Several features of the Collaborative Research Program clinical trial design were considered advantageous for the study of the relation of patient predictors to treatment outcome. First, the multisite, common protocol design permitted study of a larger sample than do most single-site studies, but with uniformity of diagnosis and severity of depression across sites. Second, the extraordinary standardization of the therapies—with treatment manuals, therapist training, and monitoring of the quality of performance—would enhance the prediction of response to specific treatments by reducing the variability of the treatments themselves. Third, the use of a control condition, placebo with clinical management, would help differentiate predictors of response to specific treatments from predictors of general response or response to nonspecific treatment. Fourth, the use of standard outcome measures and response criteria would permit better comparison with the results of other studies. We examined predictors in two groups of patients: 1) those who completed the course of treatment, in order to search for predictors of outcome when there was full exposure to the specific ingredients of the therapies, and 2) all of those who entered the treatment trial, including those who withdrew before completion, in order to search for predictors of the full range of outcomes.

In previous single-site comparative treatment studies of interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy whose results would be most comparable to those of the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, some patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and tricyclic antidepressants were reported. Among the six studies that reported patient predictors of response to cognitive-behavior therapy, one (

11) found that pretreatment symptom severity was significantly associated with negative outcome at termination, while another (

12) reported an association with positive outcome. Inconsistent findings were reported for endogenous depression (

13,

14). Learned resourcefulness, assessed by the Self-Control Schedule, was found to be related to positive outcome (

11,

15). Cognitive dysfunction, as measured by the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale, predicted poor response at termination for group cognitive-behavior therapy (

16) and negative outcome at 1-year follow-up, though not at termination, for individual cognitive-behavior therapy (

17).

Method

A common protocol was conducted at three clinical research sites with a prospective, random-assignment, placebo-controlled design, double-blind for pharmacotherapy and with independent, blind clinical evaluation. A detailed description of the background and design of the main treatment study and the pilot training study has been previously published (

10).

The subjects were male and female outpatients between the ages of 21 and 60 years who met the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a current, definite episode of major depressive disorder on the basis of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (

20) structured interview and who had a score of 14 or more on the 17-item modified version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (

21) for at least 2 weeks before initial screening and again at rescreening after a 1- to 2-week wait or drug washout period. Exclusion criteria consisted of other specific psychiatric disorders, medical contraindications for the use of imipramine, concurrent psychiatric treatment, current active suicide potential, and need for immediate treatment. Patients were clinically referred, voluntary research subjects who gave written informed consent to participate.

All 28 therapists were experienced psychiatrists and psychologists who had received further clinical training by independent expert trainers and had met competence criteria in order to participate. Their performance was monitored throughout the study (

10,

22–

24). Treatments were conducted in accord with detailed manuals that specified the theoretical rationale, strategies, techniques, and boundaries of each modality (

25–

27). All treatments were planned to be 16 weeks in duration and to consist of 16–20 sessions. The pharmacotherapy dosage schedule was flexible, with a goal of 200 mg and a maximum of 300 mg. The clinical management component for the pharmacotherapy conditions provided not only guidelines for medication monitoring and management but also support, encouragement, and advice as necessary, although specific psychotherapy interventions were proscribed.

The total sample (N=239) comprised all patients who actually entered treatment from among the 250 patients who met inclusion criteria and were randomly assigned. The completer sample comprised only the patients who completed at least 12 sessions and 15 weeks of treatment and had clinical evaluations at termination. Clinical evaluations were available for 155 patients on the Hamilton depression scale for analyses of depression severity and for 156 patients for analyses of complete response (because of the inclusion of an additional patient for whom the Beck inventory score only was available). There were no statistically significant differences between treatments in overall attrition, treatment-related attrition, or symptomatic failure. Seven patients did not have termination evaluations (

1). The findings on comparative treatment efficacy with regard to depressive symptoms and general functioning, modality-specific measures of change, and the temporal course of treatment effect have been reported elsewhere (1, 2, and manuscript by J.T. Watkins et al., submitted for publication).

A comprehensive review of the literature was undertaken to identify patient predictors of response to cognitive-behavior therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and psychotherapy in general, as well as to tricyclic antidepressants and imipramine in particular. Among the predictor variables for which there was evidence of stability and replication, a limited set of independent variables for the multivariate analyses was selected on the basis of the distribution, intercorrelation, reliability, and face validity of the relevant measures. Personality disorders were added on the basis of experience in the pilot study. Because of the potential importance of a cognitive function predictor for cognitive-behavior therapy, the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale total score was selected on an exploratory basis. Two subsequent reports suggesting its relationship to outcome (see the beginning of this article) confirmed that decision.

The 26 independent variables were grouped within three domains: 1) sociodemographic variables-age, sex, marital status, social class; 2) diagnostic and course variables-endogenous, recurrent, primary, situational, and double depression, melancholia, family history of affective disorder, age at onset of first episode, duration of current episode, acuteness of onset of current episode, and number of previous episodes; and 3) function, personality, and symptom variables-social dysfunction, work dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, social satisfaction, expectation of improvement, number of personality disorders, dramatic personality disorder, odd personality disorder, anxiety, somatization/hypochondriasis, and interpersonal sensitivity.

The dependent measures of depression outcome at termination were 1) complete response, a stringent categorical measure based on the combination of a 17-item Hamilton depression scale score less than or equal to 6 and a Beck Depression Inventory (

28) score less than or equal to 9, and 2) depression severity, a continuous measure based on the 23-item Hamilton depression scale score, which included cognitive and atypical vegetative symptom items. Two dependent variables were selected to examine predictors of complete response or remission and change in the severity of depression, which would reflect partial response as well. One measure was based solely on clinical evaluator ratings, while the other also incorporated patient self-reports. Scores were based on ratings at termination of treatment for completers and on the last rating obtained for patients who were withdrawn or dropped out (generally, at either interim or early termination evaluation, but for 20 early dropouts, at rescreening evaluation). The interrater reliability, as assessed by intraclass correlation coefficients, for the Hamilton 17-item scale score ranged from 0.92 to 0.96 across sites and from 0.90 to 0.98 within sites; for the Hamilton 23-item scale score it ranged from 0.93 to 0.96 across sites and from 0.89 to 0.98 within sites. The Beck inventory total score showed good internal consistency, with an alpha coefficient equal to 0.78. The percentages of patients achieving complete response were 43.6% (N=68) and 31.4% (N=75) in the completer and total samples, respectively. The mean±SD depression severity scores at termination were 9.43±7.33 and 13.92±10.19 in the completer and total samples, respectively.

Data Analysis

To reduce further the number of independent patient variables from the initial set of 26 for the main predictor analyses across treatments, preliminary multiple regression analyses were conducted within each individual treatment condition, and only the most consistent predictors of outcome within individual treatments were selected for the main analyses. In both the total sample and the completer sample, initial analyses were conducted for independent variables in each of the three single domains, and then the “best” subsets of predictor variables within each domain were combined, with the pretreatment Hamilton depression score included, in final analyses conducted for each outcome measure. For these preliminary analyses we used the method of all possible subsets regression (

29), which examines all possible models containing the independent variables and selects the “best” subsets on the basis of an algorithm that uses the criterion of minimal Mallow’s C

p (

30) to select the regression model which minimizes the total mean squared error and bias. Each variable in the model contributed a minimum of 2% of the variance to the adjusted R

2 value and had a regression coefficient significant at p<0.10.

The subsets of predictor variables that emerged from these multiple regression analyses together constitute a model which best predicts outcome and are indicators of the relative likelihood of favorable or unfavorable outcome for each individual treatment. It should be emphasized, however, that the results do not identify the relative importance of any single variable, since the effect of each variable on outcome variance takes into account the partial effects of all of the other variables in the model. We recognize that, given the number of initial patient variables and the size of the groups in the individual treatment conditions, there is an increased risk of chance findings because of the inherent limitations of the regression analytic approach. We therefore consider these analyses exploratory in nature. While certain predictor relationships replicated earlier findings, other predictors will require further attempts to replicate.

The main data analyses examined the evidence for possible predictors of outcome across all treatments and of differential outcome among treatments. Only 13 variables were selected for these analyses, which were the most consistent predictors of outcome in the final regression analyses within individual treatments, having been predictors in at least two of the four analyses and at a level of significance of p<0.05 in at least one. For depression severity as a continuous measure of outcome, analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were performed, with treatment (four levels) and predictors (two or more levels) as factors in the design and with pretreatment depression severity and marital status as covariates. Marital status was included because it was significantly related to outcome and unevenly distributed among treatment conditions. For continuous predictor variables, patients were divided into two groups by using a median split in score. Significant main effects identified patient variables that predicted outcome across treatments. Significant Predictor by Treatment interactions identified differential treatment effects of patient variables on outcome. For complete response as a categorical measure of outcome, log linear analyses (Treatment by Predictor by Response) were performed, and the “best fit” models were examined for predictor main effects as well as Predictor by Treatment interactions. A significance level of p<0.10 was chosen for the overall difference among treatments. The Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used, so for any individual treatment comparison the obtained probability level had to be <0.017 to be considered significant at an adjusted alpha level of <0.10.

Discussion

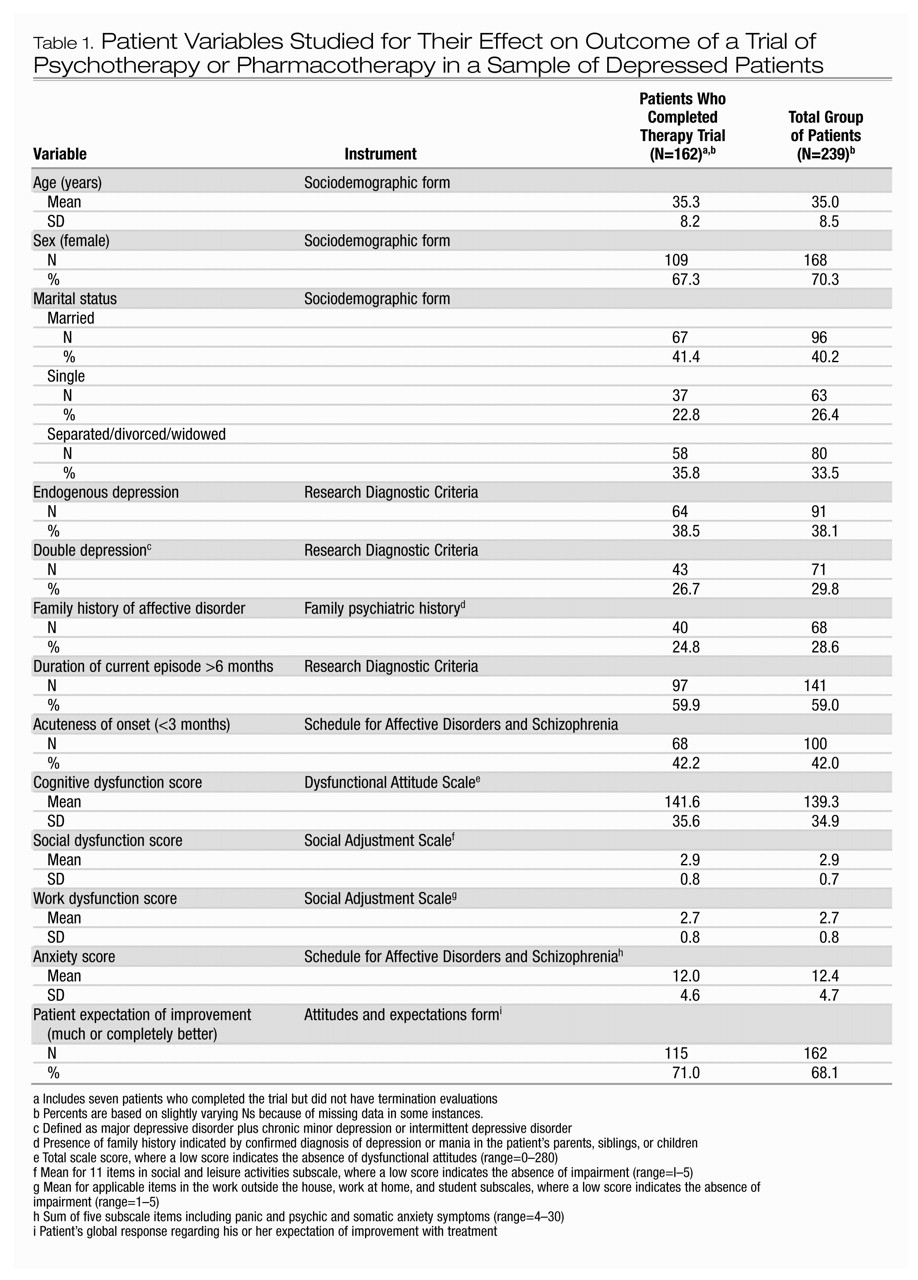

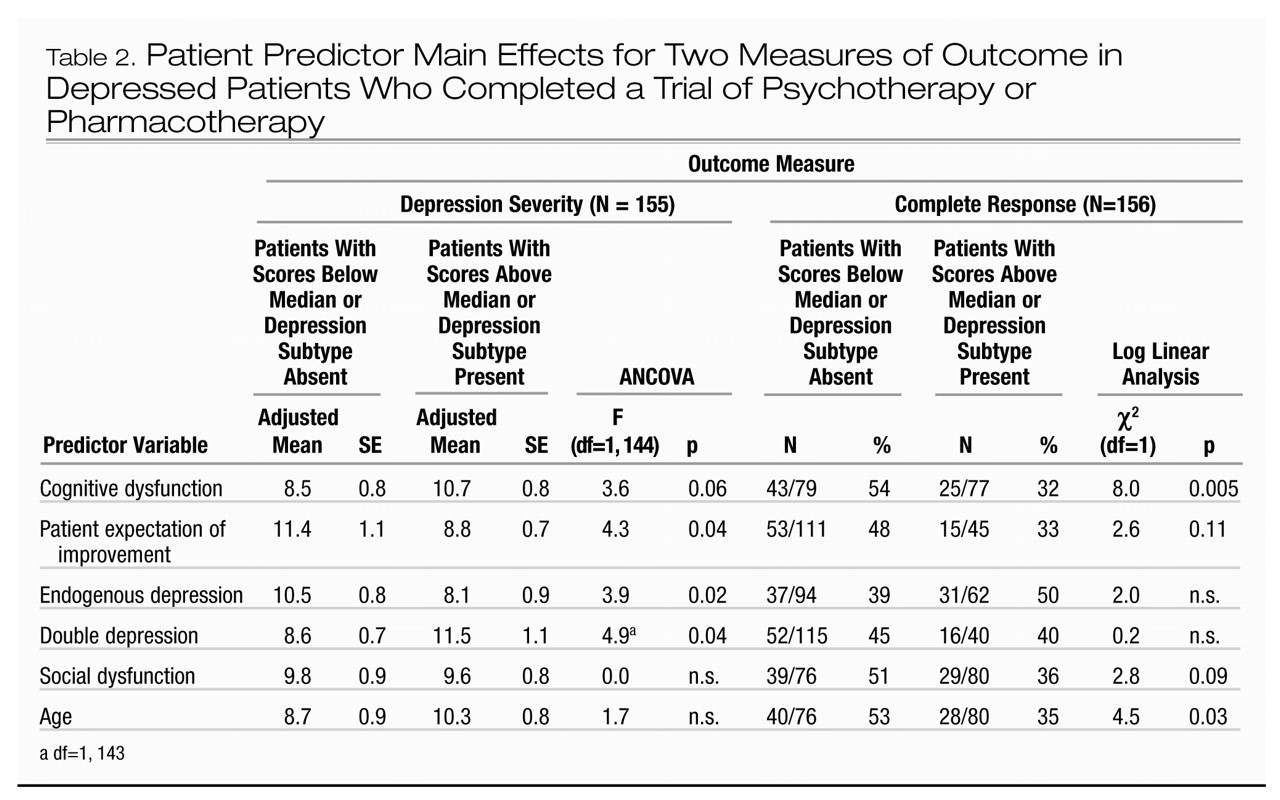

The results of this collaborative clinical treatment trial comparing the efficacy of two specific forms of psychotherapy with active and placebo pharmacotherapy demonstrate the relevance of patient characteristics for the prediction of outcome from an episode of major depressive disorder. Several characteristics of the depressive episode and patient functioning and cognition were indicators of overall prognosis without regard to the specific treatment received. These six patient predictors of depression severity or complete response were social dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, patient expectation of improvement, endogenous depression, double depression, and duration of current episode.

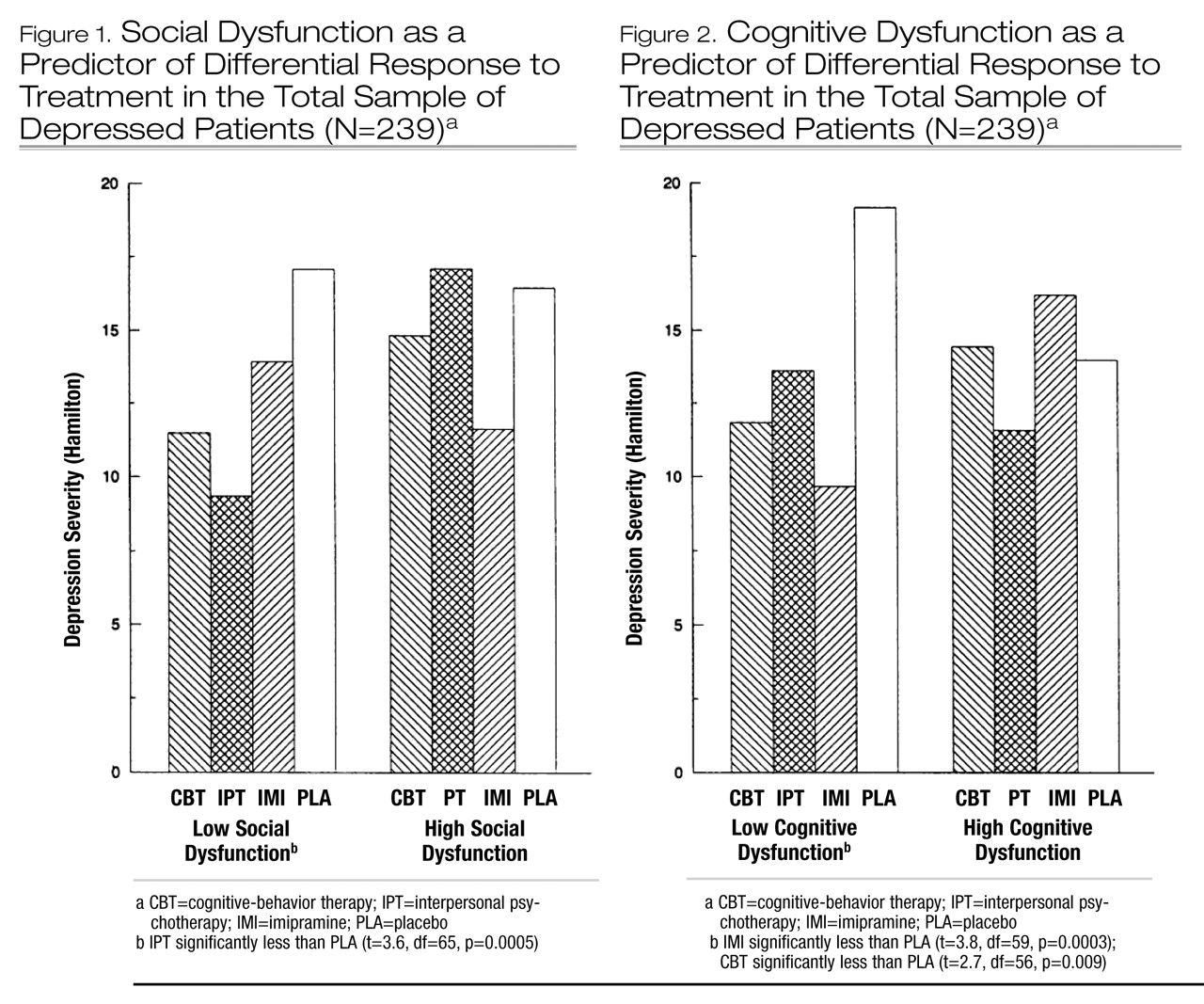

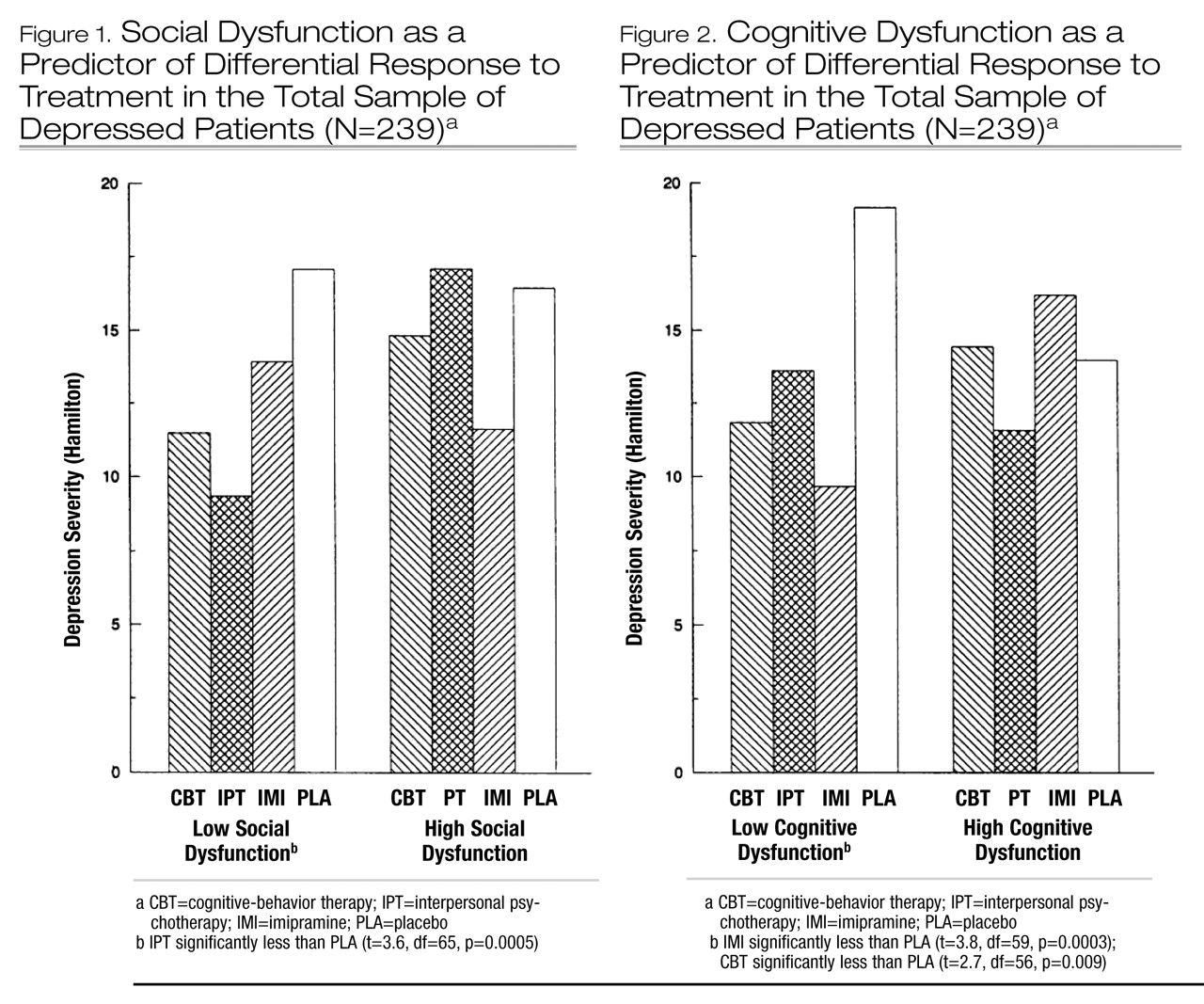

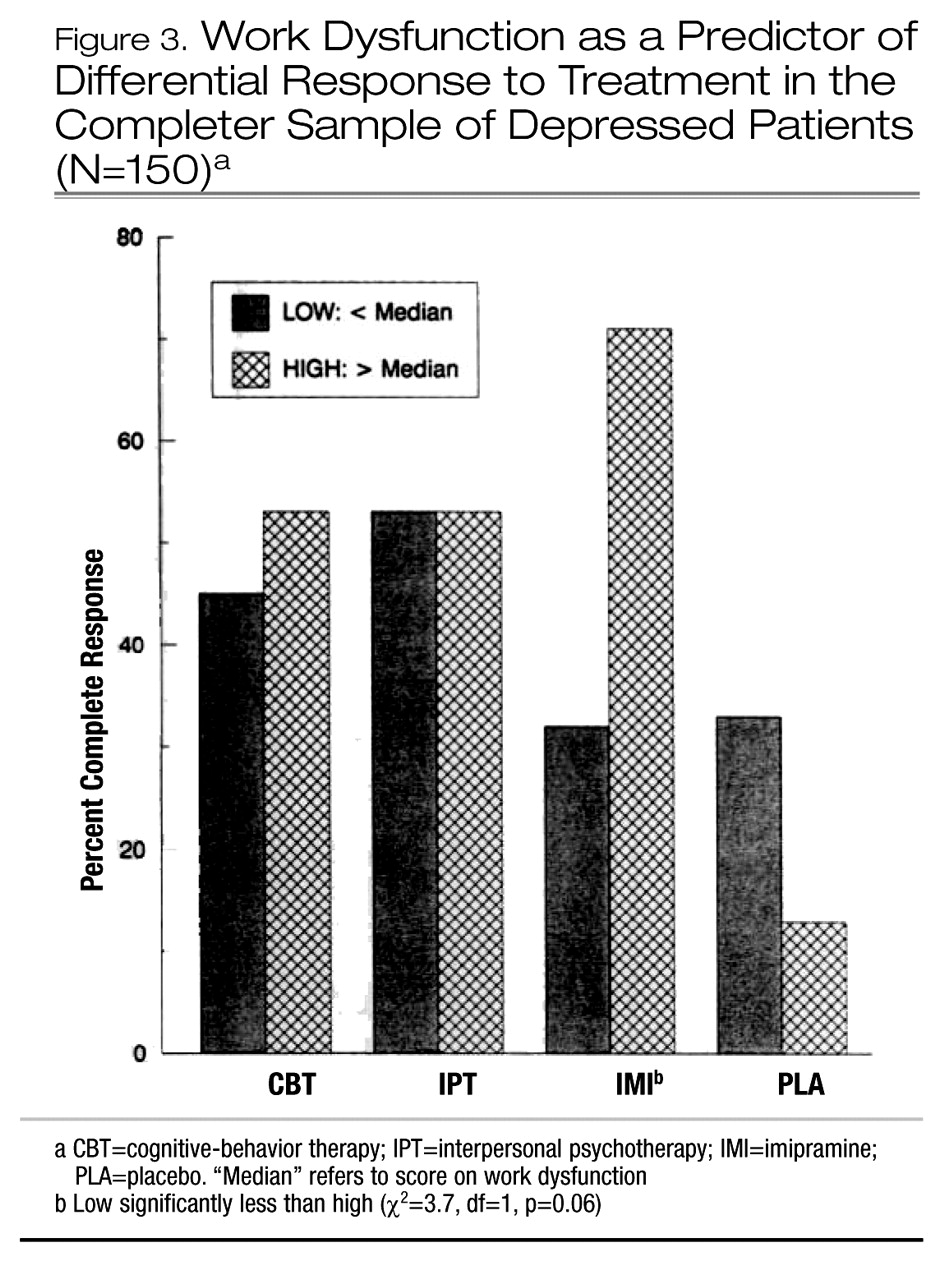

The results of these analyses also provide evidence for a limited number of characteristics of patient function that significantly predicted differential response to psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy with imipramine compared to placebo. There were no significant predictors of differential response among the three active treatments. Among patients with better initial social adjustment (e.g., low social dysfunction), those who received interpersonal psychotherapy became significantly less depressed than those who received placebo-CM and had a higher rate of complete response than those with high social dysfunction. Among patients with less perfectionistic and socially dependent attitudes (e.g., low cognitive dysfunction), those who received treatment with imipramine-CM or cognitive-behavior therapy became significantly less depressed than those who received placebo-CM, and those treated with imipramine-CM also had a higher rate of complete response than those with high cognitive dysfunction. Among patients with more impairment of function at work, school, or home (e.g., high work dysfunction), those who received imipramine-CM had a higher rate of complete response than those with low work dysfunction. The differential predictor effects of social and cognitive dysfunction were observed in the total sample only, which may have been because of 1) the larger size of the total sample, 2) the comparison with all placebo-treated patients rather than placebo completers only, or 3) the inclusion of the full range of outcomes, including attrition, thereby reflecting differential acceptability of the treatments, an important aspect of effectiveness. These differential patient predictors may also provide indirect evidence of the specificity of the treatments by identifying characteristics most responsive to those modalities.

We consider the findings that emerged from both the main analyses across treatments and the preliminary multiple regression analyses within individual treatment conditions exploratory in nature and in need of further replication. The main data analyses (ANCOVAs and log linear analyses) were based on 13 independent variables and 52 analyses (two dependent variables and two samples); with an alpha level of 0.10, approximately one predictor and five analyses would be expected to be significant by chance alone. Although eight variables were identified as significant predictors and there were 16 significant main effects and five interactions among the analyses, some findings (i.e., for age) may have been chance effects and may not be replicable. With the number of initial patient variables and the size of the samples within the preliminary individual treatment analyses, there is a greater risk of chance findings, considering the inherent limitations of the multiple regression analytic approach. Nevertheless, where the interesting patterns of predictors of response within individual treatment conditions are consistent with the results of the main analyses, we include them, with appropriate statistical caution, in the discussion. Given the historical difficulty of replicating predictors across studies, we have emphasized in our interpretation the consistent pattern of findings across samples and measures of outcome. We believe that the main results may be of both theoretical and clinical interest, particularly because of the uncommon effort to compare predictors of differential outcome with a placebo control.

Our finding that social dysfunction was a significant predictor of differential response to interpersonal psychotherapy is consistent with the finding from the individual treatment analyses that greater impairment in social function was associated with poorer response to interpersonal psychotherapy on measures of severity and recovery from depression. One previous study of interpersonal psychotherapy (

4) reported that good initial social adjustment predicted good outcome at termination for depressed patients, but only on measures of social function, not depression. Another psychotherapy study (

31) also reported that pretreatment social function predicted social function at termination. The finding that favorable response to interpersonal psychotherapy is associated not only with good social adjustment but with previous attainment of a marital relationship, higher satisfaction with social relationships in general, and heightened interpersonal sensitivity seems consistent with reports in the general psychotherapy literature that various indicators of social competence or achievement are associated with good psychotherapy response, whereas social impairment is not. Poor social skills and poor interpersonal relationships have been reported to be related to poor outcome of psychotherapy (

32,

33), while perceived social support, social satisfaction, and the ability to develop a good relationship have been associated with favorable response to psychotherapy (

31,

34–

38). However, this specific relation with pretreatment social adjustment was neither observed nor previously reported for patients treated with cognitive-behavior therapy, the other psychotherapy in our study. Thus, while the study shows that low social dysfunction predicts favorable general prognosis for outcome from depression, it also provides evidence of a specific responsiveness to interpersonal psychotherapy among those patients.

Less impairment in cognitive function as measured by the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale appears to be a general predictor of good prognosis as well as a specific predictor of good response to cognitive-behavior therapy (on depression severity) and imipramine-CM (on both outcome measures). In the two previous studies that examined the relation of dysfunctional attitudes to treatment response, high cognitive dysfunction was also associated with poor outcome at the termination of group cognitive-behavior therapy (

16) and poor outcome at 1-year follow-up after individual cognitive-behavior therapy (

17). Although in our study cognitive-behavior therapy appeared specifically to improve dysfunctional attitudes concerning the need for social approval (

2), there was a less favorable anti-depressant response to cognitive-behavior therapy in patients with greater cognitive dysfunction. This pattern of findings suggests that there may be an important distinction between the empirical effects of cognitive techniques in changing dysfunctional attitudes and a theory that links the presence of dysfunctional attitudes in depression to a preferential response to cognitive therapy.

To our knowledge, the relation of dysfunctional attitudes to outcome with other psychotherapies or pharmacotherapy has not been reported. The finding that in the total sample, low cognitive dysfunction predicted greater likelihood of complete response and greater improvement in depression severity for patients treated with imipramine-CM than for patients treated with placebo-CM was unanticipated. The better outcome of patients who expressed less socially dependent and perfectionistic attitudes may be consistent with the early reports that patients with neurotic (particularly, histrionic and labile) traits and with personality disorders respond poorly to tricyclic antidepressants (

7,

39–

42). Conversely, the differential predictor and individual treatment results suggest that patients with more socially dependent, dysfunctional attitudes may be more responsive to placebo treatment (

3). The possible relation of these attitudes to drug therapy compliance, tolerance of side effects, and acceptance of pharmacotherapy remains to be understood.

Cognitive dysfunction did not predict poor response to interpersonal psychotherapy in this study. Indeed, it appears that the least cognitively impaired patients responded more favorably to cognitive therapy, and the least socially impaired patients responded most favorably to interpersonal psychotherapy. One possible explanation for these results is that each psychotherapy relies on specific and different learning techniques to alleviate depression, and thus each may depend on an adequate capacity in the corresponding sphere of patient function to produce recovery with the use of that approach. Therefore, patients with good social function may be better able to take advantage of interpersonal strategies to recover from depression, while patients without severe dysfunctional attitudes may better utilize cognitive techniques to restore mood and behavior. Patients with more impairment in social or cognitive function might be further overwhelmed and demoralized by a treatment approach that requires reliance on those capacities to achieve improvement. Such patients might respond better to an alternative psychotherapy or combination treatment or require longer-term psychotherapeutic intervention.

Work dysfunction is a major aspect of overall social adjustment in depression, measuring impaired performance, subjective distress, and interpersonal function. Among patients who completed treatment with imipramine-CM, impairment of work function was a significant differential predictor of recovery, and the results on both outcome measures within the individual treatment analyses were consistent. On the contrary, in the few previous studies, social impairment, work disability, and poor employment history have been related to poor outcome with antidepressant medication (

39,

43). However, in our study imipramine-CM was previously reported (

1) to show consistent, significant superiority over placebo-CM on measures of recovery and symptomatic improvement among the more severely impaired and depressed patients, as defined by the Global Assessment Scale. Furthermore, we observed (manuscript by J.T. Watkins et al., submitted for publication) that imipramine-CM had a significant early advantage for improvement in global social adjustment at 4 weeks and 12 weeks of treatment among the more severely depressed patients. To the extent that impaired work function in depression may result from diminished interest, energy, initiative, and concentration, psychomotor retardation, and social withdrawal, preferential improvement with imipramine would be consistent with the recognized clinical effects of tricyclic antidepressants on these symptoms. This pattern of findings suggests that more severe depression, impairment, and work dysfunction are patient characteristics which are especially responsive to pharmacotherapy with imipramine and which may be of value in the selection of patients for this modality.

In this study endogenous depression was an overall predictor of lower depression severity at termination across all conditions. Previous studies, though, have reported that endogenous depression is a negative indicator of response to psychotherapy, both interpersonal psychotherapy (

18) and cognitive-behavior therapy (

13). However, Kovacs et al. (

14) found endogenous depression to be a positive predictor of outcome for patients who completed treatment with either a tricyclic antidepressant or cognitive-behavior therapy, while Blackburn et al. (

44) found no effect of endogenous features on response to either treatment. In our individual treatment analyses for interpersonal psychotherapy, endogenous depression predicted reduction of depression severity. This relationship was not observed for cognitive-behavior therapy. In the individual treatment analyses for imipramine-CM, our finding that endogenous depression was associated with complete response and depression severity corroborates the many previous reports that the endogenous subtype of depression is a major indicator of response to tricyclic antidepressants (

7,

14,

18,

19,

45). The lack of differential predictive effect for endogenous depression may be a result of measuring outcome after 4 months, since the differential effect of imipramine-CM on endogenous symptoms was most manifest at 8 and 12 weeks of treatment (manuscript by J.T. Watkins et al., submitted for publication). The reports of situational depression as a predictor of negative outcome for tricyclics and positive outcome for psychotherapy were not replicated, however.

The presence of double depression and the duration of the depressive episode are important aspects of the course of illness that appear to influence response to treatment. In a large naturalistic study uncontrolled for treatment, double depression was associated with favorable outcome from the major depressive episode only, but with poor outcome if outcome was defined as full recovery from the underlying chronic minor depression as well (

46–

48). In our controlled treatment trial, double depression was predictive of higher depression severity at termination but not of complete response, suggesting a relation to degree of improvement but not remission per se across all treatment conditions. Within the individual treatment analyses, double depression predicted lack of complete response from the episode among patients treated with placebo-CM but not among those who received one of the three active treatments. This may suggest that with active treatment, recovery from the major depressive episode is achieved as readily by patients with double depression as by those without chronic illness, but that more residual depressive symptoms persist among those with double depression. However, patients with double depression treated only by placebo-CM do not recover as readily. Results at follow-up should be most interesting, since previous studies have noted the greatest impact of double depression on subsequent course after recovery from the initial episode (

38,

48).

Longer duration of the current episode predicted higher depression severity and a lower rate of complete response in the total sample but not the completer sample, suggesting that the influence of chronicity on recovery was greater among patients who did not complete treatment, most notably in the placebo-CM condition. This finding is consistent with many previous studies that have reported a negative relation between duration of illness and clinical outcome of psychotherapy (

49–

52), imipramine and other tricyclic antidepressants (

34,

39,

53–

55), and placebo (

34,

56). Previous reports have indicated that acute onset of depression is a positive indicator of response to both tricyclic antidepressant treatment (

7,

9,

45) and psychotherapy (

33). In our study acute onset was associated with complete response among patients who completed imipramine treatment, and it predicted reduction in depression severity among patients treated with interpersonal psychotherapy, but only in the preliminary analyses within individual treatment conditions. Acute onset did not emerge as a significant predictor of differential treatment outcome in the main analyses. We therefore consider this to be only limited evidence supporting earlier findings.

Last, patients with higher expectation of improvement had a higher likelihood of recovery and lower level of depression severity across treatment conditions in both samples. Within individual treatment analyses, the negative influence of lower expectation of improvement appeared to occur among patients who received only placebo-CM or an incomplete course of imipramine (in the total sample only, not among completers of imipramine treatment). Low expectation of response to pharmacotherapy has been previously reported to predict attrition but not clinical outcome (

57). In the psychotherapy literature, the relation of patient expectations to outcome has been generally positive (

5,

6), consistent with these results. Other components of patient expectations and attitudes regarding treatment and depression remain to be explored. Since the pattern of findings for several patient predictors suggested a relation to outcome among patients who did not complete treatment, analyses of predictors of attrition are planned. Furthermore, the identification of potential patient predictors of long-term prognosis after initial treatment response will be of considerable clinical interest.