Psychiatrists, like other medical professionals, are confronted by a need to maintain specialty specific knowledge despite an explosion in the amount of new information and the ongoing demands of clinical practice. Given these challenges, it is not surprising that researchers have consistently found gaps between actual care and recommended best-practices (

1–

10). In attempting to enhance the quality of delivered care, a number of approaches have been tried with varying degrees of success. Didactic approaches, including dissemination of written educational materials or practice guidelines, produce limited behavioral change (

11–

19). Embedding of patient-specific reminders into routine care can lead to benefits in specific quality measures (

11,

13–

16,

20–

23) but these improvements may be narrow in scope, limited to the period of intervention or unassociated with improved patient outcomes (

24–

27). Receiving feedback after self or peer-review of practice patterns may also produce some enhancements in care (

13–

15,

23,

28–

30). Given the limited effects of the above approaches when implemented alone, the diverse practice styles of physicians and the multiplicity of contexts in which care is delivered, a combination of quality improvement approaches may be needed to improve patient outcomes (

14,

19,

28,

29,

31–

34).

With these factors in mind, the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology are implementing multi-faceted Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Programs that include requirements for self-assessments of practice through reviewing the care of at least 5 patients (

35). As with the original impetus to create specialty board certification, the MOC programs are intended to enhance quality of patient care in addition to assessing and verifying the competence of medical practitioners over time (

36,

37). Although the MOC phase-in schedule will not require completion of a Performance in Practice (PIP) unit until 2014 (

35), individuals may wish to begin assessing their own practice patterns before that time. To facilitate such self-assessment related to the treatment of depression, this paper will discuss several approaches to reviewing one's clinical practice and will provide sample PIP tools that are based on recommendations of the American Psychiatric Association's Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder (

38).

Traditionally, most quality improvement programs have focused on retrospective assessments of practice at the level of organizations or departments (

39). The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures of the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) (

40) are a commonly used group of quality indicators that measure health organization performance. When used under such circumstances, quality indicators are typically expressed as a percentage that reflects the extent of adherence to a particular indicator. For example, in the quality of care measures for bipolar disorder (

41) derived from the American Psychiatric Association's 2002 Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Bipolar Disorder (

42), one of the indicators is that “Patients in an acute depressive episode of bipolar disorder who are treated with antidepressants, [are] also receiving an antimanic agent such as valproate or lithium.” In this example, to calculate the percentage of patients for whom the indicator is fulfilled, the numerator will be the “Number of patients in an acute depressive episode of bipolar disorder, who are receiving an antidepressant, and who are also receiving an anti-manic agent such as valproate or lithium.” and the denominator will be the “Number of patients in an acute depressive episode of bipolar disorder who are receiving an antidepressant” (

41).

As in the above example, most quality indicators are derived from evidence-based practice guidelines, which are intended to apply to typical patients in a population rather than being universally applicable to all patients with a particular disorder (

43,

44). In addition, practice guideline recommendations are mainly informed by data from randomized controlled trials. Patients in such trials may have significant differences from those seen in routine clinical practice (

45), including clinical presentation, preference for treatment, response to treatment, and presence of co-occurring psychiatric and general medical conditions (

43,

46,

47). These differences may result in treatment decisions for individual patients that are clinically appropriate but not concordant with practice guideline recommendations.

When quality indicators are used to compare individual physicians' practice patterns, quality measures can be influenced by practice size, patients' sociodemographic factors and illness severity as well as other practice-level and patient-level factors. For example, when small groups of patients are receiving care from an individual physician, a small shift in the number of individuals receiving a recommended intervention could lead to large shifts in the resulting rates of concordance with evidence-based care. Without appropriate application of case-mix adjustments, across-practice comparisons may result in erroneous conclusions about the quality of care being delivered (

48,

49). For patients with complex conditions or multiple disorders receiving simultaneous treatment, composite measures of overall treatment quality may yield more accurate appraisals than measurement of single quality indicators (

50–

52).

With the above caveats, however, use of retrospective quality indicators can be beneficial for individual physicians who wish to assess their own patterns of practice. If a physician's self-assessment identified aspects of care that frequently differed from key quality indicators, further examination of practice patterns would be helpful. Through self-assessment, the physician may determine that deviations from the quality indicators are justified, or he may acquire new knowledge and modify practice to improve quality. It is this sort of self-assessment and performance improvement efforts that the MOC PIP program is designed to foster.

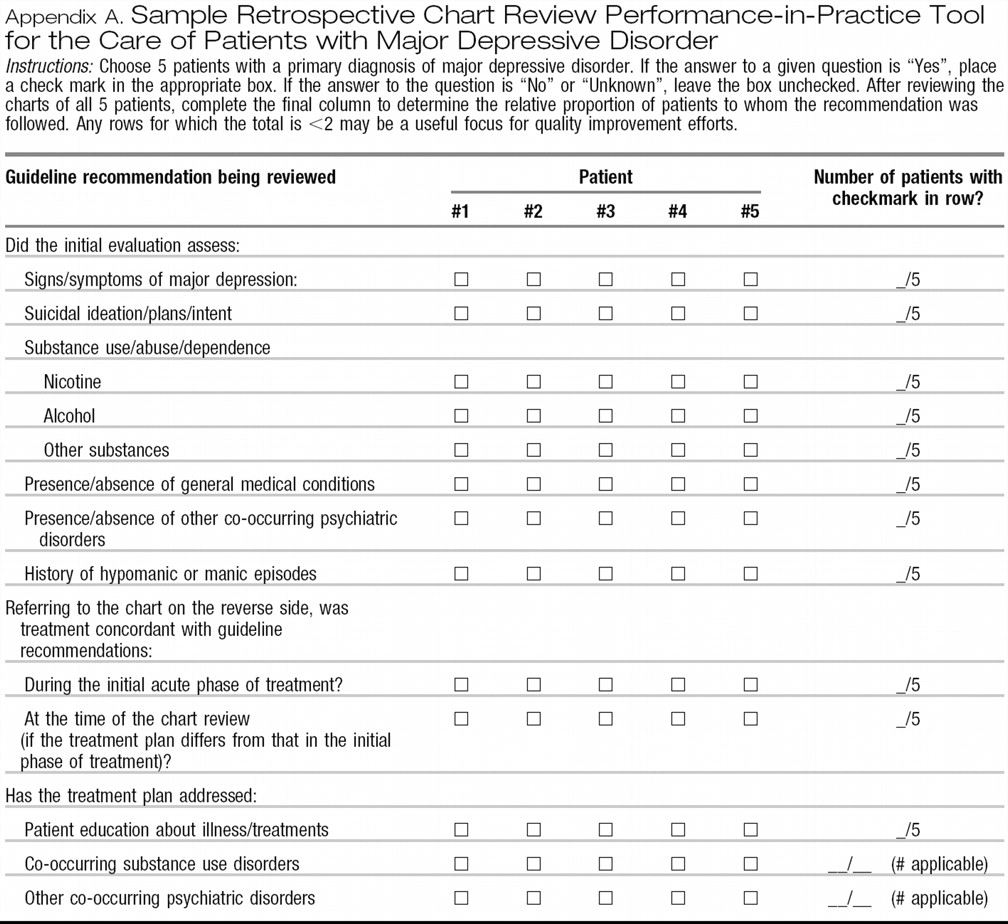

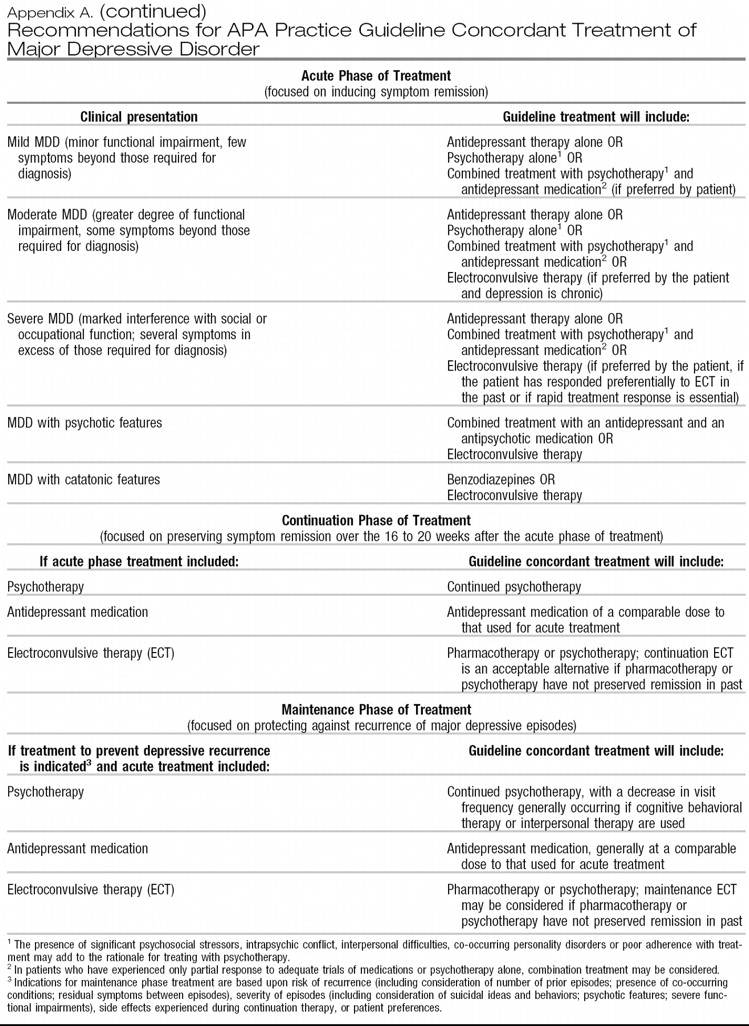

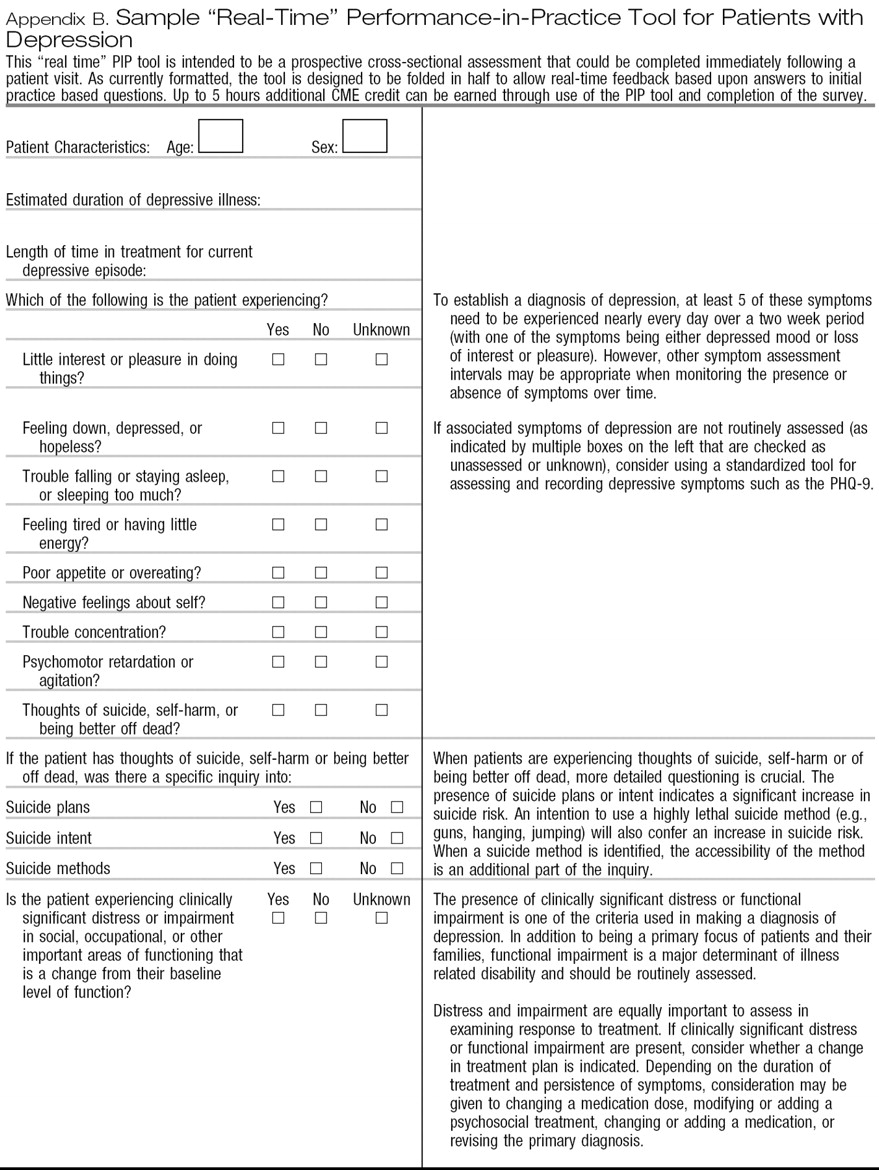

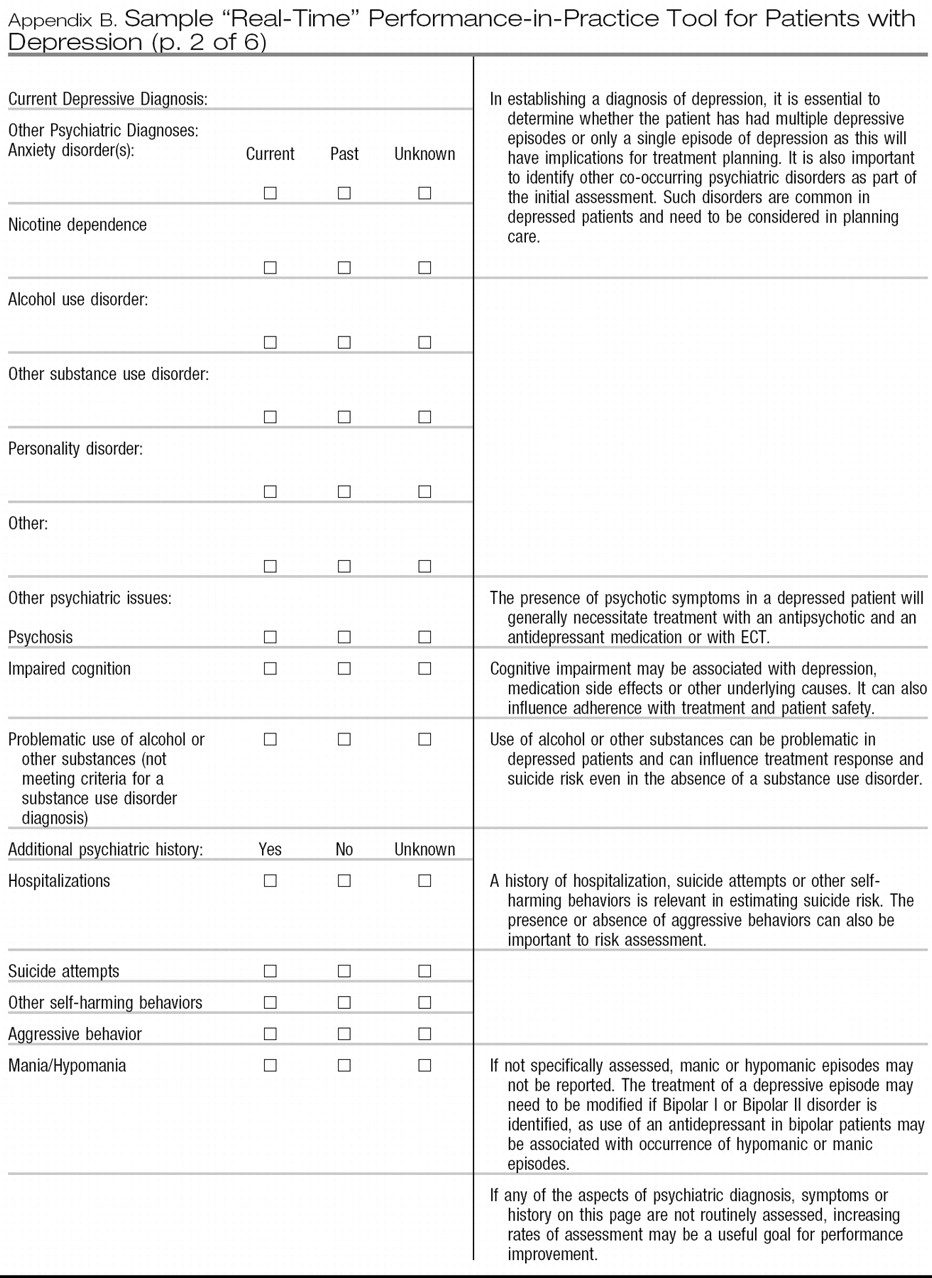

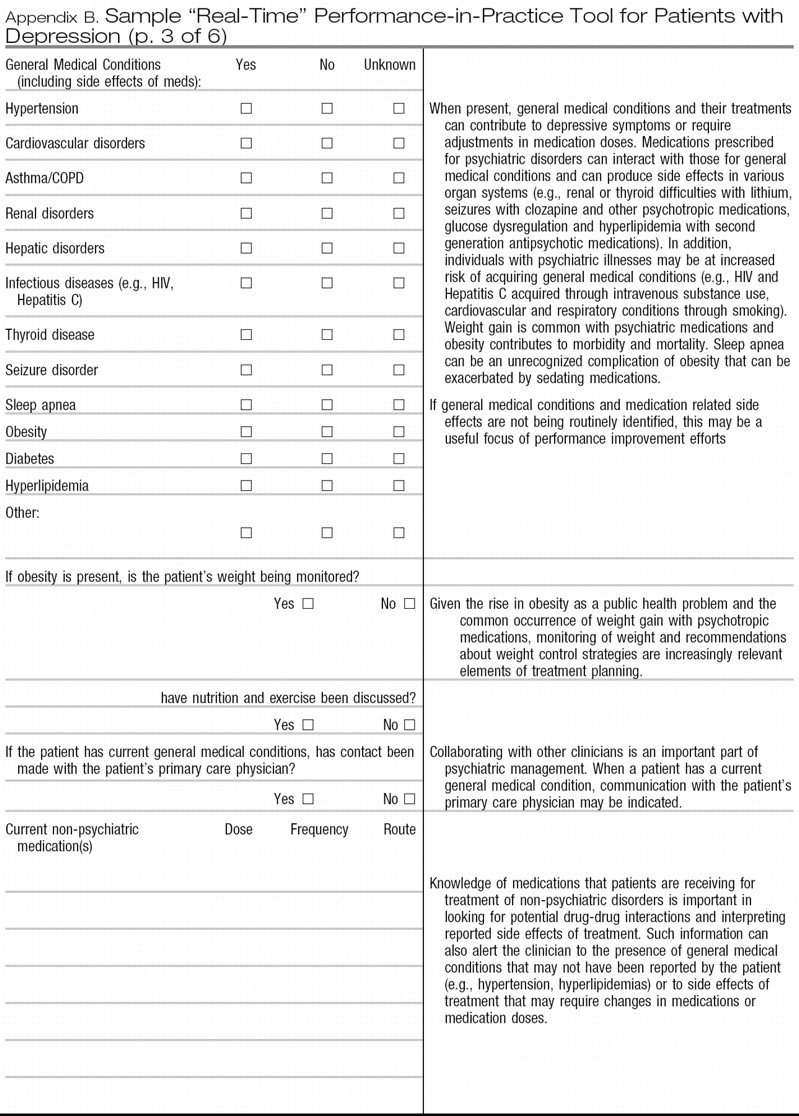

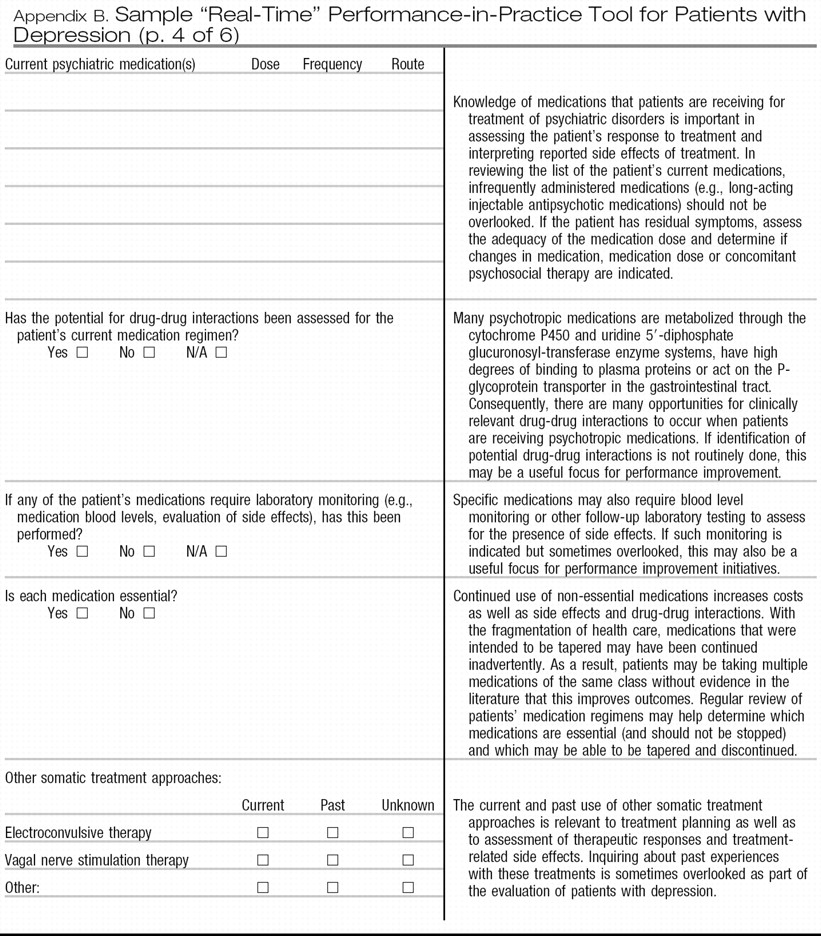

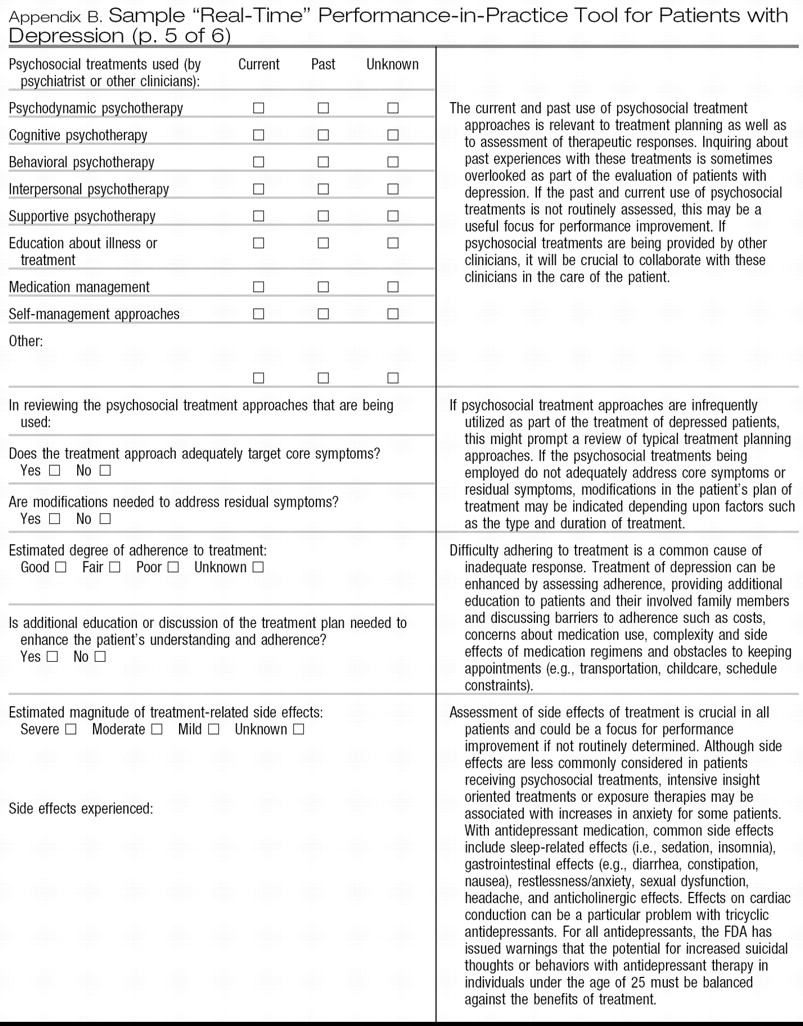

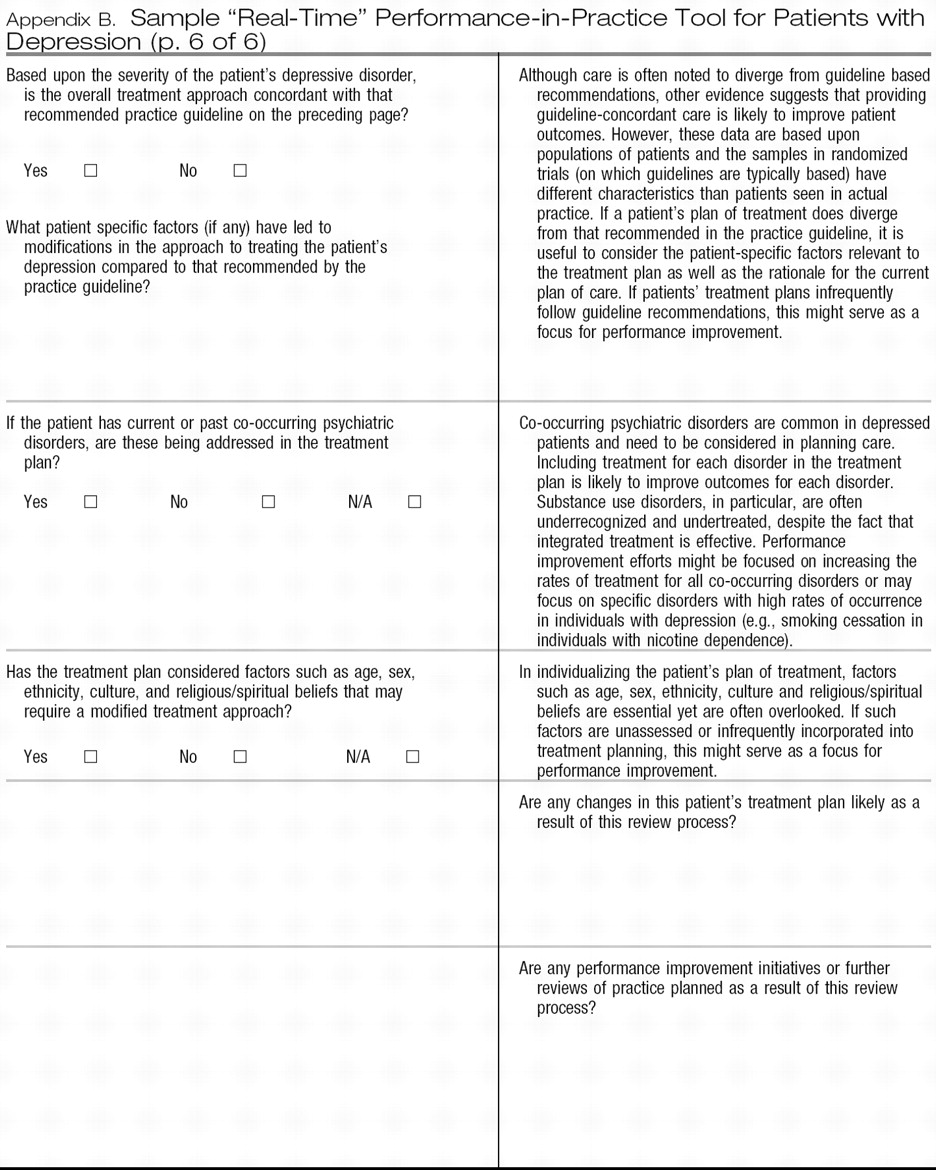

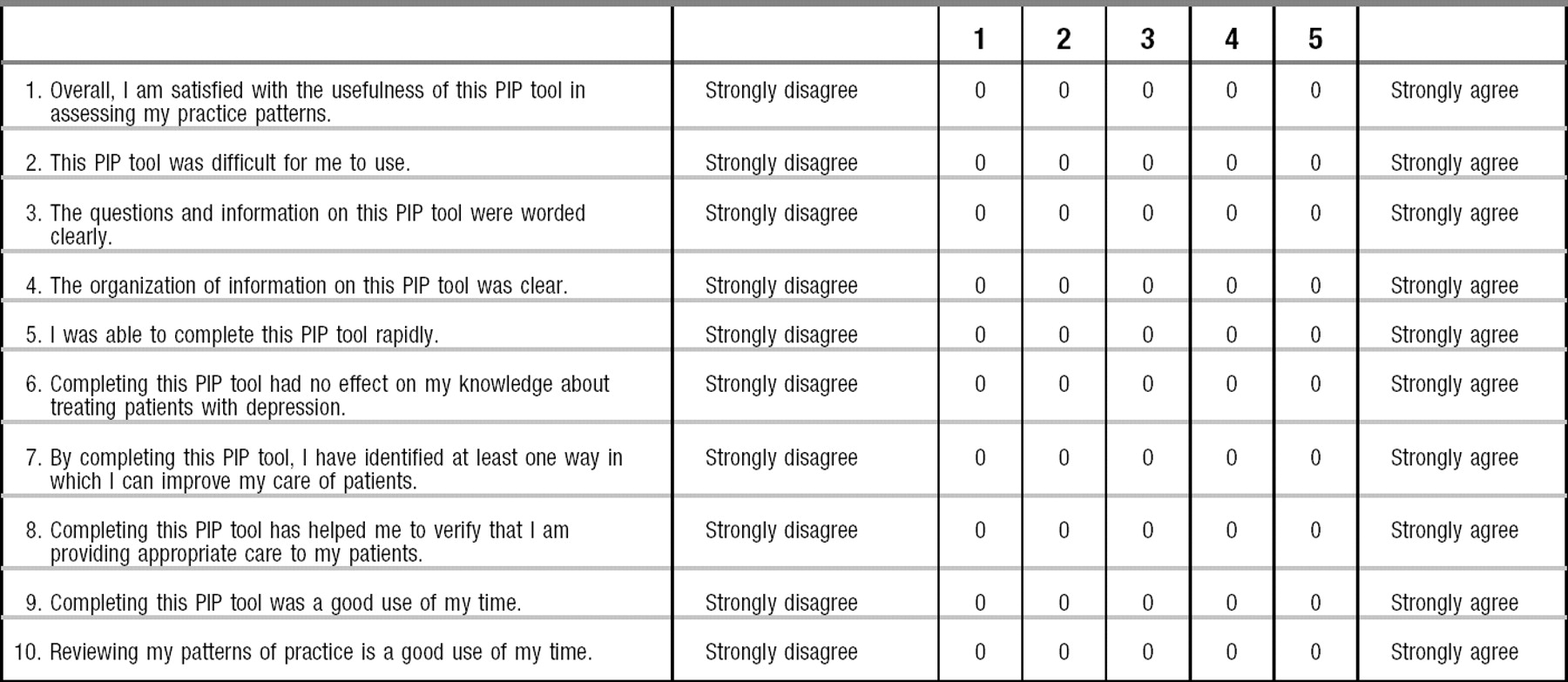

Appendices A and

B provide sample PIP tools, each of which is designed to be relevant across clinical settings (e.g., inpatient, outpatient), straightforward to complete and usable in a pen-and-paper format to aid adoption. Although the MOC program requires review of at least 5 patients as part of each PIP unit, it is important to note that larger samples will provide more accurate estimates of quality within a practice.

Appendix A provides a sample retrospective chart review PIP tool that assesses the care given to patients with major depressive disorder. Although it is designed as a self-assessment tool, this form could also be used for retrospective peer-review initiatives. As with other retrospective chart review tools, some questions on the form relate to the initial assessment and treatment of the patient whereas other questions relate to subsequent care.

Appendix B provides a prospective review form that is intended to be a cross-sectional assessment and could be completed immediately following a patient visit. As currently formatted,

Appendix B is designed to be folded in half to allow real-time feedback based upon answers to the initial practice-based questions. This approach is more typical of clinical decision support systems that provide real-time feedback on the concordance between guideline recommendations and the individual patient's care. In the future, the same data recording and feedback steps could be implemented via a web-based or electronic record system enhancing integration into clinical workflow (

53). This will make it more likely that psychiatrists will see the feedback as interactive, targeted to their needs and clinically relevant. Rather than relying on more global changes in practice patterns to enhance individual patients' care, such feedback also provides the opportunity to adjust the treatment plan of an individual patient to improve patient-specific outcomes (

54–

56). However, data from this form could also be used in aggregate to plan and implement broader quality improvement initiatives. For example, if self-assessment using the sample tools suggests that signs and symptoms of depression are inconsistently assessed, consistent use of more formal rating scales such as the PHQ-9 (

57–

59) could be considered.

Each of the sample tools attempts to highlight aspects of care that have significant public health implications (e.g., suicide, obesity, use of tobacco and other substances) or for which gaps in guideline adherence are common. Examples include underdetection and undertreatment of co-occuring substance use disorders (

5) and the relatively low concordance with practice guideline recommendations for use of psychosocial therapies and for treatment of psychotic features with MDD (

4).

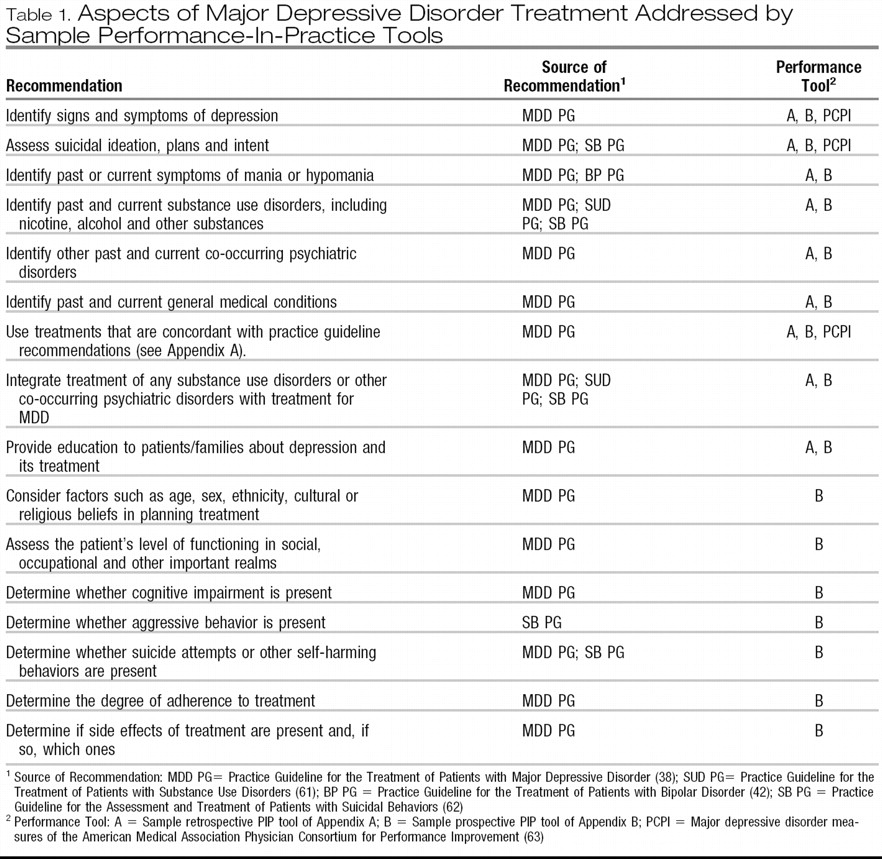

Table 1 summarizes specific aspects of care that are measured by these sample PIP tools. Quality improvement suggestions that arise from completion of these sample tools are intended to be within the control of individual psychiatrists rather than dependent upon other health care system resources.

After using one of the sample PIP tools to assess the pattern of care given to a group of 5 or more patients with major depressive disorder, the psychiatrist should determine whether specific aspects of care need to be improved. For example, if the presence or absence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders has not been assessed or if these disorders are present but not addressed in the treatment plan, then a possible area for improvement would involve greater consideration of co-occurring psychiatric disorders, which are common in patients with MDD.

These sample PIP tools can also serve as a foundation for more elaborate approaches to improving psychiatric practice as part of the MOC program. If systems are developed so that practice-related data can be entered electronically (either as part of an electronic health record or as an independent web-based application), algorithms can suggest areas for possible improvement using specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-limited objectives (

60). Such electronic systems could also provide links to journal or textbook materials, clinical practice guidelines, patient educational materials, drug-drug interaction checking, evidence based tool kits or other clinical materials. In addition, future work will focus on developing more standardized approaches to integrating patient and peer feedback with personal performance review, developing and implementing programs of performance improvements and reassessment of performance and patient outcomes.