Initially, treatment of Parkinson's disease (PD) with levodopa ameliorates the symptoms of bradykinesia, tremor, rigidity, and postural instability.

1 However, complications often accompany progression of disease and continued treatment. One such complication is increasingly shorter duration of motor benefit from each dose of levodopa, leading to frequent “off” periods with increased parkinsonian symptoms during the course of the day.

Although fluctuations in response to levodopa are typically defined by changes in motor signs, autonomic and psychological fluctuations may occur.

2,3 Some degree of sadness during times of motor dysfunction is not surprising, and many patients with motor fluctuations report worse mood when “off” than when “on.”

4–10 However, a minority of patients develop clinically significant off-period depression.

2–6,11,12 Akathisia or anxiety may accompany these brief periods of depression,

3,7,8,13,14 and some patients also have on-period manic symptoms.

2,4,5,12,15 These more severe mood fluctuations may produce more disability than motor fluctuations for some patients.

16Although mood fluctuations in PD have been reported for decades, our understanding of them remains limited.

17 Many authors describe mild changes that remain within the normal range.

6,9,18,19 Most reports of clinically significant mood changes do not allow an estimate of prevalence.

2–4,11,12 Although mood fluctuation can be distinguished phenomenologically from the typical persistent sadness of major depression or the steady high of mania,

20 it is not clear whether levodopa-related mood fluctuation occurs more frequently in patients who have had major depression. In addition, there is little information about neuropsychiatric or motor comorbidity associated with mood fluctuations; the existing literature consists almost exclusively of small studies.

13,21As a first step toward addressing some of these questions, we reviewed our experience at the Washington University School of Medicine Movement Disorders Center. We looked for evidence from existing clinical records that would address the relationship of clinically apparent mood fluctuations to other psychiatric illness and to parkinsonian motor features.

METHODS

Procedures

The Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee approved these studies. Movement disorders specialists at the Washington University Movement Disorders Center examined all patients and recorded all clinical information, including medical history and general and neurological examinations, in an electronic records system. Between 1996 and 2000, we evaluated 1,063 new parkinsonian patients, including both unselected (self-referred) and physician-referred patients.

In 1996, the authors began recording diagnoses of “PD with motor fluctuations” or “PD with mood fluctuations” in patients' medical records. For this report, we carefully reviewed the complete medical records of all patients with either of these diagnoses, together with all medical records in which the following words occurred in the history, assessment, or recommendation sections: “mood fluctuations,” depression, anxiety, or hypomania. From this sample we identified patients with clinically significant mood fluctuations. Because the data were obtained for clinical purposes and reviewed retrospectively, the phenomenology of anxiety, depression, or mania is not always recorded in detail. Thus for many patients it is not known whether the patient experienced 5 of 9 criterion A symptoms of the DSM-IV major depressive syndrome during “off” periods,

22 or the corresponding syndromal criteria for anxiety or mania. For the purpose of this study, we diagnosed “clinically significant mood fluctuations” only in patients with depressive, anxious, or manic symptoms that were a focus of clinical concern and were consistently associated with expected peaks or nadirs of levodopa dosing. In each case, 1) the treating physician believed the mood complaints were clinically meaningful, and 2) the reviewing physician agreed that the patient's symptoms corresponded to DSM-IV diagnoses of “anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition” or “mood disorder due to a general medical condition” (with depressive or manic features).

23 Mood fluctuations were classified by the reviewing physician as “on-” or “off-period” depending on the association with levodopa dose schedule and the motor symptoms experienced by the patient at the time of the mood symptoms.

We defined disease severity with the modified Hoehn and Yahr scale

24 at the most recent rating; dementia (of any etiology) according to DSM-IV;

23 and psychosis as one or more episodes of visual or auditory hallucinations. The age at onset of parkinsonism was defined as the age at which patients developed their first symptoms. Clinical depression refers to steady (not fluctuating with levodopa) sadness or anhedonia that was severe enough to require antidepressant treatment.

Two control groups were compared with the mood fluctuators. The first control group consisted of 100 consecutively ascertained PD patients selected only for the absence of mood fluctuations. The second control group consisted of 70 consecutively ascertained PD patients with motor fluctuations but no mood fluctuations. All control subjects were evaluated in a similar manner to the cases. The first 44 subjects in the motor fluctuator control group were included in the consecutively ascertained control group.

Statistical Analysis

Age at onset and duration of disease were compared in the mood fluctuators and control subjects with a two-tailed, unpaired t-test. The distributions of the Hoehn and Yahr stage in the three groups were compared by using a Mann-Whitney U test. We used a chi-square analysis to compare the frequency of individual clinical features between control subjects and mood fluctuators. A Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons: all P-values obtained from comparison of clinical features were multiplied by 9 in the comparison of mood fluctuators and sequentially ascertained control subjects and by 4 in the comparison of mood fluctuators and motor fluctuators. To compute logistic regression models in the comparison of motor and mood fluctuators, we used SPSS version 7.5 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), using as dependent variables presence or absence of psychosis, dementia, or clinical depression. Age at onset and duration of illness were entered first, and the question of interest was the statistical significance of the residual effect of group (mood fluctuators vs. motor-only fluctuators), reported as estimated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS

We identified 70 patients with clinically significant mood fluctuations corresponding to their motor “off” or “on” states. This represented 6.6% of all parkinsonian patients evaluated during the five-year period covered by the study.

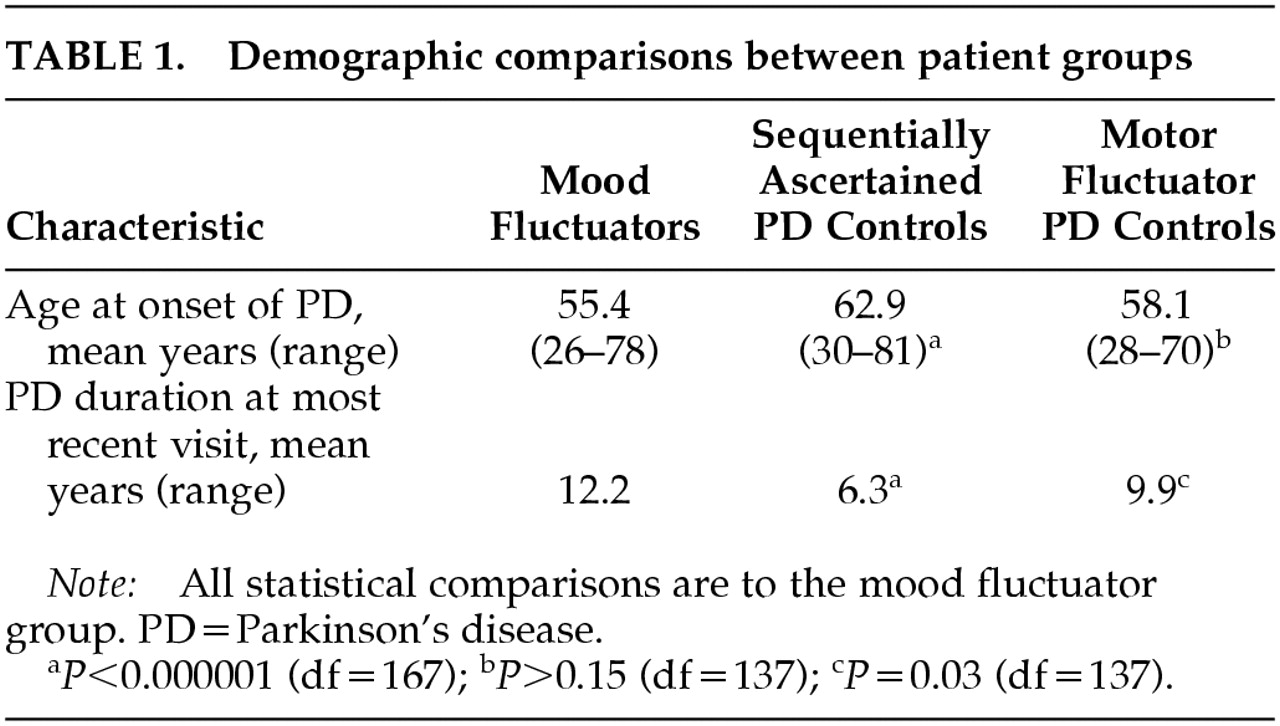

Patients with mood fluctuation developed PD symptoms earlier than the sequentially ascertained control subjects but not the motor fluctuator control subjects, and they had a longer duration of disease than either control group (

Table 1). There were no differences between mood fluctuators and either control group in gender or in disease severity as measured by the modified Hoehn and Yahr scale.

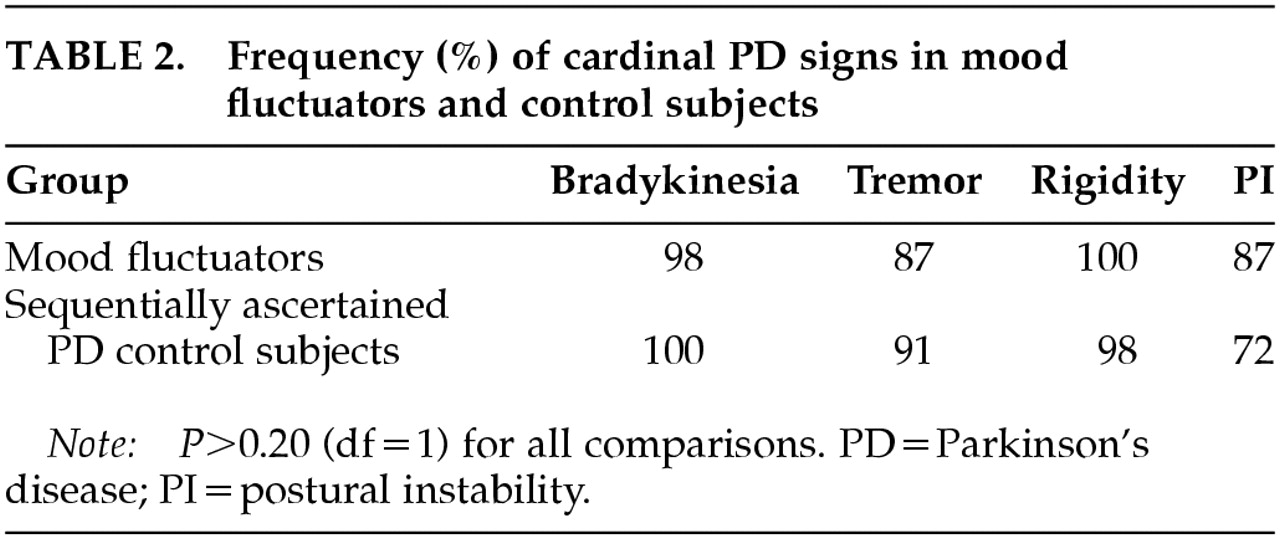

There was no significant difference in the frequency of tremor, rigidity, or bradykinesia between the mood fluctuators and consecutively ascertained control subjects. There was a trend toward increased frequency of postural instability in the mood fluctuators, but this difference was not significant after accounting for multiple comparisons (

Table 2).

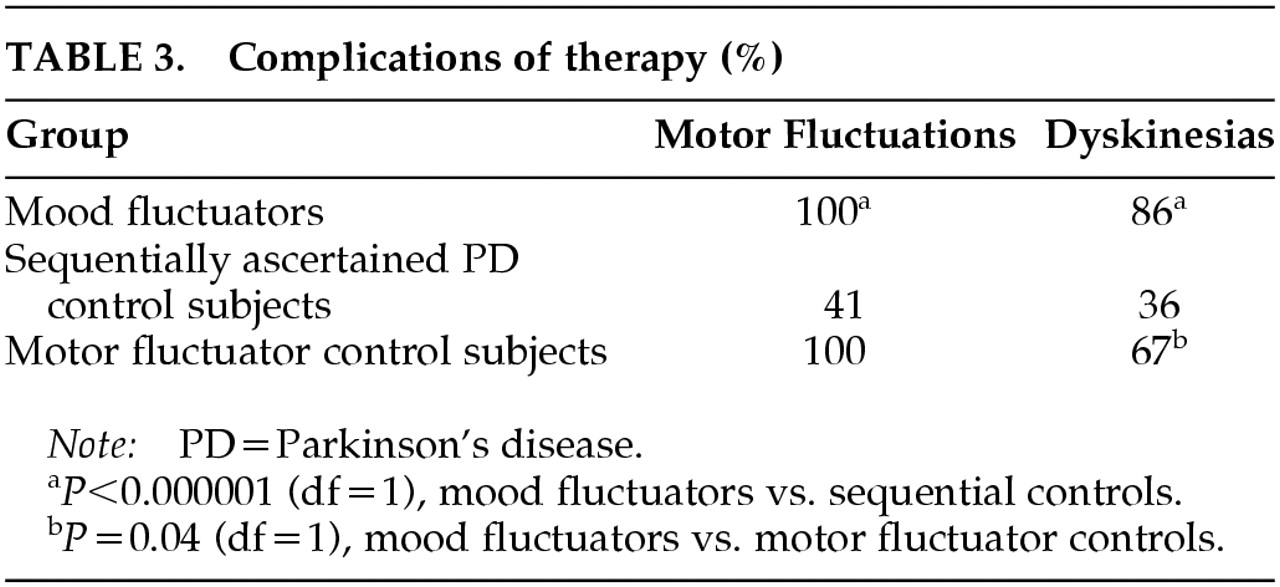

All 70 patients with mood fluctuations also had fluctuations of motor response to levodopa. Mood fluctuations occurred in either the “on” or “off” states and included off-period anxiety (81%), off-period depressive symptoms (63%), and on-period hypomania (24%). There was a significant association between motor and mood fluctuations in the mood fluctuators when compared with the sequentially ascertained control subjects. (

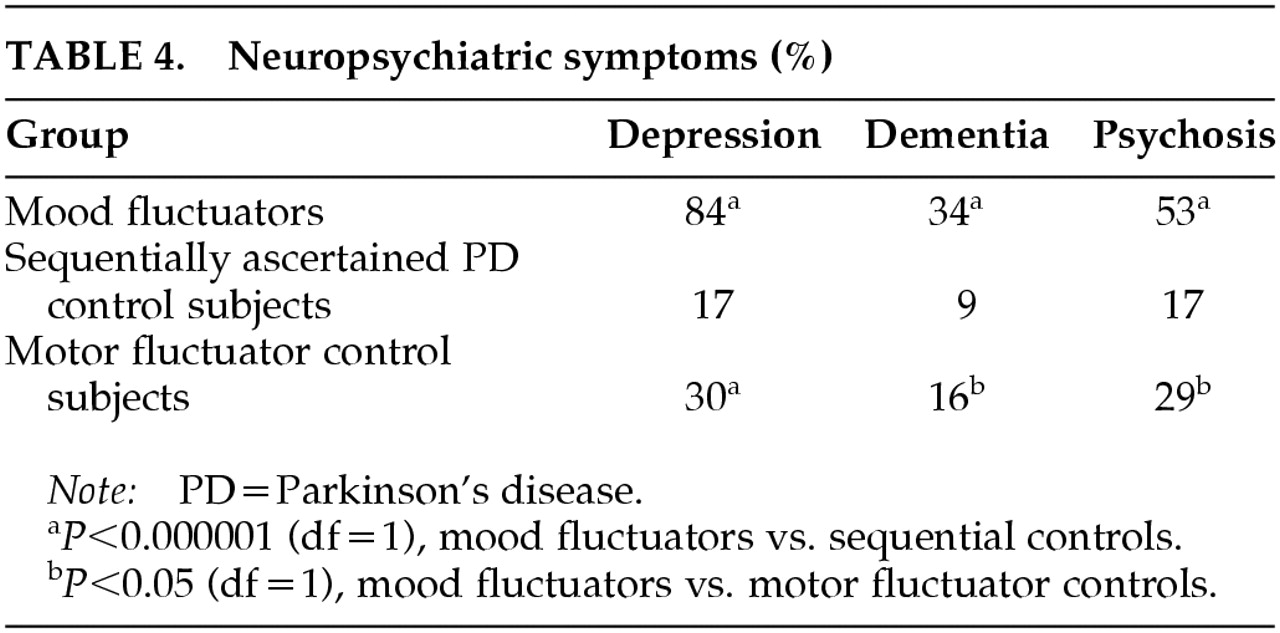

Table 3). Dementia, nonfluctuating clinical depression, and psychosis were significantly associated with mood fluctuations in the mood fluctuators when compared with sequentially ascertained control subjects (

Table 4).

To determine if the presence of motor fluctuations accounted for the association of dementia, depression, and psychosis in patients with levodopa-related mood fluctuations, we compared the frequency of these neuropsychiatric complications in mood fluctuators with their frequency in the group of PD patients having only motor fluctuations. Dyskinesias occurred more frequently in mood fluctuators compared with motor fluctuator control subjects (

Table 3). Dementia, nonfluctuating clinical depression, and psychosis were significantly associated with mood fluctuators when compared with motor fluctuator control subjects (

Table 4). These associations remained significant after correcting for age at onset and duration of disease, as shown by the following odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) for presence of each syndrome in patients with mood fluctuations versus patients with only motor fluctuations: psychosis, 2.45 (1.18–5.09); dementia, 3.24 (1.35–7.81); and clinical depression, 12.33 (5.32–28.56). Thus, even after we accounted for age at onset, duration of illness, and presence of motor fluctuations, patients with clinically important mood fluctuations were substantially more likely than other patients with PD to have experienced psychosis, dementia, or nonfluctuating clinical depression.

DISCUSSION

Our study provides a reasonable estimate of the prevalence of clinically significant mood fluctuations (7%) in a general, clinical PD population. The patients we diagnosed with mood fluctuations were those with clinically apparent change in mood associated with individual levodopa doses; these methods likely underestimate the role of levodopa in persistent mood changes in PD. One study using intravenous levodopa found “off-period” depressive symptoms in 18 of 20 patients after discontinuation of intravenous infusion.

5We found that mood fluctuations occurred more frequently in patients with younger age at onset. This finding may be due to the more frequent association of young-onset disease with motor fluctuations,

25 as supported by our finding that mood fluctuations were strongly associated with motor fluctuations. We also found a strong association between mood fluctuations and psychosis, dementia, and nonfluctuating clinical depression, even when mood fluctuators (who all had motor fluctuations) were compared with other motor-fluctuating patients. This association suggests that mood fluctuations may occur more commonly in patients in whom the PD pathology involves cortical or mesolimbic areas.

26The timing of mood responses to levodopa infusion, the lack of mood fluctuations with placebo infusion, and the lack of similar mood fluctuations in arthritic patients with similar severity of motor fluctuations all suggest that mood fluctuation can be a direct effect of dopamine denervation and levodopa therapy on mood rather than a secondary change associated with relief of motor symptoms.

7–9,27 There is substantial support for the idea that dopamine-influenced neuronal pathways can affect mood.

The most common type of mood fluctuation in our patients was off-period anxiety.

13 Several lines of evidence implicate abnormal dopamine function in anxiety.

28 School phobia is associated with a dopamine transporter allele.

29 Patients with social phobia have decreased binding of striatal dopaminergic ligands, whether assessed with presynaptic or postsynaptic markers,

30,31 despite similar striatal volume.

32 Clinically, acute impairment of dopaminergic neurotransmission produces anxious discomfort as part of akathisia and can cause school phobia in patients with Tourette syndrome.

33 Steady anxiety is common in Parkinson's disease; one study (presented as a conference paper) reported a 58% prevalence of lifetime DSM-IV anxiety disorders in Parkinson's disease patients, compared with 33% in neurological control subjects.

34 Our findings provide additional support for the relevance of dopamine to the control of anxiety.

Dopamine also has well-known effects on the core behavioral symptoms involved in major depression, such as appetitive approach and the association of specific activities with pleasurable reward.

35,36 Animal models of “depression” demonstrate deficient dopaminergic transmission.

37,38 In humans, links between dopamine and idiopathic major depression are modest.

39,40 However, factors related to parkinsonism, prolonged dopaminergic treatment, or both may constitute a permissive state allowing acute decreases in dopaminergic transmission to depress mood. Major depression is common in PD

41,42 and is accompanied by preferential loss of neurons in ventral tegmental area

26 and by defects in prefrontal cortex blood flow and metabolism.

43,44One-quarter of patients with mood fluctuations had clinically significant on-period manic features, including abnormally elevated mood, grandiosity, hypersexuality, impulsivity, or decreased need for sleep. All but one of these patients also had levodopa-induced dyskinesias. These findings are consistent with previous reports associating mania with excess dopaminergic stimulation or hyperkinetic movement disorders.

15,45 PD and its treatment result in a unique combination of a dopamine-deficient untreated state and therapeutic dopaminergic excesses, and our study demonstrates the critical balance required in dopaminergic treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS01808 and NS01898 and by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the American Parkinson Disease Association, the Tourette Syndrome Association, the Charles A. Dana Foundation, and the McDonnell Center for the Study of Higher Brain Function. The work was presented at the 6th International Congress of Movement Disorders, Barcelona, Spain, June 11–15, 2000.