Postictal psychosis (PIP) is a common sequela of inpatient video-EEG monitoring studies, with a reported frequency of 6.4% in a recent study at an epilepsy center.

1 PIP is a particular safety concern in patients undergoing invasive monitoring, and repeated episodes of postictal psychosis may presage the development of chronic, enduring psychotic states in some patients.

1–4 Several neurologic factors are associated with an increased risk of developing PIP. These include bilateral seizure foci, etiologic processes associated with bilateral limbic lesions (e.g., encephalitis, head trauma) and a relative increase in seizure frequency, or “cluster,” preceding the appearance of psychotic symptoms.

1,3,4–7The literature provides limited data on baseline psychiatric symptoms in patients who subsequently experience PIP. In a previous small retrospective study, patients with PIP were proportionally more likely to report a history of psychiatric hospitalizations than patients without PIP.

5,7 Szabó et al.

7 reviewed six studies involving 43 patients and encountered only 2 cases with interictal affective disorder. Other studies comparing complex partial epilepsy (CPE) patients with and without PIP found no premorbid psychiatric differences.

1,4,7,8 Likewise, family history of psychiatric illness has not been associated with PIP.

1,3,6,7,9 There is little information regarding features of personality disturbance that might predict an increased risk for PIP. Among the personality features that may be of interest as possible predictors of vulnerability to PIP are schizotypal and paranoid personality traits, which are reportedly markers for vulnerability to schizophrenia in psychiatric populations.

10Most published studies do not suggest that family and individual psychiatric histories differ between CPE patients with and without PIP. However, methodological issues might explain the reported negative findings. Existing studies are mostly retrospective and have been limited to either case studies, samples without controls, or very small control groups. Lack of systematically applied criteria for documenting family and personal psychiatric history, as well as limited statistical power related to small sample sizes, may also have contributed to the largely negative findings in the literature to date. The use of categorical diagnoses developed mainly for non-neurologic patient populations, as opposed to continuous measures of psychiatric symptoms, could limit the sensitivity of studies comparing baseline psychiatric features of patients who do and do not subsequently develop PIP.

The present study prospectively examines a consecutive sample of 622 patients with CPE undergoing video-EEG (VEEG) monitoring. These patients were evaluated at baseline in a nonpsychotic state by structured psychiatric interviews, which included self- and clinician-rated scales in addition to systematic assessment of family and individual psychiatric histories. The subjects who subsequently developed PIP during their VEEG study are compared with the remainder of subjects who did not. The a priori hypothesis tested was that individual and family history psychiatric variables would predict vulnerability toward the development of PIP in patients with CPE. Specifically, we hypothesized that patients developing PIP will be more likely to have a history of prior psychiatric hospitalization, higher baseline ratings of schizotypal and paranoid personality features, and a family history of psychotic disorders than those who do not develop PIP.

RESULTS

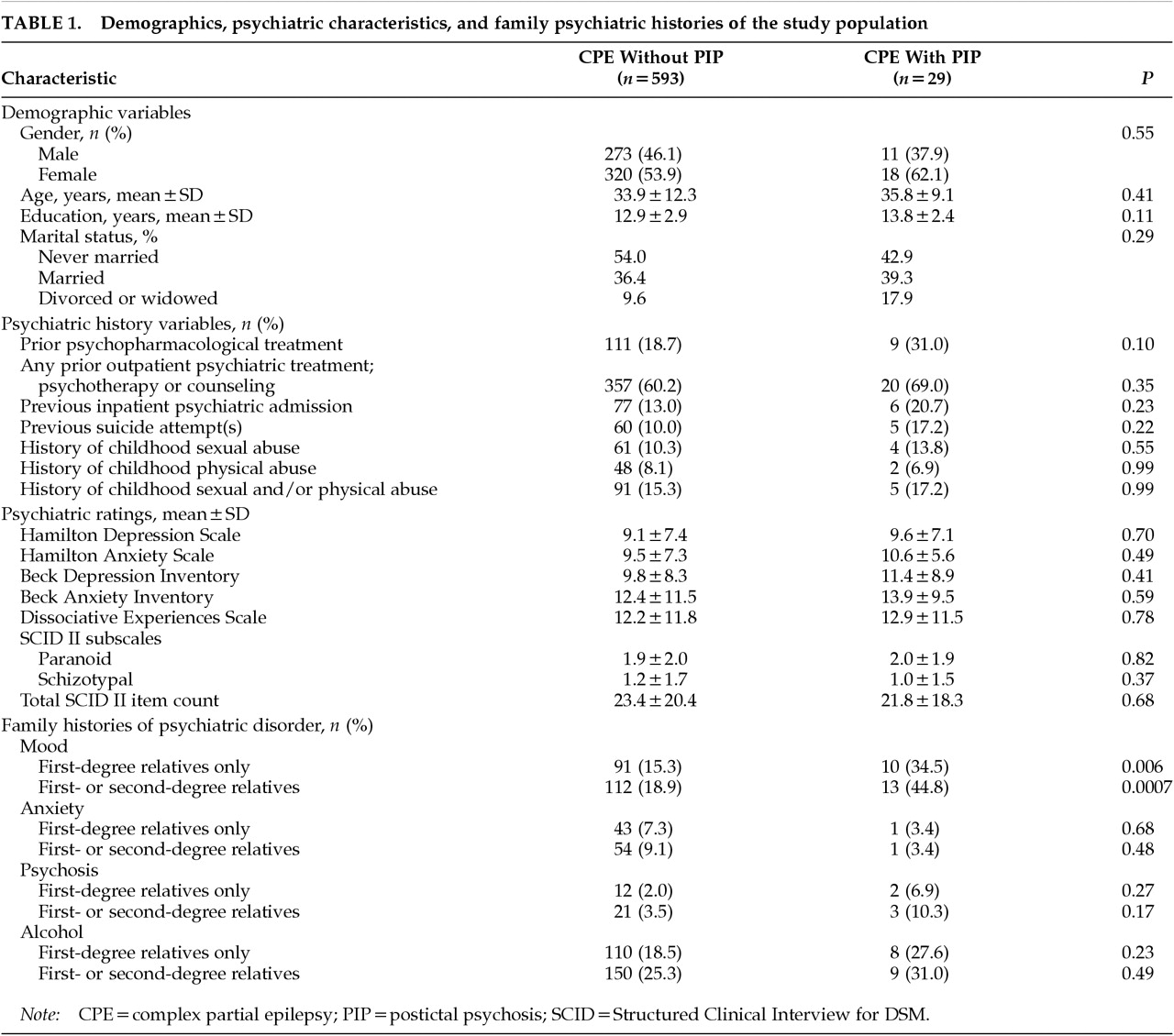

Table 1 summarizes the demographic features, individual and family psychiatric history variables, and psychiatric ratings of the PIP and comparison groups. The two groups do not differ significantly with respect to gender. Twenty-nine patients (4.7% of the entire series) went on to develop a postictal psychosis during VEEG monitoring. PIP subjects have a nonsignificantly higher prevalence of suicide attempts and of psychopharmacological, inpatient, or outpatient psychiatric treatment.

Scores on self- and clinician-rated depression and anxiety scores and schizotypal and paranoid personality traits do not differ significantly between groups. As with the psychiatric history variables, family histories of anxiety, psychotic, and alcohol use disorders are nonsignificantly higher in the PIP group, and only a family history of mood disorder appears to be significantly more prevalent among patients with PIP (P=0.0007 for first- and second-degree relatives combined).

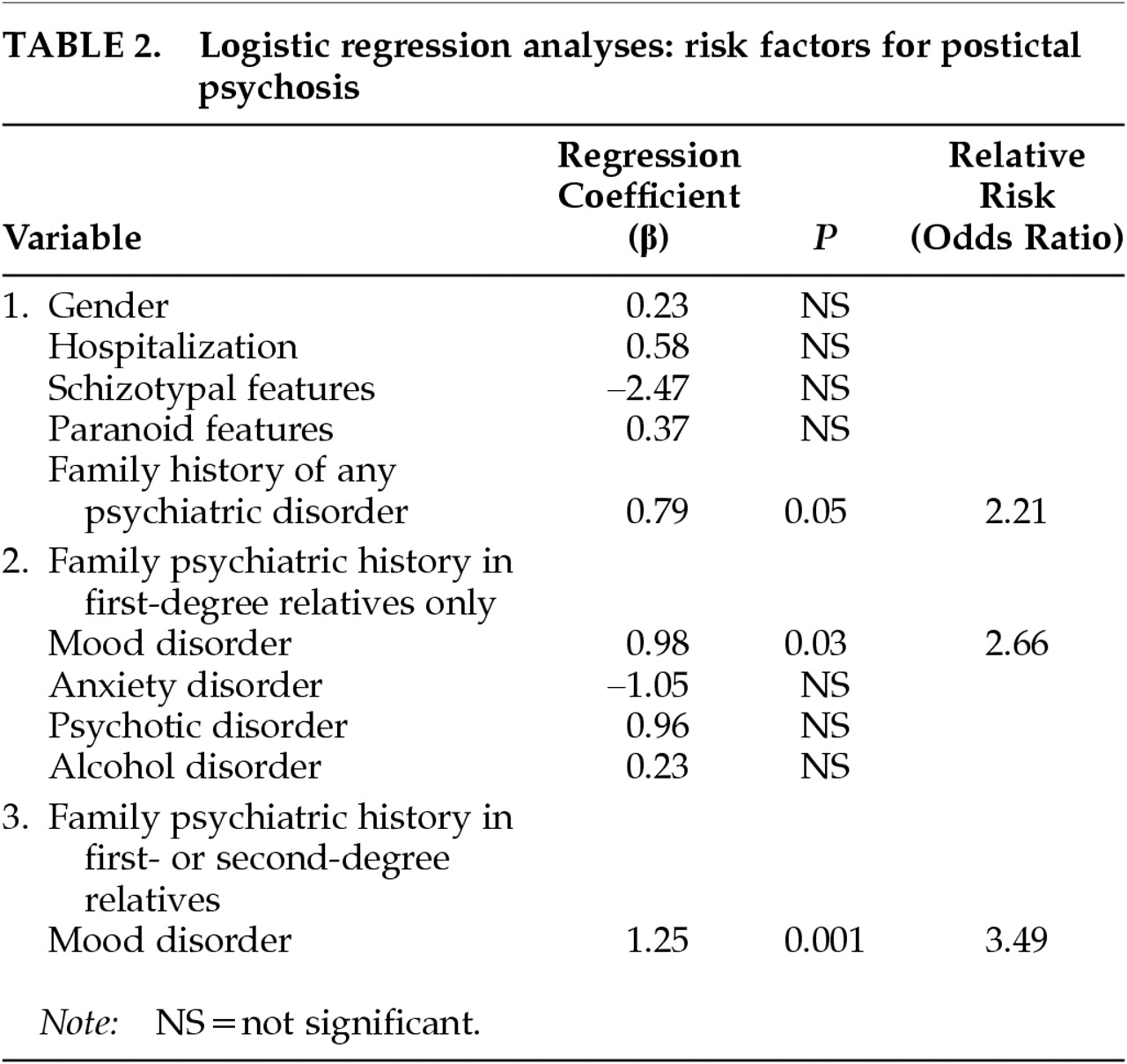

Table 2 presents the findings of the logistic regression analysis. Because female gender has been reported as a risk factor for chronic interictal psychosis,

4,22 we included gender in the first regression. Gender, prior inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, schizotypal and paranoid personality features, and the presence of any family psychiatric history (in any of the four diagnostic categories and in either first- or second-degree relatives) were entered together in the first equation. A positive family history of psychiatric disturbance was the only variable that contributed significantly to the prediction of PIP: patients with family members who had mood, anxiety, psychotic, or alcohol disorders were more likely to develop PIP (

P=0.05; odds ratio [OR]=2.21). To determine which of the family histories of the four types of disorders were implicated (among first-degree relatives only), we examined each as an independent predictor and found only mood disorder to emerge as significant. As

Table 2 shows, with a family history of mood disorder in a first-degree relative, a patient is 2.66 times more likely to develop PIP than if family history is negative (

P=0.03). The predictive effect was even stronger when family history of first-degree relatives with mood disorder was entered into the equation alone without the noise of the nonsignificant variables (β=1.07;

P=0.009; OR=2.90). Finally, we combined the family psychiatric histories of mood disorder to include either first- or second-degree relatives in the final regression. We found that the risk of developing PIP was 3.49 times higher (

P=0.001) among patients who had a positive family history of mood disorder in either first- or second-degree relatives.

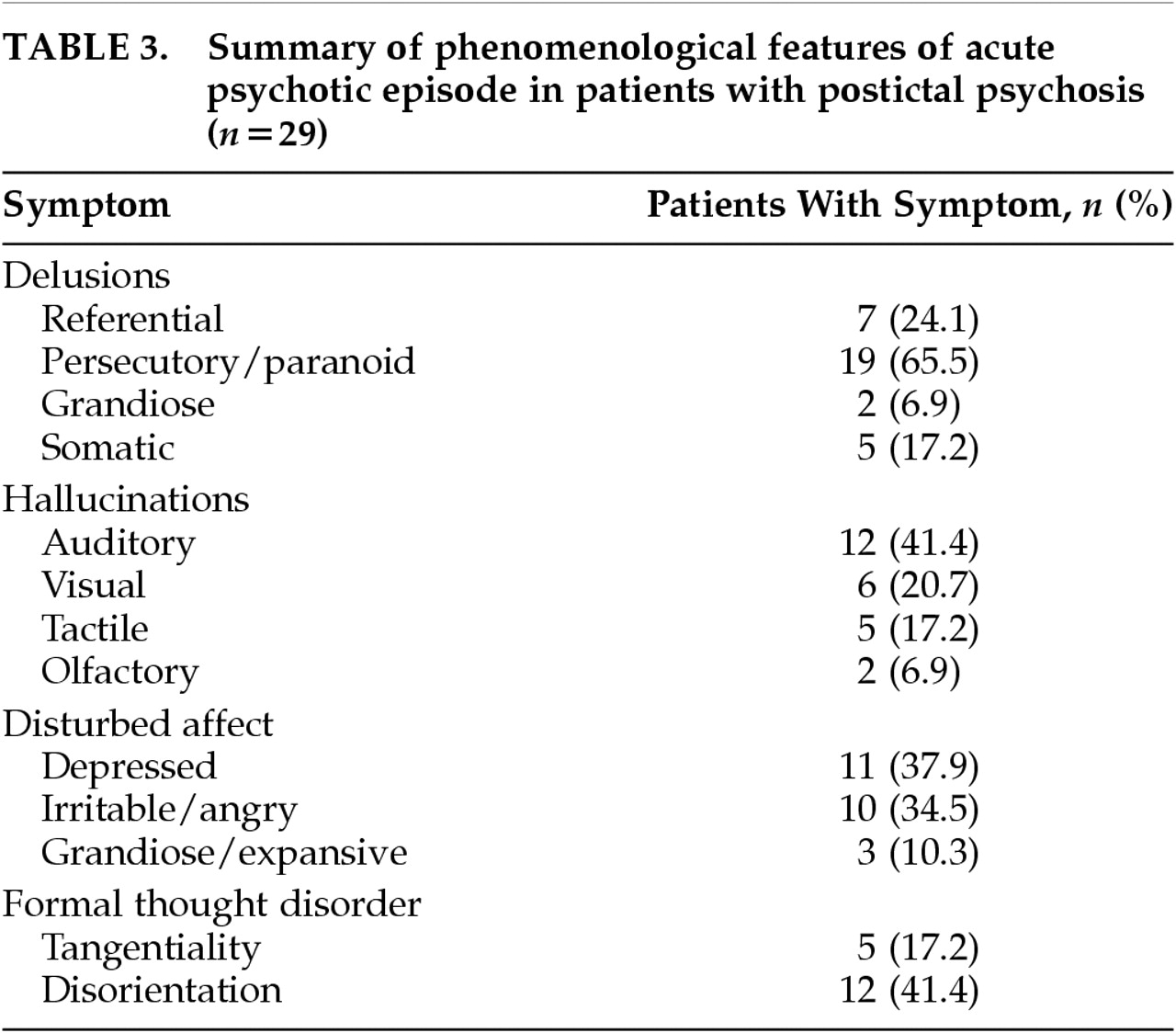

Table 3 summarizes the major psychiatric phenomenological features of the 29 patients with PIP. One striking feature is the relative prominence of paranoid symptomatology, which was present in 19 patients (65.5% of the PIP group). Referential delusions most often involved religious themes. Somatic delusions frequently involved aspects of the VEEG monitoring process: for example, that the electrodes were affecting the patient's heart or causing the patient's hair to fall out. Other notable aspects of PIP phenomenology in this series were the relative prominence of mood symptoms and the relatively unelaborated nature of auditory hallucinations. Many patients simply heard their name called or heard nonarticulated sounds without semantic content. True examples of Bleulerian formal thought disorder, i.e., loosening of associations (subsumed in DSM-IV under derailment or incoherence), were relatively infrequent, occurring in only 5 patients (17.2% of the PIP group). Some degree of gross disorientation to time or place persisting beyond the acute postictal period was seen in 12 patients (41.4% of the PIP group).

DISCUSSION

This study reveals that family history of mood disorder, but not psychotic illness, is associated with an increased risk of PIP. Baseline psychiatric ratings including self-and clinician ratings of mood, anxiety, and schizotypal or paranoid personality traits did not distinguish patients who subsequently developed PIP from those who did not, nor did psychiatric historical variables including prior psychiatric treatment and abuse histories.

The present study addresses some methodological limitations of previous work on this topic. Specifically, this study incorporated a prospective design, a large control group, systematically applied criteria to measure psychiatric symptomatology using standardized instruments, and multivariate statistical analysis. In addition, a single rater (K.A.) obtained all of the clinical data, eliminating interrater reliability as a potential source of variance. Although the rater could have been influenced by knowledge of the apparent history of a previous episode of PIP in 11 patients, the major finding that emerged (family history of mood disorder) was not the one hypothesized (family history of psychosis).

The proportion of patients developing PIP during their VEEG monitoring in this series was 4.7%. This figure underestimates the overall prevalence of PIP among surgical candidates because of the exclusion of patients with postictal or interictal psychotic symptoms already in evidence prior to the psychiatric evaluation. During the period of the recruitment, 8 patients developed acute PIP before psychiatric evaluation could be completed, and 6 patients were admitted with evidence of chronic interictal psychotic symptoms that were exacerbated during the monitoring study. If these 14 patients are grouped with the 29 patients with PIP that were included in the data analysis, then the total prevalence of PIP among the consecutive series of surgical candidates is 6.7%, very similar to the 6.4% incidence reported by Kanner and colleagues.

1The prevalence of family histories of psychiatric disorders reported in this study appears to have some consistency with the literature, which offers a degree of assurance regarding the family history methodology. There are, for example, at least three well-defined estimates of the prevalence of a positive family history of alcohol use disorders from large U.S. population samples. These estimates include 53% for alcohol use disorders among any first- or second-degree relatives, including children;

23 40% for first-, second-, and third-degree relatives;

24 and 24% for first-degree relatives including children.

25 The inclusion of children or third-degree relatives might explain why the estimates cited above exceed the estimates of the prevalence of a family history of alcohol use disorders among subjects in the present study. Our study excluded children and third-degree relatives in the family history. For first-degree relatives only, the present study found an overall prevalence of 19.0%, which is comparable with the estimate of Midanik et al.

25 that reported 24% for first-degree relatives. The family history methodology in the present study appears to have yielded relatively conservative estimates of the prevalence of a family history of psychiatric disorder, which might be at least partly explained by the exclusion of children and third-degree relatives. A conservative bias in making a diagnosis is reportedly associated with greater reliability in the psychiatric family history method using Research Diagnostic Criteria.

20 We emphasized reliability, not sensitivity, because the salient issue was not to define prevalence in this population, but rather the

relative prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses in the families of CPE patients with versus those without PIP.

The levels of baseline psychiatric symptomatology measured with the BDI and BAI were consistent with the results reported on surgical candidates with CPE. Strauss et al.

26 reported a mean BDI of 9.0 for 84 patients, and Hermann et al.

27 reported a mean BDI of 8.7 for 96 patients; we found a mean BDI of 9.8. The studies of Strauss et al.

26 and Hermann et al.

27 included only patients with unilateral foci but otherwise appeared to match the inclusion criteria in the present study. Hermann et al.

27 also reported on the BAI and found a mean score of 9.7 in their subjects, compared with 12.4 among the control subjects in this study. These mean scores on the BDI and BAI are consistent with mild but clinically significant depression and anxiety.

15,16 To provide further perspective, a BDI cutoff of 18 to 20 is commonly used to define major depression, and a mean BAI of 18.8 has been reported in generalized anxiety disorder and 27.3 in panic disorder.

15,16 Neither of the studies cited above

26,27 included clinician-rated instruments; however, the results obtained using the clinician-rated Hamilton depression and anxiety scales also yielded results that were consistent with mild but clinically significant depression and anxiety.

18,19The morbidity and mortality associated with PIP is clinically significant. Progression from acute PIP to chronic interictal psychosis has been reported by Kanner et al.

1 and by Logsdail and Toone.

3 Acute PIP and chronic interictal psychoses are both associated with the tendency toward clustering of seizures, which also suggests that acute PIP may progress to chronic psychosis in the presence of a common underlying neurologic risk factor.

4 Of the 14 patients described by Logsdail and Toone,

3 4 were dead at follow-up over an 8-year period. In the present study, 3 of the 29 patients in the PIP group are now deceased over a period of observation of 6 years, as are 2 of 6 patients who were omitted from the analysis because of chronic interictal symptoms.

The association of a family history of mood disorder to PIP was not expected. One possible explanation is that a family history of mood disorder is associated with an abnormality of the modulation of excitatory neurotransmission, resulting in a greater tendency toward epileptic seizure clustering or multiple seizure foci that could facilitate or permit the development of psychosis. Evidence of reduced activity of the inhibitory neuromodulator serotonin (5-HT), has been reported in depression

28,29 and includes apparently consistent effect of enhancement of 5-HT function by diverse antidepressants.

28 Levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and GABA-synthesizing enzyme are reportedly lower in depression, and low plasma GABA may be a trait marker in some depressed patients independent of mood state.

28,29 EEG studies in mood disorders provide evidence of altered modulation of CNS excitatory neurotransmission: the incidence of epileptiform activity on EEG is reportedly higher in mood disorders than in other psychiatric disorders or in nonpatient controls,

30 and paroxysmal epileptiform activity has been associated with suicidal behavior.

31 Clinical evidence possibly associating vulnerability toward psychosis with altered excitatory neurotransmission in mood disorders includes observations that patients with psychotic depression who receive electroconvulsive therapy seize at lower thresholds, and with longer duration, than patients with nonpsychotic depression,

32 and that epileptiform activity is more frequently associated with psychotic forms of mood disorder than with schizophrenia.

33Some additional clinical observations are consistent with a link of mood disturbance to vulnerability toward psychosis in the presence of a neurobiological provocation. Alcoholics

34 and cocaine users

35 who have histories of substance-induced hallucinations have higher levels of depression than do alcohol or cocaine users without histories of hallucinations. The relative prominence of mood symptoms in the clinical phenomenology of acute PIP, observed in this study and in others,

3,36 is also compatible with the concept of a shared relationship of mood disturbance and vulnerability toward development of psychosis in the presence of epilepsy. Various alterations of neural plasticity, such as sensitization or kindling, sharing the common general attribute of progressive enhancement of neural responses to stressors, have been suggested to play a role in mood disorders and psychosis in epilepsy.

4,37–39 Mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and CPE all frequently follow a natural history of augmentation over time, with progressively smaller provocations evoking progressively stronger exacerbations. This natural history and the efficacy of anticonvulsants in some mood disorders have been viewed as suggesting that a heritable alteration of neural plasticity may operate in mood disorders,

38,39 which could permit or facilitate the development of psychotic symptoms in the presence of a neurobiological stressor such as epilepsy.

4,37,40In view of the apparent potential for devastating impact on the lives of patients, further study of PIP is compelling from a clinical standpoint. From a theoretical standpoint, PIP also offers an interesting model of acquired psychosis. Investigation directed at understanding the etiologic basis of PIP is warranted in view of its clinical significance, and could prove rewarding as an approach to studying the neurobiology of psychosis.