The major problem limiting the effectiveness of mental health care is the failure to promote well-being due to an excessive contemporary focus on deficits symptomatic of mental ill-being. Our treatments focus on symptoms rather than on causes of dysfunction and fail to promote healthy functioning. As a result, improvements in treatment are usually weak, incomplete, and temporary, whether based on psychopharmacology or psychotherapy (

1). In contrast, randomized controlled trials of treatments designed to promote well-being have been shown to reduce dropout, relapse, and recurrence rates compared with treatments for symptoms of disorder (

2–

4). In addition, psychiatric care to promote well-being reduces the stigma and increases recovery of mental health. In other words, mental health care appears to be more effective than mental illness care.

An understanding of personality development provides a systematic way to promote health, which can be defined as an integrated state of physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being, rather than merely the absence of disease or infirmity (

5,

6). More specifically, mental health has been described as “A state of well-being in which the person realizes and uses his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to his or her community” (

6). This definition of mental health corresponds closely to the description of maturity of personality, particularly the character traits of self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence, which allow a person to work, love, and serve others. In fact, there is extensive data indicating that individual differences in personality are causal antecedents contributing to the full range of psychopathology (

7).

Mental health professionals and educators use a wide variety of methods for the development of character and well-being. The traditional mainstays of psychiatric treatment have been various forms of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, but there are also many other effective evidence-based treatments that promote greater mind-body awareness by means of work on physical exercise, diet, sleep hygiene, deep breathing exercises, guided imagery, muscular relaxation, or meditation (

8–

10). The effects of conventional and alternative methods are often indistinguishable, suggesting that some common mechanism is being influenced by complementary pathways (

11). How do these diverse biological, psychological, and social interventions influence well-being? One clear answer has been given to this question by sages throughout history (

1). Well-being and the integration of personality depend fundamentally on self-awareness, as summarized in the Delphic injunction to “Know Yourself.” Rather than relying on the authority of ancient sages, however, here we will consider evidence to evaluate the possibility that character development can be facilitated by diverse methods that enhance a person's awareness of any aspect of their being, including their body, thoughts, or psyche. To do so, we must evaluate ways of measuring the different aspects of being and well-being. Each of these terms and their aspects need to be clearly defined and measured in ways that can be implemented efficiently in clinical practice, as we will describe in detail. We must also consider the mechanisms by which increasing awareness may promote increased well-being and reduced ill-being.

First, we review the relationship between personality and a wide range of psychiatric disorders. Second, we evaluate the impact of character structure on a wide range of measures of well-being, including positive emotions, negative emotions, life satisfaction, perceived social support, and perceived health. Third, we describe a practical and inexpensive clinical method for facilitating the maturation and integration of personality based on an understanding of the processes of human thought, which underlie changes in personality and well-being.

THE RELATIONSHIP OF PERSONALITY AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

Personality traits are an important component of the complex development of the full range of psychopathology but do not explain most of the variance in risk for psychiatric disorders. The incomplete determination of psychopathology by personality is partly related to the incompleteness of what is traditionally called personality. A fuller account of all aspects of a person needs to include sexuality, physicality, emotionality, intellect, and spirituality in an integrated developmental perspective (

14). Furthermore, the development of psychiatric disorders depends on internal and external variables that pull on the self, such as the appropriateness of a person's life style, goals, and values within the personal, social, and cultural setting in which they live (

15). We cannot separate the self or the whole person from their family or culture any more than we can separate a person's body and mind. Efforts to do so result in “brainless” or “mindless” perspectives, which eventually lead to confusion rather than understanding (

16,

17).

As a result of such complexity, we must be modest about the extent to which personality explains the etiology of psychopathology. Yet it is also clear that personality variables contribute to most psychopathology and that the integration of personality allows such improved adaptation that people can enjoy the way they have learned to live well with the strengths that they always had or the abilities that they can acquire with experience or treatment. This is the modest etiological but hopeful therapeutic claim that we think is justified by what we know about personality development:

Nearly all human beings have enough capacity for self-awareness to allow them to learn how to live well—with satisfaction, purpose, and a sense of meaning greater than their individual selves, even if their self-awareness is initially limited. Some randomized controlled trials have been done to directly support this claim using diverse methods to increase awareness of the body, thoughts, and psyche of a person (

2,

4,

8–

11), but much more is needed before this claim can be considered well-documented. Our limited knowledge of the science of well-being is a well-known reality that every practicing psychiatrist already faces daily with each patient encountered. What all mental health professionals need is a practical way to help people make their lives better. So here we will review the facts that are available to guide such a hopeful person-centered approach to well-being.

THE SIMILARITY OF PERSONALITY VARIANTS AND MAJOR CLINICAL SYNDROMES

Psychiatrists have been divided by interest and training into schools that emphasize the importance of major categories of illness, as described on axis I of DSM, or the development of personality traits, as described on axis II of DSM. Sometimes these distinctions have been confounded with the belief that neurobiology or nature causes the major categories of illness, whereas psychosocial development or nurture causes personality traits. The dichotomies of nature or nurture, neurobiology or psychosocial development, and category or trait are no longer scientifically tenable perspectives (

17). The brain does not have centers for different categories of illness; it is modular, with each module having functions that participate in a variety of integrative processes in combination with other modules to allow purposeful adaptation to internal and external events. These modules are extensively interconnected, like the Internet, so that communication operates as a nonlinear dynamic system with quantum-like properties (

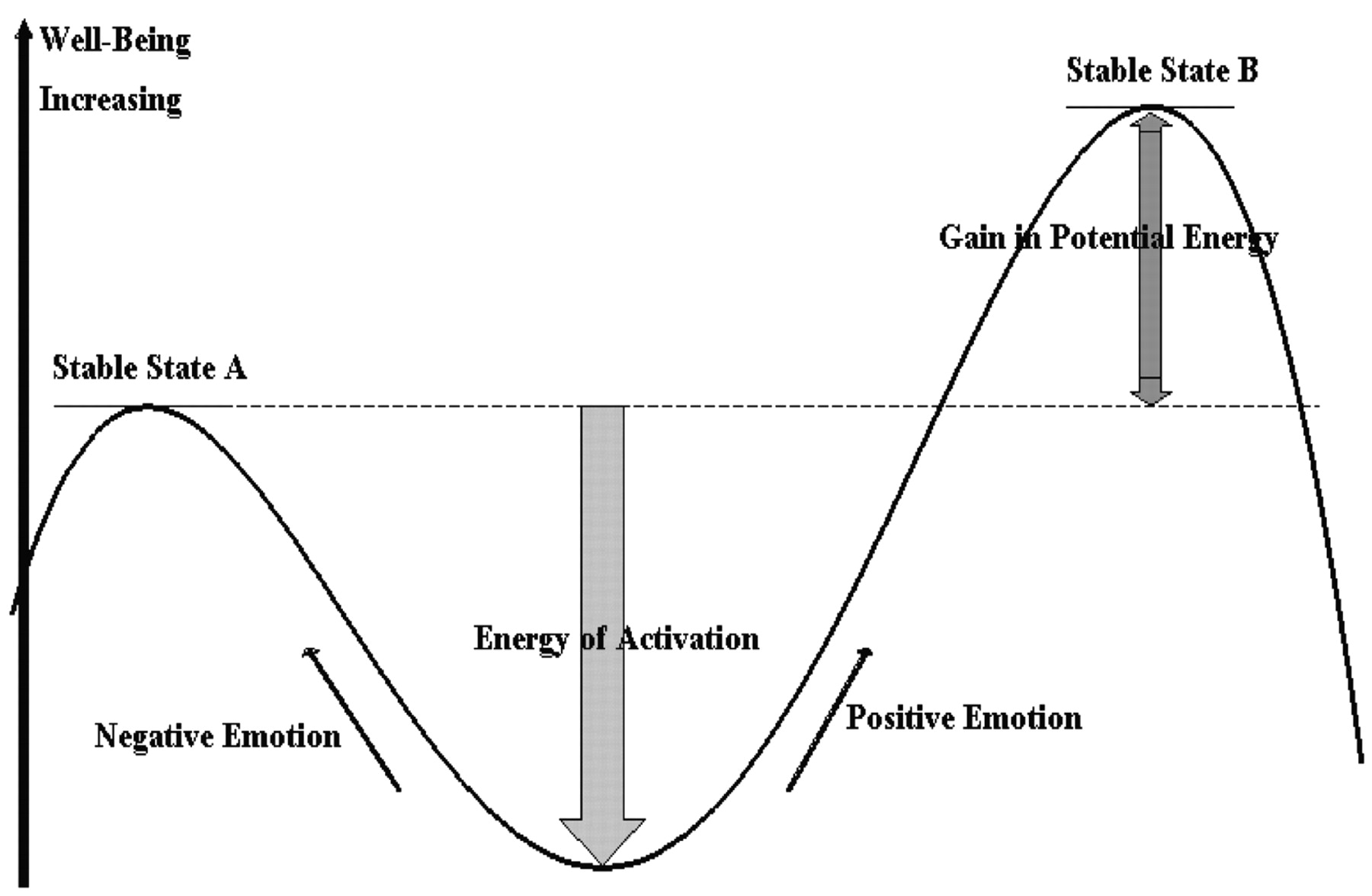

1). The dynamics of shifts in brain states is depicted in

Figure 1. The two brain states, A and B, in

Figure 1 represent different configurations of a person's brain modules. The two brain states or configurations of personality differ in their level of information content and well-being. These states are technically described as “metastable”: a person can be stuck in the less well configuration A because the only way to reach the more well configuration A is by temporarily giving up some of the advantages or pleasures associated with configuration B. In clinical terms, people must face who they are and recognize both the advantages and disadvantages of their current way of living and of other potential attitudes toward life before they can change without self-defeating conflict. As a result of such relative stability, configurations of traits can appear to be a categorical disorder temporarily until they radically transform, usually in the flash of a moment of insight leading to a change in outlook.

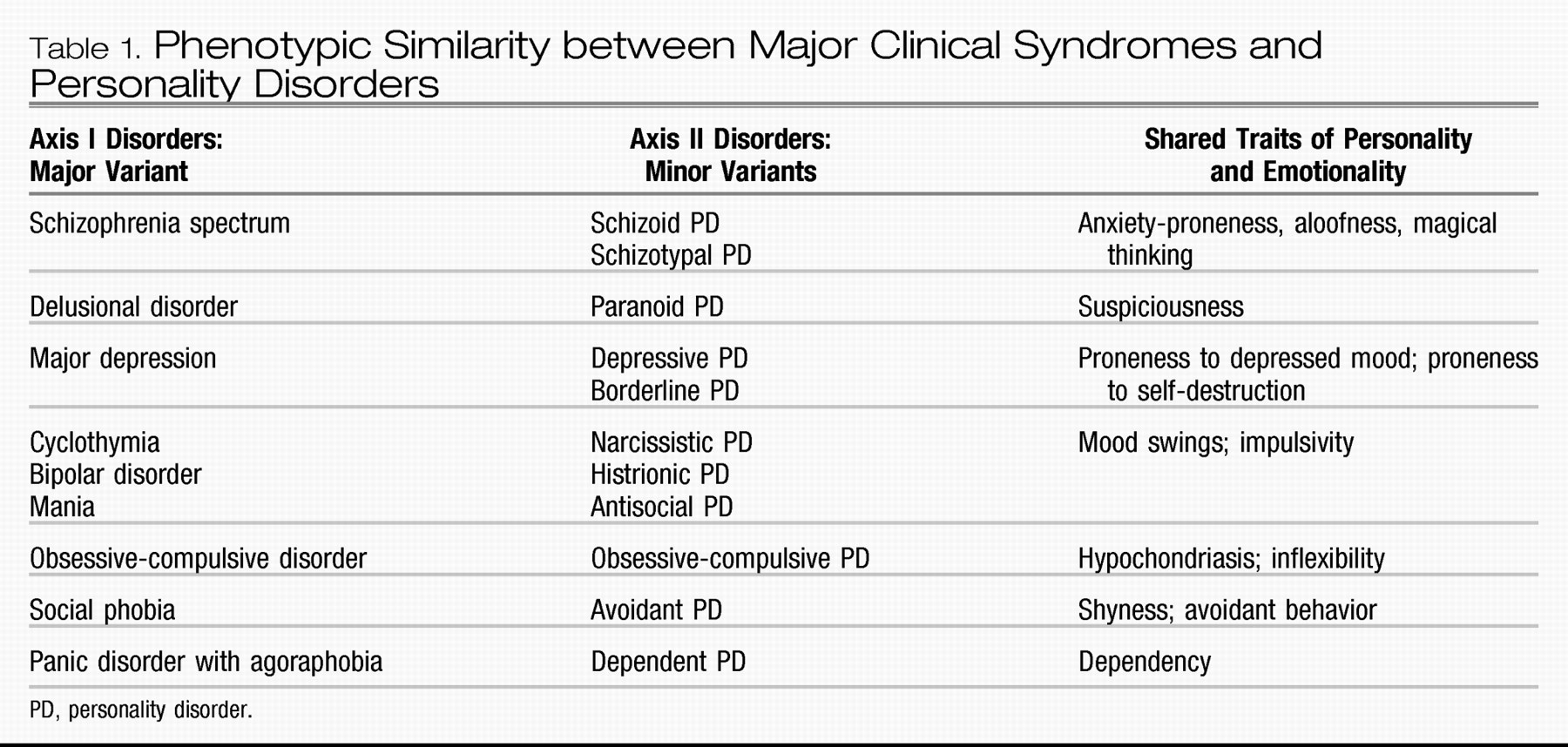

It is important for clinicians of all perspectives to recognize that there is substantial similarity in diagnosis and treatment whether viewed through the lens of major clinical syndromes, personality disorders, or the traits they share in common. The similarity between major syndromes and personality disorders is illustrated in

Table 1. Although it may seem surprising to people accustomed to a biomedical model, even the major syndromes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder are strongly influenced by premorbid personality traits (

18–

21). As previously mentioned, temperament and character may not explain all of the components of a clinical syndrome, but their contribution is usually sufficient to effect recovery by understanding the personality configuration that led to vulnerability to the disorder.

ANTICIPATING AND UNDERSTANDING COMORBIDITY

Remember that personality traits occur in all possible combinations, whereas clinicians are accustomed to thinking as if a person has only one basic diagnosis. In fact, we know that there is extensive overlap among the major clinical syndromes, so that having a mood disorder or schizophrenia does not provide any protection from having other disorders. The phenomenon of comorbidity has revealed the fundamental inadequacy of categorical diagnosis (

103). Once a clinician realizes that the syndromes are not mutually exclusive diseases and that they actually share many functional components, then the clinical utility of multidimensional personality assessment becomes clear. Our diagnostic and treatment processes are greatly facilitated by having a way to understand the patterns of comorbidity that we observe in people by knowing what their personality structure is. Once we know the personality structure, we can often anticipate what other problems individuals may have even if they did not volunteer the information in their initial presenting complaints.

For example, the TCI profile allows clear prediction of what comorbid syndromes are present in people presenting with any diagnosis, such as a major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder (

19,

50,

104). If persons presenting with a mood disorder has high harm avoidance, which they usually do, then they are likely to have comorbid anxiety and somatization. If patients with major depression have high novelty seeking, they are likely to have comorbid syndromes associated with poor impulse control such as substance dependence, bulimia, binge eating, or pathological gambling. And vice versa, if patients with depression has substance dependence we should investigate whether they are high in novelty seeking. If patients with major depression are low in cooperativeness, we can anticipate that they will have problems with hostility or suspiciousness. The structure of personality forms a clear scaffold on which we can systematically organize our thinking about the functional interactions that occur over the course of people's lives as they shape and adapt to an ever-changing internal and external environment. We can see that every component of personality is always important in adapting rather than trying to oversimplify human motivation by reducing it to a fuzzy set of idealized categories that are really metastable configurations of dynamic functional processes by which people seek health and happiness with more or less success (

105).

PERSONALITY AND WELL-BEING

In addition to understanding the relationship of personality to psychopathology, a mental health professional also needs to understand the relationship of personality to health as a state of physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being (

6). To proceed scientifically, we must be able to measure these aspects of well-being in a reliable way. We studied personality with the TCI and related it to well-validated measures of well-being in 1,102 consecutive community volunteers from the Sharon region of Israel (

106). The measures of well-being we used were the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (

107), the Satisfaction with Life Scale (

108), and the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (

109). Perceived health was also rated on a five-point Likert scale based on the item “How would you rate your health over the past 30 days?” from the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (

110).

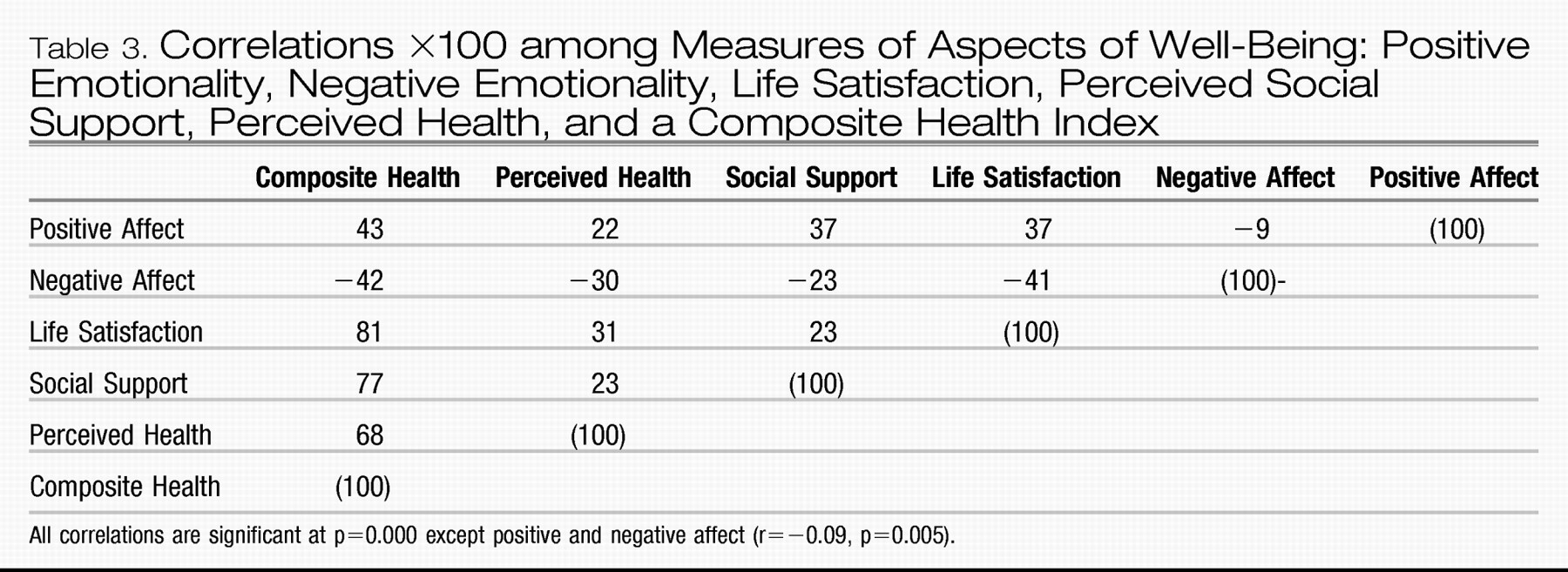

Table 3 summarizes the correlations among these measures. Positive and negative affectivity were largely uncorrelated (r=−0.09), which reminds us that the presence of positive affect (i.e., happiness) is not at all the same as the absence of negative affect (i.e., not being depressed or upset). Scores for life satisfaction, perceived social support, and perceived health were weakly but positively correlated with one another (r=+0.23–+0.31), so we formed a Composite Health Index (CHI) as the mean of these three measures.

Table 3 shows that each measure of health was strongly correlated with the CHI (r=+0.7–+0.8). These findings show that health and happiness are correlated but made up of distinguishable components of physical, mental, and social well-being, as suggested by the World Health Organization definition of health (WHO, 1946).

Next we began to consider the way a person's character profile influenced these components of well-being. From prior work reviewed in the preceding section, we knew that recovery from mental disorders in prospective treatment studies involved greater maturity or adaptability of TCI character traits. In contrast, measures of well-being have little relationship to temperament traits except for harm avoidance (

111). Prior work had suggested that a gradient in adaptiveness of character could be described along an approximate gradient shown in

Figure 2 from the creative character (designated as SCT) with high self-directedness, high cooperativeness, and high self-transcendence to the depressive character (designated as sct) with low self-directedness, low cooperativeness, and low self-transcendence. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the relationship between character configuration and well-being for each of the measures of well-being in

Table 3.

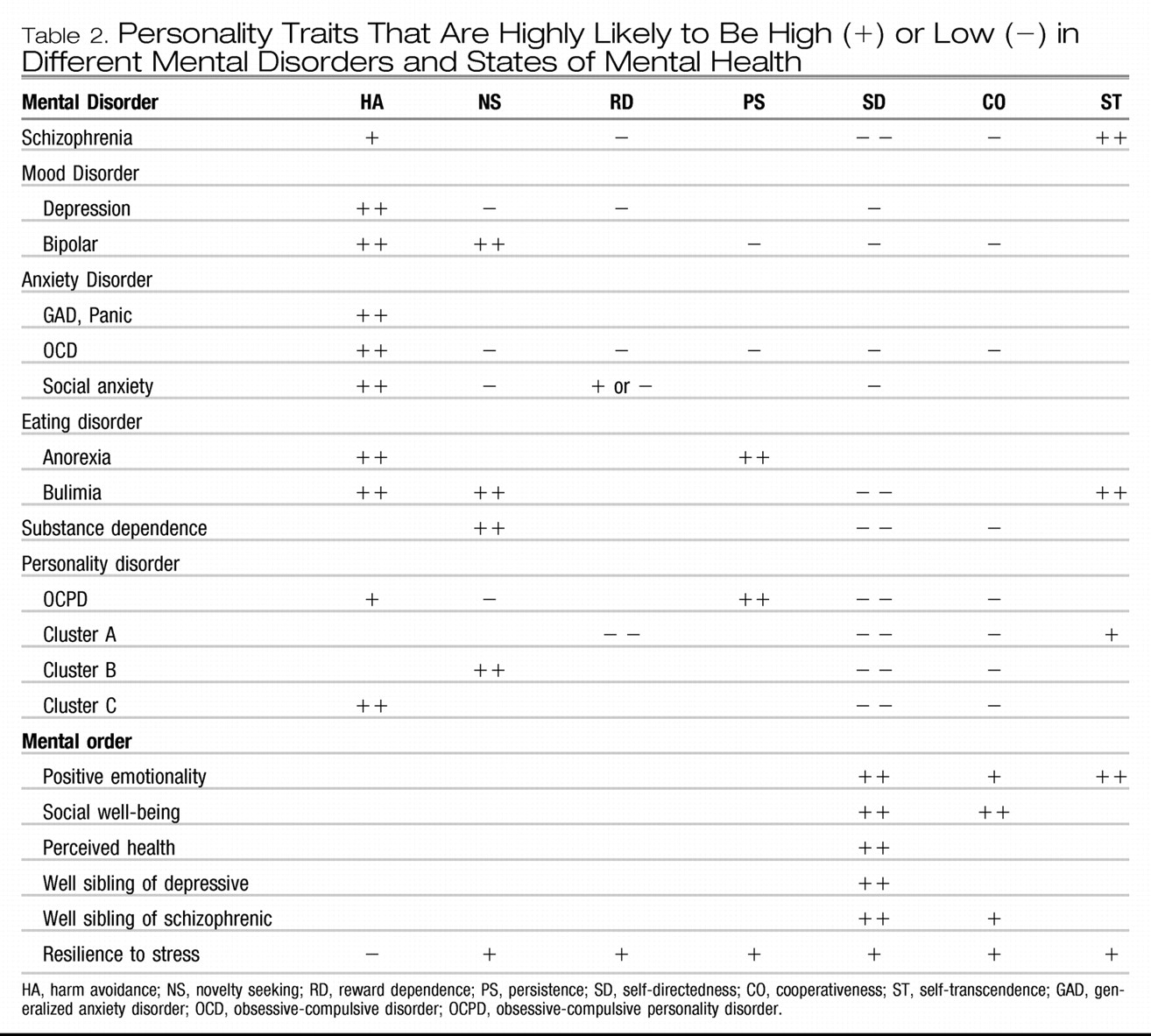

Overall results are summarized in

Table 2 for well-being in a format that parallels that for mental disorders. We will consider each of the measures in sequence to describe the way each character trait has distinct functional effects while interacting with the other traits.

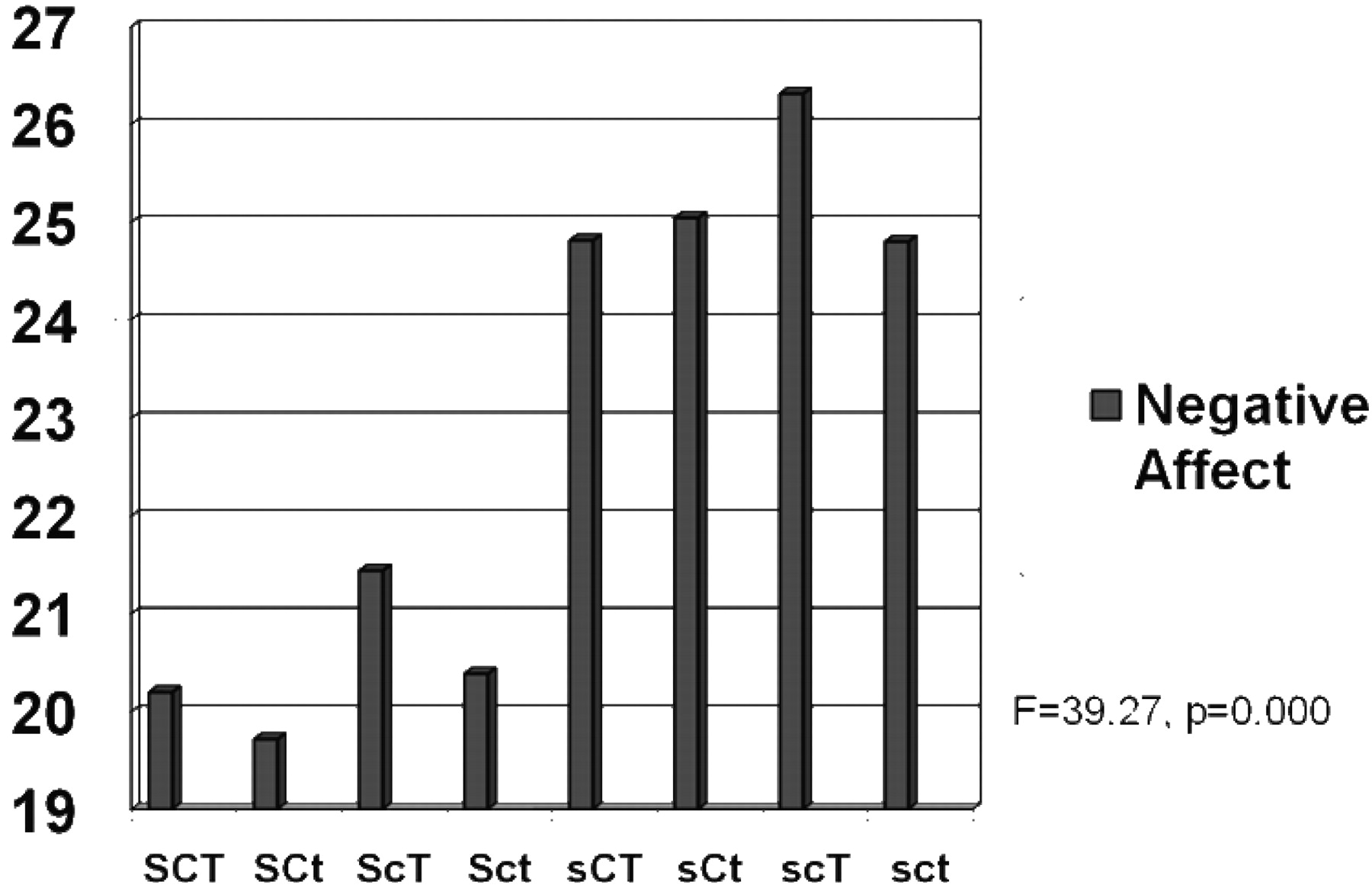

First, let's consider the relationship of character structure to the differences between individuals in negative affect (“unhappy”), as depicted in

Figure 2. All four character configurations with high self-directedness had less negative affect than those with lower self-directedness, demonstrating a strong association of self-directedness with lower negative affect. Cooperativeness had a weak association when self-transcendence was high: higher cooperativeness was associated with lower negative affect in the contrast between moody and disorganized profiles (sCT versus scT) and between creative and fanatical profiles (SCT versus ScT). Self-transcendence was not associated with lower negative affect in any contrast.

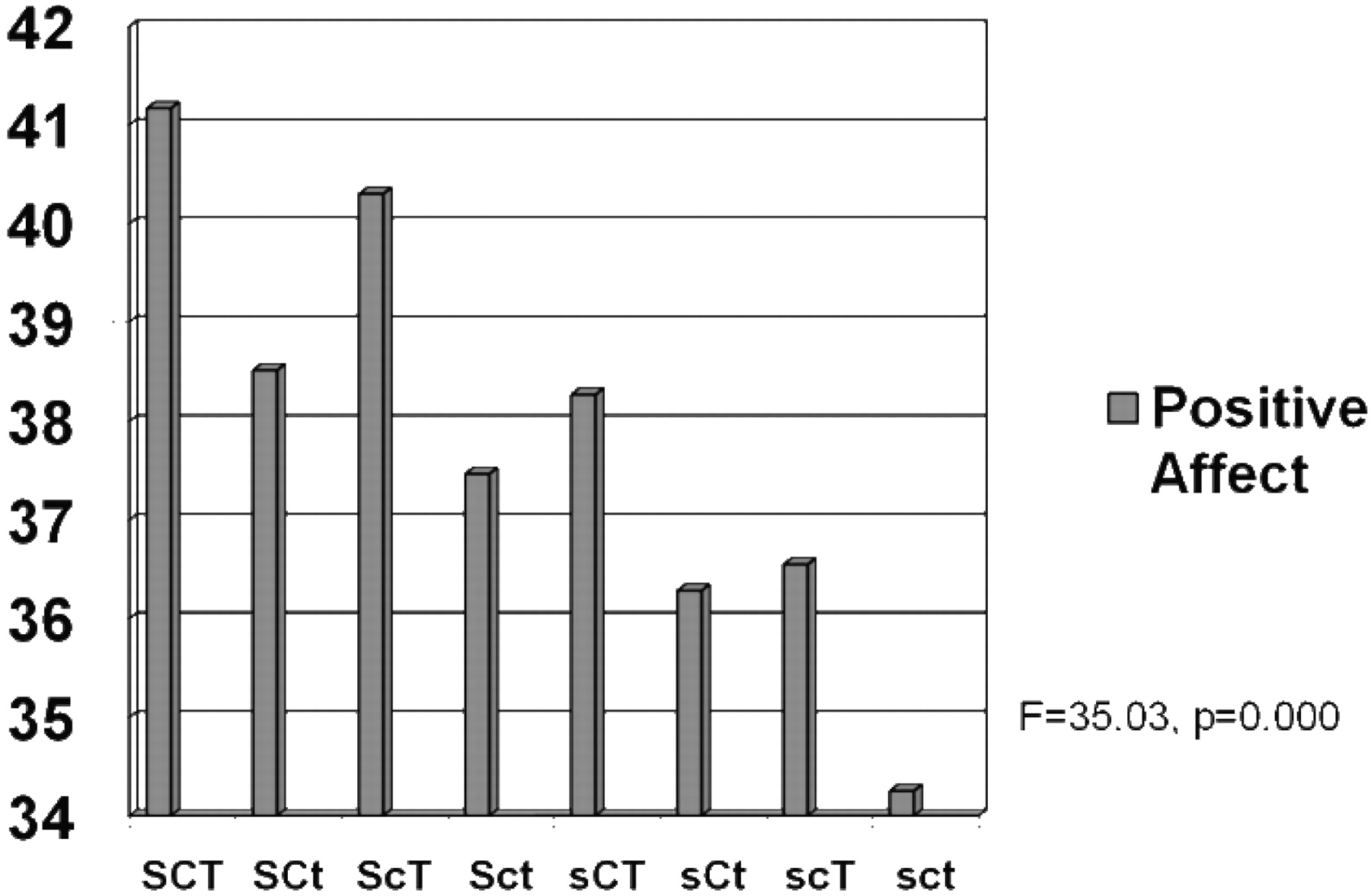

The interactions of character dimensions on positive affect, depicted in

Figure 3, were different from those observed for negative affect. Higher self-transcendence was consistently associated with higher positive affect for each of the four possible configurations of self-directedness and cooperativeness (SCT versus SCt, ScT versus Sct, sCT versus sCt, and scT versus sct). Likewise, higher self-directedness was consistently associated with higher positive affect for each of the possible configurations of the other two characters. The association of higher cooperativeness with positive affect was also highly significant when self-directedness was low: higher cooperativeness was associated with higher positive affect than lower cooperativeness in the contrast of moody versus disorganized profiles (sCT versus scT) and for dependent versus depressive profiles (sCt versus sct). When self-directedness was high, higher cooperativeness was weakly associated with higher positive affect (SCt versus Sct and SCT versus ScT). In other words, the association of character profiles with positive affect was dependent on specific combinations of traits.

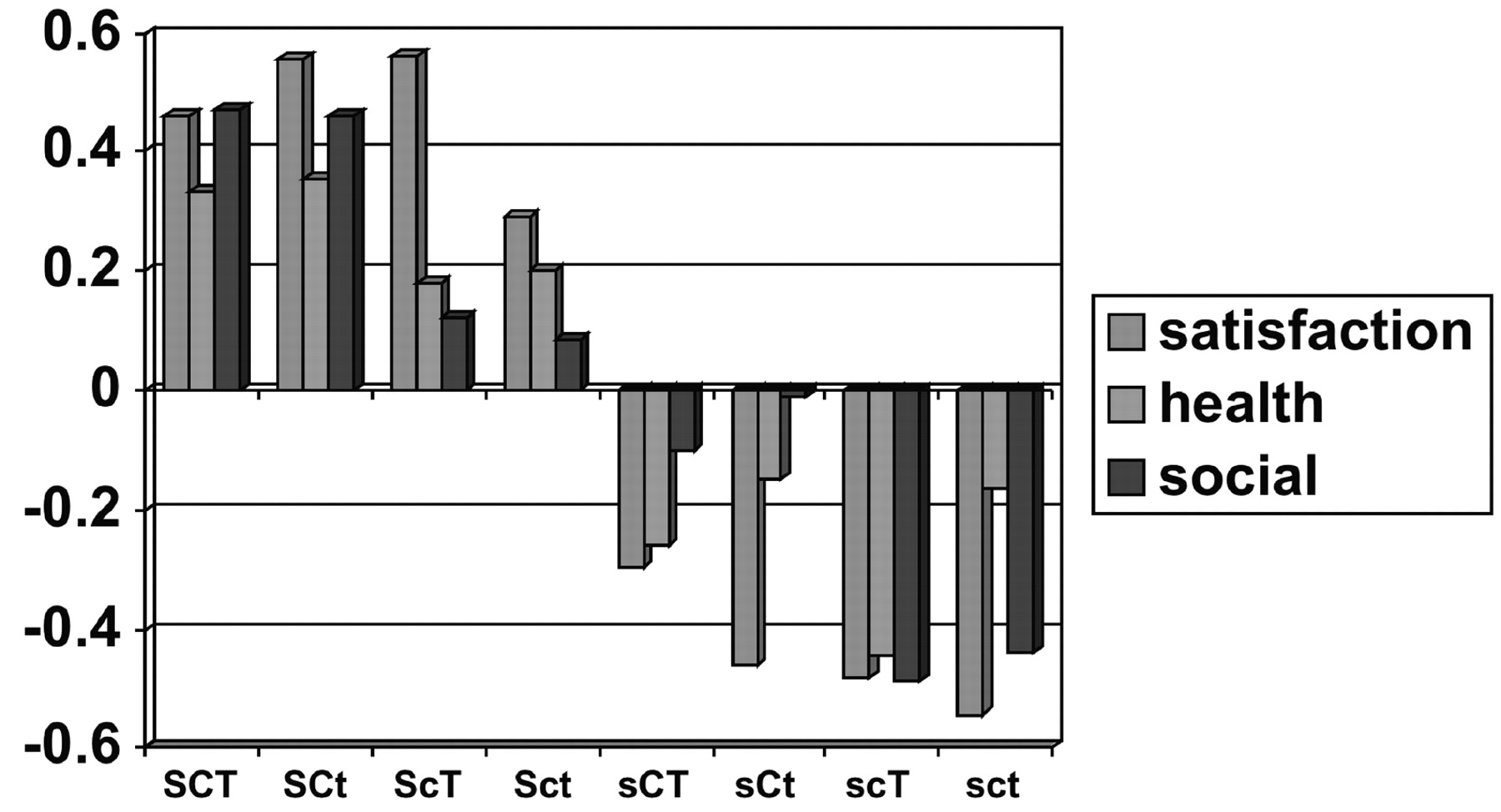

Likewise we evaluated the relationship between character profiles and the other measures of well-being shown in

Figure 4. Profiles with higher self-directedness were again consistently associated with better life satisfaction, perceived social support, and perceived health than those with lower self-directedness. In addition, profiles with higher cooperativeness were associated with greater perceived social support than those with lower cooperativeness.

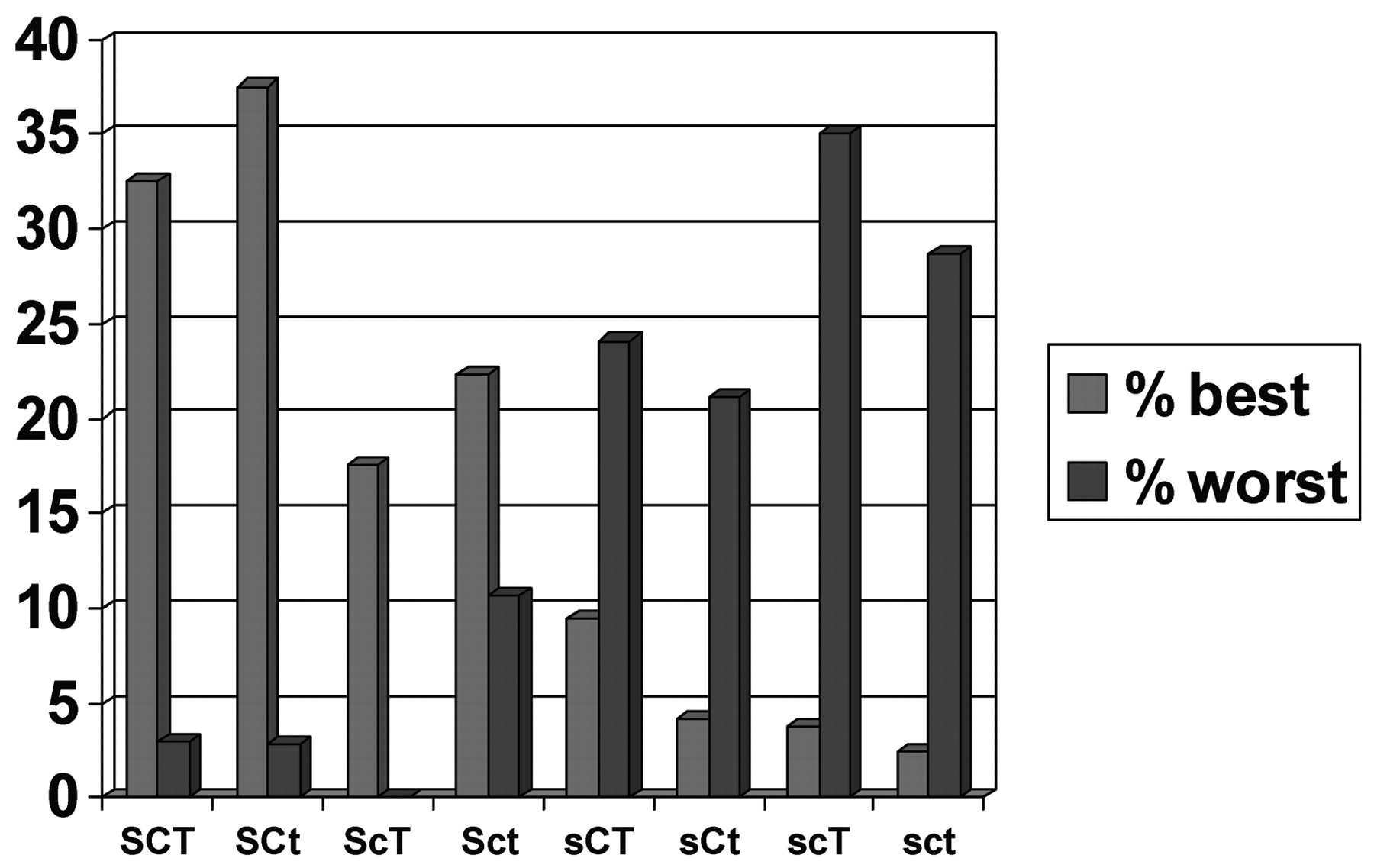

Another way to recognize the impact of character structure is to examine the proportion of people with each configuration who are in the top sixth and the bottom sixth of the population in overall health as measured by the CHI.

Figure 5 illustrates the strong impact of self-directedness on health.

As summarized in

Table 2, high self-directedness is consistently associated with all our measures of well-being: lower negative affect, higher positive affect, greater life satisfaction, greater perceived social support, and better health. Accordingly, highly self-directed people are typically described as hopeful. Cooperativeness is associated with greater social well-being as measured by perceived social support. Accordingly, highly cooperative people are typically described as loving. Self-transcendence is associated with greater positive affect, so self-transcendent people are often described as exuberant or joyful. Self-directedness has pervasive importance for the development of well-being, but each aspect of character makes a unique contribution.

These results in a general community sample confirm the results of work reviewed in the prior section showing that character development has a crucial role in recovery from ill-being and the development of well-being. How then can character and well-being be systematically developed?

A PSYCHOBIOLOGICAL APPROACH TO THE CULTIVATION OF WELL-BEING

Today many psychiatrists have limited time for psychotherapy, but nevertheless there is a great unmet need for ways to help facilitate character development. Personality assessment methods such as the TCI do enhance a clinician's practice by promoting a person-centered therapeutic dialogue (

112). However, additional methods need to be integrated with personality assessment to promote character development and well-being in a systematic way. We are proposing use of a multi-method psychoeducational course developed by C. R. Cloninger in consultation with the Anthropedia Foundation for the purpose of promoting growth in self-awareness (

2). The course, available on a set of DVDs (Anthropedia,

http://anthropedia.org) integrates experiences and practices that promote growth in self-awareness with evidence-based techniques from a wide variety of therapeutic approaches (cognitive-behavioral, person-centered, psychodynamic, logotherapy, well-being therapy, positive psychology, and others) and engages patients in practices that stimulate the development of the prefrontal cortex and lead to well-being (

1,

2). The course combines assessment of temperament and character with a self-directed exploration of personal well-being.

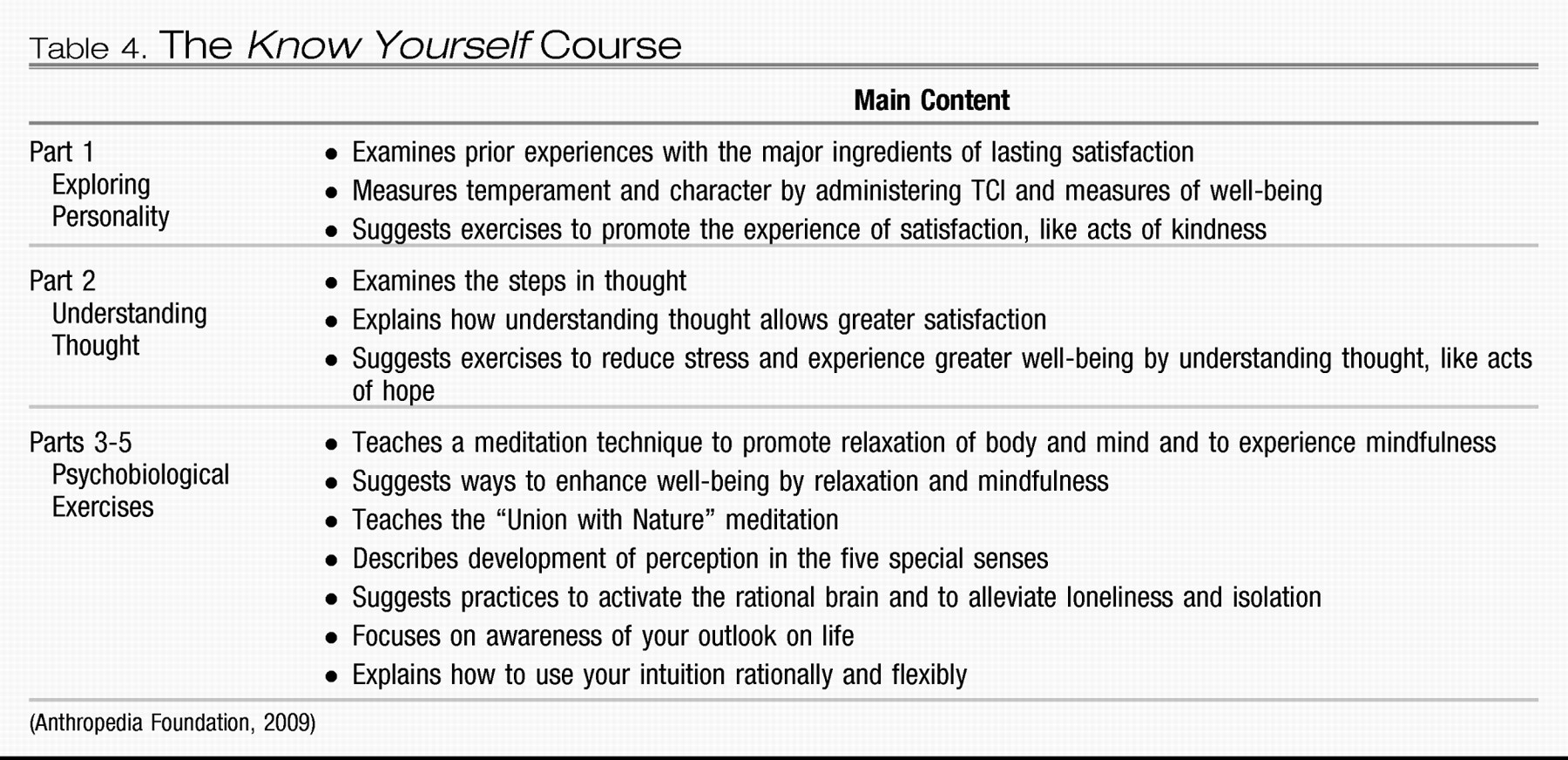

The course contains five distinct modules or sections (

Table 4). In the first module, a patient takes the TCI along with other brief measures of emotionality and life satisfaction to provide a baseline assessment and to stimulate reflection (

107,

108). The patient reflects on what has provided lasting personal satisfaction in the past to improve his or her self-knowledge and become more likely to work toward satisfying goals. This self-exploration can help motivate the patient for constructive change, as well as help to establish a therapeutic alliance (

112–

115). Self-observation about attitudes characteristic of well-being (

1) and related evidence-based exercises that promote satisfaction, such as practicing acts of kindness, suggest ways for the patient to begin to know himself or herself better (

116). Functional brain imaging shows that such exercises activate the medial and anterior prefrontal cortex (Brodmann areas 8, 9, and 10), which is implicated in self-aware processes characteristic of self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence (

1,

117–

120).

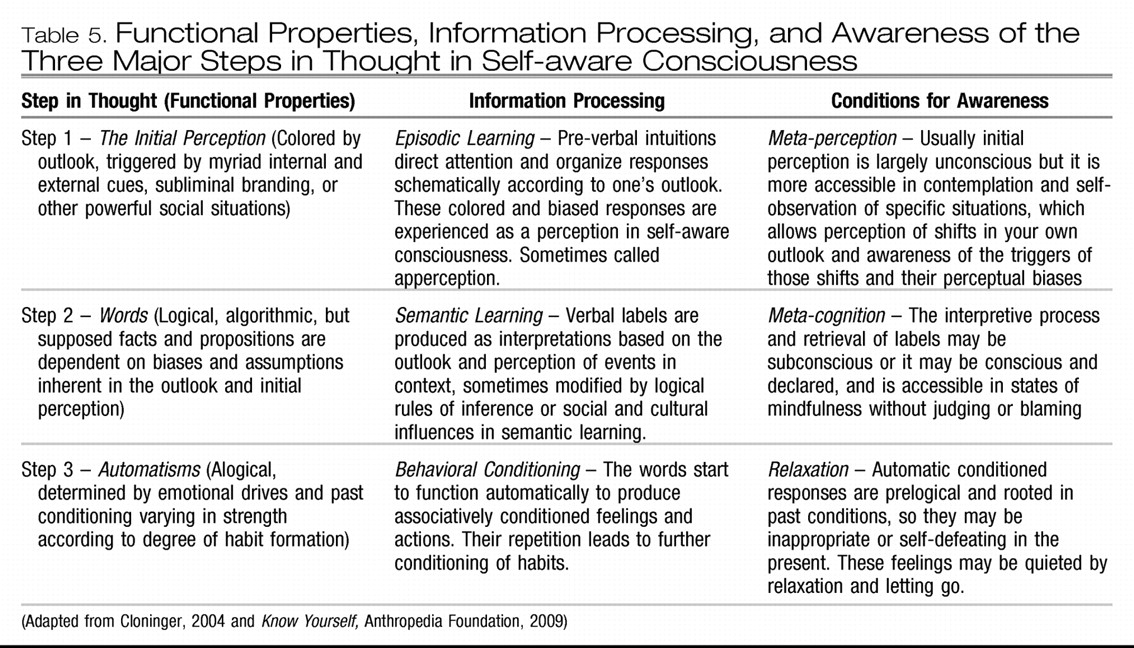

The second part of the course requires the patient to examine the steps of thought to understand the processes of thought that can lead to greater life satisfaction (

Table 5). This extends cognitive-behavioral descriptions of thought to recognize the three major systems of learning and memory that have evolved in the long evolutionary history of human beings (

14,

121). Once patients have begun to reflect on and identify what they find satisfying and to realize that their current habits of thinking may be interfering with their health and happiness, modules three to five of the course provide meditations and exercises to help patients activate their prefrontal cortex so that they can be more aware. Each exercise builds on the other but focuses on a different aspect of the being and a different system of learning. Specifically, patients first learn a simple meditation for relaxing the body and calming the emotional brain and then observing their own flow of thoughts to understand without judging or blaming. With this introduction, most people can begin to experience mindfulness and let go of judging and blaming (

1,

122,

123). Then the next two modules help to enhance this natural ability.

A second meditation is introduced to stimulate perception using all five senses in a way that is harmonious and joyful. Such voluntary activation of integrative sensory processing is designed to facilitate the perception of unity and harmony, which activates the medial and anterior prefrontal cortex and facilitates the development of rational intuition and emotional regulation. Use of rational intuition without judging or blaming is associated with deactivation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex along with activation of the medial and anterior prefrontal cortex (

124). Syntactical functions of self-aware consciousness, such as the perception of harmony and improvisation in music (

124,

125), depend on the maturity of the late-myelinating terminal association areas in prefrontal, inferior temporal, and inferior parietal cortex (

126,

127). Accordingly, patients are encouraged to practice integrative sensory awareness exercises regularly in a wide variety of their daily activities to promote the perception of unity and connectedness while acting spontaneously, as well as to reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation.

The final meditation focuses on deepening awareness of one's outlook on life, which is the backdrop that colors a person's perceptions. The ability to shift outlook on situations or temporal viewpoint is a function of contextual “mental time travel” that depends on self-awareness (

124,

128). Enhanced awareness of one's outlook and its triggers helps a person become free of the momentum of past conditioning and attitudes, thereby facilitating self-transformation. Essentially the meditations provide exercises that instill calm and awareness of each of the three steps in thought. Each meditation helps in this process until a person is aware of all the steps in thought, which reduces his or her vulnerability to unnecessary conflict and dissatisfaction, as described in more detail elsewhere (

1,

112).

The practice of most psychiatrists and mental health professionals often permits only short visits and limited time for psychotherapy. The availability of materials such as the Know Yourself course and assessment methods such as the TCI can help to enhance what clinicians can do in their office and help patients by having access to materials that intensify and elevate their clinical experience. We welcome communication and suggestions about how we can further assist you to incorporate a person-centered approach to well-being in your own clinical work.