapy sessions were indicated because of the comorbid personality disorder status, but we cannot exclude other reasons for the positive association between the comorbidity and the number of psychotherapy sessions. The fourth limitation involves the information on the received depression treatment. Although reliable data on the type and number of depression treatment sessions were available, details were lacking, including information on the quality of the psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy and switches between different types of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. The fifth limitation concerns generalizability. Although our study sample came from several treatment sites within a nationwide organization in the Netherlands, these results may not be generalizable to all mental health care settings.