Psychiatric medications are used frequently to control different behavioral manifestations of Alzheimer's disease (AD). The effectiveness of these treatments has significant implications for the burden the disease puts on the patients, their caregivers, physicians, and society. Practice guidelines usually recommend using behavioral and environmental approaches first, followed by various medications.

1 However, there is still considerable debate about the selection and effectiveness of various classes of medications to treat abnormal behavior (e.g., agitation, aggression, psychosis).

2–7Controlled trials conducted in the 1980s showed that no single antipsychotic or non-antipsychotic drug was best to treat abnormal behavior in patients with dementia, and drugs were only modestly superior to placebo.

8,9 This controversy continued through the 1990s, with Teri et al.

10 finding no significant differences among haloperidol, trazodone, behavioral management techniques, and placebo to treat agitation in AD. More recently, other studies did find that typical and atypical antipsychotics, as well as the new generation of antidepressants, are better than placebo for controlling agitation and aggression in AD patients.

5,11–14While the debate about the effectiveness of psychiatric medications, and the best ways to use them in the context of dementia, continues among researchers, little is known about how community physicians (including psychiatrists, neurologists, and primary care physicians) approach the treatment of psychiatric symptoms in AD. What is more important, little is known about how primary care physicians have incorporated recent scientific advances into their clinical practice. In this study, we examined how community physicians have changed their pattern of use of psychiatric medication over the past 20 years, with special emphasis on antidepressants, antipsychotics, and sedatives/hypnotics/anxiolytics (SHA).

RESULTS

Of the 1,155 patients with a diagnosis of probable AD, 330 (28.5%) took psychiatric medications; 225 (19.5%) used antidepressants, 93 (8%) antipsychotics, and 76 (6.5%) SHA. Overall, there was an increase in the number of patients taking psychiatric medications from 1983 to 2000 (1983–1989, 23%; 1990–1995, 25%; 1996–2000, 37%; χ2=22.7, df=2, P<0.0001)

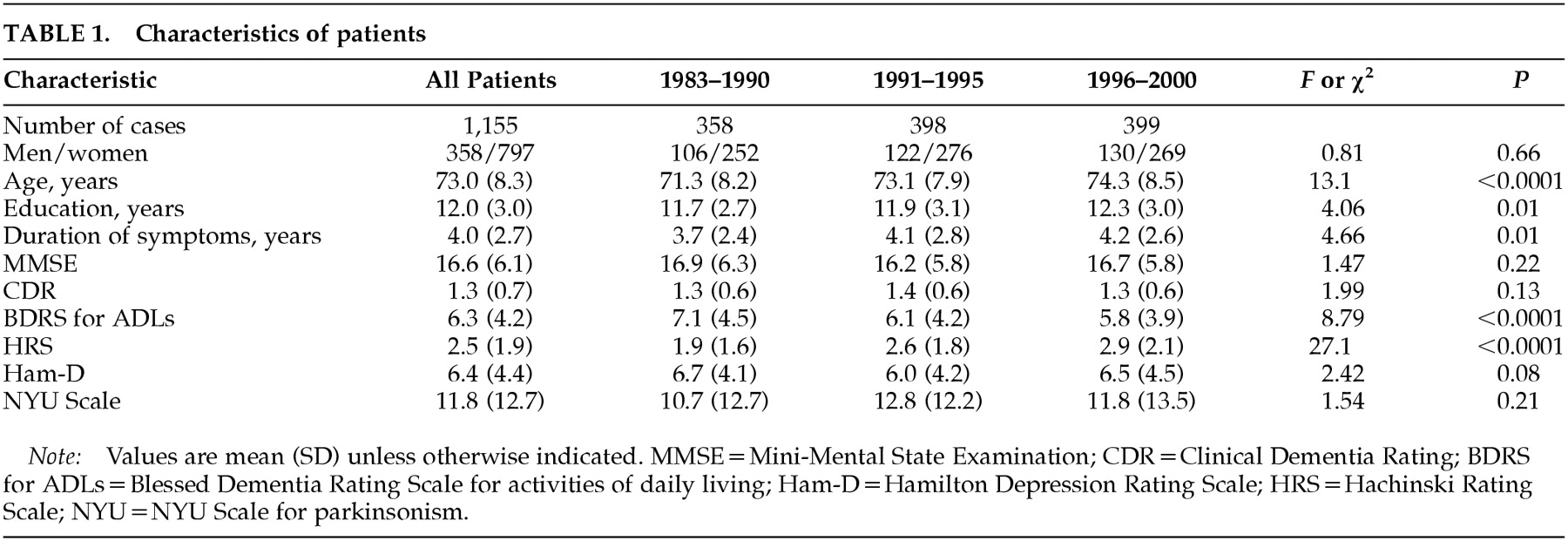

The demographic and neuropsychiatric characteristics of the patients per group are shown in

Table 1 as a function of their date of study entry. Patients enrolled between 1983 and 1990 were younger and had a shorter duration of the symptoms of dementia, higher (i.e., worse) BDRS

26 scores for activities of daily living, and lower Hachinski Ischemic Rating

28 scores than those enrolled in 1991–1995 and 1996–2000. No statistical differences were noted among groups for scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination,

29 Clinical Dementia Rating,

30 Ham-D,

25 or NYU Scale for Parkinsonism.

31Psychiatric Symptoms

The frequency of major depression, aggression, and hallucinations was not statistically different between 1983 and 2000. By contrast, there were more patients with psychomotor agitation, delusions, and sleep disorders in 1991–2000 than in 1983–1990 (

Table 2).

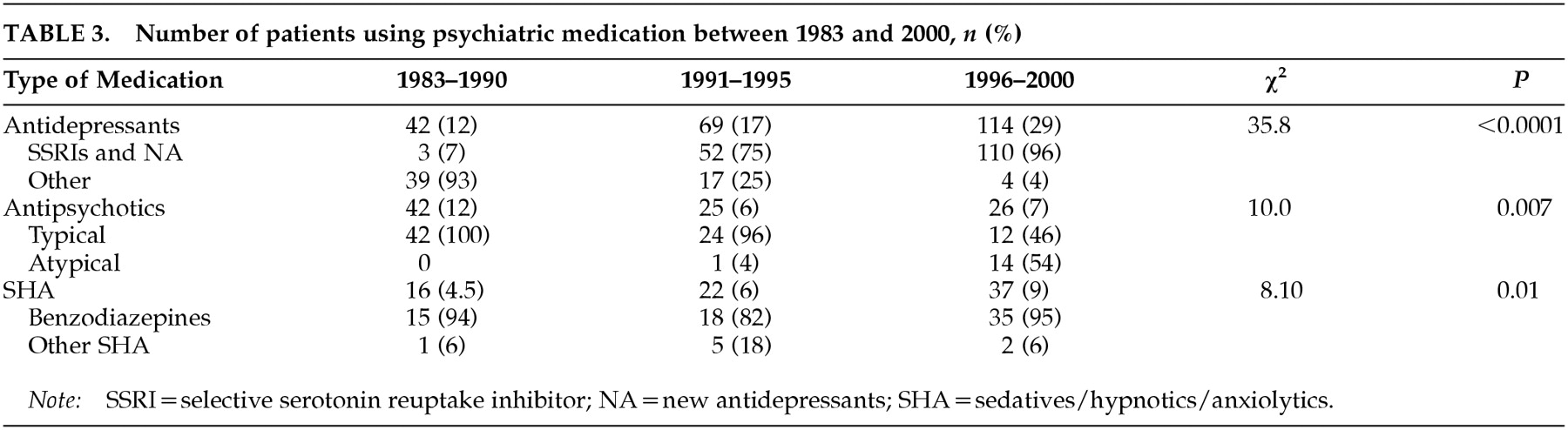

Use of Psychiatric Medication

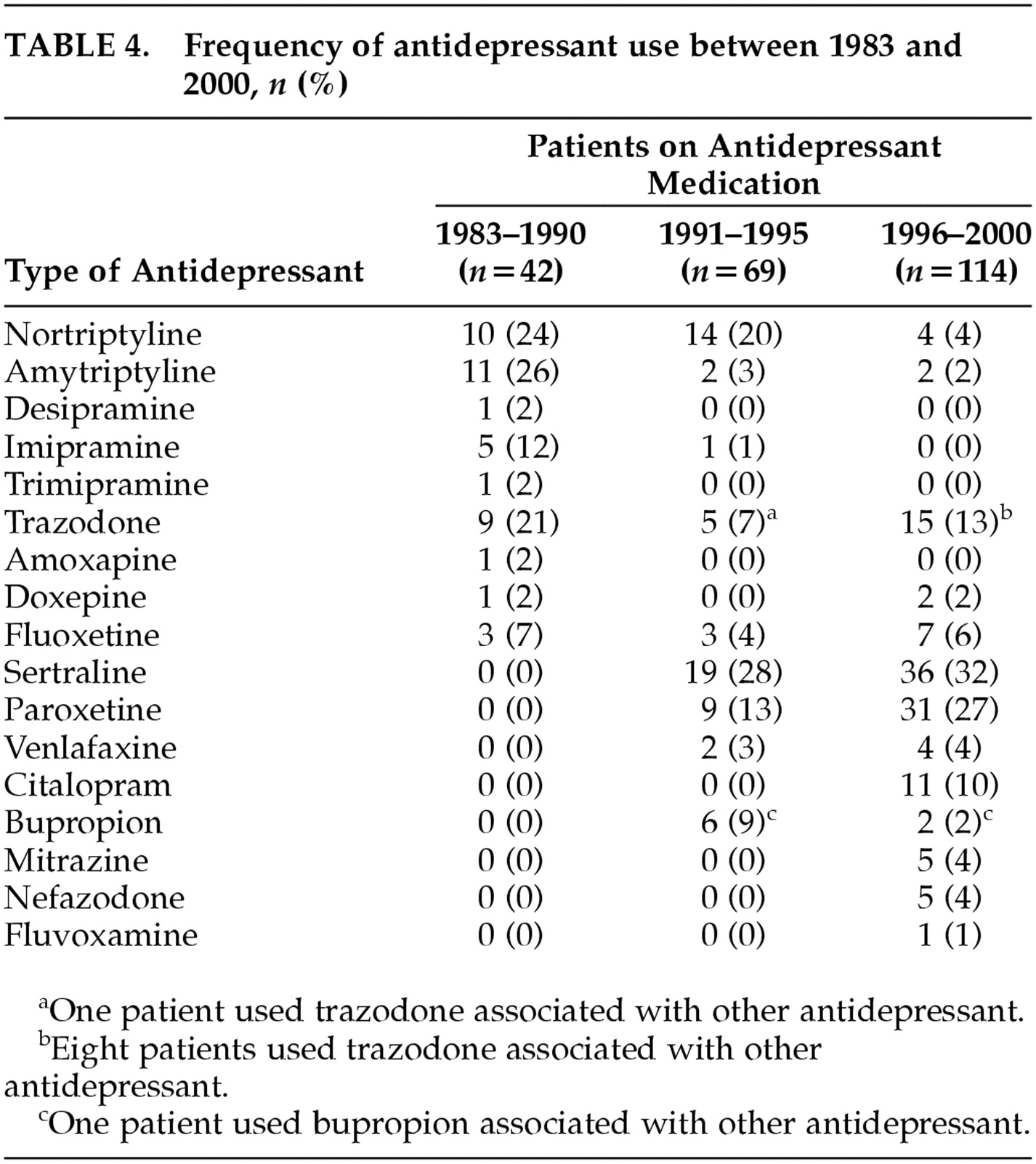

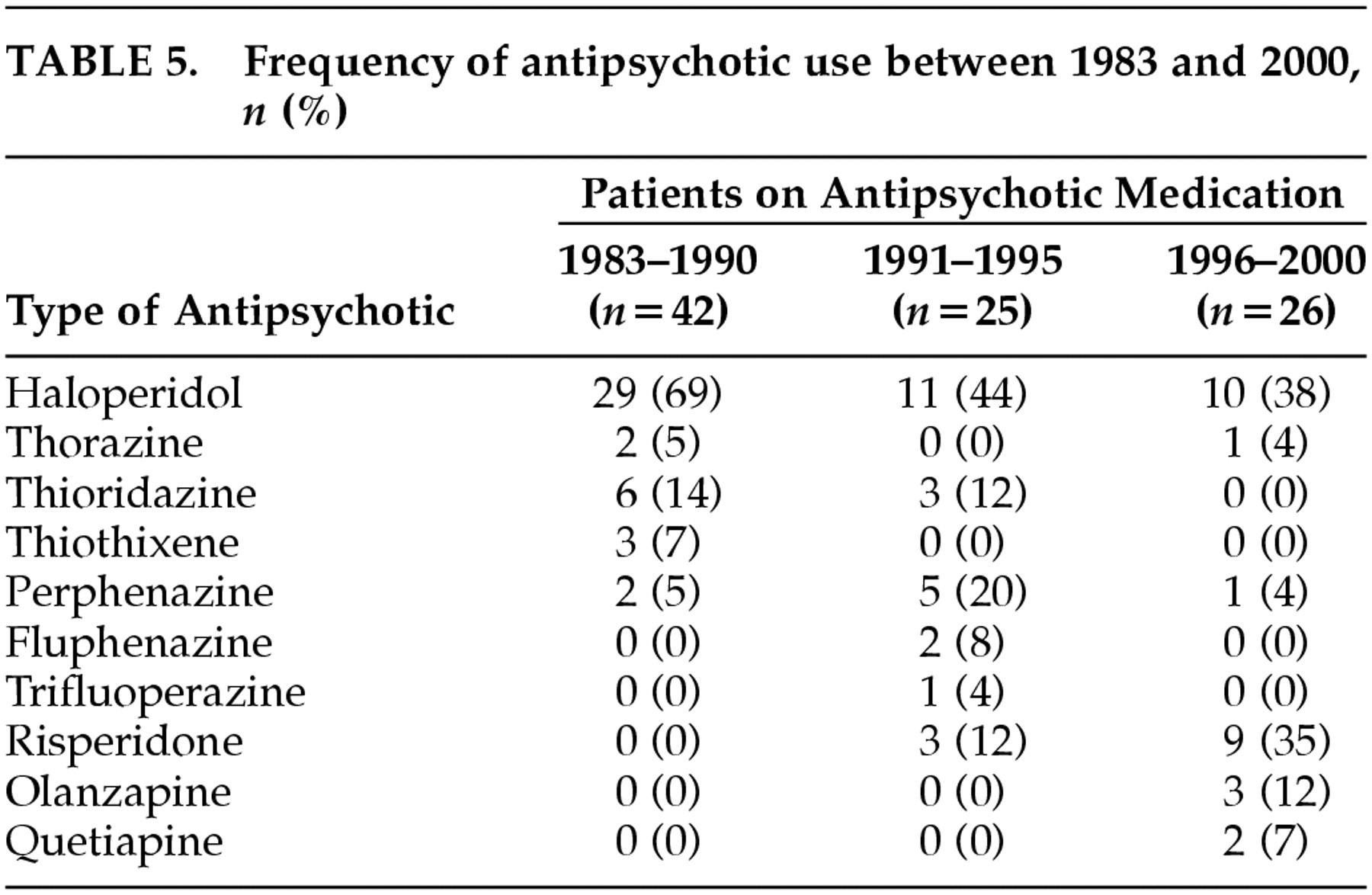

Table 3 shows the overall pattern of use of psychiatric medication over the past two decades. In 1983–1990, fewer patients were using antidepressants and more were using antipsychotics than in the 1991–1995 and 1996–2000 periods. In 1996–2000, more patients were taking SHA than in 1983–1990 and 1991–1995, and the proportion of patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and new antidepressants (NA; e.g., nefazodone) had increased since 1991. Notably, the proportion of patients taking atypical antipsychotics in the 1996–2000 period was similar to the proportion taking typical antipsychotics. The data on specific medications taken during the different time periods are shown in

Tables 4,

5, and

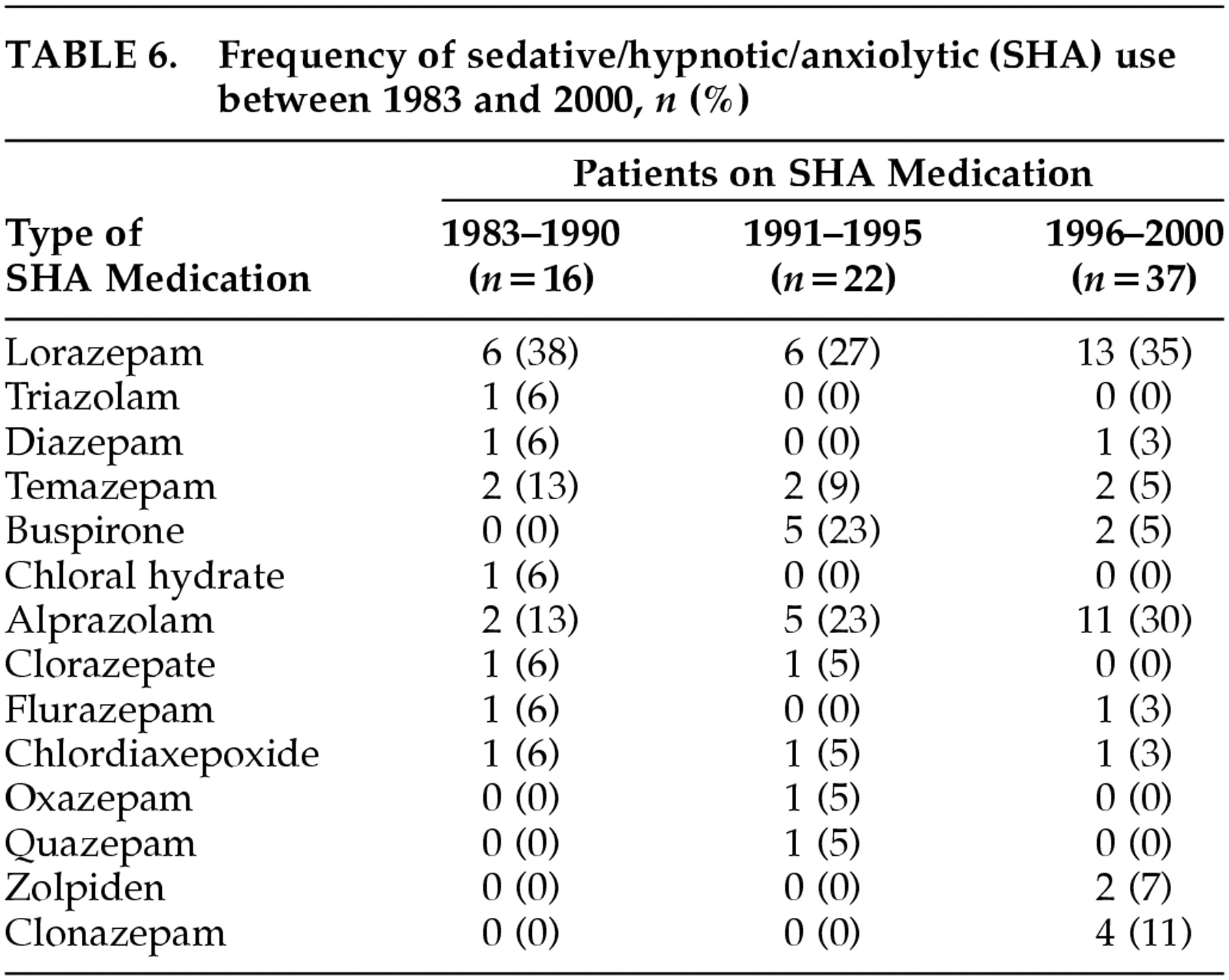

6.

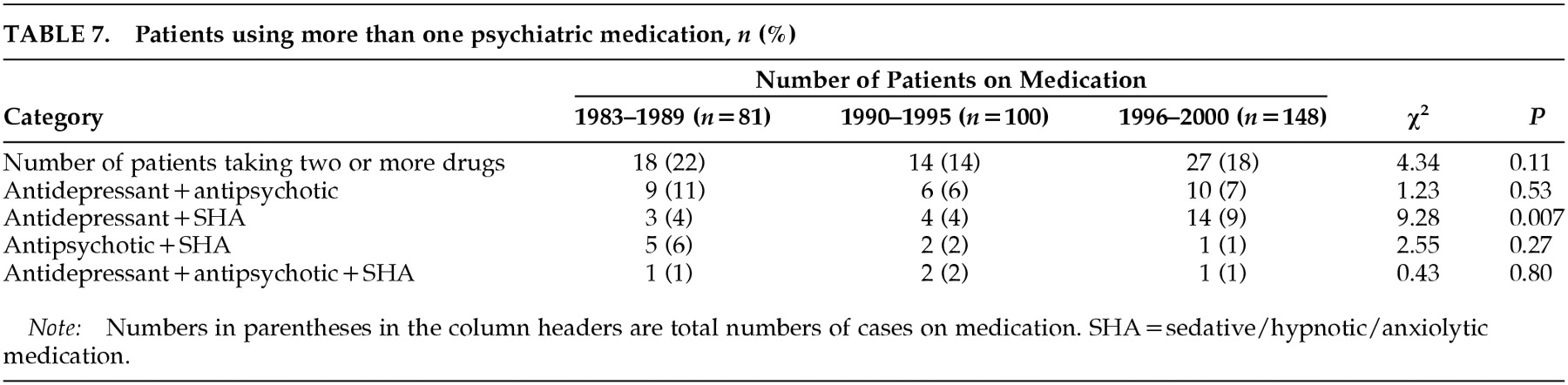

Table 7 shows the proportion of patients who were treated with more than one psychiatric drug. There were more patients using antidepressants with SHA in the 1996–2000 period than in the 1983–1990 and 1991–1995 periods.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that 28.5% of the studied patients with probable AD were taking some psychoactive medications at the time of entry into our registry. Of all the patients, 19.5% used antidepressants, 8% antipsychotics, and 6.5% SHA. However, the pattern of medications prescribed by community physicians was different in the 1990s compared with the 1980s, showing decreased use of antipsychotics and increased use of antidepressants and SHA. These findings are consistent with those of Mendez et al.,

32 who found in about 1990 that 7% of the AD patients used antidepressants, 11.5% antipsychotics, and 7% SHA.

The increased use of antidepressants in AD may reflect evidence that these agents can treat syndromes other than depression, such as psychosis, agitation, and sleep disturbances.

5,12,19 As noted here, while the frequency of major depression among the studied patients remained stable from 1983 to 2000, the frequency of psychosis, agitation, and sleep disturbances increased, and there was an associated increased in antidepressant use. Antidepressants can be used for longer periods of time and with less risk of the development of extrapyramidal signs than antypsychotics.

17 Furthermore, although old (e.g., tricyclic) and new antidepressants seem to be equally efficacious in the treatment of depression, there are differences in their metabolism (cytochrome P450 inhibition), their potency-inhibiting neurotransmitter reuptake, and their potency for blocking neurotransmitter receptors. In particular, antimuscarinic effects are substantially lower with SSRIs and NA in comparison to tricyclics, with a decreased risk for cognitive toxicity in AD subjects. These differences seem to be well understood by community physicians, and 96% of the patients treated in 1996–2000 were on SSRIs or NA, although a small group was still on traditional antidepressants, perhaps reflecting a treatment failure of the newer antidepressants. This change in the pattern of SSRIs use has also been reported in population studies: Ganguli et al.

33 found that 84.6% of the participants taking antidepressants were on tricyclics and 2.6% on SSRIs in 1987, whereas in 1996, 45.5% were on tricyclics and 36.4% on SSRIs.

Even though the new antipsychotic medications have fewer extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, there has been an overall reduction in the use of any antipsychotics over the past 20 years. This may be explained, in part, by the increased use of antidepressants in the treatment of abnormal behavior in AD, at least in patients with mild/moderate stages. However, the decrease in antipsychotic use (from 12% to 7%) is more than offset by the increasing use of antidepressants (from 12% to 29%). A change in the pattern of drug use to treat behavioral problems does not fully account for this increase, suggesting that there might also be an increase in the use of antidepressants to treat mood disorders among patients with dementia.

Several studies have reported that new antidepressants (e.g., SSRIs)

5,14 as well as typical

11 and atypical

12,13,15,16 antipsychotics are effective in the treatment of agitation and aggression in AD. However, whether antidepressants are better than antipsychotics in the treatment of psychiatric symptoms in AD is under debate. Sultzer et al.

34 found no differences between the efficacy of haloperidol and trazodone in the treatment of agitation in AD patients.

Despite the recent advances in the development of new antipsychotics, 47% of the patients in the 1996–2000 period continued using typical antypsychotics. A possible explanation is that physicians are more comfortable treating patients with typical antipsychotics and that these medications have wider dosing ranges and more formulations than atypical antipsychotics (i.e., the availability of concentrates, injectables, tablets, sprinkling preparations, and the option of incorporating medication into food and drink).

SHA are the oldest and best established treatments for abnormal behavior and insomnia in demented and nondemented patients, and guidelines for the use of SHA in AD recommended short-term use of short-acting benzodiazepines.

35 However, SHA have proven deleterious effects in elderly patients. Benzodiazepines can produce amnesia,

36 increase the risk of falls and death,

37,38 and increase costs of medical treatments.

39 We have reported that the use of SHA is associated with reduced time to death in probable AD patients.

40 Despite robust data that indicate SHA should be used judiciously in AD patients, their use has increased over the past 20 years in this cohort. Indeed, we found an increased SHA use during the observation period (from 4.5% in 1983–1990 to 9% in 1996–2000), consistent with recent observations from population studies showing an increase from 2.2% in 1987 to 10.7% in 1999.

41It is common to use more than one psychiatric medication, especially in patients with severe behavioral symptomatology, although there are no guidelines that recommend the best approach in these cases. In this case series, approximately 19% of the patients taking psychiatric drugs were using two or more drugs. Interestingly, there was an increased tendency to use antidepressants and SHA together, which may reflect the reduced sedative effects of SSRIs and NA relative to tricyclics.

This is an observational study on a referral cohort of AD patients, and thus our results may be biased toward a specific subgroup of patients. However, populations studies have reported similar findings in terms of increased antidepressant and SHA use over the past two decades.

33,41 Another factor that may have affected our results is the change in the characteristics of the patients over these referral periods. As shown here, we examined patients with fewer disruptive behaviors in 1983–1990 than in 1991–2000, although they did not have significant differences in cognitive functions (MMSE, CDR scores). An increasing tendency to prescribe antidepressants for these behaviors could explain, in part, the better functional (BDRS) scores observed in the 1991–2000 period.

There have been significant advances in psychopharmacology over the past two decades. Since the 1980s, we have witnessed the introduction of a great number of successful antidepressants, and from the mid-1990s, the introduction of atypical antipsychotics. By contrast, the introduction of new sedatives/hypnotics/anxiolytics has not been as successful as other medications, although some SHA with shorter half-life have become available (e.g., alprazolam). These new medication opportunities are reflected in the way that physicians treat their patients, especially with the use of antidepressants. However, more controlled trials will be necessary to determine when an antidepressant is better than an antipsychotic for specific symptoms. There is a need for better dissemination of the advantages of atypical antipsychotics over conventional neuroleptics in elderly patients, and for the development of guidelines for combinations of neuropsychiatric medications. The expectations of families and patients have risen over the past 10 years as advances in AD treatment have been disseminated to the public. Direct-to-consumer advertising for many of these medications has created educated consumers who know what to “ask for.” These changes will also have an effect on the prescribing habits of physicians treating AD.