As noted in a recent historical review,

1 euphoria and related neurobehavioral phenomena have been observed in multiple sclerosis (MS) since Charcot

2 first noted that many patients exhibit a peculiar “cheerful indifference without cause.” More recent work

3,4,5 suggests that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesion burden and atrophy are associated with dementia and euphoric personality change. However, while cognitive impairment in MS is well understood, there remains much uncertainty about the prevalence and scope of the euphoria syndrome.

Two recent studies attempted to measure personality and behavior change using reliable and validated instruments. Our group

6 employed the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI),

7 a standardized questionnaire based on the widely recognized Five Factor Model of personality.

8,9,10 Compared to healthy controls, cognitively impaired MS patients had higher degrees of neuroticism and lower degrees of extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Regression models demonstrated that informant reported decrements in altruism, a component of agreeableness, and conscientiousness were associated with cognitive (especially executive function) impairment. Similar personality changes were previously identified in patients with Alzheimer's disease.

11,12 In a study of 44 MS patients, Diaz-Olavarrieta and colleagues

13 found that behavioral symptoms, assessed with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) of Cummings,

14 are more common in MS (95%) than in controls (16%). Patients exhibited depression most commonly, but euphoria and disinhibition were also observed.

Unfortunately, these studies were limited by small sample sizes, selection bias, and failure to account for personality, depression and behavior change in the same analysis. Thus, differences of opinion remain regarding the prevalence and scope of this neurobehavioral syndrome. Designed to address methodological problems in prior work, this study endeavored to (a) develop criteria for identifying a euphoria syndrome in MS; (b) determine the frequency of the syndrome in an unselected sample; and (c) identify other disease and psychological variables that are associated with the syndrome.

RESULTS

Descriptive Data and Group Comparisons

Most participants were women (67% MS, 60% control) and Caucasian (86% MS, 100% control). The mean (±SD) ages were 43 (± 8) and 41 (± 8) years, for MS and controls respectively. The mean education level for both groups was 14.6 (± 2) years. Among MS patients, 44 (59%) of the informants were spouses or full-time domestic partners, 10 (13%) were parents, and 21 (28%) were other family members (e.g., siblings) or close friends. These informants had known the patients for an average of 24 (± 13) years. Among control participants, 19 (76%) of the informants were spouses, and 6 (24%) were other family members or close friends. The control informants had known the primary participants for an average of 19 (± 12) years. These characteristics did not differ significantly between the two groups (all p values > 0.6). In addition, NEO-PI and NPI ratings did not differ among informant subgroups (domestic partners, parents, other). Mean disease duration was 12 (± 7) years (range 2–44). Most patients (54% or 72%) had relapsing-remitting disease. The mean EDSS score was 3 (± 2; range 0–7.5).

There were no significant group differences on the NEO-PI. Among MS patients, mean BDI was 9.7 (± 7.4) and mean CES-D was 8.8 (± 6.1). For the control group, these values were 4.9 (± 4.2) and 4.7 (± 3.6), respectively. Mean differences were significant (BDI p = 0.004; CES-D p = 0.003). The two groups also differed significantly on the informant-rated MS Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (p < 0.001), with higher values reported for patients (23.3 ± 13.6) vs controls (13 ± 7.8). On the NPI Caregiver Distress Index, mean distress among MS informants was 7.5 (± 7.2) compared to 1.1 (± 2.2) for controls (p < 0.001).

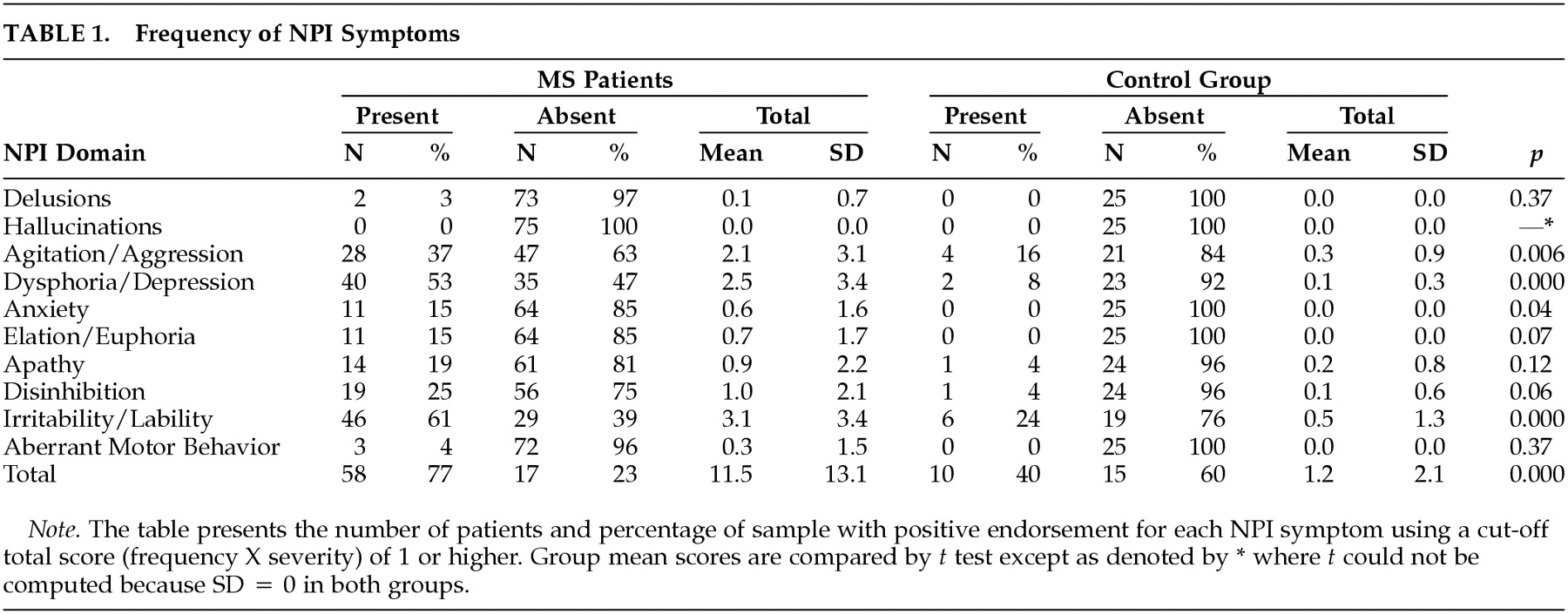

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (

Table 1) were more common in patients. Most (66% or 88%) exhibited at least one behavioral disturbance and 36 patients (as compared to one control) exhibited a “marked” disorder as operationalized by Wood et al (domain score greater than 4).

26 The mean MS NPI Index was 11.5 (± 13.1; median = 6, range 0–54), almost 10 times higher than the control group mean (1.2 ± 2.1,

p < .001). Significant group differences were also apparent on Agitation/Aggression, Dysphoria/Depression, and Irritability/Lability (p < .01).

Factor Analysis of the Behavioral Symptoms in MS Patients

Factor analysis of NPI domain scores yielded a two-factor solution, accounting for 68% of the variance. The first factor contained agitation/aggression, euphoria, disinhibition and irritability/lability and accounted for 40% of the variance (loadings of .85, .87, .78, and .66, respectively). The domains of dysphoria/depression, anxiety and apathy emerged as the second factor, accounting for 28% of the variance (loadings .73, .70 and .73, respectively). The eigenvalues for the two factors were 3.15 and 1.66, respectively. The oblique structure matrix showed essentially the same pattern of item loadings as the orthogonal rotation. As such, two factor scores were calculated from NPI raw data. The first, the sum of the agitation/aggression, euphoria, disinhibition and irritability/lability scores, was labeled euphoria/disinhibition. This factor is descriptive of euphoria patients in the classical literature.

1 The 2

nd factor, labeled dysphoria/apathy, was calculated as the sum of dysphoria/depression, anxiety, and apathy domain scores.

Frequency

Among MS patients, the mean euphoria/disinhibition score was 6.8 (± 8.3), and the mean dysphoria/apathy score was 4.0 (± 5.5). Both were significantly higher (

p < 0.001) when compared to controls (1.0 ± 1.8 and 0.2 ±0.8, respectively). The euphoria/disinhibition factor was operationalized by applying a cutoff score of 16 (four domains × 4), as suggested in prior research.

26 A score >16 was judged to reflect “marked” disturbance. Seven patients, or 9% of the sample, met this standard.

Correlates and Predictors of Behavioral Disinhibition

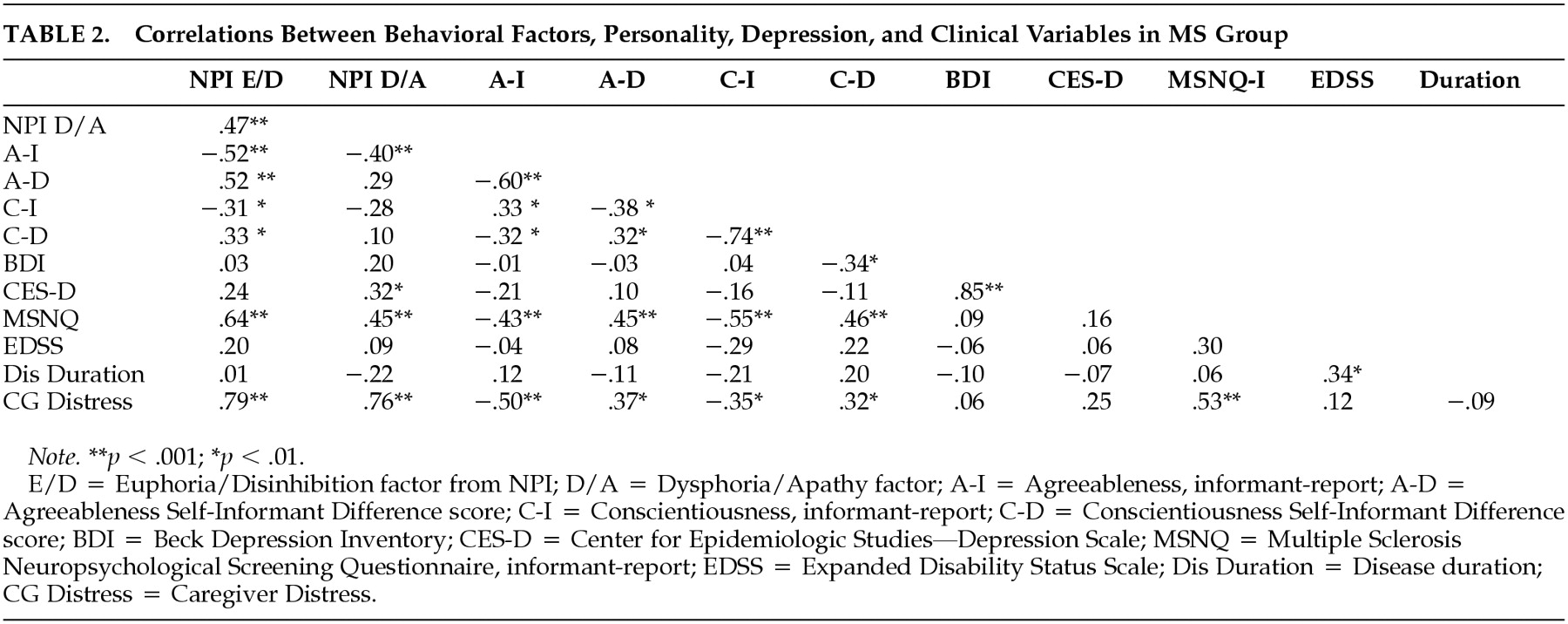

Pearson correlations appear in

Table 2. The following clinical and demographic variables were entered into a stepwise regression model predicting euphoria/disinhibition: age, gender, education level, years informant has known patient, disease course (relapsing vs progressive), disease duration, and EDSS. In this model, only disease course emerged as a significant predictor (

R2 = 0.13,

p = 0.01). A second model was tested with course entered and held in block 1, and the remaining psychological variables from

Table 2 entered stepwise in block 2. Agreeableness and the Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire were retained in the model, explaining 51% of the variance (

p < 0.001).

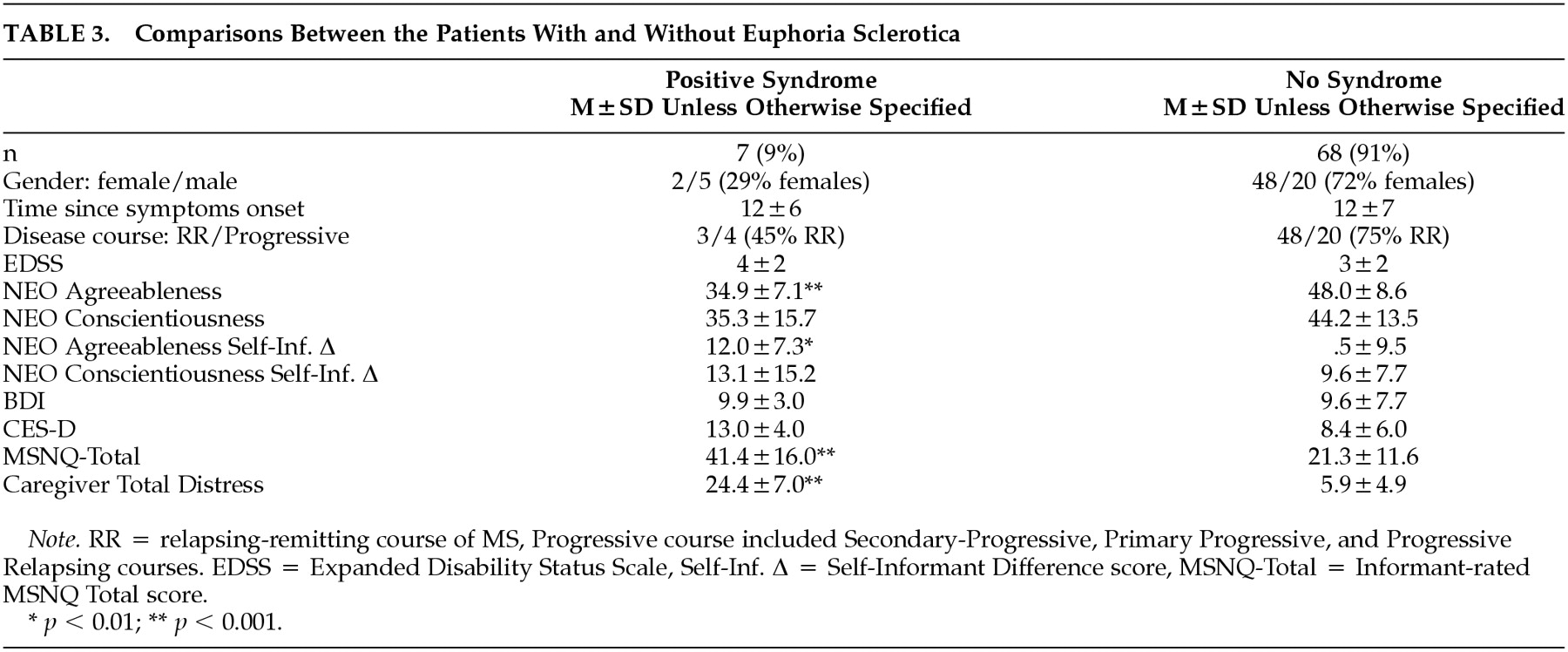

Table 3 presents data from patients with euphoria/disinhibition contrasted against the remaining sample. Note that the syndrome is somewhat more likely to occur in men and that patients with the syndrome are lower in agreeableness and somewhat lower in conscientiousness. Patient-informant discrepancies are higher in the euphoria/disinhibition patients, suggesting diminished insight in this subgroup. Patients with “high” euphoria/disinhibition scores were judged to be more cognitively impaired and to have more distressed caregivers.

DISCUSSION

Euphoria and associated neurobehavioral signs in MS have intrigued clinicians for over a century; but heretofore, the syndrome, originally called

euphoria sclerotica27 had not been operationalized with objective criteria. We used the NPI to measure this construct in 75 consecutive, non-referred MS patients. This euphoria/disinhibition factor was present in 7% or 9% of the sample. These patients were characterized by secondary progressive course, low agreeableness on personality testing, poor insight, and impaired cognition. Caregivers of these patients were markedly distressed, suggesting that this syndrome has deleterious effects on caregiver-patient interactions. Ours is the first study to measure the prevalence of this syndrome in a consecutive, unselected clinical sample, using a valid and reliable psychometric test.

The euphoria/disinhibition factor captures not only euphoria, but other behaviors that have been associated with

euphoria sclerotica such as disinhibition, impulsivility, and emotional lability.

2,27,28,29 Several informants referred to distressing behaviors such as childishness, anger outbursts, and lack of empathy. Elevated euphoria/ disinhibition scores were also associated with low agreeableness which characterizes patients as impatient, inconsiderate, and quarrelsome. Altogether, these traits resemble the syndrome as described in the classic literature.

1 The NPI does not include a measure of unawareness or, in the terms of Charcot, “indifference.” However, the NEO-PI provides an indirect measure of awareness by comparing self- and informant-reports of personality and behavioral tendencies. In healthy volunteers, these discrepancies were minimal. In our previous work,

6 we found that patient/informant discrepancies were associated with executive function deficits in patients. To measure the original construct as described by Charcot, the NPI would have to be complemented by the NEO-PI or some similar measure that compares patient and informant reports of personality and behavior.

We propose that

euphoria sclerotica as defined here is probably neuropsychologically mediated and caused by a combination of strategically located lesions and premorbid personality traits. The syndrome might be explained by white matter lesions causing disconnection of prefrontal cortex and limbic structures. Conversely, gray matter pathology is increasingly recognized in MS

30 and focal pathology to inferior frontal cortex could also account for significant variance in this disorder. Studies investigating MRI correlates of the syndrome are underway.

This study is based on a consecutive series of non-referred patients and in our view, the results represent a reasonable estimate of the prevalence of this syndrome in MS clinic attendees. The frequency may be lower in a random, population based sample. A limitation of this study is the reliance upon informant-ratings. We view this as a necessary evil, given the impracticality of directly observing patients in their natural milieu. In the future, investigators may wish to validate this NPI construct with video recordings of staged social interactions. Validity data supporting the NPI and the NEO-PI notwithstanding, we should consider that factors other than a patient's behavior may influence informant ratings. An additional weakness of the study is its cross-sectional design, which does not allow for the study of emerging behavior change. A prospective, longitudinal study of these phenomena will be the natural next step in this research program.

These limitations aside, we conclude that abnormal behavior is common in MS and a syndrome characterized by euphoria, lability, and disinhibition and can be reliably detected using the NPI. We estimate the frequency of

euphoria sclerotica to be 9%. The syndrome is associated with low agreeableness on personality measures, poor insight, cognitive impairment, and high levels of caregiver distress. Identification of this syndrome could impact favorably on the clinical care of MS patients via the development of new pharmacological treatments

31 and counseling strategies for improving patient/caregiver interactions.

32