Even before Hurricane Katrina struck in late August 2005, people in the U.S. Gulf Coast were among the sickest, poorest, and most underserved in the country (

1). Their burdens were severely compounded by the subsequent devastation and displacements experienced by 1.5 million inhabitants in an area the size of Great Britain (

2,

3). More than $100 billion in federal aid has already been allocated or requested, much of it initially focused on addressing immediate needs for shelter, food, injuries, and other acute medical conditions (

4–

11).

Treatment needs of the many Katrina survivors with mental disorders have received far less attention, despite the fact that the widespread experience of trauma may have precipitated many new cases and exacerbated preexisting mental disorders (

12). Entire delivery systems were destroyed, and people with mental disorders may have been unable to overcome the formidable financial, structural, and other barriers to obtaining care (

13). Attitudinal barriers and competing demands may have prevented even those with access from obtaining effective treatments (

14,

15).

The aims of the study presented here were to describe the mental health services used by respondents to a geographically representative survey of displaced and nondisplaced Katrina survivors. We examined the system sectors and treatment modalities used as well as the intensity and continuity of treatments. We also identified correlates and reasons for undertreatment to help ensure that future relief efforts will meet the needs of survivors with mental illness.

RESULTS

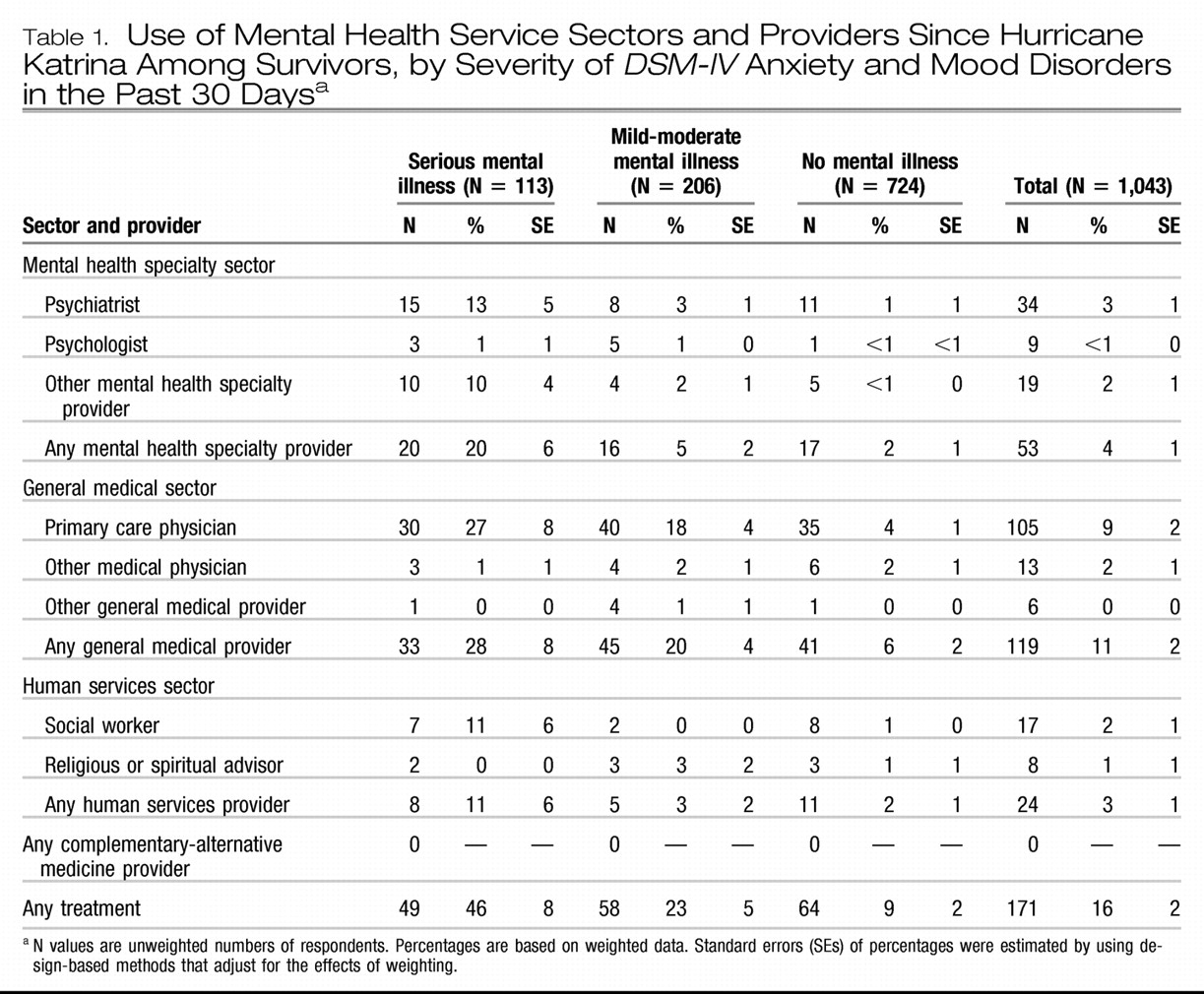

USE OF SERVICES BY SEVERITY OF ILLNESS

As reported in a previous publication from this study (

12), 31% of CAG respondents were estimated to meet criteria for a

DSM-IV mood or anxiety disorder in the 30 days before interview; 11% of respondents were classified as having a seriously impairing mood or anxiety disorder and 20% as having a mild-moderate mood or anxiety disorder. As

Table 1 shows, 16% of respondents used mental health services since the disaster, including 46% of those with serious anxiety or mood disorders in the past 30 days and 23% with mild-moderate anxiety or mood disorders in the past 30 days (32% of those with either serious or mild-moderate disorders [results not shown but available on request]), and 9% of those with no disorders of these types. Among all respondents, the general medical sector was used most commonly. Overall, 11% of respondents received services in the general medical sector, followed by the mental health specialty sector (4% of respondents), and the human services sector (3%). No respondents reported use of the complementary-alternative medicine sector. This pattern of sector use was evident in all groups defined by severity of disorder.

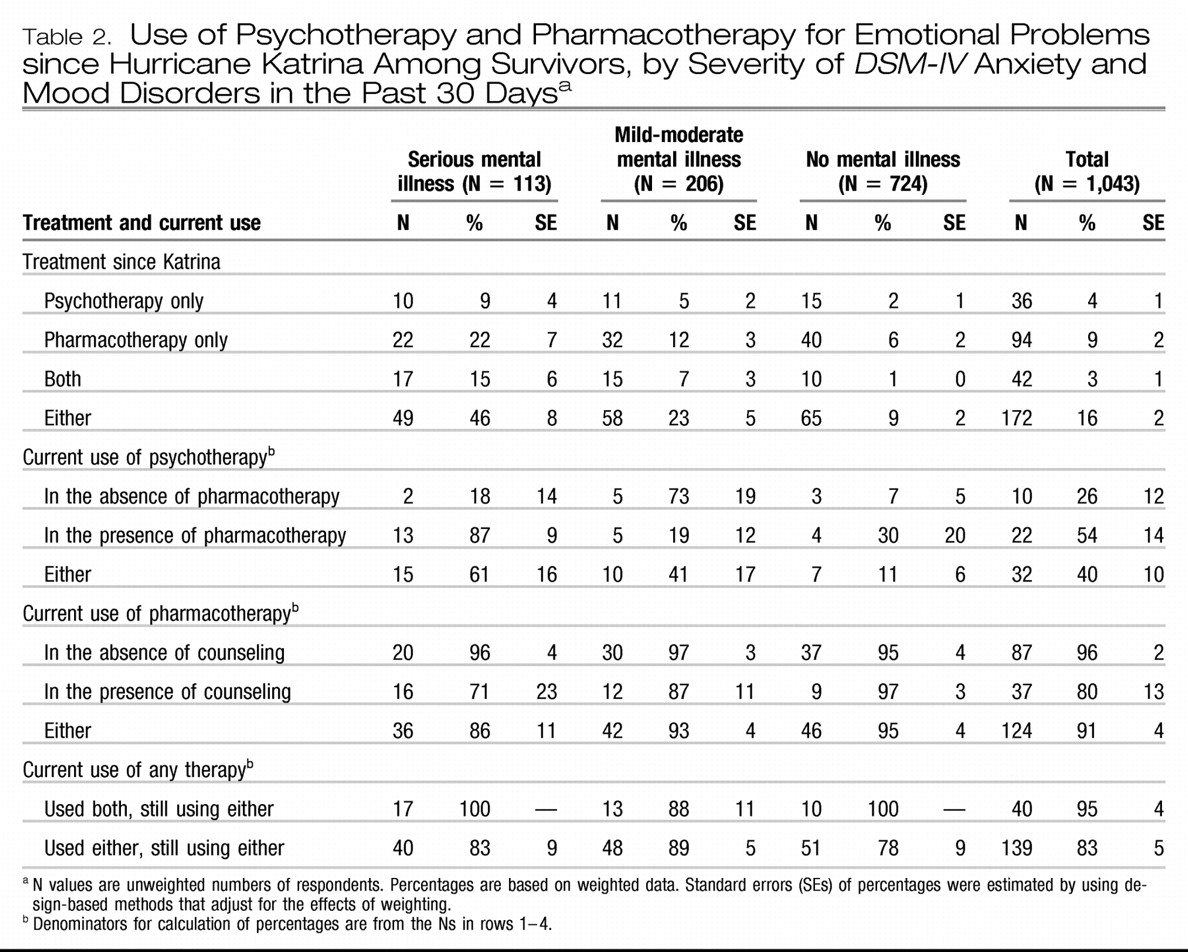

USE OF PSYCHOTHERAPY AND PHARMACOTHERAPY

As shown in

Table 2, the most common treatment was pharmacotherapy alone (used by 9% of respondents), followed by psychotherapy alone (4%), and pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy (3%). The relationships between disorder severity and use of these treatments were generally monotonic. Combined pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy was the second most commonly used treatment among respondents with serious disorders, whereas it was the least common among respondents without serious or mild-moderate disorders.

Among respondents who received treatment since the disaster, only a minority were still receiving psychotherapy at the time of the interview. On the other hand, the vast majority of those treated since the disaster were still receiving pharmacotherapy. Continuing use of any treatment at the time of the interview was more common among those who had ever used combined-modality treatment than among those who had used a single modality only (95% compared with 83%).

TYPES OF PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS

The most frequently used specific classes of psychotropic medication were antidepressants (used by 91 respondents, or 60% of those using any type of psychotropic medication), followed by benzodiazepines (43 respondents, or 30%), mood stabilizers (five respondents, or 6%), nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (14 respondents, or 5%), and antipsychotics (six respondents, or 3%). (More detailed results are available at hurricanekatrina. med.harvard.edu/publications.php.) Generally monotonic relationships between disorder severity and use of individual drug classes existed only for antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics.

NUMBER AND DURATION OF PSYCHOTHERAPY VISITS

Although 59 of the 78 psychotherapy users had visits that typically lasted for 30 minutes or more, 19 did not. Likewise, the number of psychotherapy visits obtained since the disaster was low; only 11 respondents (9%) received eight or more visits, and 46 (64%) received one or two visits.

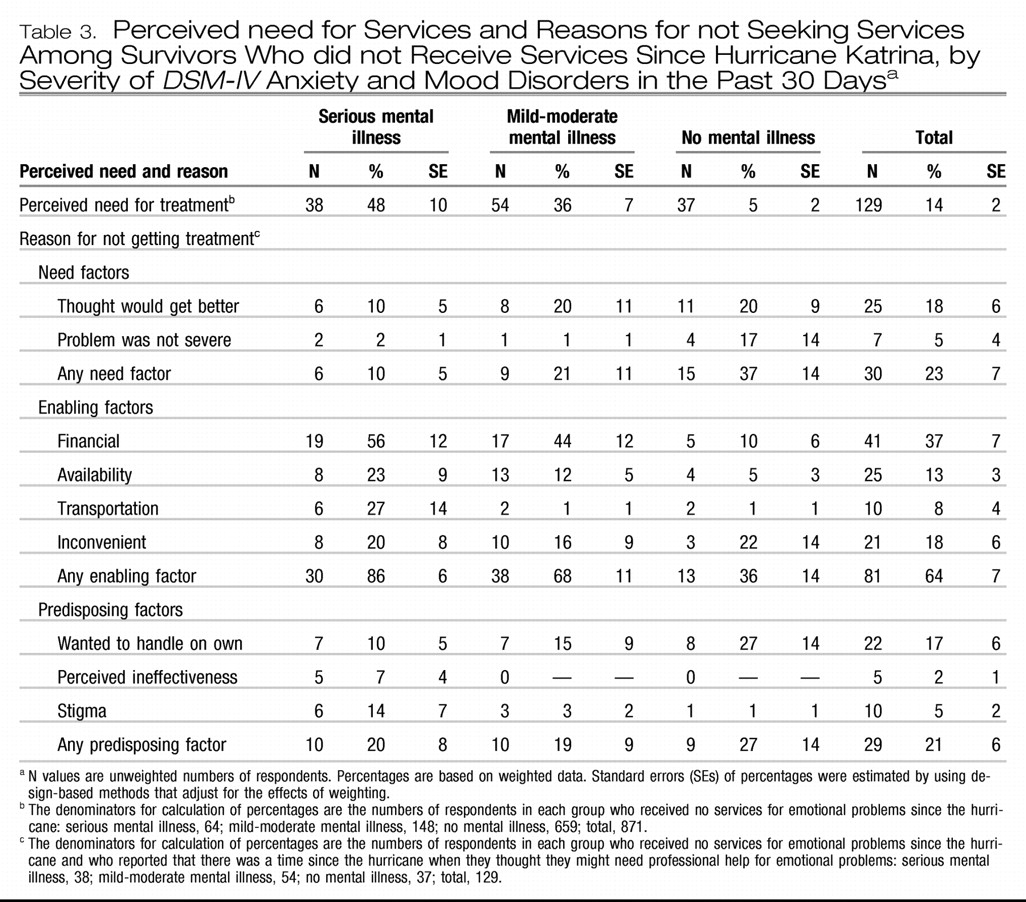

PERCEIVED NEED AND REASONS FOR NOT USING SERVICES

As

Table 3 shows, 14% of the respondents who reported not using treatment felt that they needed mental health care. The proportion ranged from 48% among those with serious mental illness to 5% among those with neither serious nor mild-moderate mental illness. Among those who perceived a need for treatment, nearly 64% reported a lack of enabling factors (for example, available services, financial means, and transportation) as a reason for not seeking care; the proportion ranged from 86% of those with serious mental illness to 36% of those with neither serious nor mild-moderate mental illness.

Low need (for example, thinking that the problem was not severe or would get better on its own) was reported as a reason by 23% of all respondents; the proportion ranged from 10% of those with serious mental illness to 37% of those with neither serious nor mild-moderate mental illness. Attitudinal or predisposing factors (for example, stigma, perceived ineffectiveness of treatment, or a desire to handle the problem on one's own) were reported by 21% of respondents; the proportion ranged from 19% of those with mild-moderate mental illness to 27% of those with neither serious nor mild-moderate mental illness.

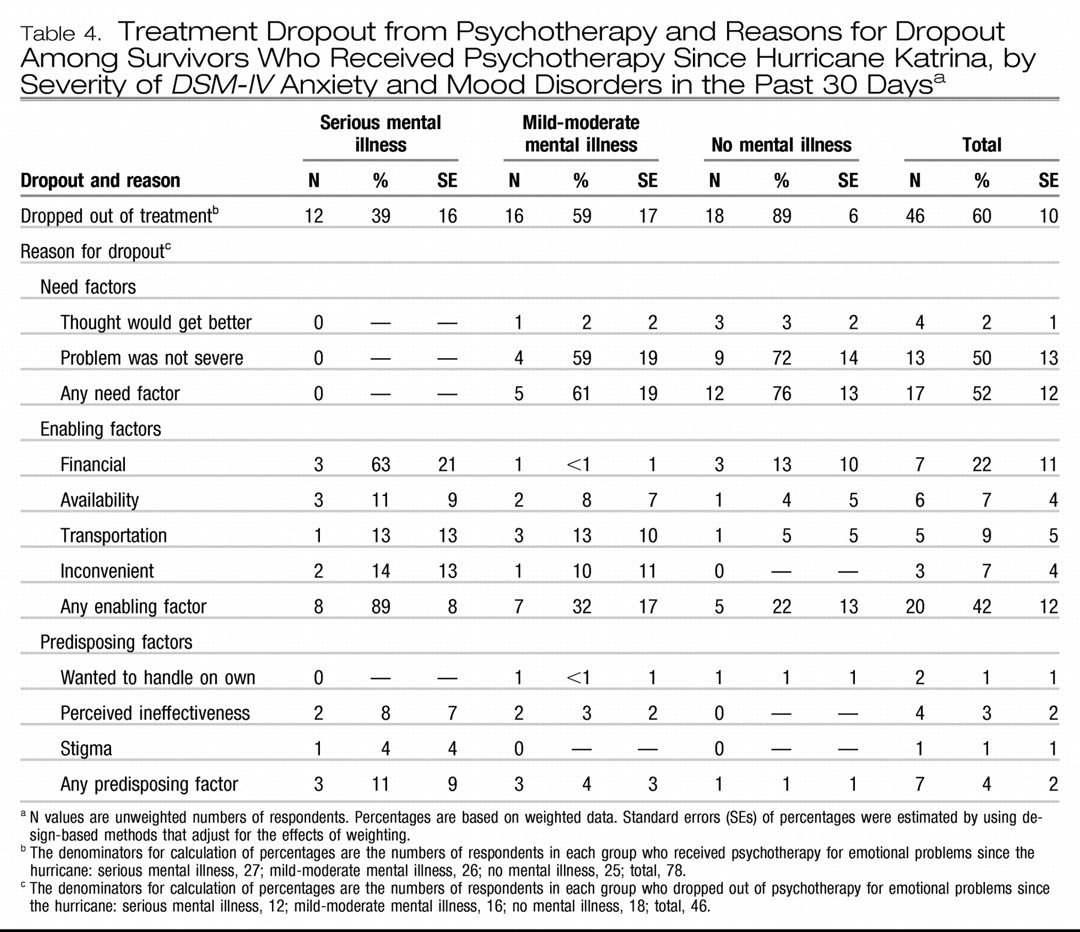

TREATMENT DROPOUT

As

Table 4 shows, 60% of respondents who had used psychotherapy since the disaster had dropped out of psychotherapy by the time of the interview; the proportion ranged from 39% of those with serious mental illness to 89% of those with neither serious nor mild-moderate mental illness. Among respondents who had dropped out, lack of enabling factors was a reason for 42%; the proportion ranged from 89% of those with serious mental illness to 22% of those with neither serious nor mild-moderate mental illness.

Low need was reported as a reason for dropout by 52%; the proportion ranged from none of those with serious mental illness to 76% of those with neither serious nor mild-moderate mental illness. Attitudinal or pre-disposing factors were reported by 4%; the proportion ranged from 11% of those with serious mental illness to 1% of those with neither serious nor mild-moderate mental illness.

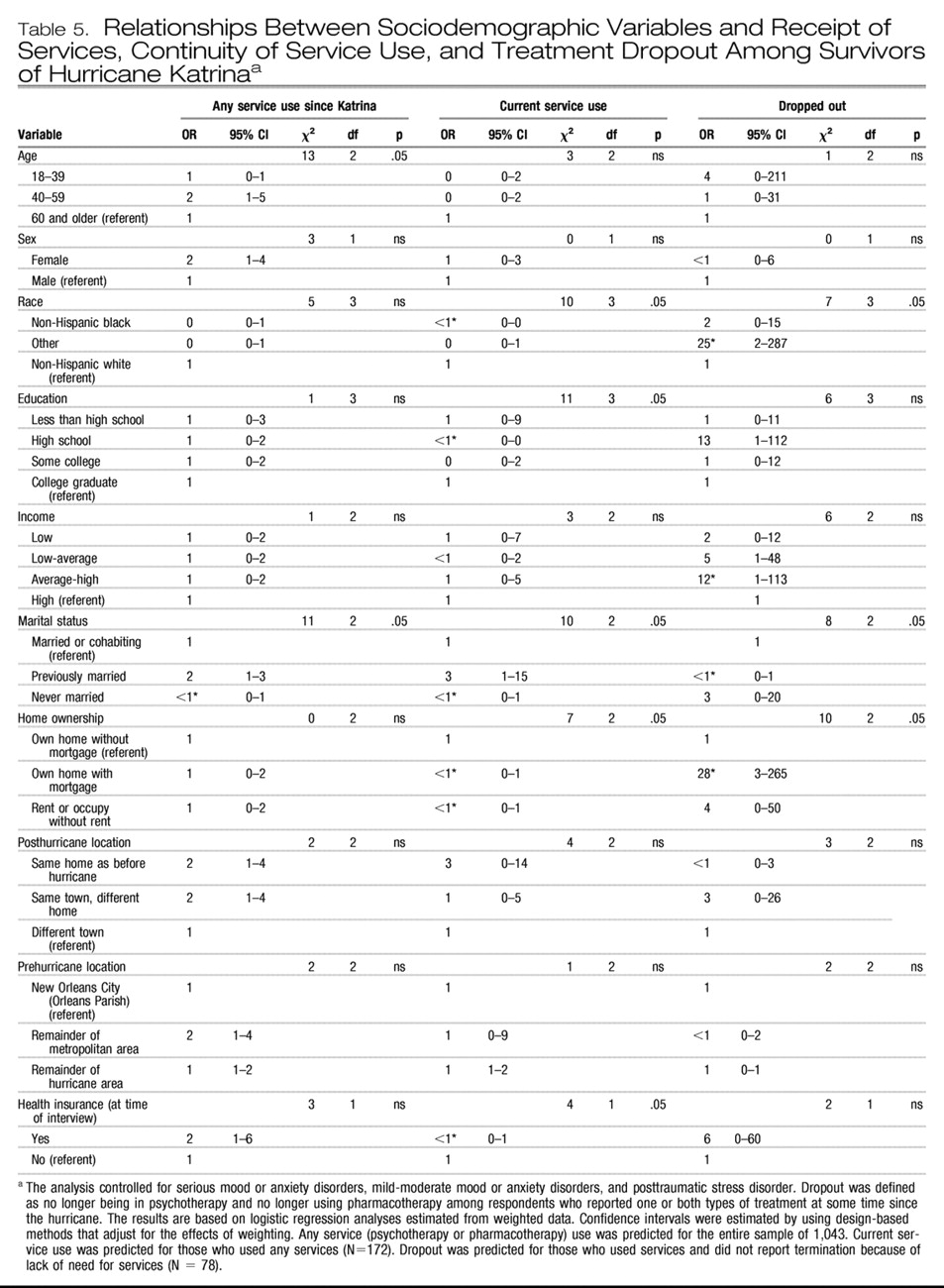

PREDICTORS OF RECEIVING TREATMENT AND DROPPING OUT

Table 5 presents data on predictors of receipt of services. After clinical variables were controlled for, significant predictors of receiving any treatment among all respondents included being middle-aged (compared with being older or younger) and being married at some point in one's life. Significant predictors of being in treatment at the time of the interview included being white, married at some point, having low or high levels of education, owning one's home without a mortgage, and having health insurance after the disaster.

Among respondents who had received any services since the disaster, significant predictors of dropping completely out of treatment (that is, no longer receiving any psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy) by the time of the interview included being of Hispanic or “other” race-ethnicity (that is, neither non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic black), never being married, and home ownership with a mortgage.

DISCUSSION

Results from this geographically representative survey of Hurricane Katrina survivors conducted between five and eight months after the disaster indicate that less than one-third of those with active anxiety or mood disorders received any form of mental health care after the hurricane. Although respondents with more severe disorders tended to use more mental health services, more than half of the respondents with the most severe disorders received no mental health care. Large proportions of those who used services received treatments of low intensity or frequency. Of those who did manage to access services at some point after the disaster, more than half dropped out of treatment by the time of the survey interview.

The limited data available on mental health service use after disasters corroborate our findings. Among evacuees living in Louisiana FEMA shelters, parents reported difficulties finding appropriate and accessible mental health services for both themselves and their children with mental health needs (

21). Use of mental health services has been surprisingly low even after disasters that were not marked by large-scale displacement or extensive destruction of infrastructure (

22–

24). For example, after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York, where the service infrastructure remained largely intact, only 11.3% of people with a mental disorder received any psychiatric help and only 26.7% of those with the most severe psychiatric symptoms obtained treatment by three to six months (

25). Only 15% of those directly affected and 36% with probable posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression sought mental health care by six months (

26).

Our findings may not be surprising given that Katrina struck people who before the disaster were among the poorest in the nation, many of whom were members of racial or ethnic minority groups. Although people with lesser means and those from minority groups are at higher risks of psychological sequelae from disasters, they are underserved when it comes to their mental health care needs (

27–

30). Furthermore, after the disaster there was widespread loss of mental health care facilities, treatments, and personnel. In addition, because of loss of employment many people lost financial resources and insurance to pay for care. For example, according to estimates made soon after the disaster, there were only two psychiatric beds available in all of New Orleans and its surrounding suburbs (

13,

31,

32).

In addition, many individuals with mental disorders have a low perceived need for treatment, while others recognize their need for treatment but avoid mental health care for fear of reexperiencing painful memories. Others avoid treatment because of the perception that mental disorders and treatment are associated with high levels of stigma (

33,

34). These attitudinal barriers appear to have caused many Katrina survivors with access to treatments to leave their mental disorders undertreated. The negative consequences of this widespread unmet need are uncertain but presumably large; dysfunction, morbidity, and mortality are associated with untreated mental disorders, and even subthreshold PTSD symptoms have been associated with poor functioning and suicidality (

35,

36).

Most Katrina survivors relied on the general medical sector for mental health care, which emphasizes the importance of ensuring that primary care personnel can deliver high-quality mental health treatments in disaster settings. On the other hand, the specialty sector played a large role, especially in the care of those with the most serious illness, indicating the need to have specialty personnel as well as coordinated triage plans during future disasters. Pharmacotherapy was the most commonly used modality, suggesting that current initiatives, such as the Strategic National Stockpile of emergency medications, include frequently used psychotropic classes (

37). Although psychotherapy was a less commonly used modality, it does appear to play an important role in the care of those with serious disorders and in promoting treatment continuity, especially in combination with pharmacotherapy.

Other correlates of service use were generally consistent with those found in previous research, including the few studies of disaster survivors. Lower service use by young and elderly persons may be attributable to the greater dependence of younger individuals on others to access treatments and on the greater stigma of mental disorders and treatments in older populations (

22,

38–

41). People who were never married may lack social supports needed to initiate or remain in treatments (

22,

25). Individuals of modest means, as reflected by middle levels of education and home ownership, may be at greatest risk of undertreatment—not only do these persons have fewer resources to pay for treatments but they also do not qualify for entitlements reserved for the severely disadvantaged population (

26,

42). Finally, we found that having insurance was associated with continuing in mental health treatments, which is similar to findings among persons affected by the World Trade Center disaster (

23). This finding is worrisome given that 20% of the nonelderly population in Louisiana and Mississippi were uninsured before Katrina and this proportion swelled after the disaster because of job losses (

31,

32,

43,

44).

These results should be interpreted with several limitations in mind. The survey excluded people who were unreachable by telephone, which led to underrepresentation of the most disadvantaged and possibly most severely ill people. Systematic survey nonresponse or nonreporting are also possible and may have led to underestimates of unmet needs for mental health treatments (

18,

45–

49). Psychopathology was assessed using a brief screening scale rather than a clinical interview; however, good concordance with clinical interviews has been consistently documented in published reports (

17,

18). Further-more, we considered only survivors with active psychopathology after Katrina; how the disaster may have affected the particularly vulnerable subgroup of persons who had predisaster mental disorders requires further study. Without corroborating data we do not know the validity of the self-reported data on treatment use; some investigators have found that self-reports of mental health service use overestimate treatment, especially the number of visits and especially among respondents with more distressing disorders (

50,

51).

To reduce respondent burden, we did not ask extensive questions about service use or potential barriers to help seeking. We thus were unable, for example, to distinguish between social worker visits in the specialty mental health care sector and those in the human services sector, although this is unlikely to have materially affected our findings given the small number of respondents who reported making social worker visits. Likewise, the extent to which specific attitudes may have deterred treatment seeking is unclear; for example, older adults may hold an altruistic view that services should be reserved for younger survivors. Finally, the survey's cross-sectional nature prevents us from concluding that the observed correlates and reasons are causally related to mental health service use.

Experiences with Hurricane Katrina have shown that many survivors with mental disorders fail to receive needed treatments in the aftermath of complex disasters (

52). On the basis of such lessons, what can be done to meet the needs of survivors of future disasters and to deal with financial, structural, and attitudinal barriers to mental health care? Informational resources on disaster-related mental disorders and their treatment, such as those developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and other organizations, should be provided and promoted, but clearly these alone will not be sufficient (

53).

To help survivors pay for treatments, emergency insurance coverage, such as Medicaid waiver programs enacted after the World Trade Center disaster and by 17 states for Katrina survivors, may be essential (

43,

54). Local personnel could be organized to provide crisis counseling and referrals as in Project Liberty after the World Trade Center terrorist attacks but only in areas where clinicians and infrastructure remain (

55). Emergency mental health units could be stationed in devastated areas, as has been done in Operation Assist in Louisiana and Mississippi (

21). However, novel strategies may be necessary to reach widely dispersed populations of evacuees; for example, personnel outside affected areas could be employed to remotely deliver services such as cognitive-behavioral therapy over the telephone (

56).

All strategies chosen should anticipate and address common attitudinal barriers among survivors that can undermine programs in which services are only passively made available (

42). Screening and aggressive outreach programs that have already shown promise in overcoming such barriers and enhancing mental health treatments in primary care populations may also be useful in disaster settings (

56).