Much clinical and basic science evidence indicates the involvement of frontal lobe, basal ganglia, and related neuronal connections in HIV-seropositive individuals.

1–15Frontal lobe, mainly the prefrontal cortex, has a specialized role in working memory (WM) processes.

16–19 WM is a complex memory system that supports higher cognitive functioning and therefore enables us to perform complex cognitive skills; on the basis of behavioral, neuropsychological, and functional neuroimaging data, three different WM systems—verbal WM, spatial WM, and object recognition WM—have been characterized.

20A few neuropsychological studies have evaluated WM in HIV-infected individuals, and all of them found working memory impairment only in symptomatic subjects.

21–23 These findings are in agreement with overall neuropsychological data relative to HIV infection, which indicate a significant proportion of symptomatic subjects are compromised in their cognitive functioning. However, a substantial number of studies found that a subsample of asymptomatic individuals may have mild to moderate impairment in memory, information processing speed, and some other specific cognitive areas that are independent of other confounding factors (such as depression or history of head trauma) and are in some cases significant predictors of mortality.

24 Furthermore, asymptomatic subjects without evidence of immune compromise do not appear to be at greater risk of cognitive impairment than HIV-negative control subjects, whereas for those HIV-infected individuals who are immune-compromised (even while asymptomatic), there seems to be increased risk of neuropsychological impairment.

25To the best of our knowledge, no study exists in the literature assessing the spatial component of WM in the course of HIV infection. In the present study we focused on the neuropsychological evaluation of spatial WM in a group of asymptomatic HIV-infected subjects as compared with a sample of age- and sex-matched seronegative control subjects; we enrolled only asymptomatic subjects, with the aim of assessing whether HIV could result in dysfunction in spatial working memory even in the asymptomatic phase of the illness.

METHODS

Subjects

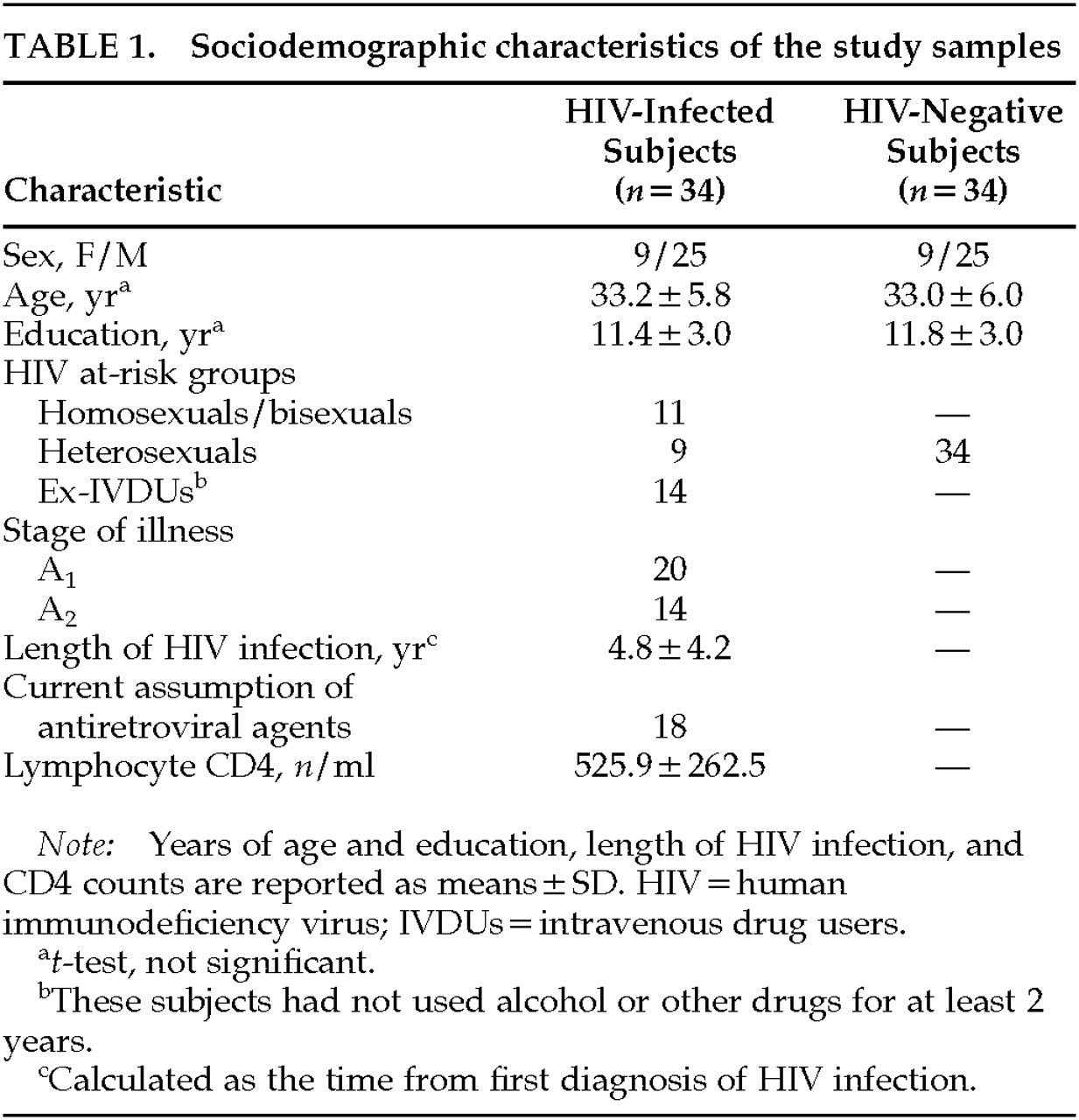

Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study samples. Thirty-four asymptomatic HIV-infected subjects (i.e., belonging to stages A

1 and A

2 according to the AIDS surveillance case definition for adolescents and adults, 1993

26) and 34 age- and sex-matched seronegative control subjects were enrolled in this study. Subjects' serostatus was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with Western blot confirmation of positive results. Subjects were recruited from the Infectious Diseases Department of San Raffaele Hospital (Milan, Italy); control subjects were recruited from hospital personnel. Subjects gave their consent to the study after all the procedures were fully explained.

Exclusion criteria were a personal history of psychiatric and/or neurological disorders, head trauma, learning disability, or recent alcohol and drug abuse. As a part of the enrolling procedures, subjects were administered the 21-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D) and 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS); subjects who gained a Ham-D score ≥10 and/or a BPRS score ≥21 were excluded from the study.

All subjects were right-handed, handedness having been assessed by means of the Raczkowsky questionnaire.

27Procedures

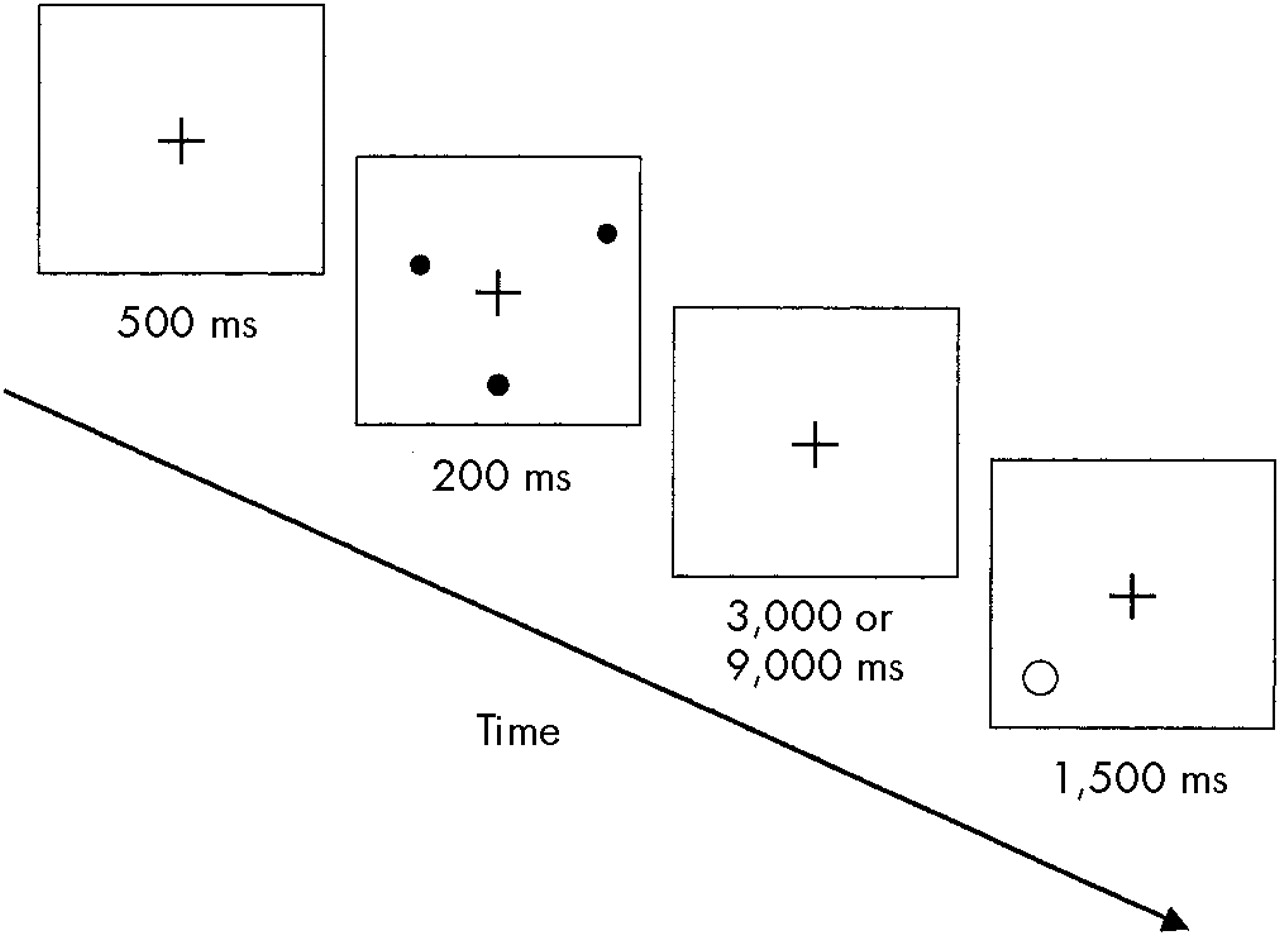

Figure 1 shows the experimental procedure (modified) that we used to assess spatial WM.

28 The subject begins by fixating a cross in the center of a computer screen for 500 milliseconds; then, three randomly arrayed dots on the circumference of an imaginary circle centered on the cross appear, which remain on the screen for only 200 ms. A retention interval of 3,000 or 9,000 ms follows, during which the subject has to keep in mind the spatial location of the three dots. At the end of this interval, a location probe appears on the screen, consisting of a single circle that either encircles the location of one of the previous dots or does not. The subject's task is to press a key with the dominant hand if the probe encircles the location of a target dot or with the nondominant hand if it does not. The probe circle is either centered directly on the location of a previously presented dot or it misses the nearest dot location by 40 degrees; the subject has to give an answer within 1,500 ms. After the subject presses the key, a new sequence with different point location starts and the entire procedure is repeated.

Prior to the evaluation, each subject was given verbal instructions together with a single training session during which subjects were consecutively administered 10 tests. Subjects were judged to be well trained if they were able to correctly repeat and carry out the verbal instructions and if the total number of errors was less than 3. At the end of these training sessions all subjects were convincingly well trained, and none was excluded.

During the evaluation, subjects were first administered a set of 20 consecutive tests, each characterized by a retention interval of 3,000 ms, and then a second set of 20 consecutive tests, each characterized by a retention interval of 9,000 ms. Mean number of errors and mean response time for each subject were computed for the two sets of tests.

Digit Span test was administered to subjects in an attempt to ensure cognitive comparability between the two groups; no differences were recorded between seropositive individuals and control subjects (Mann-Whitney U-test: P=0.452).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov procedure was used to test whether neuropsychological data were normally distributed; since this procedure showed that these neuropsychological data were not normally distributed, nonparametric tests were selected for data analysis.

Number of errors and response time of asymptomatic HIV-infected subjects versus seronegative control subjects were compared by means of Mann-Whitney U-tests, both in the 3,000-ms and the 9,000-ms retention interval paradigms. Furthermore, in the group of asymptomatic HIV-infected subjects, the same measures (number of errors and response time) were compared with respect to stage of infection (A1 vs. A2), presence of a past history of intravenous drug abuse (subjects with such a history vs. subjects without), and presence of antiretroviral medications (subjects on vs. not on antiretroviral medications) by using Mann-Whitney U-tests, both in the 3,000-ms and the 9,000-ms retention interval paradigms.

Subjects were divided according to the presence/absence of a past history of intravenous drug abuse and the presence/absence of antiretroviral medications. This was done because data in the literature indicate these factors as potentially confounding variables in the context of HIV-related neuropsychological studies.

29RESULTS

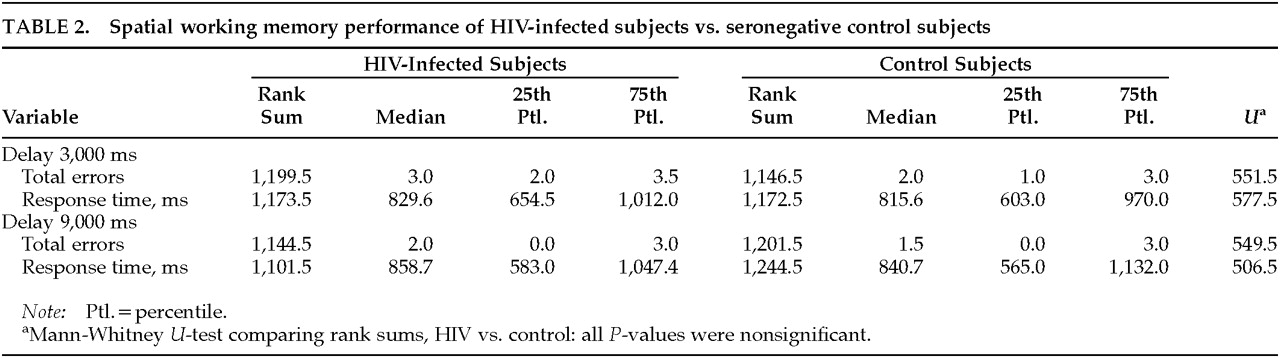

As shown in

Table 2, no significant differences were found in number of errors or response time when HIV-infected subjects and seronegative control subjects were compared, either in the 3,000-ms or the 9,000-ms retention interval paradigm; moreover, among the HIV-infected subjects, no significant differences were found on the same measures when subjects belonging to different stages of the infection were compared.

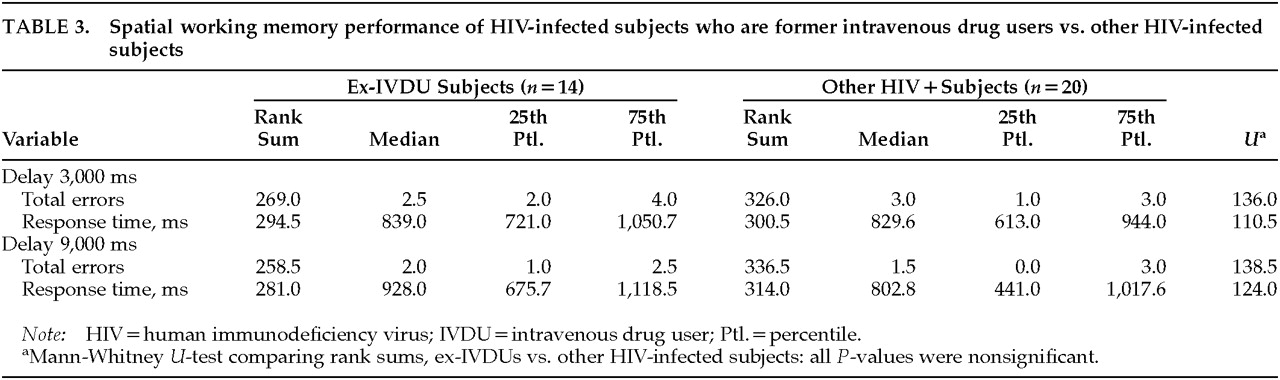

The presence/absence of a past history of intravenous drug abuse (

Table 3) and the presence/absence of antiretroviral medications did not influence the spatial WM performance of subjects, either in the 3,000-ms or the 9,000-ms retention interval paradigm.

Finally, no significant correlations were found between number of errors, response time and age, length of illness, and number of lymphocyte CD4.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the spatial component of WM in the context of HIV infection. Our findings do not show any spatial working memory impairment during the asymptomatic phase of HIV infection. These data suggest that although structural and functional frontosubcortical abnormalities may be found in HIV infection, they do not imply neuropsychological deficits relative to working memory during the early, asymptomatic stage of the illness.

Some authors of neuropsychological studies in the context of HIV infection have mentioned that there are potentially confounding variables, such as neurological or psychiatric disorders, head trauma, or drug abuse, that can eventually influence findings,

29 and it is therefore recommended that these variables be controlled for when performing data analysis. In this study, some of these variables were exclusion criteria and therefore were not confounders; furthermore, our data show no significant differences between subjects who are at different stages of the infection, between subjects with and without a past history of drug abuse, or between subjects on antiretroviral therapy and subjects free of such medications.