Literature documenting the association between psychotogenic drug use and psychotic disorders is now rather extensive.

1–9 However, disagreement remains as to whether drug use can result in an autonomous psychotic disorder.

10–12 Whether or not drug use can induce or facilitate the emergence of chronic schizophrenia-like disorders is an important question with obvious research, clinical, and funding implications.

13,14 Establishing an etiologic relationship between drug use and the development of a chronic psychotic disorder is a difficult task.

15–17 Once a chronic psychotic syndrome starts, it is almost impossible to decide whether a particular patient was destined to develop the disease without substance abuse playing any role or whether substance abuse may have caused the disease to emerge in a person who otherwise would have never developed such a disease. It is, of course, also quite possible that a patient with low-level genetic loading for schizophrenia may manifest the disorder only after exposure to the toxic effects of drugs of abuse.

18,19 Clinical symptomatology overlaps a great deal between idiopathic and drug-induced psychosis.

20–22 Furthermore, a high proportion of patients with schizophrenia lack family history of the disorder,

23 which further increases the difficulty in differentiating between those with a genetically determined disease and those in whom environmental factors (including substance abuse) may have played a significant role either in causing the disorder or allowing it to emerge.

METHODS

The state of Connecticut prepares an annual state report including number of state mental hospital admissions and discharges categorized by age, gender, and admission diagnosis. The reports for the three Connecticut state mental hospitals were examined, and tables were made for all first admissions to any of the three facilities under the categories of drug abuse, schizophrenia or paranoid disorder, and affective disorder. The state reports contained a separate category for alcohol-related admissions. Although chronic alcohol use and withdrawals are known to contribute to the development of psychotic symptoms, the focus of this study was restricted to examining the relationship between illicit drug use and the development of chronic psychotic syndromes. Substance abusers with alcohol as their substance of choice were therefore not included in the study. The number of first admissions for drug-related problems was taken as an indirect measure of drug use by the general population during the period of the survey. Drug-related admissions were not categorized according to drug of choice (with the exception of alcohol).

The survey included the years 1965 through 1983. This period starts prior to the beginning of the drug use epidemic of the late 1960s and early 1970s and extends 10 to 12 years after the peak of the epidemic.

26 This is the window of time during which a peak in psychosis admissions would be expected if it were related to the drug use epidemic. All entries were for patients without prior hospitalization to any Connecticut state inpatient facility. Each entry included admission diagnosis, age, and gender. Ages were then grouped into three main categories: 15 to 24, 25 to 34, and 35 to 44. The span of the youngest age group varied, starting with age 15 for the first 5 years and age 18 for the last 5 years of the survey. Data were analyzed as absolute numbers as well as percentages of the number of total admissions per year of survey.

RESULTS

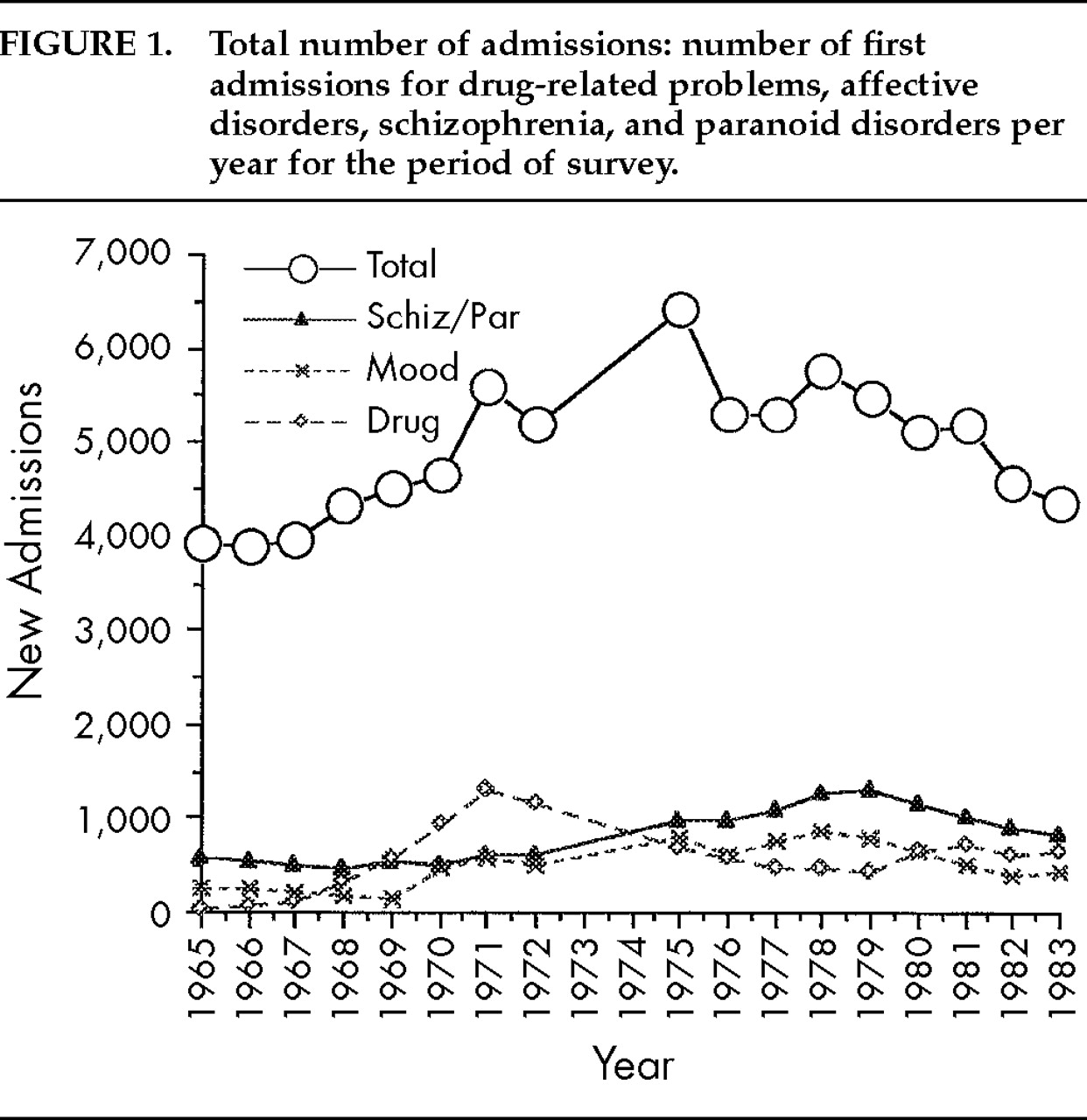

Figure 1 shows the total number of admissions, the number of first admissions for drug-related (abuse or dependence) disorders, affective disorders, and schizophrenia and paranoid disorders per year for the period of the survey.

The number of total admissions was stable in the first 3 years of the survey period (1965–1967). This stable period was followed by a period of steady increase of the number of total admissions, lasting through 1976. A period of stability then lasted until 1981, with some decline in the number of total admissions in the last 2 years of the survey.

The early increase in total admissions (1968–1971) seems to coincide with the increase in drug-related admissions. The continued increase in the number of admissions between 1971 and 1981 can at least be partially explained by the increase in the numbers of new cases of psychosis (schizophrenia and paranoia) and affective disorders admissions, which were offset by the simultaneous decrease in the number of drug-related new admissions.

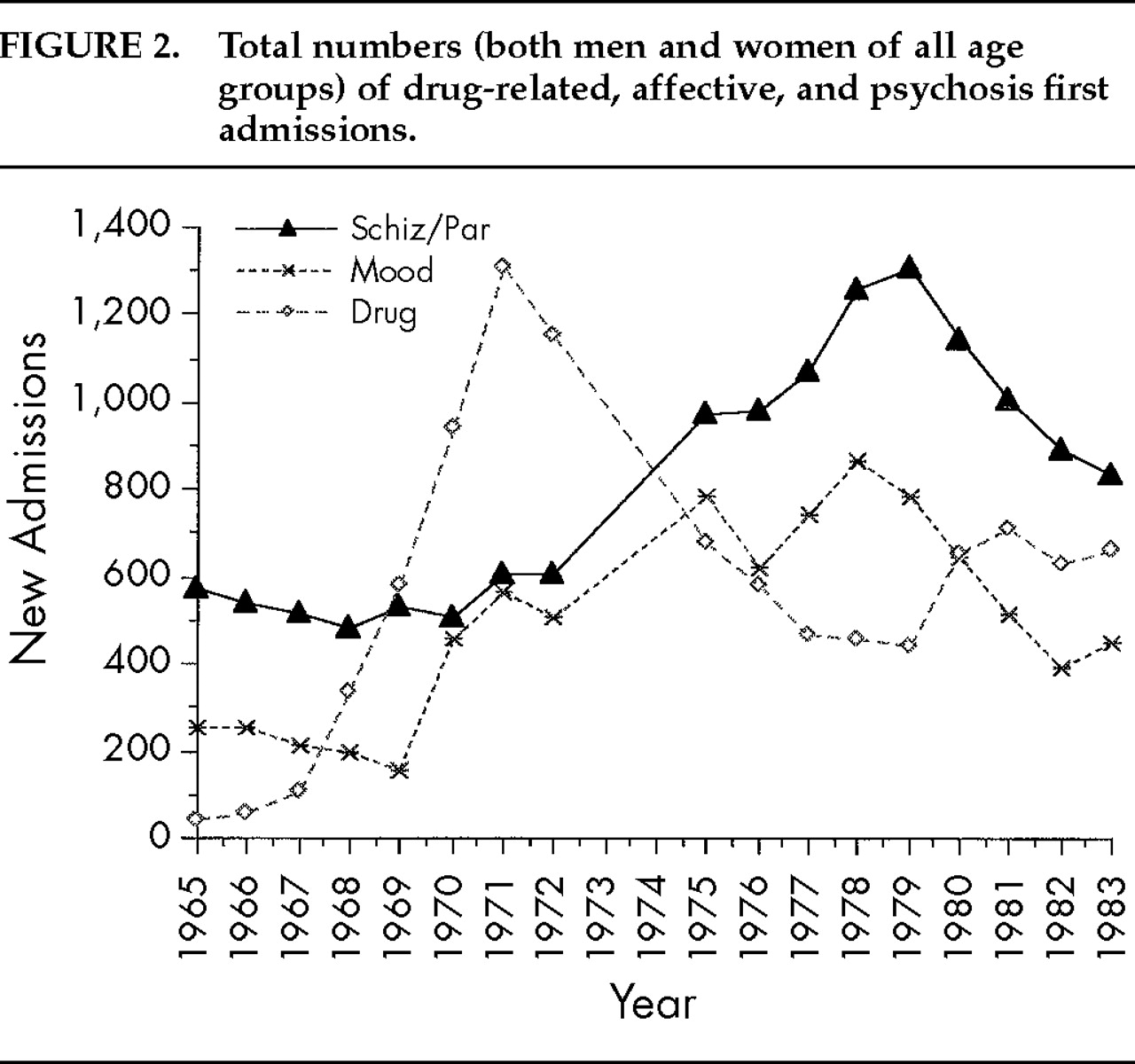

Figure 2 reproduces the bottom part of

Figure 1 and includes the curves for the total numbers (both men and women of all age groups) of drug-related, affective, and psychosis first admissions. As seen from the graph, the number of drug-related new admissions was rather low at the beginning but steadily escalated beginning in 1967 and reached its peak in 1971. A steady decline followed until 1979, followed by a more modest increase in the last 4 years of the survey.

The curve representing new admissions with paranoia or schizophrenia diagnoses shows remarkable stability in the first 6 years of the survey. This period of stability was followed by a period of rapidly escalating numbers of newly admitted psychotic patients. This period of escalation ended in 1978 and was followed by a constant decline until the end of the survey period; however, new admissions remained significantly higher than the baseline rate of the first 6 years of the survey.

The affective disorder curve paralleled the paranoia/schizophrenia curve, with an early stable period (1965–1969) followed by rapid escalation (1970–1978) and ending with a period of steady decline, but also remaining higher than the base rate of 1965–1968.

Correlation coefficients were calculated for the three groups of data (drugs, psychosis, affective). No correlations were found between the drug-related total admissions and psychosis or affective disorders data. On the other hand, the affective disorders admissions correlated significantly with the number of schizophrenia/paranoia admissions (r=0.849, df=17, P<0.0001).

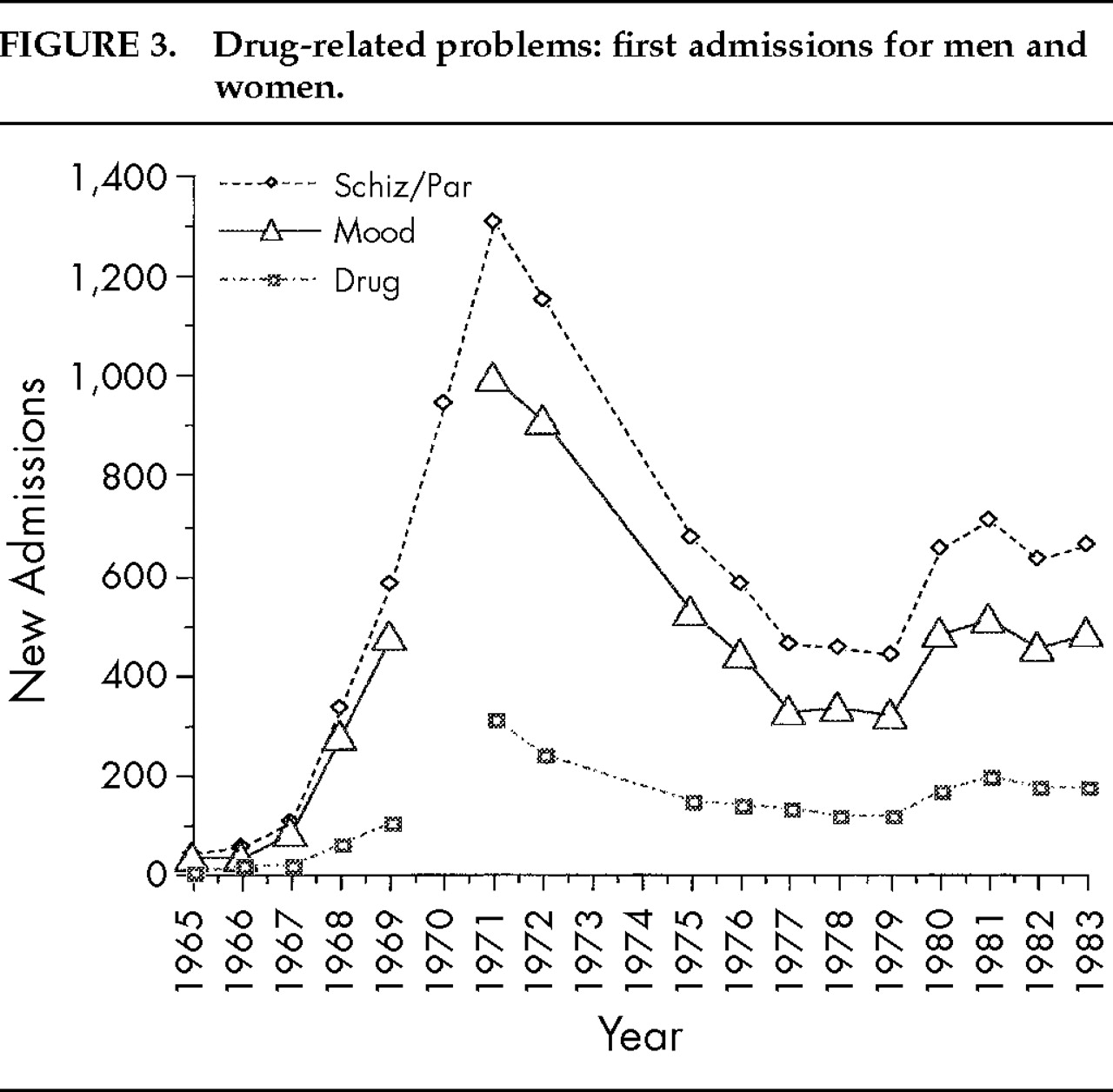

Figure 3 shows the breakdown of the number of drug-related first admissions for men and women. (Breakdown data are missing for 1970.) As can be seen from the graph, drug use increased in both men and women, but remarkably so in men.

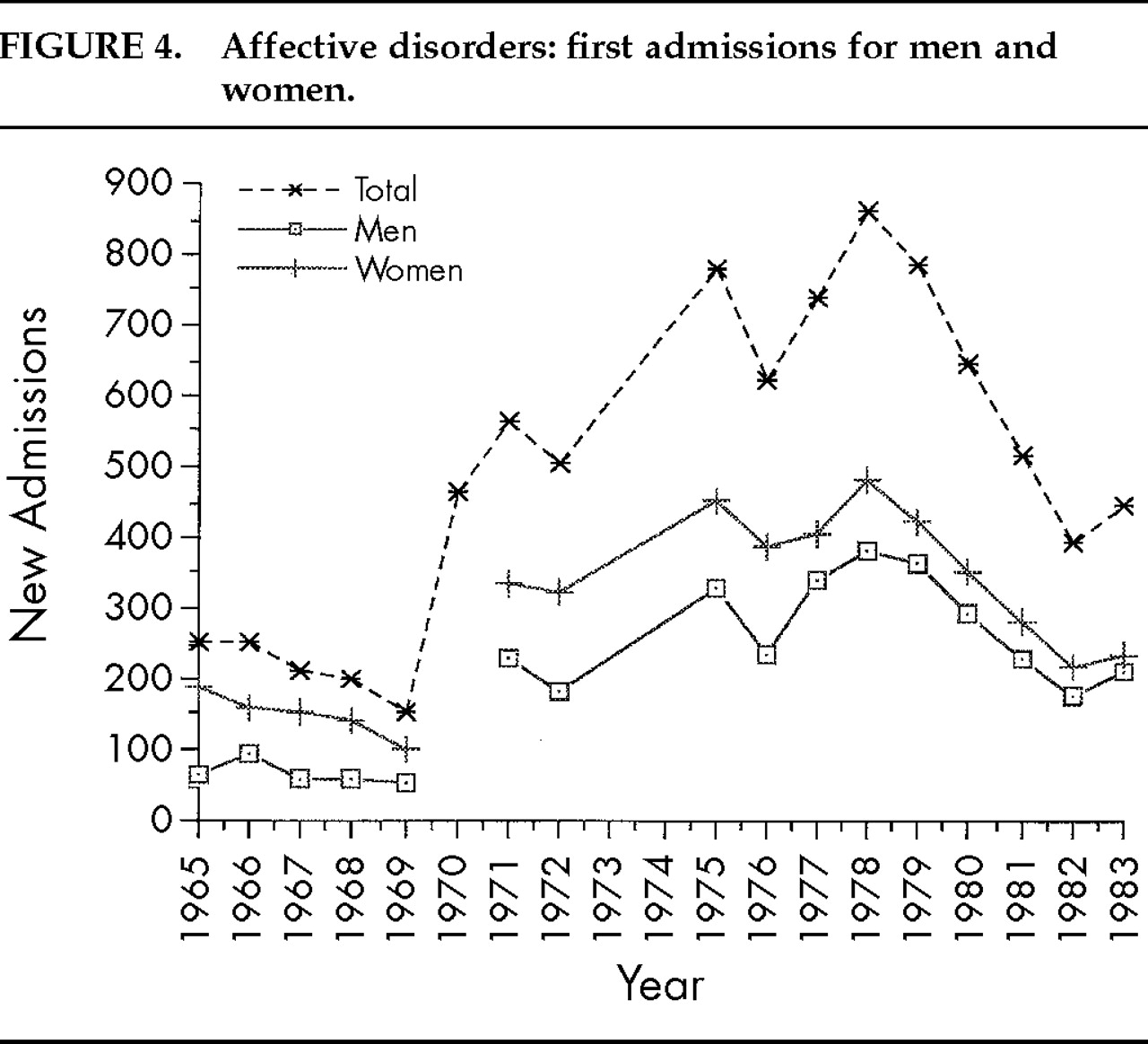

Figure 4 shows a similar graph for the affective disorders. The increase in mood disorders affected both men and women, but women were more represented in every year of the survey.

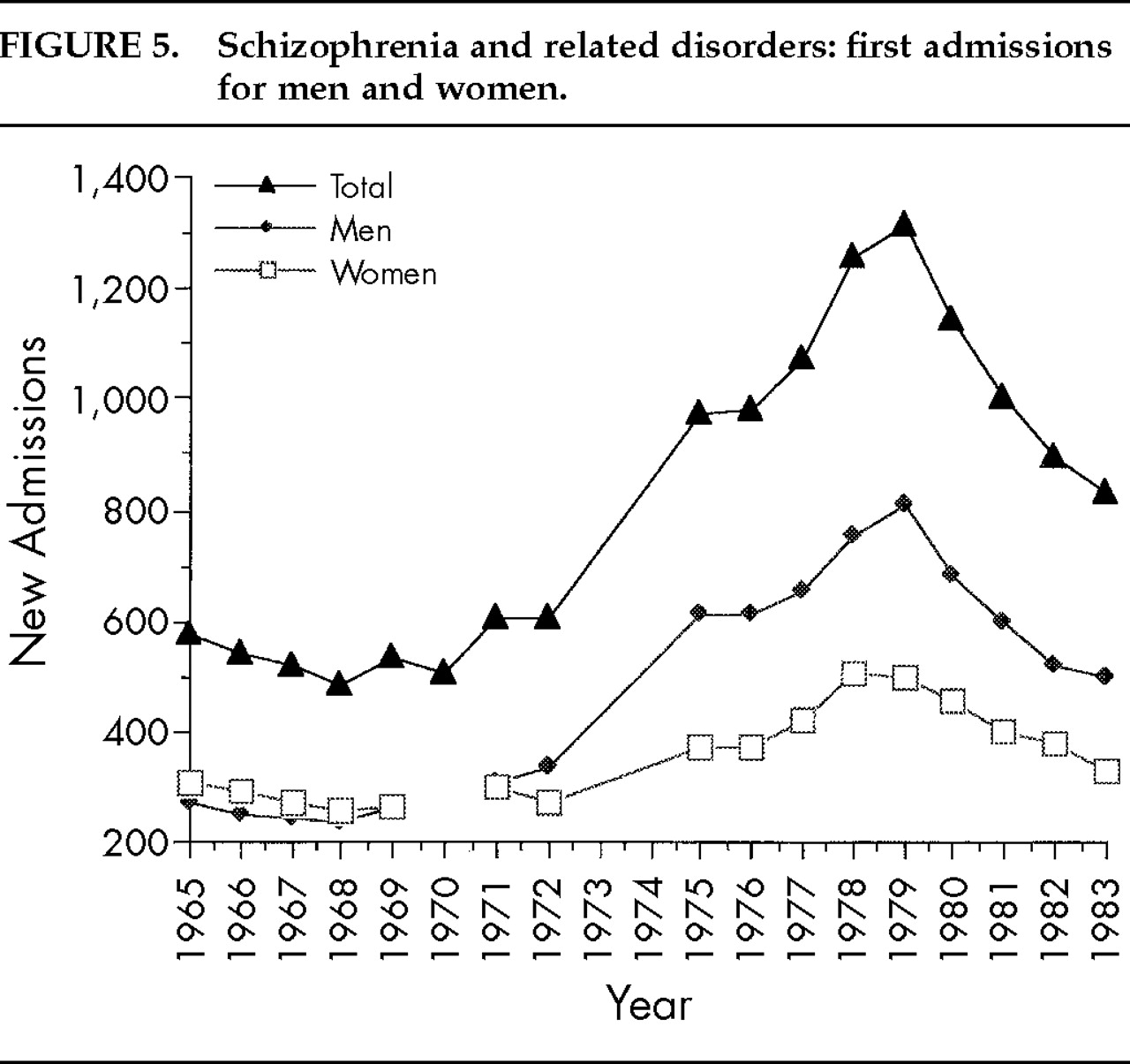

Figure 5 shows the distribution among men and women of psychosis-related new admissions. This graph also begins with a stable period during which women consistently outnumbered men (1965–1968). In both 1969 and 1971 the numbers became equal (1970 data missing). Starting in 1972, men progressively and consistently outnumbered women in this admissions category.

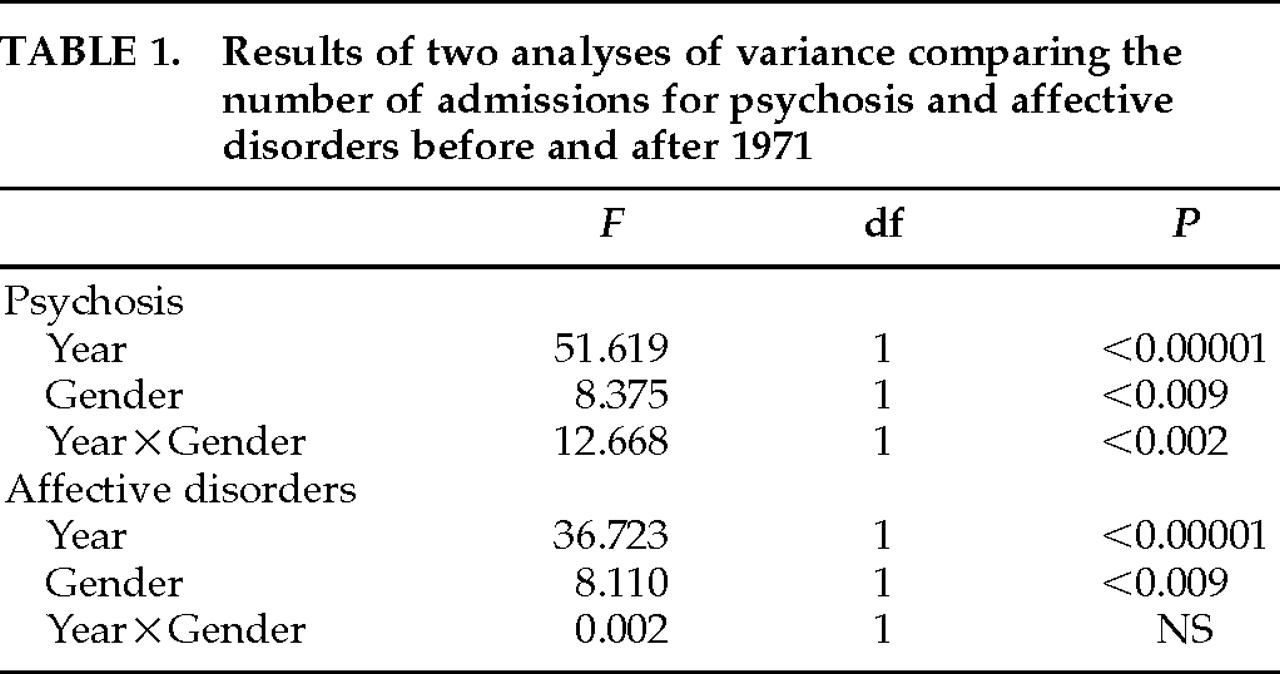

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for the number of new psychosis admissions (men vs. women) for the 6 years leading to the peak drug use year (1971) compared with the 10 years following 1971. A similar ANOVA was performed for the affective disorders admissions. The results of these two ANOVAs are presented in

Table 1. The ANOVAs show a highly significant increase in the number of psychosis and affective disorders admissions after 1971. The increase in schizophrenia/paranoia was predominantly due to an increase in male admissions. A significant year×gender effect was found for schizophrenia/paranoia but not affective disorders admissions (

Table 1).

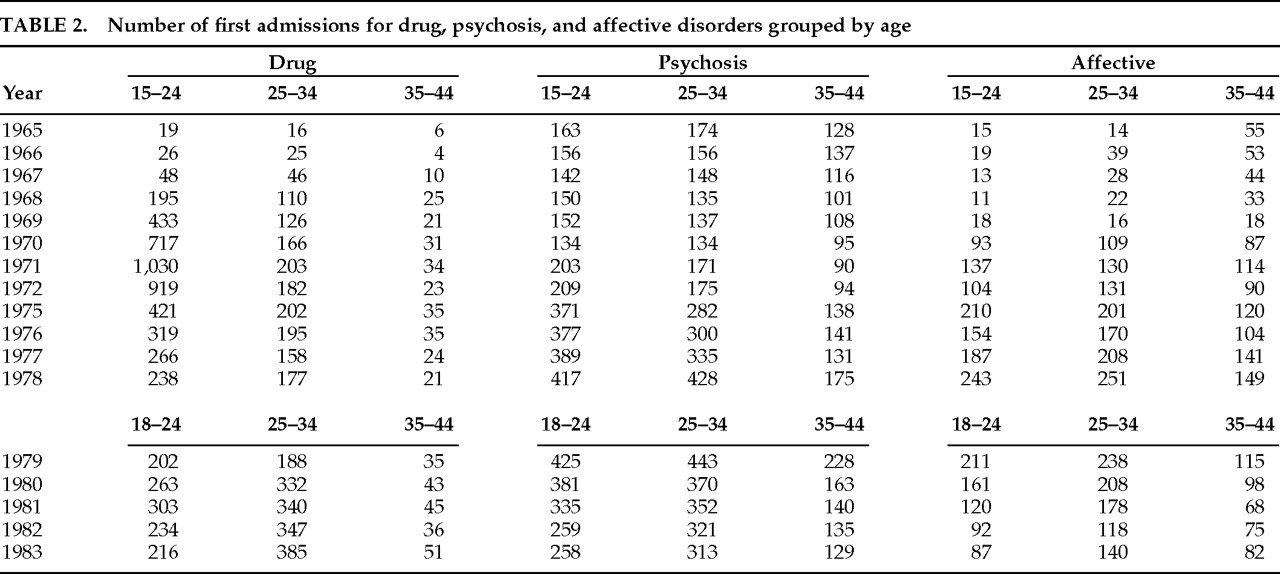

Finally, data were also examined according to age groups (15–24, 25–34, 35–44).

Table 2 shows the number of first admissions for the drug, psychosis, and affective disorders admissions. Drug-related admissions were mainly due to the 15–24 group, with the 25–34 group showing steady increase over the entire survey time and indeed surpassing the 15–24 age group in 1980 and the following years. The 35–44 age group remained largely at the same low level throughout the survey period. The increase in admissions for affective disorders was noted in all age groups, but more so in the younger patients (15–34). The differences between the age groups are not nearly as remarkable as with the drug-related admissions. On the other hand, the increase in paranoia/schizophrenia admissions was predominantly in the two younger age groups.

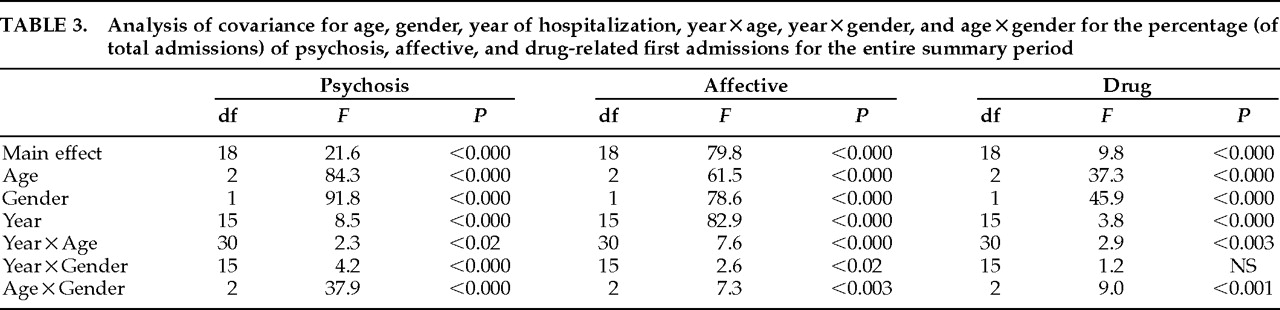

Many problems exist with relying on the raw numbers of admissions. Non–disorder-related factors (political or economic) may have influenced the rate of admissions of different groups of patients differently. The age range of the youngest patient group also varied. In order to eliminate the possible influences of these factors, the data were converted to proportions of total admissions for each year. Examination of the distribution of these proportions showed a nearly normal shape with no significant departures from normal, allowing for use of ANOVA statistics. An analysis of covariance was computed on the data for age and year with gender and gender×year as covariates. The results of the ANOVA are given in

Table 3. As seen from

Table 3, all three groups showed highly significant main effects for age, gender, and year. Significant age×year and age×gender interactions were seen in all groups. Significant year×gender interactions were seen only in the schizophrenia and affective disorders groups. There was no gender×year interaction in the drug group, which was consistently dominated by males.

DISCUSSION

These data are consistent with the interpretation that in the late 1960s in Connecticut a large increase in drug abuse patients was observed among first admissions to state hospitals, followed in 3 to 5 years by a substantial increase in first admissions of patients diagnosed with psychotic or mood disorders. Further, the data show that this increase was age- and gender-specific, particularly for schizophrenia and paranoid disorders.

The strong correlation between the affective and schizophrenia/paranoia admissions suggests that the admission rates of these two disorder categories were influenced by similar factors. The lack of correlation between the affective and the schizophrenia/paranoia admissions on one hand and drug-related admissions on the other suggests that the increased admissions rates were not the result of a general policy of increasing hospitalization of psychiatric patients or other general societal effects.

Three main lines of evidence support our hypothesis that the epidemic of drug use of the late 1960s and early 1970s contributed to the increase in schizophrenia/paranoia and affective disorders admissions noted in the mid to late 1970s. First, the highly significant difference between the rates of hospitalization before and after the drug-related admission peak strongly suggests that the epidemic of drug use of the late 1960s and early 1970s contributed to the emergence of new cases of schizophrenia, paranoia, and mood disorders. Second, the significant year×gender interactions seen in both schizophrenia/paranoia and affective disorder admissions reflect the increased male contribution to these increases. This finding further links these increases to the male-predominant earlier drug use peak. Indeed, in the schizophrenia/paranoia group there was a reversal of pattern of gender distribution preceding and following the drug use peak. This difference was significant whether the absolute number of admissions or the percentage of total admissions represented by admissions in each category was examined. The gender effect was not as striking for admissions related to affective disorders. Increased male contribution to this group was evident only when data were analyzed as percentages of total admissions (

Table 3). This observation is particularly notable. If indeed the increase in admissions was related to earlier drug use, the difference in gender effect may reflect a fundamental difference in the etiologic relationship between drug use and schizophrenia-like syndromes on the one hand and mood disorders on the other.

The third line of evidence linking the increase in schizophrenia/paranoia and affective disorders admissions to the earlier drug use epidemic comes from the age distribution. In the three diagnostic groups, the two younger age groups contributed more to the increase in admissions during peak years. In the schizophrenia/paranoia group, the percentage of new admissions in the age group 35–45 was significantly lower during the late 1970s schizophrenia admissions peak as compared with the first 6 years of the survey. In the mood disorders group this effect was more dramatic. During the first 4 years of the survey, preceding the period of increased drug use, the percentage of newly admitted patients in the 35–45 age range was highest. This trend was reversed following the drug use peak, with significant increase in the percentage of patients in the two younger age groups.

To summarize, the highly significant change in the rate of new admissions for the diagnosis of schizophrenia/paranoia and for affective disorders following a period of increased drug use by the community (as reflected by increased admissions for drug-related problems) suggests a chronological association between these observations. The age- and gender-related observations suggest that a factor that is strongly male predominant and that mainly affects younger individuals may have contributed to the increases in new admissions related to schizophrenia/paranoia and affective disorders during the late 1970s in Connecticut state hospitals. It seems likely that this phenomenon played a role in the emergence of the so-called young adult chronic patient.

27A change in the general admissions policy or a general increase in Connecticut population could contribute to trends similar to the ones reported here. Neither factor seems likely to have contributed to our observations. Connecticut population tended toward a constant decline during and after the period of the survey. Admission policies during the 1970s tended to lean more toward deinstitutionalization. The nature of the study, however, is such that other possibly contributing factors such as insurance policies and availability of private hospital beds could not be examined.

This study has a number of limitations. Because all subjects entered into the study were first admissions, the increased number of schizophrenia/paranoia or affective disorder patients admitted from 1970 onward could not be the same individuals admitted in the previous years (1966–1971) for drug-related problems. Our drug-related admission data can only be used as an indicator of the increased drug use problem in the community in general at that period of time. Although we were unable to provide independent epidemiological data to confirm drug use trends in the state of Connecticut, this period of time (late 1960s and early 1970s) coincides with a period of increased drug use nationwide.

26 A second limitation is that admissions were coded for the main diagnosis only. Comorbid conditions were not included in the survey. This is particularly important because many of the drug abusers may have also abused alcohol. Finally, the survey period spans more than one diagnostic system period (DSM-II and DSM-III).

28 In the same vein, admission diagnoses were made by different clinicians, potentially allowing for a large variability in the diagnostic criteria applied. Data analysis was limited by the data collected by the state at the time (for example, admission diagnosis versus discharge diagnosis). Given the recent DSM-IV nosology, some of the patients, especially those admitted in later years for psychosis or affective disorders, could have potentially been classified as “dual diagnosis” patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for “Psychotic or Mood Disorders Secondary to Substance Abuse.”

29The data nevertheless suggest that drug use has created new cases of psychosis and related disorders. Similar conclusions can be drawn from a Veterans Affairs study by McLellan and his colleagues where patients originally diagnosed as stimulant or hallucinogen abusers required repeated hospitalizations and received psychotic diagnoses in subsequent years.

15 In order for the case to be made that drug use can indeed induce new cases of autonomous psychosis or mood disorders, cases with varying degrees of genetic loading of the disease appearing after drug use should be followed for an extended period of time (perhaps 5–8 years) with measures instituted to ensure that no continued drug use has occurred. If a significant inverse correlation between the degree of genetic loading and the degree of recovery exists, the case may then be made that the symptoms were to a significant extent secondary to persistent drug effects.