Research suggests that more than one-third of persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders display obsessive and compulsive symptoms

1,2 and roughly 10% to 20% meet full diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

3–6 Given this high rate of comorbidity, it has been suggested that the presence of obsessions and compulsions (OC) may represent a distinct subtype or dimension of schizophrenia.

7,8 Evidence for the existence of this subtype includes findings that OC symptoms in schizophrenia are linked with poorer psychosocial function,

9 earlier onset of illness, and greater service utilization.

2But are OC symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders linked with a particular pattern of symptom or deficits, as one would expect if they represent a unique subtype or dimension of psychopathology? Several studies have reported that the presence of OC symptoms is associated with poorer executive function

10–12 and higher levels of negative symptoms.

3,10 On the other hand, one study has failed to find any association between OC and negative symptoms,

11 and another has reported that OC symptoms predicted less affective flattening in a group of first-break participants.

6 OC symptoms predicted higher levels of positive symptoms in one study,

10 but not in another.

11 OC symptoms have also been linked with heightened levels of emotional discomfort,

10 more severe motor symptoms,

3 and reduced levels of thought disorder.

6 Thus, the data so far suggest that OC symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders are linked with a distinctive clinical picture, but the exact nature of that clinical picture remains unclear.

To address the issue of whether significant levels of OC symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders are linked with a distinctive clinical picture, we examined the association of OC symptoms with three domains of neurocognitive function (vigilance, visual memory, and executive function) and with three domains of symptoms (positive, negative, and emotional discomfort symptoms). Specifically, the neurocognitive test performance and symptom scores of a group with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had significant levels of OC symptomatology were compared with a group without significant OC symptoms. Positive, negative, and emotional discomfort scores were obtained by using the factor-analytically derived Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),

13 and OC symptoms were measured by using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS).

14 An a priori definition was additionally employed to determine whether participants had significant levels of OC symptoms on the YBOCS.

It was predicted that participants with significant levels of OC symptoms would demonstrate greater impairments in the domains of executive function, vigilance, and visual memory. Each of these domains has been uniquely linked with OCD in non-schizophrenia samples.

15–17 Thus, we reasoned that overlap in the structural and functional abnormalities associated with schizophrenia and OCD

18,19 could result in a type of pathophysiological “double jeopardy” with heightened deficits in each area. It was secondly predicted that the OC group would have higher levels of negative, positive, and emotional discomfort symptoms. Here we reasoned that negative symptoms would be heightened in the OC group because of the hypothesized co-occurrence of neurocognitive deficits in the OC group and because of the potential of OC symptoms to augment withdrawal by virtue of their restriction of activity, movement, and interest.

20 We reasoned that the OC group might have more severe positive symptoms because responding to delusions or hallucinations in an obsessive or compulsive manner could increase the influence and intransigence of those symptoms. We lastly anticipated the group with significant OC symptoms would have higher levels of emotional discomfort because of the inherently distressing nature of obsessions and compulsions.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 53 males and 10 females with DSM-IV diagnoses of schizophrenia (n=42) or schizoaffective disorder (n=21) consecutively enrolled in a larger study of the benefits of vocational rehabilitation for persons with schizophrenia. The mean age was 42.2 (SD=9.01) and the mean education level was 13.8 (SD=4.29) years. Participants had a mean of 9.4 (SD=11.90) lifetime hospitalizations, with the first occurring on average at age 24 (SD=7.34). All were initially recruited from an outpatient psychiatry clinic at either a Veterans Affairs Medical Center or a community-based mental health center. All participants were in a postacute phase of illness, as defined by having no hospitalizations or changes in medication or housing in the month prior to entering the study. Excluded from the study were participants with a history of closed head injury or mental retardation.

Instruments

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

21,22 is a reliable 30-item rating scale completed by clinically trained research staff at the conclusion of chart review and a semistructured interview. For the purposes of this study, the PANSS factor-analytically derived positive, negative, and emotional discomfort components were used.

13The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

14 is a rating scale in which the interviewer is asked to review a list of obsessions and compulsions with the participant and then rate 1) the time spent on, 2) interference from, 3) distress from, 4) resistance to, and 5) control over symptoms. Items are summed to provide a total score. Good to excellent interrater reliability has been found among samples with OC disorder.

23The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST)

24 is a neuropsychological test sensitive to impairments in executive function. It asks participants to sort cards that vary according to an unarticulated matching principle that changes after a certain number of correct responses. For the present study we used four scores: number of categories correct, percentage of perseverative errors, percentage of nonperseverative errors, and number of “other” responses, or responses that do not conform to any possible matching principle.

The Visual Reproduction Test Immediate Recall (VRT)

25 is a subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised that assesses visual memory by asking participants to reproduce four drawings immediately after viewing them. A single score is derived that reflects the number of correctly reproduced details.

The Continuous Performance Test (CPT)

26 is a test of sustained attention that uses a 0.87-second presentation of capital letters on a 14-inch screen with a 0.17-second interstimulus interval. In this study, participants pressed a response button each time the letter

X was followed by the letter

A. The total duration of the task was 5 minutes. For the purposes of this study two scores were used: “hits” or correct responses and “false alarms” or instances when participants responded to a stimulus that was not

X followed by

A. Hits and false alarms in this study were significantly correlated (

r=0.27,

P<0.05).

Procedures

After giving informed consent, participants completed a testing and interview battery that included a chart review, participant report of psychiatric history, and the PANSS and YBOCS interviews. Following the completion of these interviews, participants were administered the WCST, VRT, and CPT. Interview and testing were conducted or supervised by a clinical psychologist. Raters and testers were blind to hypotheses.

Participants were categorized as having significant levels of OC symptoms if their YBOCS total score equaled or exceeded 17. The cutoff score of 17 was chosen by taking 22, which was the average mean YBOCS score for persons with schizophrenia and OCD as reported in recent publications,

3,4,6,10,12 and subtracting from it the mean standard deviation reported in those studies, which was 5 (i.e., 22–5=17). Applied to our sample, the resultant cutoff score of 17 placed 11 (17%) of the participants in the OC group. The mean YBOCS score of the OC group was 22 (SD=4). Of the 52 members of the non-OC group, 41 had YBOCS scores of 0, and 11 had scores between 2 and 15. The mean YBOCS score in the non-OC group was 2.9 (SD=5).

RESULTS

Eleven participants were classified as having significant OC symptoms (the OC group) and 52 as not having significant levels of OC symptoms (non-OC group). Comparisons of participant demographics in the OC and non-OC groups revealed no significant differences between groups on age, education, gender, lifetime number of hospitalizations, or age at first hospitalization. Comparisons of participants with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder revealed no differences on YBOCS scores, OC grouping, or neurocognitive testing. Intercorrelations between neurocognitive measures revealed that CPT scores were not significantly correlated with performance on the WCST or VRT. Performance on the VRT was negatively correlated with percentage of perseverative errors (r=–0.20, P<0.05) but was not related to other WCST measures. PANSS component scores were not significantly correlated with neurocognitive measures.

To examine links with neurocognitive function, a multivariate analysis of covariance was performed comparing WCST, CPT, and VRT performance of the OC and non-OC groups, controlling for age and education. As predicted, there was a significant overall difference in test performance between groups (

F=3.5, df=7,53,

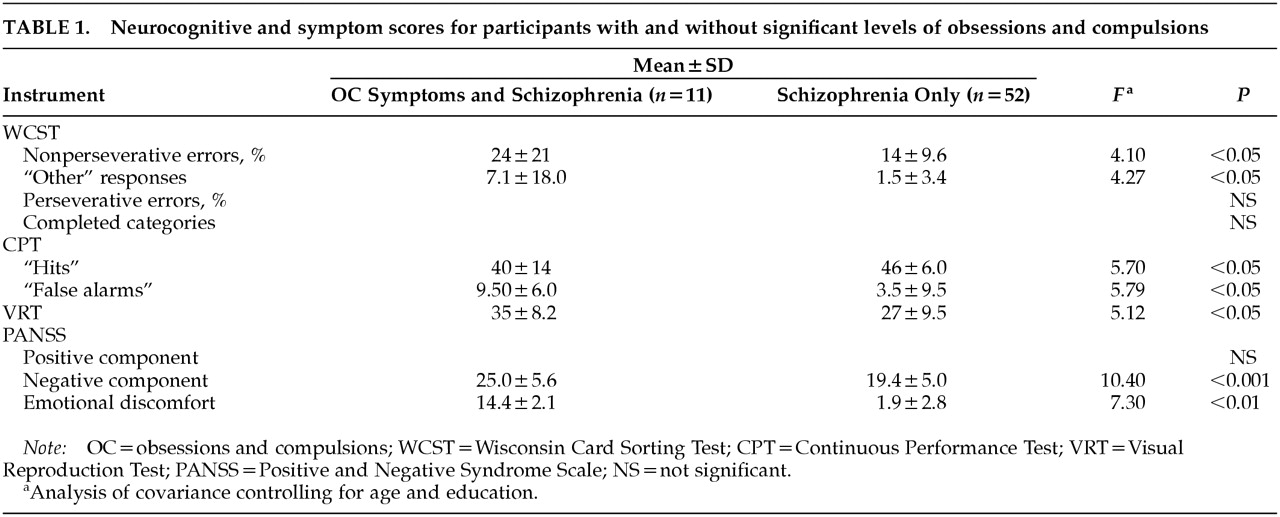

P<0.05). As presented in

Table 1, follow-up analyses of covariance revealed that relative to the non-OC group, the OC group had a higher percentage of nonperseverative errors on the WCST, more “other” responses on the WCST, fewer correct on the CPT, and more false alarms on the CPT. Contrary to predictions, the OC group performed better than the non-OC group on the VRT.

To examine symptom differences, a multivariate analysis of variance was conducted comparing PANSS component scores. This analysis revealed significant overall group differences (

F=2.91, df=5,57,

P<0.05), with individual analysis of variance indicating that the OC group had significantly higher levels of negative and emotional discomfort symptoms than the non-OC group (see

Table 1). No differences were found on the positive component. Although no predictions were made regarding the two other PANSS components—the cognitive and excitement components—groups were compared on these scores for exploratory purposes. None of these analyses revealed significant group differences.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with literature suggesting that OC symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders may represent either a subgroup or an orthogonal dimension of psychopathology, participants with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and OC symptoms had a significantly different profile of symptoms and neurocognitive deficits than participants without significant OC symptoms. In findings that replicate previous work,

3,10–12 the OC group had graver deficits in executive function and higher levels of negative symptoms and emotional discomfort. Examining two other neurocognitive domains, we found that the OC group had more severe impairments in vigilance but lesser deficits in visual memory. Levels of positive, cognitive, and excitement symptoms were not found to differ between groups.

Taken together, these results suggest that OC symptoms are of clinical significance in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In particular, results indicate that the OC group may have difficulties sustaining attention and may tend to respond to evolving environmental challenges in a relatively disorganized and haphazard manner, contributing to deficits in social, occupational, and community function. Notably, there was an unexpected finding. The visual memory of the OC group was superior to that of the non-OC group. This is puzzling and may suggest that whereas OC symptoms interfere in tasks requiring a sustained focus and response to shifting demands, OC phenomena could assist persons with schizophrenia in acquiring and storing visual information. As is the case with all unexpected findings, replication and further study are necessary before any conclusions can be drawn.

The links demonstrated here between OC symptoms and clinical and neurocognitive features of schizophrenia lastly raise the question of causality. How should we explain the relationships observed in our sample? There are at least three general hypotheses. First, the presence of OC symptoms in schizophrenia could represent a single diagnostic entity complete with its own pathophysiology and course, which, as suggested by Zohar,

27 might be best labeled schizo-obsessive or schizo-anxious disorder. Second, obsessive-compulsive symptoms could represent a dimension of symptomatology that varies independently of other features of illness but does not represent a distinct entity. Third, OC phenomena in schizophrenia may represent the presence of comorbid diseases that augment and exacerbate one another. Given that visual memory is generally impaired in OCD and that we found that the visual memory of our OC group was superior, the data do appear to be clearly at odds with the hypothesis that OC in schizophrenia is a reflection of comorbid disease processes. Further research is needed, however, that assesses symptoms and cognitive and psychophysiological functioning repeatedly in a longitudinal design before these issues of causality can be addressed definitively.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. Participants were generally in their forties and interested in rehabilitation. It may be that a different relationship exists between OC symptoms and clinical features of illness among persons in earlier stages of illness or those who do not seek or need rehabilitation. In addition, the same raters administered both the PANSS and YBOCS, and thus ratings of obsessions, compulsions, and symptoms of schizophrenia were potentially subject to rater bias. Further research is necessary with varying populations and in which rating of obsessions and compulsions are made blind to rating of other symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Rehabilitation, Research, and Development Service: “Effects of Work Activity and Cognitive Rehabilitation on Schizophrenia,” Morris Bell, Ph.D., Principal Investigator.