Psychosis, characterized by delusions and hallucinations, develops in approximately one-third of patients and is considered one of the most serious complications of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

1–3 There have been several studies of the prevalence of delusions in AD, with estimates ranging from 16%

4 to as high as 73%.

5 Hirono et al.

6 reported that 51.5% of their 228 AD patients showed evidence of delusions or hallucinations, with the vast majority of these patients (80%) experiencing delusions only. Teri et al.

7 reported that AD patients with behavioral problems declined at a rate 1.4 to 5 times faster than AD patients without such problems. Psychosis appears to predict cognitive as well as functional decline in AD, but its relationship to increased mortality remains unclear.

8,9Although some reports noted that behavioral disturbances in AD were associated with the later stages of the disease,

10,11 there is recent evidence that psychiatric disturbances may appear at any stage of illness severity in AD patients.

12–14 The relationship between gender and psychosis in AD is mixed: some studies report higher prevalence in females,

2 whereas in other studies males were more likely to exhibit delusions.

4 Age, duration of illness, cognitive level, or genetic markers such as apolipoprotein E have not demonstrated consistent associations with psychosis in AD.

15 However, there is increasing evidence to support an association between extrapyramidal disease and psychiatric complications in AD.

16–18Extrapyramidal signs (EPS), including rigidity, bradykinesia, and masked facies, are found in 10% to 30% of patients meeting clinical criteria for AD, and there appears to be a consensus that the presence of EPS is associated with a more rapid progression of dementia (see review

19). Parkinsonism has been known to coexist with AD for some time,

19 yet its prevalence in AD does not appear to be influenced by either dementia severity or illness duration.

The literature on neurobehavioral disturbances in AD strongly suggests that when they occur together, EPS and psychosis signal a poor prognosis.

17,20–22 Moreover, it has been reported that AD patients with EPS had twice the frequency of psychosis compared with AD patients without EPS.

23,24 Stern et al.

21 reported that AD patients with measurable EPS at intake reached significant functional and cognitive deterioration earlier than AD patients without measurable EPS at intake. Rosen and Zubenko

8 found that 60% of their AD patients with EPS developed psychosis at some time during the course of their illness.

These findings suggest that EPS and psychosis may share a common neurobiologic mechanism. However, the complex nature of putative basal ganglia circuits that give rise to both psychosis and EPS suggests the involvement of multiple circuits.

25–27 Identifying a pattern in the association between EPS and psychosis may lead to a greater understanding of potential neural circuit dysfunction in AD. The purpose of the present study was to examine specific associations between presence and severity of delusions and hallucinations and extrapyramidal dysfunction in AD.

METHODS

Patients

Fifty-two patients (37 males and 15 females) participated in this study. Patients were recruited from the University of California, San Diego, Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC) or the San Diego Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. The patients met the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) for probable AD.

28 The average age of the patients was 76.2±9.7 years. (All mean values herein are reported with standard deviations.) They had a mean illness duration of 4.5±3.1 years. Their mean total score on the Mini-Mental State Examination

29 (MMSE) was 20.6±5.0. None of the patients were currently taking neuroleptic medication, nor did any patient have a history of neuroleptic exposure. The purpose of the study was explained to the patients or their caregivers, after which an informed consent document was signed.

Instrumental Measures of EPS

Objective measures of EPS offer several advantages over traditional methods of rating movement disorders in AD.

30,31 Instrumental recordings of EPS yield continuous data, which are more linearly related to the behavior being studied than are the categorical data obtained from rating scales. Instrumental recordings are less susceptible to examiner experience or bias than observer ratings. Instrumental measures are sensitive to the presence of mild EPS and have been shown to detect EPS early in the course of antipsychotic medication in AD patients.

32,33In the present study, rigidity and bradykinesia of the upper extremities were assessed by use of electromyography (EMG). Disposable surface (patch) electrodes were placed over the wrist flexors of each forearm and a reference electrode was placed on the elbow. All data were acquired by using a portable 4-channel data logger designed by FlexAble System (Fountain Hills, AZ). The data logger has built-in 12-bit analog–digital converters, pre-amplification, and low-pass filters. Signals were stored online by using a notebook computer.

For the rigidity assessment, the background resting muscle activity was compared with the muscle activity during contralateral activation. Analyses were conducted offline by using waveform analysis software and involved computing the area under the curve of the integrated EMG waveform for the resting and contralateral activation tasks and obtaining the ratio of these values.

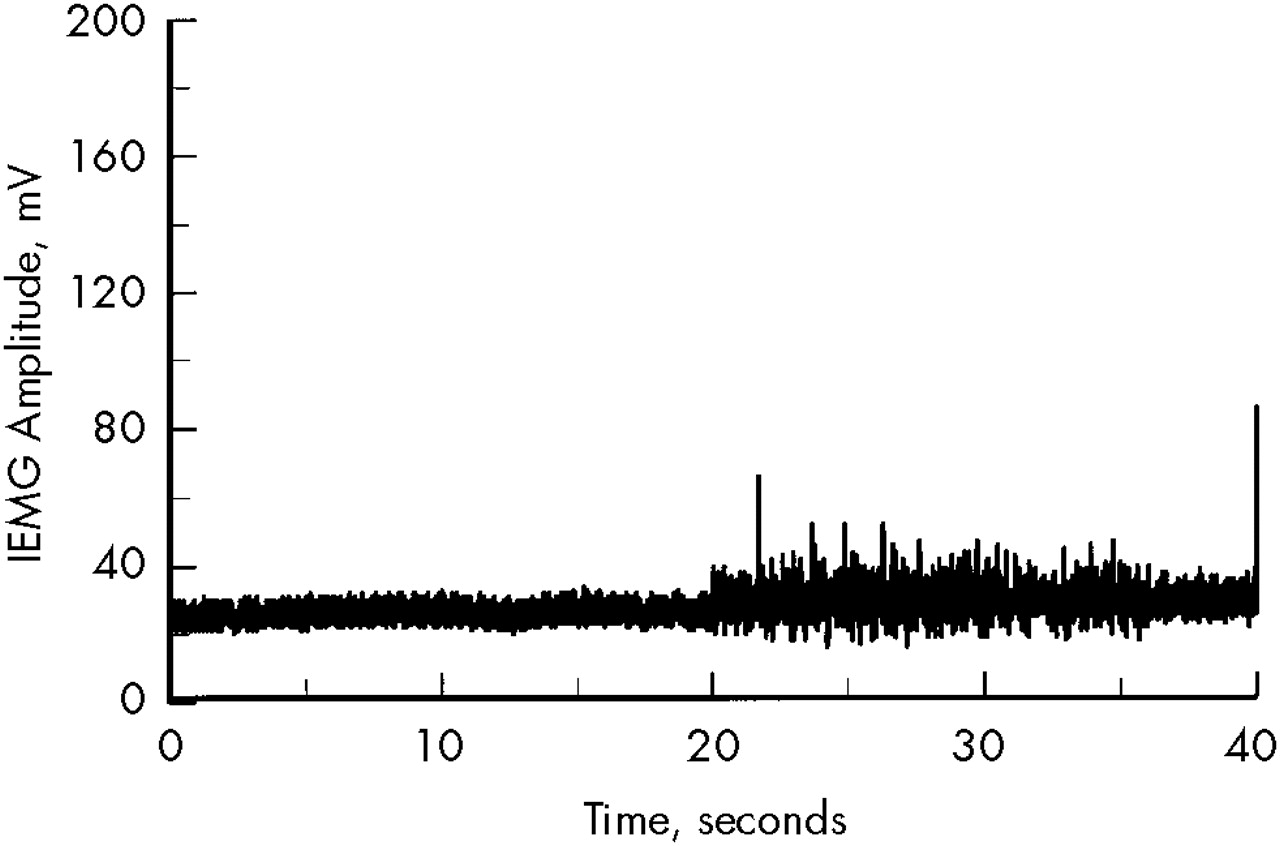

Figure 1 shows an example of an EMG trace of a patient with mild rigidity.

The first 20 seconds of the waveform were recorded during rest, the second 20 seconds during contralateral activation. Quantitative analysis of the increase in background EMG, using the integral technique, revealed an active/rest ratio of 1.26. This score is approximately 1.5 standard deviations greater than the normal mean (1.02).

For assessing bradykinesia, the subject was instructed to contract and relax the hand (by making a fist) repeatedly as quickly as possible for 5 seconds. It has been established previously that the amplitude of the EMG agonist burst is directly associated with movement velocity.

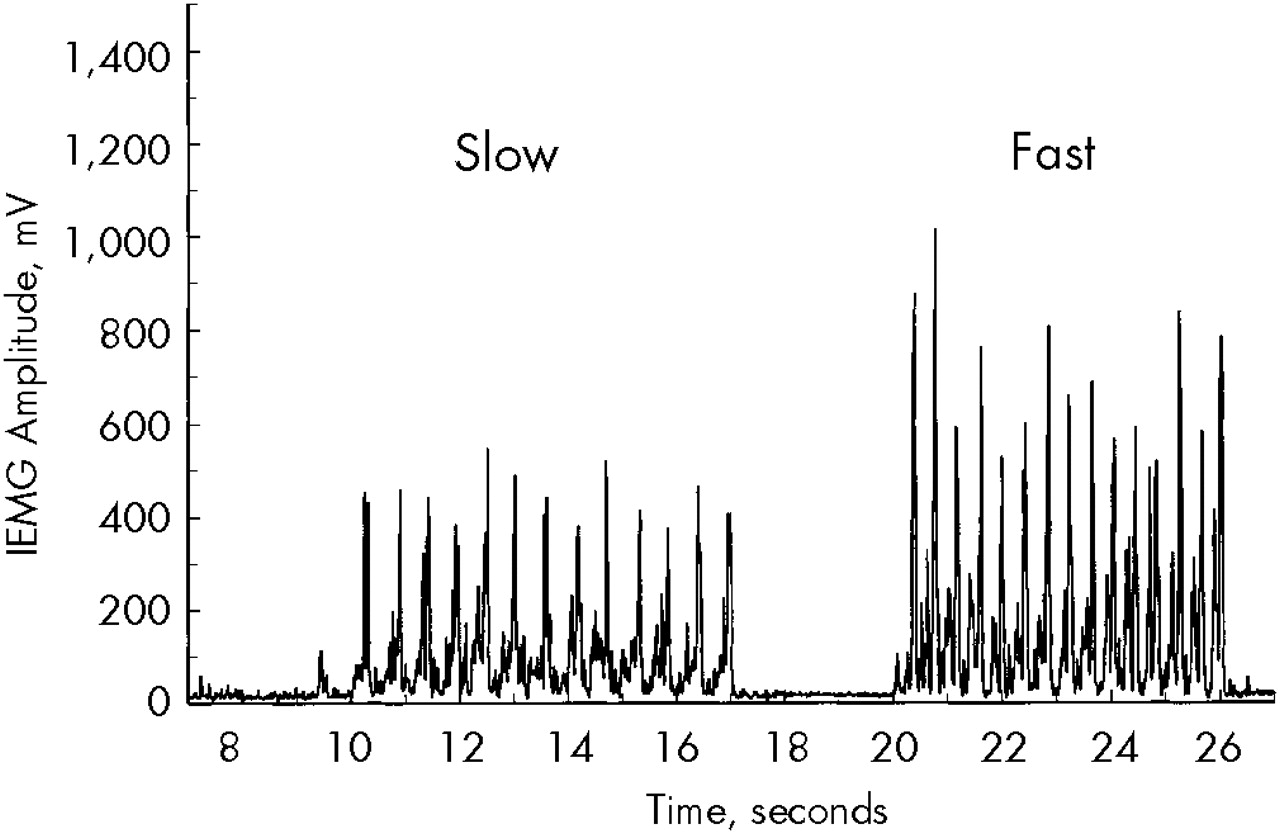

34 Thus, we quantified bradykinesia (speed of movement) by measuring the amplitudes of the EMG bursts associated with voluntary flexion of the wrist (

Figure 2). The rectified and smoothed EMG waveform was subjected to analysis consisting of identifying the peak amplitudes of the agonist bursts and averaging the highest 10 values. EMG values were unanalyzable for 5 patients because of technical problems associated with electrode contact.

For both EMG measures, the average scores from the left and right hands were used for estimating prevalence of EPS and for all statistical analyses.

Clinical Assessment of EPS

The motor subscale of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale

35 (UPDRS) was used to assess the presence and severity of extrapyramidal signs, including rigidity, bradykinesia, tremor, masked facies, and gait disturbance. Severity was rated on a 5-point equal-interval scale with “0” representing no impairment and “4” representing severe impairment.

Assessment of Neurobehavioral Disturbances

The Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale (Behave-AD

14) was used to assess the presence and overall severity of neurobehavioral disturbances, including psychosis, mood disturbances, wandering, and aggression. This 25-item scale was administered by interviewing the primary caregiver, who responded to questions concerning the patient's behavior over the preceding month. For the purpose of this study, subscores for delusions and hallucinations were used for dichotomizing patients into subgroups based on the presence or absence of these two symptoms. A subscale total score greater than “1” on the delusion or hallucination items was sufficient to consider the respective symptom present.

RESULTS

Prevalence of EPS and Psychosis

The mean Behave-AD total score was 7.19±6.8, with a range of 0–29. Seventeen patients (32.7%) were reported to have delusions and 7 (13.5%) hallucinations based on caregiver interview using the Behave-AD. There were overlapping symptoms in 5 patients who exhibited both hallucinations and delusions. Overall, 36.5% of the patients were reported to have at least one psychotic symptom.

The mean UPDRS total score for the motor items was 6.1±6.6, with a range of 0–24. Thirty-three patients (63.5%) scored at least a “2” on one item of this scale; the remaining 19 patients (36.5%) had total UPDRS motor scores of less than 2. Twenty patients (38.5%) were rated with at least mild rigidity, and 23 patients (44.2%) were rated with at least mild bradykinesia based on the UPDRS.

For the purpose of estimating prevalence of instrumentally derived EPS, cut-points were applied to the EMG scores for rigidity and bradykinesia based on normative data. The normative data were derived from a sample of 24 healthy gender- and age-comparable subjects. The mean age of the normal subjects was 73.3±10.4 years, and 14 (56%) were male. Cut-points were based on scores above (rigidity) or below (bradykinesia) the 95% confidence interval for the normal subjects. For the EMG measure of rigidity, the cut-point was 1.79 (derived from a mean of 1.46 and a standard deviation of 0.76). For the EMG measure of bradykinesia, the cut-point was 590 (derived from a mean of 726 and a standard deviation of 272). On the basis of these cut-points, 10 of the 52 patients (19.2%) exhibited rigidity based on abnormally high active/rest EMG ratios and 17 of 47 patients (36.2%) exhibited bradykinesia based on abnormally low peak EMG amplitudes.

Relationships Between Psychosis and EPS

Patients were grouped into two subgroups based on the presence or absence of psychotic symptoms.

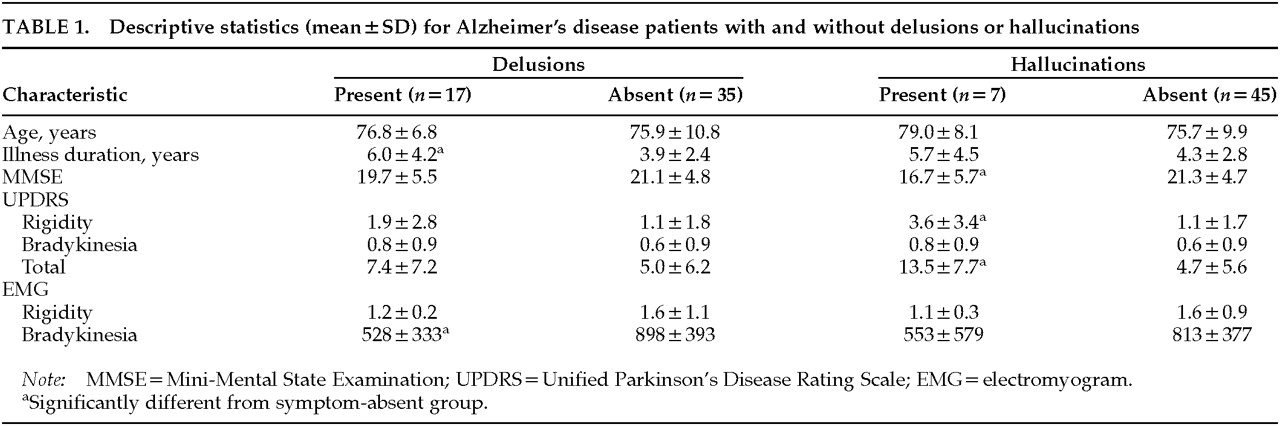

Table 1 shows the results of analyses comparing patients with versus patients without delusions or hallucinations on the clinical and EMG motor measures. Independent

t-tests indicated that AD patients with delusions had longer illness durations (

t=2.09;

P<0.05) and lower amplitudes on the EMG bradykinesia measure (

t=3.15;

P<0.01) than patients without delusions. AD patients with hallucinations had lower scores on the MMSE (

t=2.31;

P<0.05), and higher total scores on the UPDRS (

t=3.37;

P<0.01), with particular increase on the rigidity subscore (

t=3.09;

P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

In the present series of AD patients, by caregiver report, more than one-third exhibited neurobehavioral disturbances. Delusions were more predominant than hallucinations. The proportion of patients with delusions is somewhat higher than the 16% reported by Burns et al.

4 but is consistent with the 34% reported by Gormley and Rizwan.

1 The higher prevalence figures reported by this and previous studies for delusions in AD may be attributed to the use of direct face-to-face interviews with caregivers

15 rather than chart reviews. The relatively infrequent occurrence of hallucinations in our sample is also consistent with the literature.

1,6 Overall, the prevalence and distribution of neurobehavioral disturbances in the present sample of AD patients is representative of the AD population.

Both the UPDRS motor ratings and the EMG measures indicated that bradykinesia was the most prevalent parkinsonian feature. Overall, there was agreement between these two independent measures of bradykinesia (r=–0.41; P<0.01). Patients rated as bradykinetic on the UPDRS generally had lower EMG amplitudes than non-bradykinetic patients. However, there was disagreement between the observer ratings and EMG measures of rigidity. Nineteen patients were rated as having at least mild rigidity, whereas only 10 met criteria for rigidity based on the EMG measure. One explanation for this discrepancy may be related to the comprehensive nature of the UPDRS in rating parkinsonian rigidity. Five of the 11 motor items (exclusive of involuntary movements) pertain to the assessment of rigidity from three body areas, whereas the EMG procedure records muscle tone from the forearms only. An alternative explanation is that the EMG procedure may be overly sensitive to motor abnormalities associated with normal aging, whereas UPDRS ratings may be less sensitive to age-related increases in rigidity. The criterion for the presence of rigidity on the EMG measure was active/resting integrated EMG amplitudes greater than 1.5 standard deviations above the normal mean. Differentiating age-related from disease-related increases in muscle tone on the basis of a statistical cut-point may be more problematic if the within-sample variation in normal muscle tone is too large.

The focus of the present study was on the relationships between signs of parkinsonism and features of psychosis in AD patients. Yet features of AD, in addition to parkinsonian signs, were associated with psychosis. In particular, lower cognitive status based on MMSE scores was associated with the presence of hallucinations, and longer illness durations were associated with the presence of delusions. These results are consistent with previous research showing that psychosis is associated with more severe cognitive impairment

8,36 and that although delusions are present at all stages of the illness, they are more active during the moderate stages.

15We found that patients with delusions had significantly lower amplitudes on the EMG measure of bradykinesia than patients without delusions. These findings support the notion that motor and psychiatric disturbances may stem from a common pathophysiologic mechanism. Several investigators have postulated a dysregulation of dopamine

37 or an imbalance between dopamine and acetylcholine

38,39 in the pathophysiology of psychiatric complications in AD. Similarly, it has been hypothesized that parkinsonian bradykinesia stems from an increase in tonic inhibition brought on by excessive pallidal output to the thalamus, resulting in reduced responsiveness of motor cortices.

25,26The relationship between bradykinesia and delusions in our sample of AD patients raises the possibility that a common mechanism may be responsible for these characteristics in AD. There is strong evidence from neuroanatomical studies that links limbic with sensorimotor regions of the basal ganglia through midbrain dopamine neurons.

37,40,41 This evidence suggests that output from the ventral limbic striatum terminates on nigrostriatal dopamine neurons that innervate the sensorimotor striatum. Under normal conditions, the limbic striatum gates the flow of information through the sensorimotor striatum. Inhibitory projections from ventral limbic areas of the striatum to the substantia nigra pars compacta modulate the dopaminergic outflow to the striatum. However, when the dopaminergic system is disrupted, limbic outflow becomes disinhibited and alters the normal regulation of motor function within the sensorimotor striatum and leads to bradykinesia and perhaps rigidity.

25,26There are limitations to the present study. First, although the proportion of our sample of patients that exhibited delusions was consistent with the literature,

1,6 very few patients in our sample were reported to exhibit hallucinations. This limits the generalizability of our findings to the AD population at large, for whom hallucinations may be a significant component of their psychoses. Second, we were unable to detect an association between dementia severity on measures of cognitive function and either EPS or neurobehavioral disturbances, although such an association would be predicted from the literature.

19 This negative finding may be due to a relatively small sample size having insufficient power to detect such a relationship.

The results of the present study demonstrated a cross-sectional relationship between EPS and psychosis in AD. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine whether parkinsonism appearing early in the course of AD predicts the development of behavioral disturbances later in the disease. It is also possible that with instrumental techniques, one could uncover a subgroup of AD patients who are predisposed to develop clinically overt parkinsonism. The early detection of parkinsonism in AD may have a direct bearing on the pharmacologic management of cognitive disturbances. For example, there is suggestive evidence from patients enrolled in trials of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors who have since come to autopsy: those categorized as “responders” in terms of cognitive status were more likely to have pathological features associated with parkinsonism than not to have such pathology.

42 Given these findings, it may be advantageous to start treatment with a particular acetylcholinesterase inhibitor when the first signs of instrumentally derived EPS emerge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by National Institute on Aging Grants R01-AG14291 and AG05131. The authors acknowledge the University of California, San Diego, Alzheimer's Disease Research Center and, in particular, Kim Golden for her assistance in the collection and management of the data for this study.