Emergent Neuroleptic Hypersensitivity as a Herald of Presenile Dementia

Abstract

CASE REPORTS

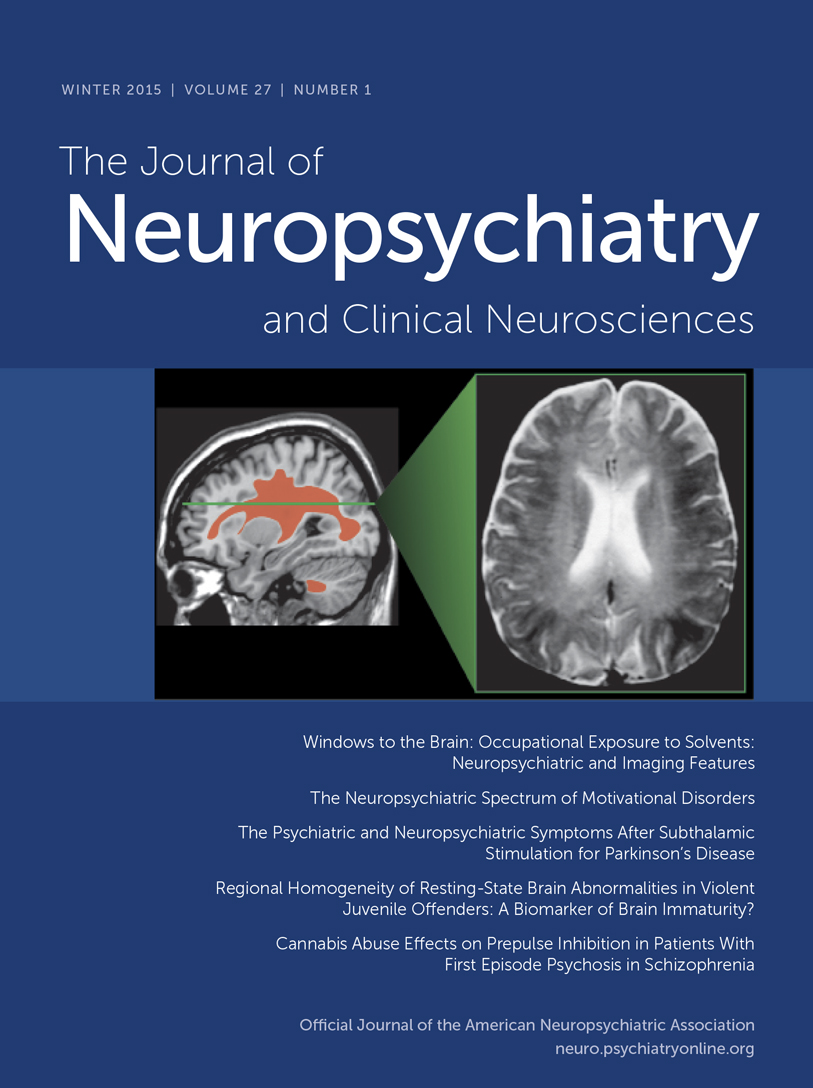

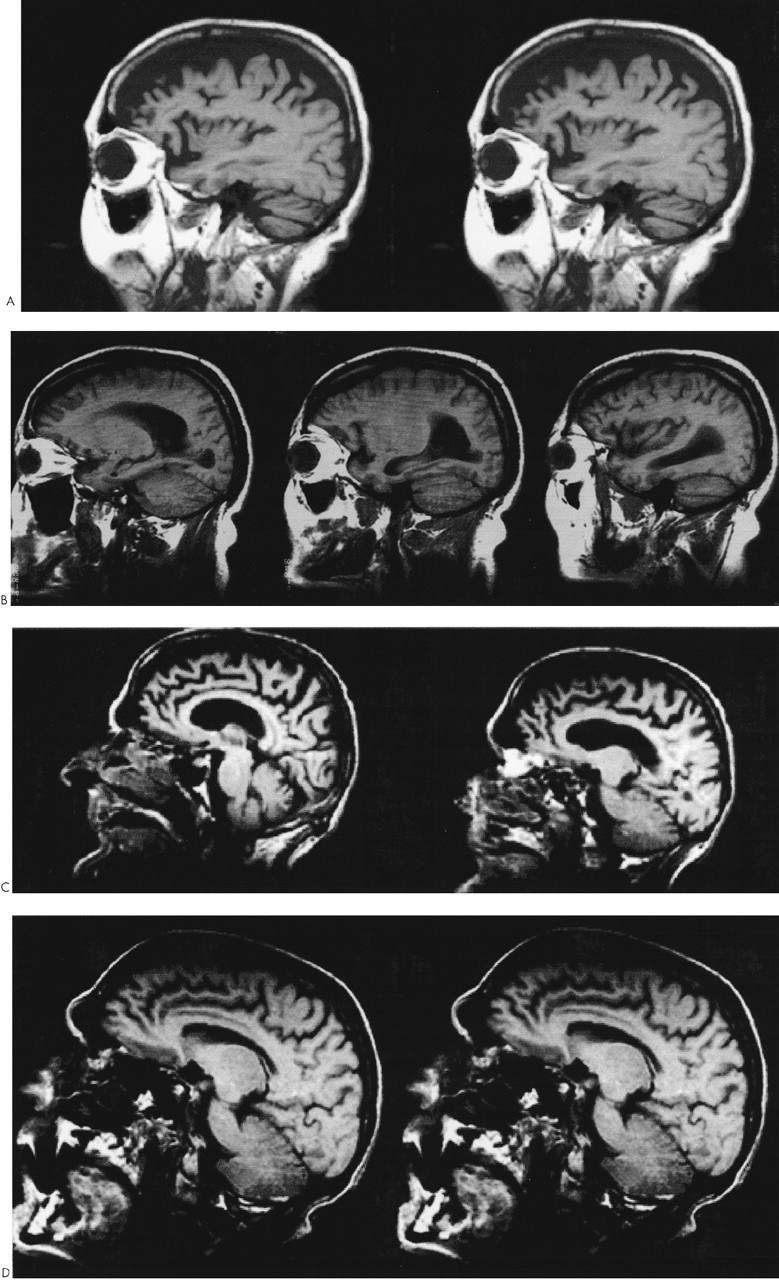

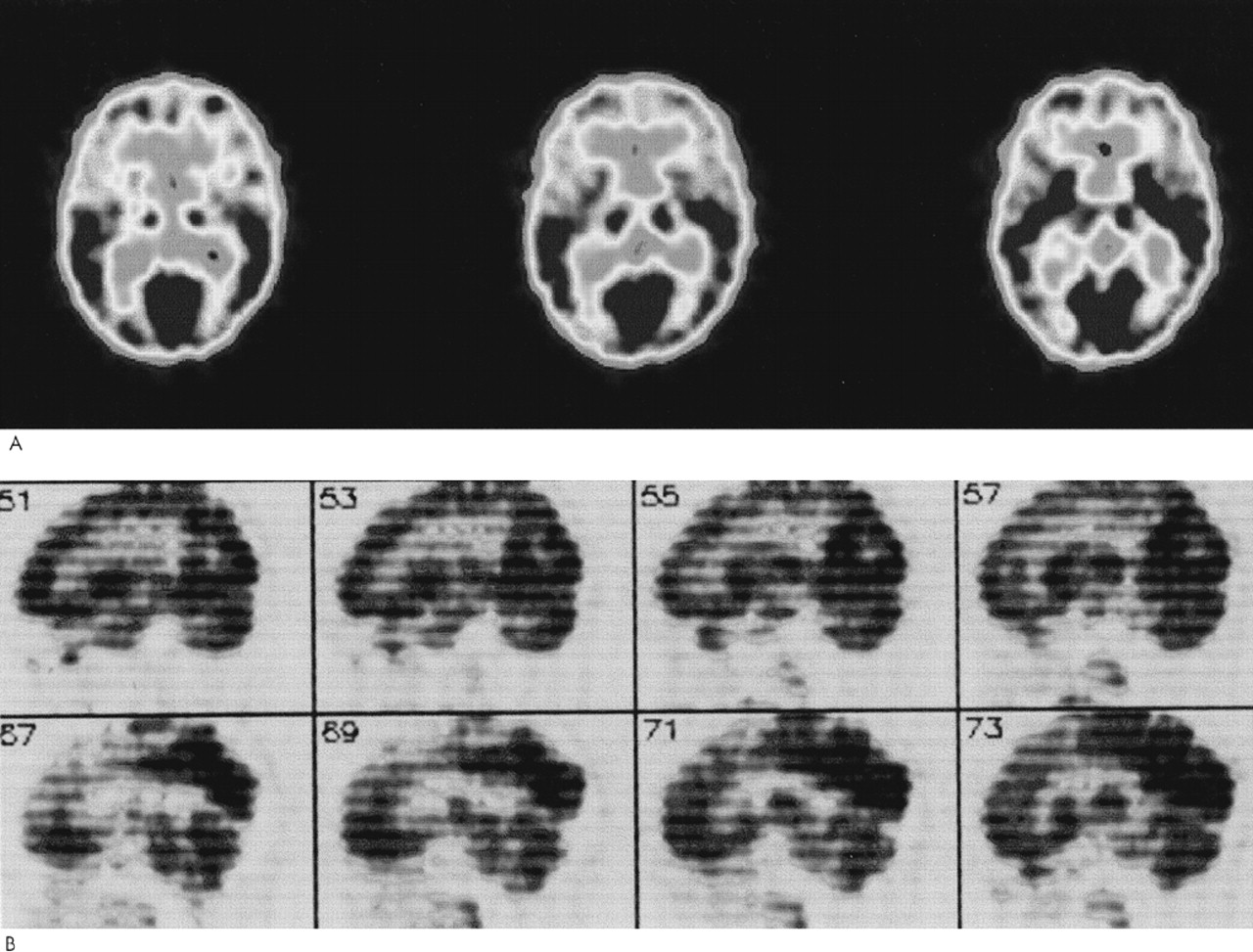

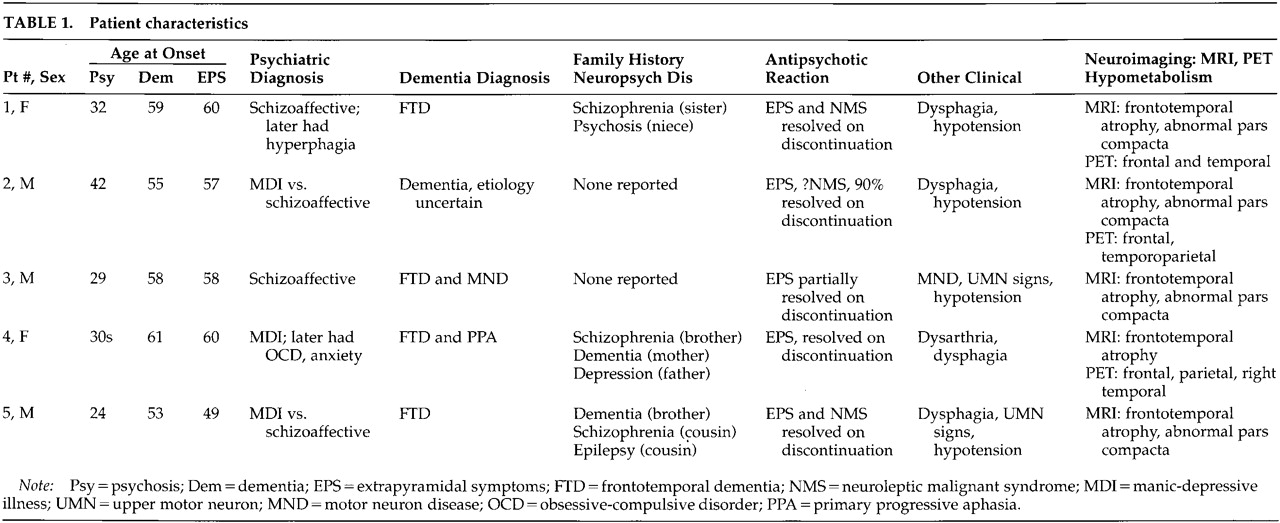

Patient 1. A 62-year-old woman with a prior diagnosis of FTD was hospitalized secondary to severe motor rigidity, delirium, dehydration, and aspiration pneumonia. The patient had a long psychiatric history of schizoaffective psychosis, with disorganized thinking and frequent spells characterized as manic. She had received antipsychotic medications for decades, chiefly haloperidol and trifluoperazine. A week prior to admission, she had had an increase in the dosage of her long-standing trifluoperazine to 20 mg and had started to develop confusion and greater extrapyramidal rigidity.About one and a half years previously, she first manifested extrapyramidal rigidity and personality and behavioral changes. There had been no change in her antipsychotic or other medications at the time of emergence of extrapyramidal symptoms. In addition, the patient had been on high doses of antipsychotics in the past, including 6 months on trifluoperazine 10 mg bid, without extrapyramidal signs. An evaluation at that time disclosed progressive aspontaneity and decreased goal-directed behaviors consistent with FTD. Her past medical history was otherwise negative. Her family history revealed a sister and a niece with psychotic disorders.On examination, the patient appeared acutely ill, with hypotension (blood pressure 85/53) and a temperature of 102.4 degrees. She had limited spontaneous speech and facial expression. She did not respond to commands, although voluntary movement was observed in all four limbs. Her neurological examination disclosed diffusely increased extrapyramidal tone with tremulousness of the upper extremities. Laboratory assessment revealed sodium 178, blood urea nitrogen 113, creatinine 4.3, leukocytes 17,600 (86% polymorphonuclear leukocytes), and initial creatine phosphokinase (CPK) of 1,644 IU. In addition to her pneumonia, the patient was considered to have NMS.The patient gradually recovered during her hospitalization. Her extrapyramidal rigidity entirely resolved after discontinuation of the trifluoperazine. She did not receive antiparkinsonian medications. Despite resolution of her movement disorder, she continued to manifest decreased verbal and spontaneous behavior and a dysexecutive syndrome. During the course of her illness, she manifested hyperoral behavior and a tendency to explore with her hands, behaviors consistent with the Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Although her neuroimaging changes were not entirely typical, both MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging suggested FTD (Figure 1A and Figure 2A). Moreover, she had changes in the pars compacta on MRI observed in some patients with Parkinson's disease (Figure 3B). The presence of motor neuron disease (MND) was considered, but was not seen on an electromyogram (EMG).

Patient 2. A 58-year-old man was hospitalized because of dementia and inability to care for himself. He had a long-standing history of either manic-depressive illness or schizoaffective psychosis and had recently developed neuroleptic hypersensitivity and a frontally predominant dementia. His psychiatric illness included multiple manic episodes and periods of depression with psychotic symptomatology treated with lithium, divalproex, and a range of antipsychotic medications. The patient had been on antipsychotic drugs for the majority of the prior 15 years, including chlorpromazine, thioridazine, haloperidol, and clozapine. The patient's past medical history also included poorly controlled diabetes, periods of heavy ethanol abuse, and prostate cancer of limited involvement treated conservatively. The family history did not disclose any specific or familial illnesses.One year prior to hospitalization, while on haloperidol, he became very rigid and “parkinsonian,” mute, and unresponsive. There had been no change in his neuroleptic treatment, ongoing haloperidol dosage, or other medications. The assessment at that time showed a markedly elevated tone, slight temperature elevations, and orthostatic hypotension, but his CPK did not rise above 200 IU. These symptoms resolved after discontinuation of the haloperidol. After that episode, however, it became clear that the patient had a behavioral change with disinhibition and a progressive cognitive decline. His executive skills and memory were impaired, and his ability to perform activities of daily living had declined.On the current hospitalization one year off of neuroleptics, he was alert and oriented to time and place but tended to sit and stare with little spontaneous verbal output. Mental status testing disclosed deficits in verbal memory and learning, decreased verbal fluency, poor visuospatial skills, and deficits on frontal-executive tasks. The neurological examination was unremarkable except for mild increased tone bilaterally and a decreased gait.The patient underwent a dementia evaluation. He was initially suspected of having normal pressure hydrocephalus because of large ventricles and a suspicious cysternogram; however, ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement did not alter his clinical symptoms or progression. He was then suspected of having a form of FTD with MND because of disinhibited behavior, personality change, and swallowing difficulty; however, an EMG did not disclose MND. Review of his MRI suggested predominant frontal atrophy and possible changes in the substantia nigra region (Figure 1B and Figure 3C). A PET scan disclosed hypometabolism in the frontal and temporal regions with some involvement of parietal regions; however, the scan was suboptimal because of movement (see Figure 2). Subsequently, the patient continued to show hypersensitivity to reintroduction of antipsychotic drugs and was maintained on valproate alone.

Patient 3. A 61-year-old man with a long history of schizoaffective disorder was hospitalized because he had developed dysphagia, fasciculations, and an aspiration pneumonia. For at least 6 months the patient had experienced progressive swallowing difficulty, culminating in respiratory difficulty and a productive cough. Three years previously, the patient had received the diagnosis of dementia with progressive disengagement and apathy.The patient had a 30-year history of a chronic affective psychosis and had been on a range of antipsychotic drugs for the majority of that time. He had received chlorpromazine, trifluoperazine, and risperidone as well as lithium. Three years previously he had developed severe parkinsonism while on at least a 3-month unchanged dosage of trifluoperazine and lithium. There had not been any changes in any other medications or dosages. His parkinsonism included cogwheel rigidity, hypomimia, and decreased verbal output. He was initially thought to have Parkinson's disease, but a brief trial of levodopa/carbidopa failed to improve his extrapyramidal symptoms. Most of these symptoms, however, resolved on discontinuation of the antipsychotic medication. Further evaluation disclosed a progressive language impairment with onset coincident with his extrapyramidal reaction. He had a decline in verbal output as well as a decrease in reading and writing ability, and mental status testing revealed declines in verbal memory and in executive functions.Examination on this hospitalization revealed progression of his dementia, with limited verbal output and decreased spontaneous interaction. On neurological examination, he had difficulty protruding his tongue, fine and gross fasciculation in the upper extremities, slight increased tone, and brisk reflexes. His EMG confirmed the presence of MND. Review of his MRI suggested frontotemporal atrophy and smudging of the pars compacta towards the red nucleus on T2-weighted images (Figure 1C and Figure 3D).This patient had a protracted course with partial recovery. He received the diagnosis of FTD with MND and was started on riluzole 50 mg q12h. His parkinsonism was mild when he was off of any antipsychotic medication. The patient was eventually transferred to a chronic care facility.

Patient 4. A 65-year-old woman with a 3- to 4-year history of dementia and a nearly 30-year history of manic-depressive illness presented for further diagnostic assessment of her dementia. Past medical history included manic episodes and periods of profound depression previously managed with lithium. Family history disclosed that her mother had died with an unspecified dementing illness and her brother had schizophrenia.Five years previously, the patient had developed an extrapyramidal reaction to haloperidol. At that time, she had been on various antipsychotic medications as well as lithium or divalproex for most of the prior 20 to 30 years, particularly thiothixene (up to 30 mg/day) and haloperidol. The specific medication and dosage had not been changed at the time she developed neuroleptic hypersensitivity. She developed severe rigidity and muteness, but no clear fever, elevation of CPK levels, or other evidence of NMS. Discontinuation of the haloperidol resulted in resolution of her extrapyramidal rigidity without necessitating a trial of antiparkinsonian medications. Nearly coincident with this reaction, her family noted a decline in her speech and language and changes in her personality. She became unable to complete goal-oriented behaviors and developed new compulsive behaviors, including hoarding rolls of toilet paper.She was reevaluated 5 years after her neuroleptic reaction and after the onset of her dementia. The patients had limited spontaneous interaction. Her speech was strained and dysarthric, and there were paraphasic errors on verbal output and paralexic errors on writing. On further testing of her writing she had prominent errors in grammatical and sentence structure. Memory and simple calculations appeared intact. The patient could do simple constructions but had difficulty with the planning and organization of complex figures. She had perseverations on Luria motor sequencing tasks and was very concrete in interpreting proverbs. The neurological examination was abnormal because of dysarthria, mild leadpipe rigidity bilaterally, and palmomental reflexes.The clinical diagnosis was probable FTD with primary progressive aphasia. She had a frontally predominant dementia syndrome with a decline in verbal output, speech, and language. Neuropsychological testing confirmed the presence of marked impairment in verbal fluency and cognitive flexibility along with milder impairments in verbal memory and visuospatial skills. Her MRI scan performed elsewhere suggested greater frontotemporal atrophy; the imaging was not assessed for midbrain changes. PET imaging showed hypometabolism in the bilateral frontoparietal and right superior temporal regions (Figure 2B). Her symptoms were eventually managed with sertraline 100 mg bid and low-dose olanzapine (2.5 mg qd).

Patient 5. A 54-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder had a history of several episodes of severe extrapyramidal rigidity during the preceding 5 years. His physicians had not been able to distinguish between the development of Parkinson's disease and the possible contribution of his chronic antipsychotic drug therapy. Antipsychotic medications were taken for most of his adult life and included haloperidol (oral and decanoate), prolixin (oral and decanoate), chlorpromazine, thioridazine, thiothixene, clozapine, and risperidone. Prior to age 49, the patient had not experienced neuroleptic sensitivity even on high doses of these medications. Trials of levodopa/carbidopa and amantadine had not improved his extrapyramidal symptoms.The patient's medical history was also significant for a cognitive decline. During the prior one or more years he had developed progressive deficits in memory, verbal fluency, and executive functions. These cognitive changes were superimposed on his chronic psychosis with affective and paranoid features, delusions of grandeur, hyperreligiosity, euphoria, and disorganized speech. Family history was positive for dementia in a brother and schizophrenia in a cousin.The patient was hospitalized because of a severe rigidity, delirium, mutism, dehydration, and respiratory difficulties on olanzapine 10 mg qd. On examination, he was rigid and unresponsive. He was also febrile, dehydrated, hypotensive, dysphagic, and had an aspiration pneumonia. He had little spontaneous verbal output or behavior and was unable to communicate or follow instructions. He could make sounds that he clearly intended as meaningful, but they were indecipherable. Neurological examination disclosed masked faces, absent gag reflex, and extreme motor rigidity. On admission his CPK was elevated at 454. The patient was treated with tracheostomy, respiratory and intensive care support, rehydration, discontinuation of his antipsychotic medication, and a period of antibiotics and bromocriptine. He gradually resolved from his delirium, extreme rigidity, and other NMS symptoms but remained with dementia.The diagnosis was FTD with extreme sensitivity to antipsychotic agents, including NMS to olanzapine. MRI scans were remarkable for frontotemporal atrophy and suggestive abnormalities in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra (Figure 1D and Figure 3E). A subsequent EMG did not reveal evidence of MND.

DISCUSSION

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).