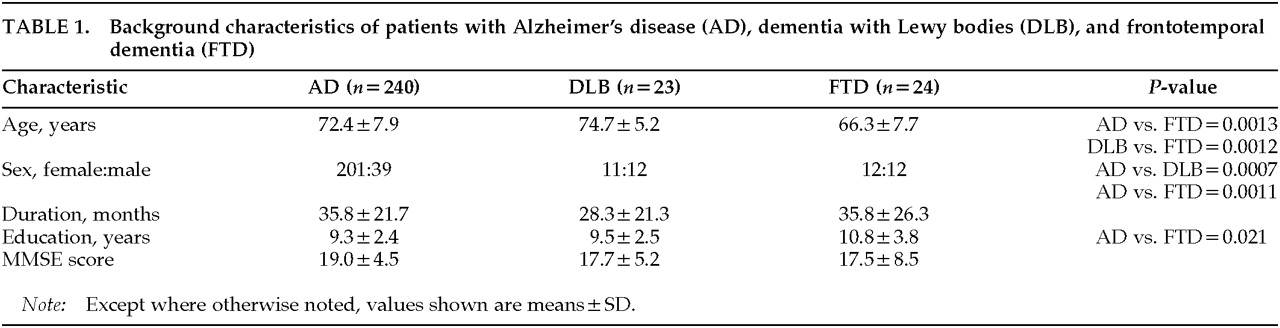

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in most industrialized countries,

1 and other types of neurodegenerative diseases are increasingly being recognized as important causes of dementia. Among them, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are reportedly the second and third most common pathologies and thus are the ones that must be most carefully differentiated from AD in choosing the appropriate treatment for patients.

2–9 DLB is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the presence of Lewy bodies in cortical and brainstem structures. In 1996, an international workshop recommended “Dementia with Lewy bodies” as a generic term and proposed criteria for clinical and pathological diagnosis.

8 FTD is characterized by peculiar behavioral changes arising from frontotemporal involvement. In 1994, the Lund/Manchester groups proposed clinical and pathological criteria for FTD.

9 According to these criteria, three types of histological change (Pick-type, frontal lobe degeneration type, and motor neuron disease type) underlie the atrophy, and there is preferential frontal and temporal lobar involvement in all three histological types.

Neuropsychiatric disturbances are common in these three most dementing illness. Elucidating their distinctive neuropsychiatric features can be effective not only for differentiating these diseases and choosing the appropriate neuropsychiatric management, but also for understanding the underlying mechanism of the behavioral symptoms. Neurobehavioral features of AD, DLB, and FTD have been described in the literature,

10–26 although prospective comparative studies with quantitative evaluation are scarce.

19,25,26 No study has been conducted that directly and quantitatively compares the neuropsychiatric disturbances of the three diseases. In the present study, to elucidate the distinctive neuropsychiatric features among AD, DLB, and FTD, we prospectively studied neuropsychiatric manifestations in patients with AD, DLB, or FTD by using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI),

27,28 an established comprehensive tool for assessment of behavioral abnormalities in dementia.

RESULTS

The total NPI scores of the three groups (mean±SD) were 16.4±13.2 for AD, 22.2±15.9 for DLB, and 16.4±16. 6 for FTD, respectively, and the group difference was not significant (

F=1.86, df=2,284,

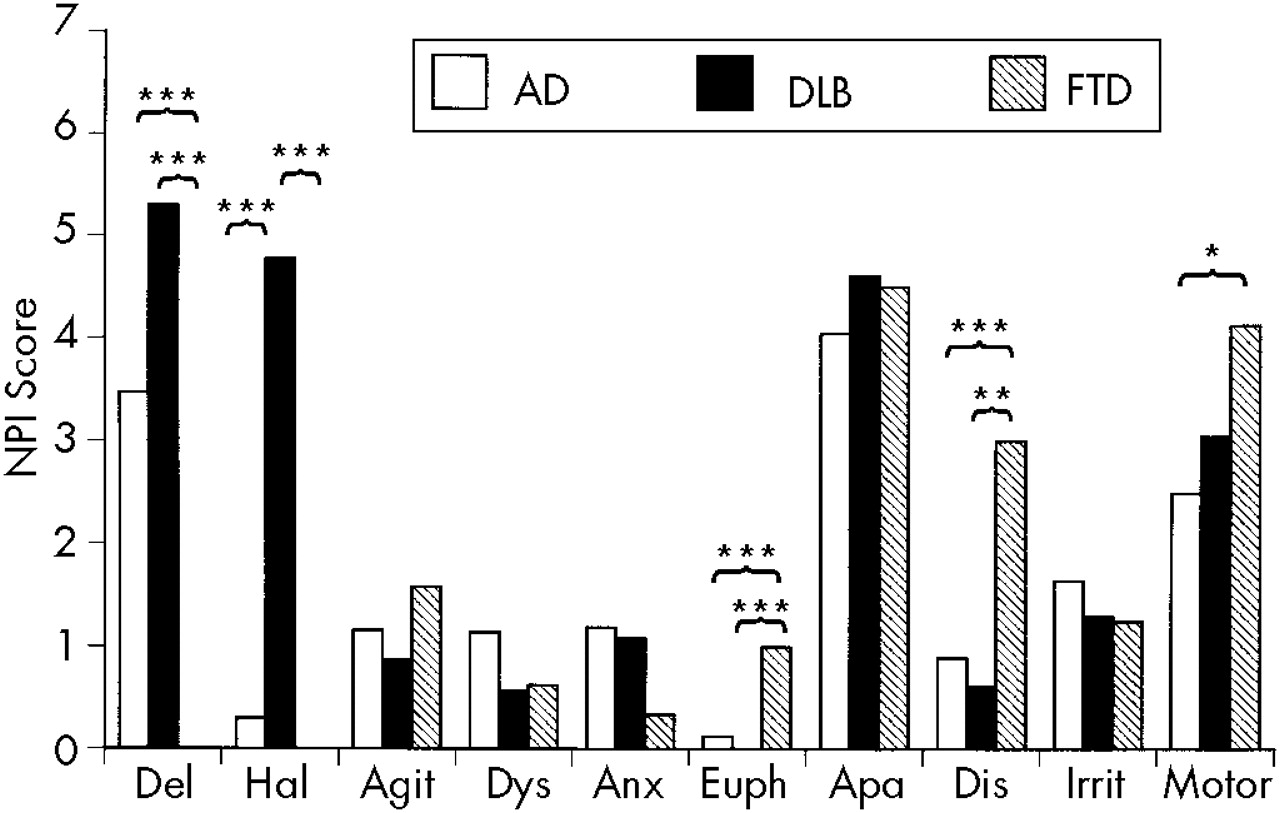

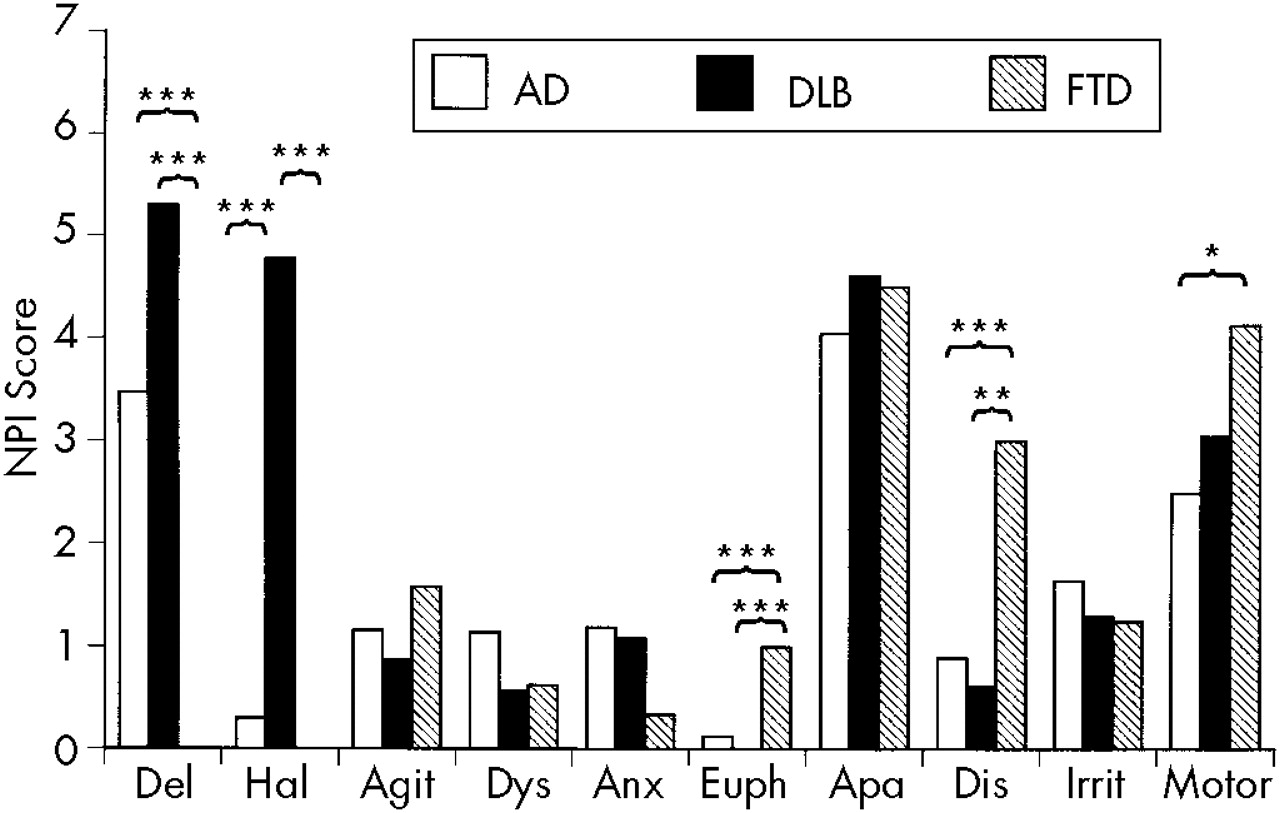

P=0.16). The mean scores of each NPI subset of the three groups are summarized in

Figure 1. One-way ANOVA revealed significant group differences for the delusion (

F=10.02, df=2,284,

P<0.0001), hallucination (

F=61.60, df=2,284,

P<0.0001), euphoria (

F=11.16, df=2,284,

P<0.0001), disinhibition (

F=7.43, df=2,284,

P=0.0007), and aberrant motor activity (

F=4.64, df=2,284,

P=0.01) scores. The post hoc Scheffé test demonstrated that the FTD group's NPI scores were significantly lower for delusion and higher for euphoria and disinhibition than were the AD and DLB groups' and significantly higher for aberrant motor activity than was the AD group's. The DLB group had a significantly higher hallucination NPI score than did the AD and FTD groups.

The frequency of each neuropsychiatric symptom (on a present/absent basis), is summarized in

Figure 2. Fisher's exact probability test revealed significant group differences for delusion (

P<0.0001), hallucination (

P<0.0001), dysphoria (

P=0.0086), euphoria (

P=0.048), and disinhibition (

P=0.0023). The post hoc Fisher's exact probability test with Bonferroni correction demonstrated that delusions were less common and disinhibition was more common in the FTD group than in the AD and DLB groups. As for the types of delusions, both persecutory delusions (delusions that people are stealing things, delusions that the patient is being conspired against or harassed, and delusions of abandonment) and misidentification delusions (delusions that someone is in the house, delusions that the house is not the patient's own house, and delusions that television figures are actually present in the home) were less common in the FTD group (0.0% and 0.0%) than in the AD group (41.3% and 24.6%) and the DLB group (43.5% and 78.3%). Misidentification delusions were more common in the DLB group than in the AD group. Hallucinations were more common in the DLB group than in the AD and FTD groups. As for the types of hallucinations, visual hallucinations were more common in the DLB group (69.6%) than in the AD (3.3%) and FTD (0.0%) groups. Auditory hallucinations were also more common in the DLB (13.0%) group than in the AD (4.6%) and FTD (0.0%) groups, although the difference was not significant. No patients showed other modalities of hallucinations. Dysphoria was more common in the AD group than in the FTD group.

In a stepwise discriminant function analysis, four NPI scores retained significant F-values: hallucinations (F to enter=61.60; Wilks' lambda=0.70), euphoria (F to enter=11.63; Wilks' lambda=0.64), delusions (F to enter=7.53; Wilks' lambda =0.61), and aberrant motor behavior (F to enter=5.99; Wilks' lambda=0.59). The final equation using these four variables correctly assigned 77.5% of the AD, 52.2% of the DLB, and 58.3% of the FTD patients to the correct diagnostic groups.

DISCUSSION

Several methodological issues limit the interpretation of the results of this study. First, the diagnosis relied solely on a clinical basis without histopathologic confirmation. There is a controversy about the accuracy of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop criteria

8 for differential diagnosis of DLB from AD. Mega et al.,

34 evaluating the accuracy of the criteria based on the clinical records of patients with pathologically verified AD and DLB, reported an acceptably high specificity (79%–100%) and a relatively low sensitivity (40%–75%), whereas Papka et al.

35 demonstrated a high sensitivity (88.9%) and low specificity of the criteria. The validity of the Lund/Manchester groups' clinical criteria for FTD

9 has not yet been established. Therefore, there remains a possibility that patients with a different disease contaminated each diagnostic group. Nevertheless, although clinical studies are in fact influenced by the quality of clinical diagnosis, clinical studies with prospective clinical data collection can assess patients' neuropsychiatric manifestations more accurately than can autopsy studies with retrospective data review. Moreover, we supplemented the clinical diagnosis with neuroimaging studies. In addition, the presence of visual hallucinations is included in the criteria for probable DLB,

8 and disinhibition and stereotyped and perseverative behaviors are included in the core diagnostic features in the criteria for FTD.

9 These may affect the apparent prevalence of these symptoms, and the effect should be discounted when interpreting the results.

Second, a large number of patients were included in the AD group and only one-tenth as many in the other groups. Although this unbalance was caused by a different prevalence of these diseases, the small size of the DLB and FTD groups gives a modest statistical power.

Third, repeated comparisons in the present study raise the likelihood of an experimental Type I error. Corrections for repeated comparisons were not made because of the exploratory goals of this study and concerns about a Type II error. We finally avoided this possibility by applying a multivariate discriminate analysis.

Fourth, some of the demographic characteristics were significantly different among the three dementia groups. For example, we previously demonstrated that the patients' age and sex were related to delusions and hallucinations in AD.

33 However, these different demographic characteristics were more likely to be caused by different disease properties than by a sampling bias. The duration of illness and the Mini-Mental State Examination score were at least comparable among the three disease groups.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings are quite reliable because they are based on 1) a consecutive patient series whose diagnosis was carefully made with widely accepted clinical criteria, and 2) an established comprehensive tool for the assessment of behavioral abnormalities.

Our results demonstrated that disinhibition, euphoria, and aberrant motor behavior were significantly more common and severe, and that delusions, hallucinations, and depression were significantly less common, in the FTD patients. Our findings were in agreement with previous comparative studies of AD and FTD,

20–26 although there has never been a direct comparison between FTD and DLB. Lewy et al.,

25 examining patients with AD and other patients with FTD with the NPI, noted that disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, euphoria, and apathy scores were significantly higher in the patients with FTD. They also noted that the depression score was lower in patients with FTD. Barber et al.,

24 in a study in which neuropsychiatric changes of patients with autopsy-proven FTD and AD were retrospectively examined by questioning their close relatives, found that patients with FTD were more likely to exhibit early personality changes such as disinhibition and socially inappropriate behaviors and less likely to exhibit delusions and hallucinations than were patients with AD. Gustafson

20 also noted that hallucinations were less frequent in the FTD patients than in the AD patients.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are reportedly very common in patients with DLB and are considered to be a central feature of this disease.

8,10–19 Our study quantitatively confirmed previous observations that most patients with DLB had visual hallucinations. Delusions and hallucinations in other sensory modalities, which are regarded as supportive features of DLB,

8 were reported to be significantly more common in patients with DLB than in patients with AD.

10,12,13,17 However, in the present study, the severity and frequency of delusions and auditory hallucinations in patients with DLB did not significantly differ from those with AD. More interestingly, a more distinctive difference between delusions in AD and delusions in DLB was the type of delusion: misidentification delusions, not persecutory delusions, were significantly more common in the patients with DLB than in those with AD. Ballard et al.

17 also reported that delusional misidentification was significantly more common in DLB than in AD.

These different patterns of neuropsychiatric features among diseases can be attributed to the different patterns of cerebral involvement. In FTD, there is a predominant involvement of the anterior cerebrum,

9,36,37 whereas posterior involvement predominates both in AD

38,39 and DLB.

40–42 Moreover, decreased occipital metabolism are disproportionately more severe in DLB than in AD.

40–42 Therefore, the features of behavioral abnormality in FTD (i.e., disinhibition and euphoria) are related to frontal involvement.

43 Although depression is also considered to be associated with frontal dysfunction,

32,43 this symptom was not common in FTD. This pattern can be explained by the way in which depression is defined by the NPI. The NPI depression items are designed to focus on mood changes

28 rather than on anhedonia or vegetative symptoms, although anhedonia with vegetative symptoms is generally, for example in the DSM-IV, weighted equivalently to mood changes for the diagnosis of major depression.

1 Feelings of sadness and melancholia will be concealed by apathy when frontal dysfunction is severe, as it is in FTD. On the other hand, delusions and hallucinations, which are more frequent in AD and DLB, involve the posterior cerebral region. Among the delusions and hallucinations, visual hallucinations and misidentification delusions were more common in DLB than in AD. Therefore, these manifestations may be related to occipital involvement, which is more severe in DLB than in AD. This hypothesis is supported by findings that unilateral or bilateral medial occipital ischemic lesions often produce agitated delirium,

44,45 which is mainly characterized by hallucinations and delusions.

46 Our previous study of delusions in AD,

47 which found a correlation between decreased relative regional glucose metabolism in medial occipital cortices and delusions, may also support this hypothesis.

In summary, AD, DLB, and FTD have different patterns of neuropsychiatric symptoms. The distinctive neuropsychiatric features may correspond to different patterns of cerebral involvement characteristic to these three major degenerative dementias. However, as there is considerable overlap, the utility of this finding in differential diagnosis on a case-by-case basis may be limited.