The cluster C disorders are the most prevalent personality disorders in the general population (

1) (one of 10 individuals) and in outpatient clinic populations (

2) (more than one of two patients). Moreover, the presence of any cluster C personality disorder is invariably associated with poorer outcomes in the treatment of axis I disorders (

3–

5).

In light of these findings, it is puzzling to find such a paucity of controlled trials examining the effectiveness of individual psychotherapy in this population. Among the handful of studies that have been conducted, only one (

6) can be categorized as a randomized, controlled trial specifically designed to study the course of these disorders during and after treatment. In that study, 81 patients with predominantly cluster C disorders (70%) showed significant and equivalent improvement on measures of distress and social functioning after 40 sessions of two forms of dynamic psychotherapy. Furthermore, treated patients did significantly better than wait-list comparison subjects, and gains were maintained at 1.5-year follow-up. In two additional randomized, controlled trials, data for subgroups of patients with predominantly cluster C disorders were analyzed separately within larger trials designed to study major depression (

3,

4). The studies found that patients with personality disorders responded equally well to interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy (

3) and equally well to psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy and cognitive behavior therapy (

4). Finally, in one uncontrolled study, 38 patients with obsessive-compulsive and avoidant personality disorders treated with time-limited supportive-expressive therapy demonstrated significant average changes on diagnostic measures and on measures of distress, interpersonal problems, and personality functioning (

7).

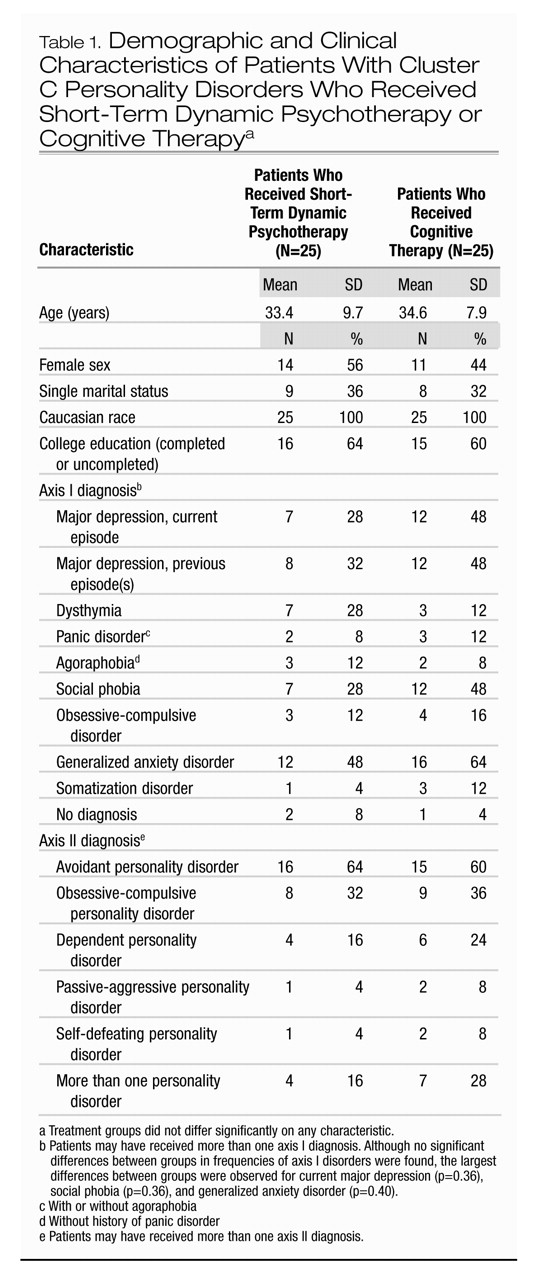

The present study extends the study by Winston et al. (

6) by examining the effects of 40-session, short-term dynamic psychotherapy specifically designed for personality problems (

8) and comparing those effects not with another form of dynamic therapy but with an alternative approach, that is, cognitive therapy. To our knowledge, this study provides the first empirical evidence of the effects of a form of cognitive therapy specifically intended for patients with personality dysfunction (

9). This study also takes notice of the suggestion of Perry et al. (

10) that the effects of specific therapies for specific personality disorders should be examined.

Discussion

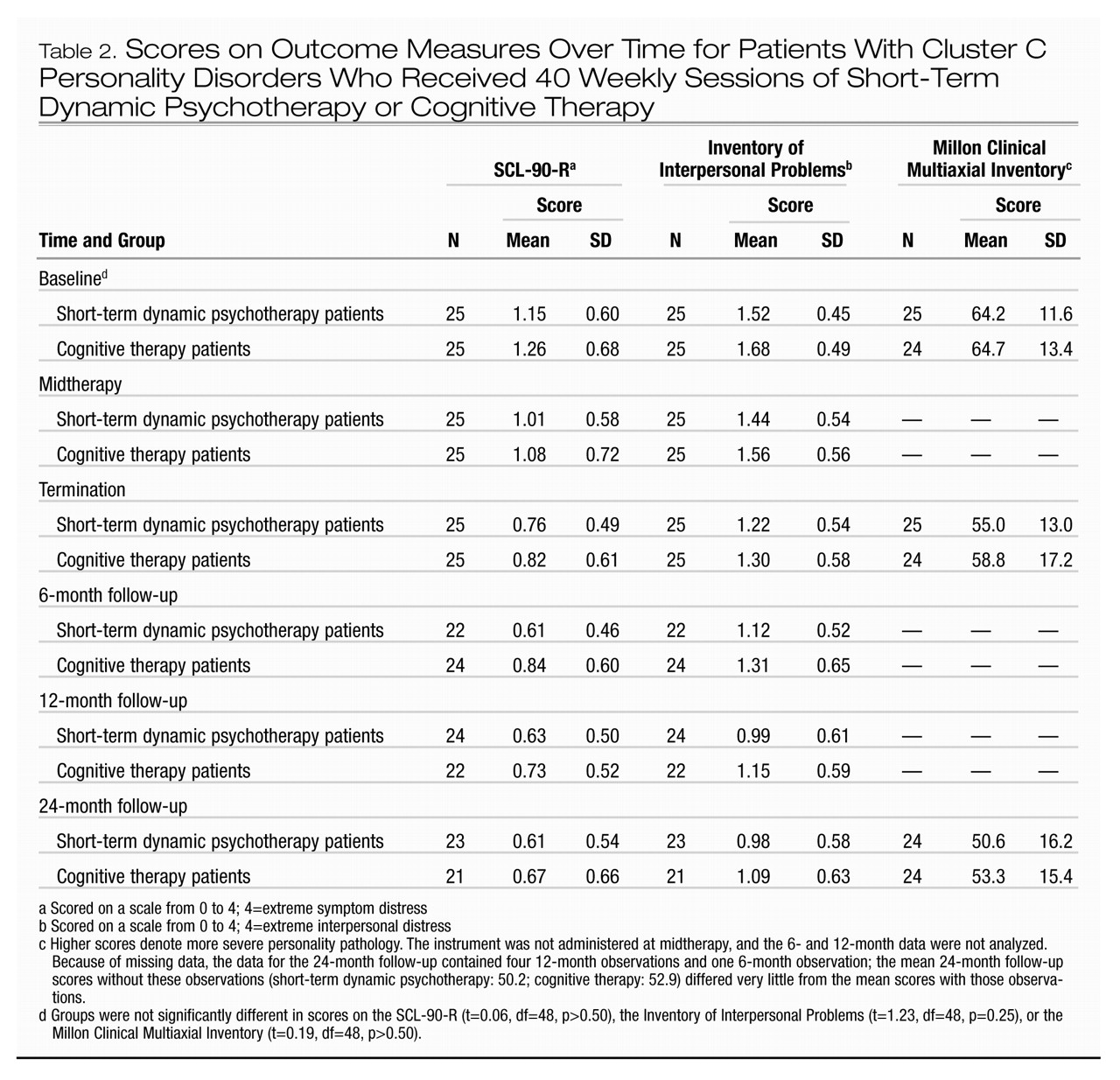

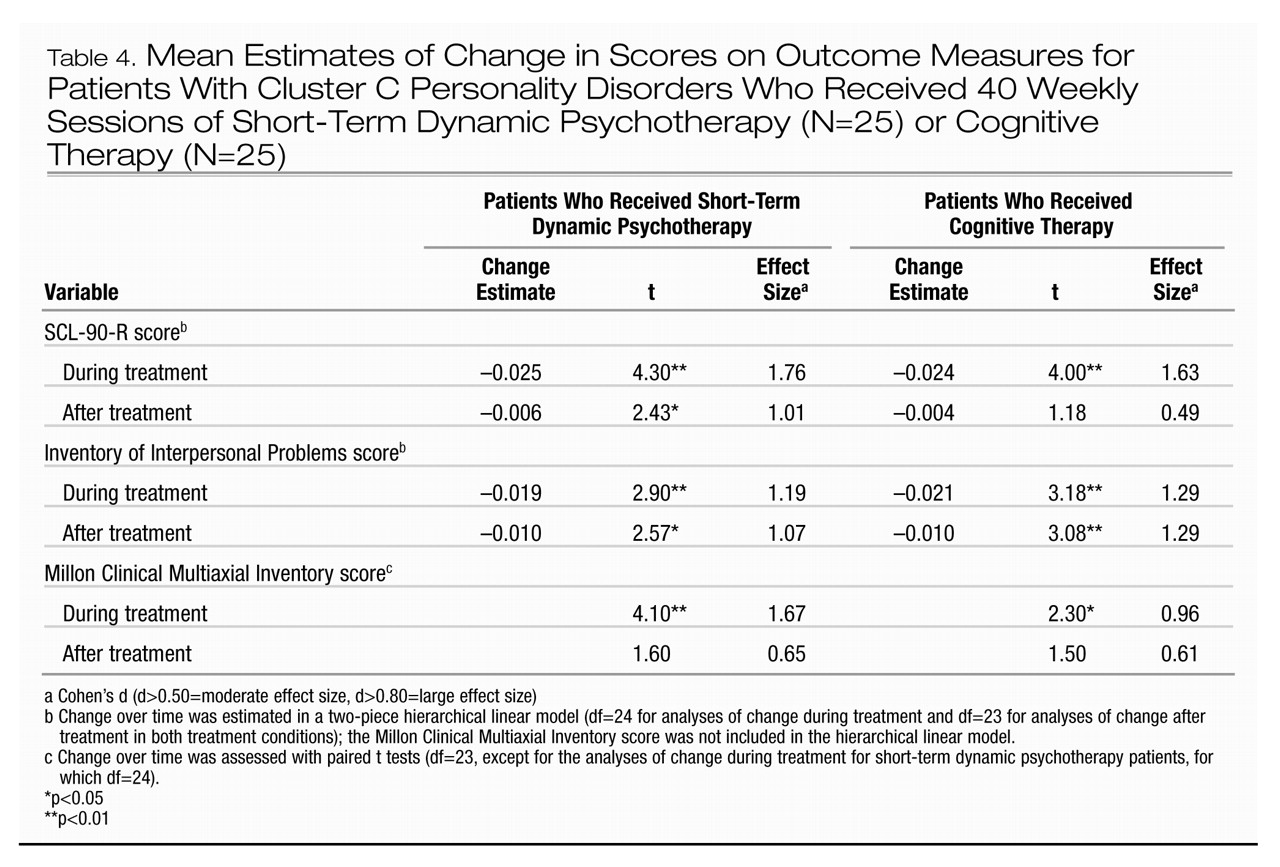

The large within-group effect sizes on all measures for short-term dynamic psychotherapy patients during treatment are in line with the findings of Winston et al. (

6). In fact, for the SCL-90-R, the measure that the two studies had in common, the effect size for short-term dynamic psychotherapy patients in the current study was three times higher than the effect size for the short-term dynamic psychotherapy patients in the study by Winston et al. (d=1.76, compared to d=0.59) and two times higher than the effect size for patients who received an alternative form of brief dynamic psychotherapy in the study by Winston et al. (d=1.76, compared to d=0.95).

Unlike the patients in many other psychotherapy outcome studies, the patients in this study on average continued to improve significantly after treatment. With respect to interpersonal problems, for instance, effect sizes for both treatments were large (short-term dynamic psychotherapy: d=1.07; cognitive therapy: d=1.29), and about 40% of the patients had recovered by 2 years after treatment. Similar recovery rates were found for core personality pathology. This finding of continued improvement supports one of the original justifications for short-term approaches articulated by short-term therapy pioneers such as Sifneos (

24). They argued that in successful short-term therapy, patients would, through an internalized therapeutic dialogue and other mechanisms, be able to achieve gains on their own after termination (

24).

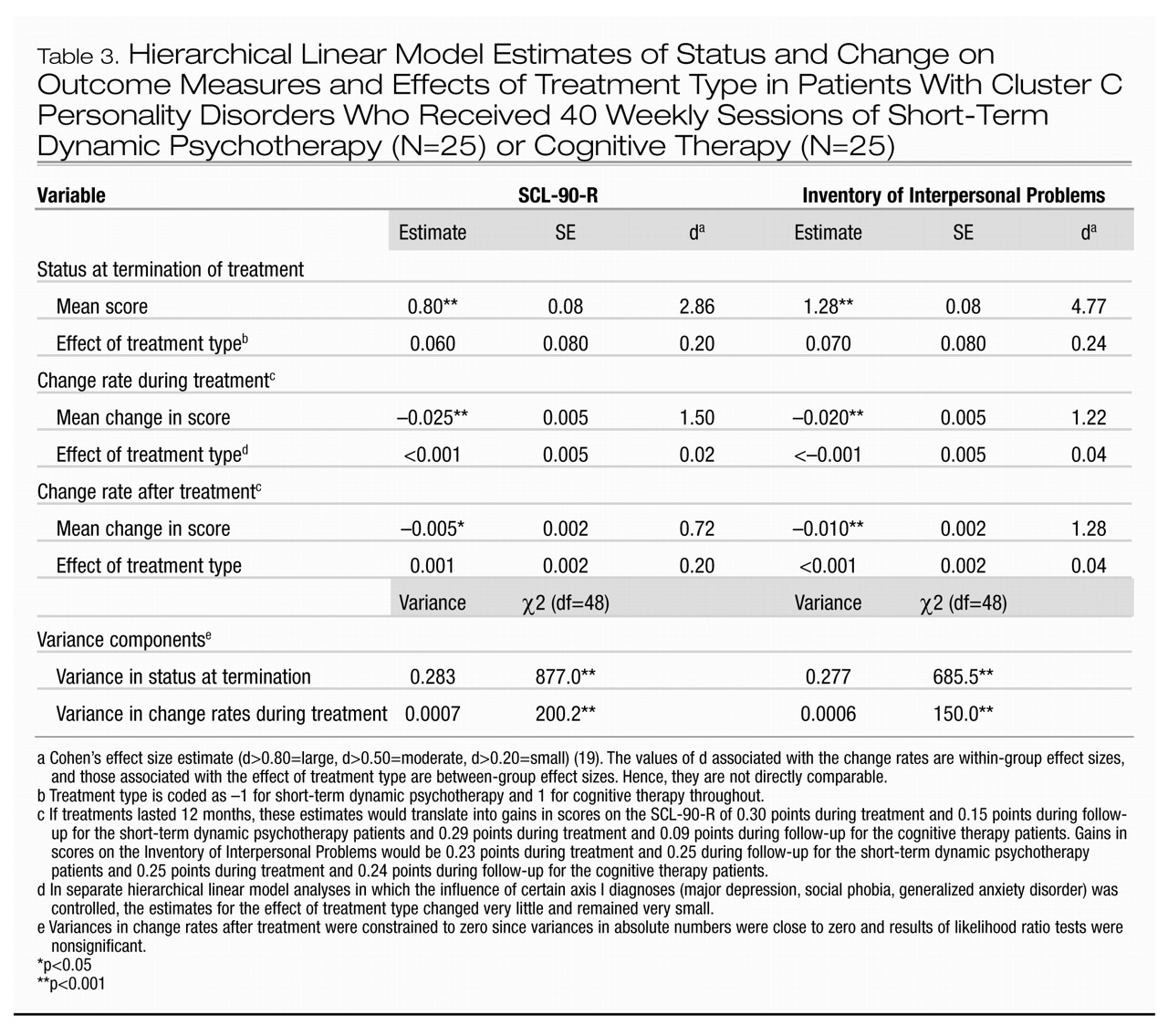

When the mean effects of the two treatments were contrasted, no statistically significant differences emerged for any of the measures during any of the time periods. As noted earlier, statistical power to detect medium-sized differences (see footnote a, Table 3, and reference

19) was insufficient, and, as a consequence, the risk of accepting a false no-difference result (i.e., a type II error) was increased. In such a situation there is reason to question whether the mean values observed on the measures in the two groups were truly equivalent. To cast more light on that suspicion, we conducted post hoc equivalency tests (

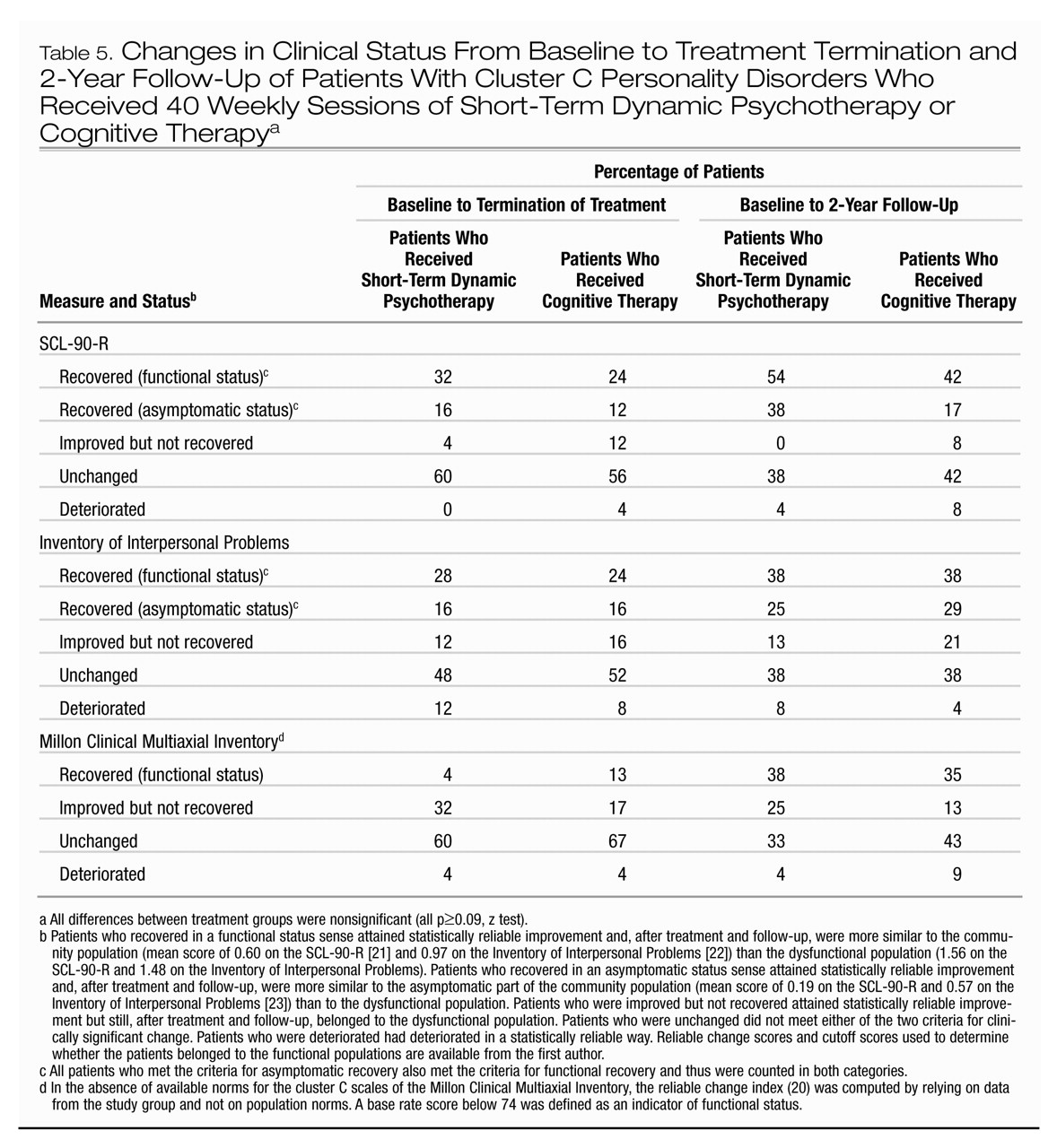

25) using the mean initial status and change rates (Table 3 and Table 4) for the outcome measures. The results showed that for the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory, but not for the SCL-90-R and Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, the difference between groups was small enough to declare the change rates equivalent (i.e., within an interval of ±20% around a zero difference). Thus, it can be concluded with some confidence that the small differences between groups with respect to change in core personality pathology during and after treatment are of trivial clinical importance. However, these test results do not allow us to make equally confident conclusions about the clinical unimportance of the differential treatment effects for symptom distress and interpersonal problems. In fact, the finding of the fairly large differences between groups in rates of clinically significant change as measured by the SCL-90-R (Table 5) lends credence to the conclusion that the differences in symptom distress between groups may be clinically important and nontrivial.

Although recovery rates generally tended to be greater when the 2-year follow-up period was also included in the analyses, this tendency was particularly strong, and in fact was statistically significant for the short-term dynamic psychotherapy patients, for outcomes measured with the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory. This result may be seen as a delayed effect of the treatments. As such, this finding supports the notion of Howard et al. (

26) that changes in life functioning, including personality functioning, are slower to occur than changes in subjective well-being and distress. This finding may also indicate that the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory captured different domains of psychopathology than did the SCL-90-R and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems.

Another limitation, in addition to the insufficient power to detect medium-sized effects, was the lack of observer-rated measures. As noted by Perry et al. (

10), it is a strength to include both observer-rated and self-report measures. To mitigate the initial reactivity of many self-report measures, Perry et al. recommended long-term follow-up when using such measures. We incorporated that recommendation and observed continuing strong effects on the measures after treatment. It is worth noting that Perry et al. found that self-report measures produce smaller effects than observer-rated ones. This finding may indicate that self-report measures tend to yield more conservative estimates of treatment effects in these patient populations.

We did not include a no-treatment comparison group due to ethical issues involved in withholding treatment in this population and because of the abundant evidence (

27) that psychotherapy in general is more effective than no therapy. Instead, for comparison groups, we used normative samples to assess the status of treated patients after treatment.

The findings of this study await replication in larger groups of patients and with different teams of therapists. In future studies it would be most important also to identify the characteristics of patients who do and do not have a response to treatment.