Most public and private sector addiction treatment providers face substantial pressure to treat large numbers of patients within a constrained budget. Yet, reducing services to meet budgetary requirements may pose a risk to addicted patients, many of whom are in an acutely vulnerable state when they enter treatment (e.g., homeless, suicidal, HIV-positive). This study evaluates one strategy for reconciling these conflicting pressures: making self-help group involvement a central goal of treatment, such that patients will rely relatively less on professional continuing care services over time but still attain good outcomes.

The first formal evaluations of the potential health care cost offset of various peer-directed interventions were conducted with seriously mentally ill individuals. What we believe was the first such study showed that discharged psychiatric inpatients randomly assigned to a patient-led support network were 50% less likely to be rehospitalized in the ensuing 10 months than were patients assigned to usual aftercare (

Gordon et al., 1979). Outpatient care needs were also reduced, with only 47.5% of experimental patients continuing to access community-based mental health services versus 74.0% of controls. This study did not report data on clinical outcomes, but later research on the 12-step self-help group GROW suggested that the organization reduces reliance on psychiatric care (

Kennedy, 1989) while simultaneously leading to improvement on self-rated and interviewer-rated measures of socio-psychologic functioning (

Roberts et al., 1999). Considered together, these findings raise the possibility that promoting self-help group involvement may yield cost savings without compromising outcomes.

One cannot assume, however, that sizable cost offsets will persist in the long term. In the

Walsh et al. (1991) randomized trial of alcohol-abusing blue collar workers, individuals initially assigned to AA-only no doubt had much lower costs in the first months of the study than did individuals assigned to AA+, hospital-based inpatient treatment program. But because the AA-only group experienced more relapses requiring medical intervention as the study progressed, by 2-year follow-up, the AA-only condition costs were only 10% lower than those of the AA+ Inpatient treatment condition. In the

Humphreys and Moos (1996) study, waning of offsets over time was also evident: the 3-year difference in cost was entirely attributable to the offset in the first year of the study. Whether cost offsets and good outcomes from self-help group involvement can be sustained are vital questions for the addiction field because of the ever-present temptation in both public and private budgeting to adopt practices that “save money” simply by shifting costs to later budgets.

DISCUSSION

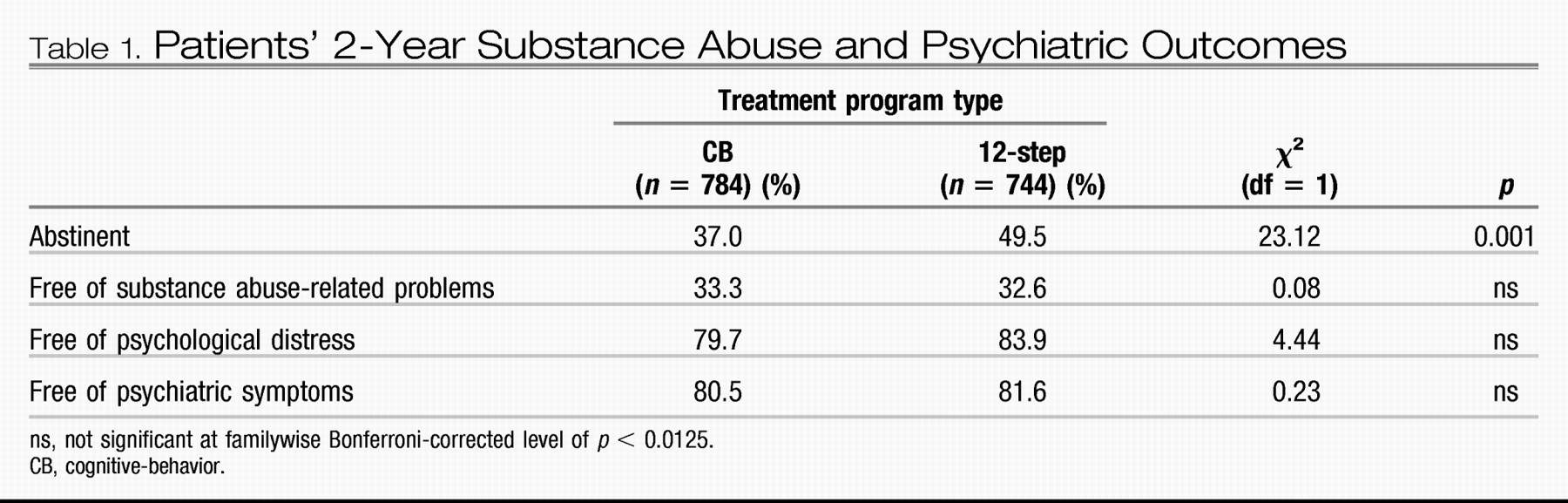

This quasi-experimental evaluation of patients entering two distinct forms of addiction treatment showed that the pattern of findings at 1 year largely persisted at 2 years. Both 12-step and CB program patients experienced substantial and comparable improvements in substance-related problems and psychiatric outcomes and required less ongoing professional treatment between 1 and 2 years than they had in the year after discharge. However, patients treated in 12-step treatment programs achieved substantially better abstinence rates (49.5 vs 37.5% in CB). This difference is actually slightly larger than that identified at 1-year follow-up (45.7% in 12-step vs 36.2% in CB,

Humphreys and Moos, 2001).

Group differences in help-seeking patterns were also similar to those found at 1 year. Not surprisingly, given the strong evidence 12-step treatment programs place on 12-step ideas and self-help group attendance, their patients attend meetings and talk to sponsors at substantially higher rates than do CB patients even 2 years after treatment. Although the size of the difference diminishes somewhat from the 1-year to the 2-year follow-up, 12-step patients also continue to use relatively less professional mental health services, increasing the savings associated with 12-step treatment over 2 years to an average of more than $8,000 per patient, in a sample of patients who had comparable mental health care utilization patterns before treatment. Because this figure does not include assessments of how the greater abstinence rate of 12-step patients may have reduced medical costs other than mental health services, increased employment rates, and lowered criminal justice costs, it likely represents a conservative estimate of the total savings to society produced by the active facilitation of posttreatment mutual help group involvement.

As mentioned, this study was not a randomized trial. Patients in each condition were not different at baseline on any measured variable, but this does not rule out the possibility that they differed on an unmeasured variable as would be ruled out (at least theoretically) in a randomized design. Our confidence in our results is therefore bolstered by the fact that randomized studies have also found that facilitation of 12-step mutual help group involvement promotes better outcomes (e.g.,

Timko et al., 2006), and that peer support approaches reduce health care costs of patients with addictive and psychiatric disorders (e.g.,

Galanter et al., 1987;

Gordon et al., 1979). Results such as those of this study suggesting a substantial improvement in outcomes that saves rather than costs money are welcome, even exciting, but we wish to make the following cautions against their overinterpretation.

First, the study must be understood in light of the impressive size of 12-step mutual help organizations in the United States. An addicted person can find an AA or NA meeting in virtually any city or town in the United States and at most hours of the day, which makes it more likely that 12-step treatment staff's efforts to promote group involvement will succeed. The causal chain analysis that we have conducted with this sample shows that this increased rate of 12-step mutual help involvement mediates the superior abstinence rate found after 12-step treatment versus CB treatment (

Humphreys et al., 1999). This does not mean that CB programs should convert to being 12-step oriented, but rather that they should either consider developing strategies for better linking their patients to 12-step groups (many emphases in CB programs have parallels in 12-step approaches; see

Finney et al., 1998) or starting CB-oriented self-help groups such as SMART Recovery, as are some treatment professionals in the United Kingdom. Because substance abuse patients are diverse, it would be incorrect to assume that all patients would have better outcomes and lower costs in 12-step than in other types of programs.

Second, it would be equally inaccurate to conclude from these results that because promoting self-help group involvement lowers the demand for continuing care, professional treatment services should be cut back and replaced with self-help groups. Every participant in this study received an intensive professional intervention, namely a 21-day to 28-day inpatient stay, and many afterwards received outpatient continuing care, which can work synergistically with posttreatment mutual help group involvement (

Ouimette et al., 1998). Therefore, the study's results contrast substantial professional treatment plus varying amounts of self-help group participation, rather than self-help groups only versus professional services only. As mentioned, the

Walsh et al. (1991) randomized trial indicates that inpatient treatment plus AA cannot be replaced by AA alone, as alcohol-abusing individuals in the former condition are less prone to relapse over time.

If the above would be the wrong conclusions, what would be the right ones? First, the national emphasis being placed by certain agencies (e.g., the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) on “recovery support services,” including self-help groups, is probably a cost-effective investment. Certain tasks supportive of recovery, such as providing encouragement, social activities, friendship, monitoring, and spiritual support, can probably be accomplished by peer-based services as well as they can by health care professionals, and at greatly reduced costs. This has a 2-fold benefit: greater likelihood of long-term recovery for the addicted individual and greater targeting of scarce professional resources to those patients who require such assistance.

In our experience, making the case that treatment programs should prioritize self-help group involvement can be difficult because many treatment providers believe they “do this already”; indeed, that every program does. In practice, however, what this often means is that at some point during treatment a counselor gives the patient a list of local self-help groups and suggests that the patient attend a meeting, which is a minimally effective clinical practice (

Sisson and Mallams, 1981). We therefore encourage treatment providers to use the more intensive methods of promoting self-help group involvement empirically demonstrated to be effective (see, e.g.,

McCrady et al., 1999;

Sisson and Mallams, 1981). The present study and a large number of other research projects (see

Humphreys, 2004, for a review) indicate that such efforts will maximize the maintenance of treatment gains. Even if the added costs of actively facilitating self-help group involvement cost several hundred dollars per patient, the results here indicate that such an investment would be an excellent use of fiscal resources.

In a time of reduced resources for addiction treatment in the United States, clinicians feel understandably stressed in their efforts to provide high-quality care under budget constraints. There is no magic bullet for this difficult situation, but the results presented here indicate that actively promoting self-help group involvement is a useful method for extending the benefits of treatment while lowering its ongoing cost.