Epidemiology

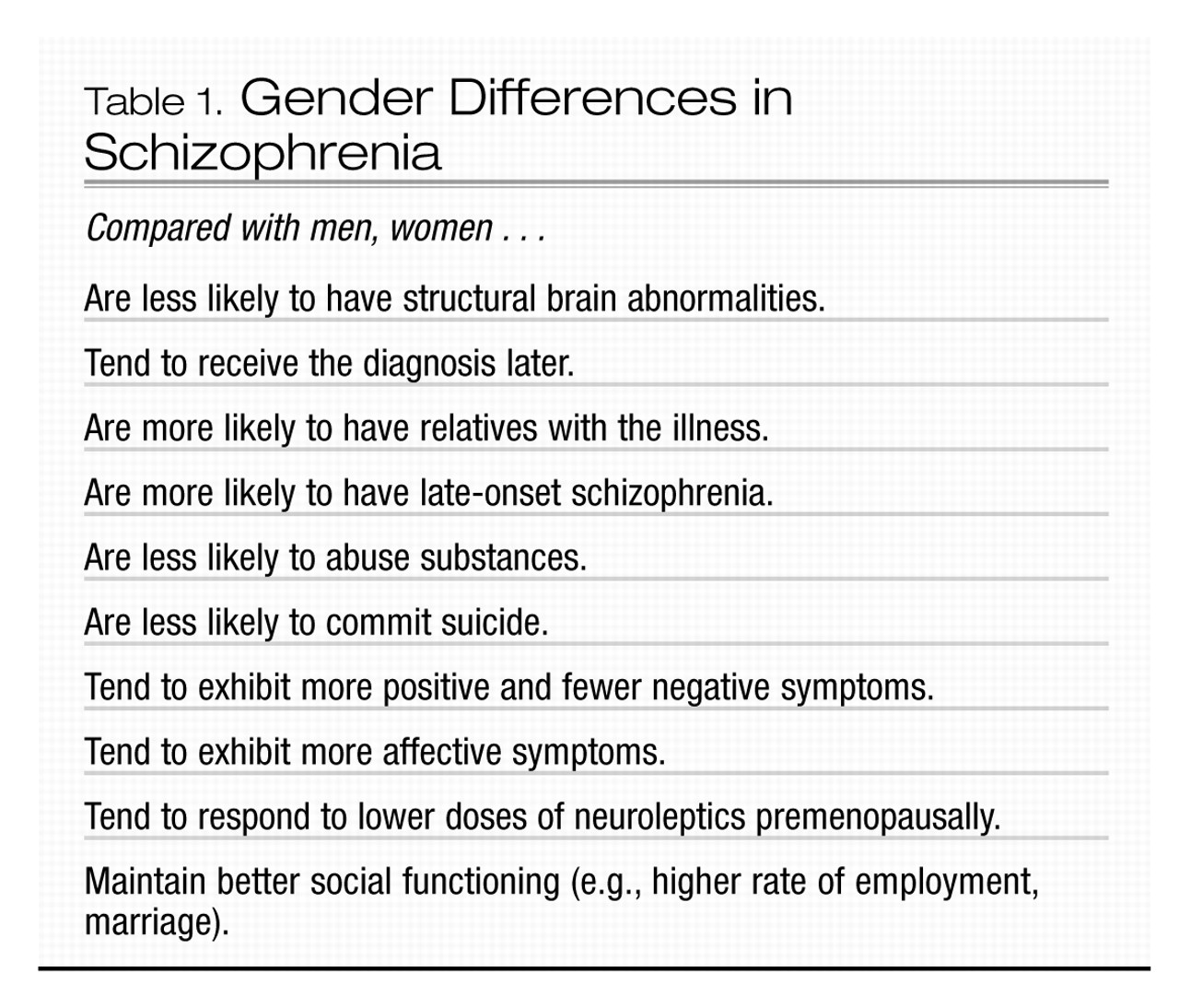

Significant gender differences exist in the course and manifestation of schizophrenia. Although the incidence of schizophrenia has been widely reported to be approximately equal in men and women, a recent meta-analysis of the literature from the past two decades reported that the incidence risk ratio for men relative to women is between 1.31 and 1.42 (

Aleman et al. 2003). The authors of this study suggested that these findings may reflect an increasing preponderance of schizophrenia in men in recent years. This increase may be related to the use of illicit drugs, which may precipitate the illness in genetically vulnerable men. Because oral contraceptives contain estrogen, which has dopamine-blocking effects in animal studies, the use of these agents may have had a protective effect in some women.

In men, rates of new-onset schizophrenia reach a peak between ages 15 and 24 years. For women, the peak occurs between ages 20 and 29 years. About 15% of women with schizophrenia do not develop the illness until their mid- or late 40s, possibly reflecting a response to the perimenopausal decline of estrogen (

Aleman et al. 2003) (Table 1). For men, onset of the illness after age 40 years is rare. The diagnosis of schizophrenia is more likely to be delayed in women, in some cases possibly because of misdiagnosis of either major depression or bipolar disorder, as schizophrenia in women tends to be more affect-laden (

Seeman 2004).

Other gender differences include a more favorable premorbid history in women and more favorable outcome, at least in the first 15 years after onset of the illness (

Grigoriadis and Seeman 2002;

Seeman 2004). Women with schizophrenia tend to experience more affective and positive symptoms and fewer negative symptoms (e.g., social withdrawal and lack of drive) than men. In addition, women who present initially with schizophrenia after age 45 years typically suffer fewer negative symptoms than either men of the same age with schizophrenia or age-matched women with early-onset schizophrenia (

Lindamer et al. 1999). Structural brain abnormalities, such as increased ventricle size and decreased hippocampal volume, appear to be less common in women with schizophrenia than in men with the disorder (

Cowell et al. 1996). Because relatives of women with schizophrenia are more likely to develop the illness, compared with relatives of men with schizophrenia, some researchers have suggested that schizophrenia is a more heritable illness in women and that environmental factors, such as birth complications, may be of more etiological significance in men (

Castle and Murray 1991).

Special considerations in treatment

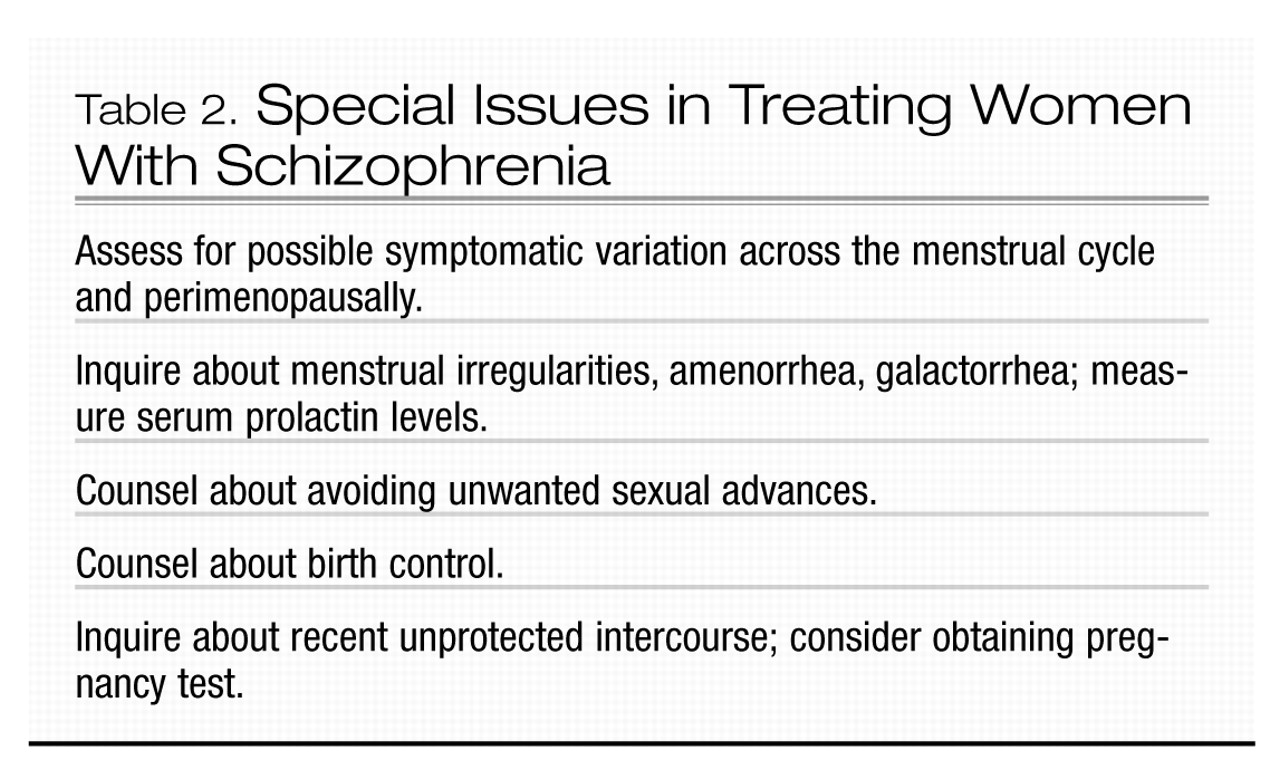

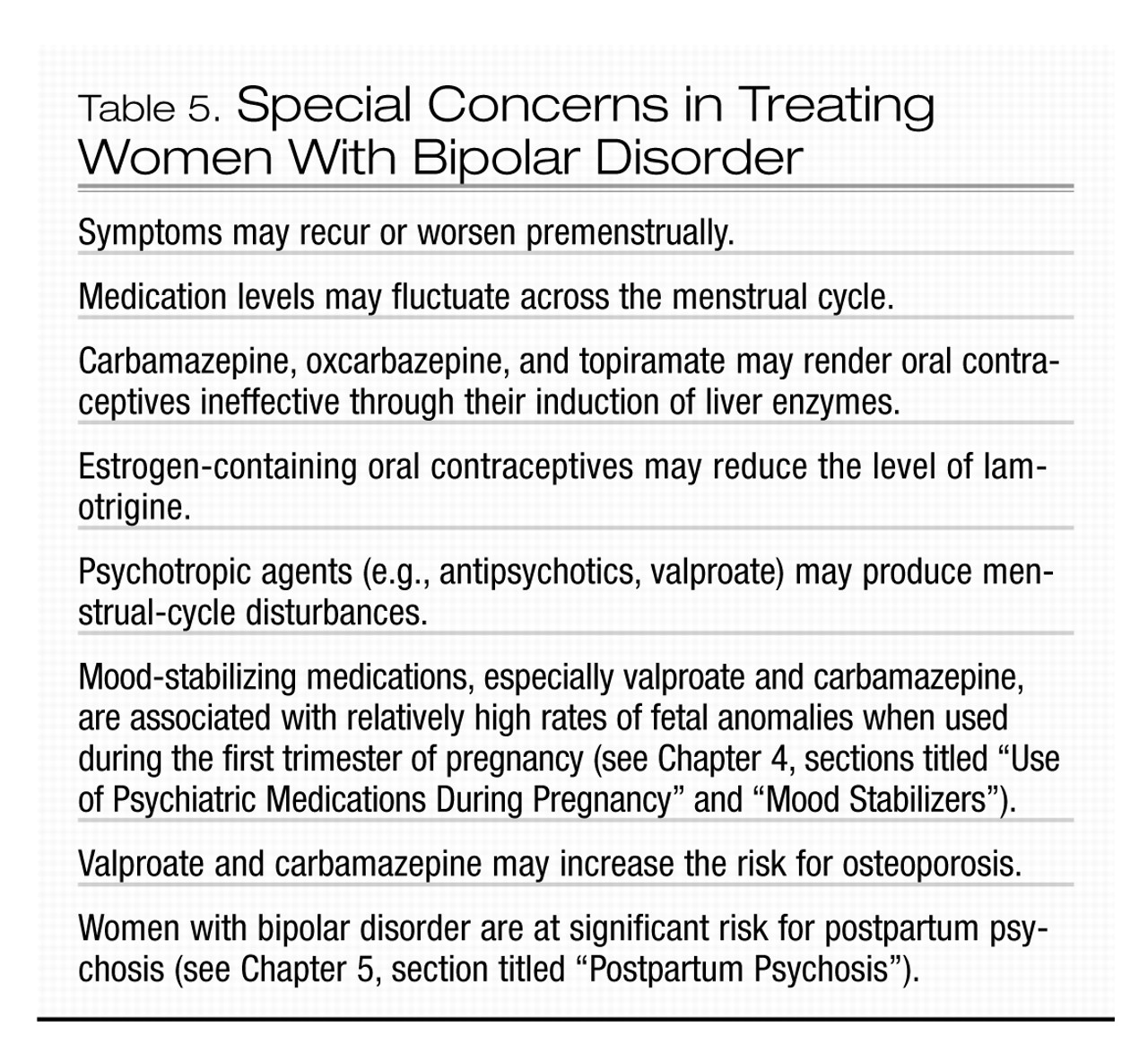

Issues in the treatment of women with schizophrenia are listed in Table 2. Some, but not all studies suggest that, compared with men, women respond better to treatment and may require lower doses of medication before menopause (

Seeman 2004). Findings of a more favorable treatment response and course of illness in women have supported the speculation that estrogen may have a protective effect against schizophrenia (

Szymanski et al. 1995). It is noteworthy that symptomatic exacerbation of schizophrenia and an increase in psychiatric hospital admission rates have been observed during the low-estrogen phases of the menstrual cycle (

Bergemann et al. 2002;

Choi et al. 2001;

Seeman 1996;

Szymanski et al. 1995) and in perimenopausal and postmenopausal years (

Seeman 1986).

The menstrual patterns of women with schizophrenia should be monitored routinely. Careful clinical monitoring of symptoms in relation to the menstrual cycle, perhaps with the use of a diary, may be useful. If such monitoring indicates pre-menstrual worsening of symptoms, exacerbation of symptoms may be minimized by raising antipsychotic doses during the symptomatic pre-menstrual days. Women with schizophrenia should also be monitored carefully for worsening illness as they transition into menopause, as it may be necessary to increase antipsychotic doses at this time.

In a small double-blind, placebo-controlled study of acutely symptomatic premenopausal antipsychotic-treated women with schizophrenia, the use of transdermal estradiol as an adjunctive treatment resulted in significant improvement in psychotic symptoms (

Kulkarni et al. 2001). Further studies are needed to determine whether estrogen may have a role as an adjunctive agent for the treatment of women with schizophrenia. Estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women has been associated with increased risks for cardiac events, pulmonary embolism, stroke, dementia, and breast cancer (

Rossouw et al. 2002), and therefore estrogen therapy should not be used for the treatment of psychiatric symptoms unless its benefits clearly outweigh its risks.

Certain antipsychotic medications (e.g., risperidone, haloperidol, fluphenazine) can cause irregularities in the menstrual cycle by increasing levels of the pituitary hormone prolactin, which in turn inhibits release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary. As FSH is necessary for maturation of the ovarian follicles, a hyperprolactinemic state can prevent ovulation. Furthermore, hyperprolactinemia and the ensuing hypoestrogenemia can lead to a reduction in bone mineral density (

Seeman 2004). Amenorrhea (i.e., absence of the menstrual cycle) is not unusual when prolactin levels exceed 60 ng/mL (normal prolactin levels are 5–25 ng/mL) (

Seeman 1983). Galactorrhea, or nipple discharge, may also occur with elevated prolactin levels. If prolactin levels exceed 100 ng/mL, a brain-imaging study (preferably magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), should be performed to rule out a prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Additional causes of elevated prolactin include pregnancy, nursing, stress, weight loss, opiate use, and use of oral contraceptives (

Marken et al. 1992). For women of childbearing age with menstrual cycle disturbances, β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) levels should be measured to test for pregnancy. Other relatively common causes of irregularities in the menstrual cycle include hypothyroidism and primary hyperprolactinemia. If hyperprolactinemia is determined to be secondary to the use of an antipsychotic agent, the dose should be reduced or the medication should be replaced with one of the newer antipsychotic agents, such as olanzapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, or quetiapine, which do not tend to raise prolactin levels. As an alternative, dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine (2.5–7.5 mg bid) or cabergoline (0.5 mg/week) can be used to reduce prolactin levels. At these low doses, bromocriptine does not appear to exacerbate psychosis. The effect of cabergoline on psychotic symptoms has not been evaluated. Cabergoline requires only once or twice weekly dosing and produces few side effects, whereas bromocriptine must be taken daily and can cause significant nausea. To minimize the nausea, bromocriptine should be taken with food. A third strategy is initiation of an oral contraceptive. This approach returns the patient to regular menstrual cycling and, by restoring estrogen, protects against the long-term adverse effects of a hypoestrogenic state, such as osteoporosis. In addition, this approach has the advantage of providing contraception. Prolactin levels, however, may rise with use of oral contraceptives and thus should be monitored closely. If prolactin levels rise or amenorrhea persists, the woman should be referred for a gynecological and endocrinological evaluation.

Women with schizophrenia are at particular risk for pregnancy resulting from ineffective use of birth control and high rates of sexual assault. Even women with antipsychotic-induced amenorrhea may occasionally ovulate and thus can become pregnant. Teaching women with schizophrenia about methods for birth control and strategies for avoiding unwanted sexual advances is an important aspect of treatment. Women with schizophrenia who become pregnant are at increased risk for stillbirth, preterm delivery, and low-birth-weight babies, and their newborns are at increased risk for sudden infant death syndrome (

Bennedsen et al. 2001;

Nilsson et al. 2002; Jablonsky et al. 2005). Women with schizophrenia are also at increased risk for giving birth to an infant with cardiovascular congenital anomalies (Jablonsky et al. 2005). Although the reasons for these findings are not clear, research in obstetric clinics has found that pregnant women with schizophrenia typically attend fewer than 50% of prenatal care appointments (

Kelly et al. 1999), and inadequate prenatal care significantly increases the relative risk of preterm birth and postnatal death (

Vintzileos et al. 2002a,

2002b). Clinicians working with pregnant schizophrenia patients should strongly encourage them to obtain regular prenatal care in an effort to improve their birth outcomes.