Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is reported to account for up to 20% of all cases of dementia in old age.

1,2 Cognitive impairment in DLB is characterized by marked visuospatial difficulties and/or working memory problems (see Simard et al.

3 for a review), and an alteration of episodic memory significantly less severe than that found in Alzheimer's disease (AD).

4 Cognitive fluctuations are one of the three essential features required to meet the diagnostic criteria of DLB.

5 Perry et al.

6 suggested that the pathology of mesopontine cholinergic neurons might impair the level of conscious awareness and thus the sleeping and daytime activity cycle in DLB. Consequently, the administration of cholinergic agents should theoretically improve the level of consciousness and vigilance in subjects with DLB, and should also impact on their cognitive and behavioral functioning. Indeed, the results of a retrospective neuropathological study seems to support the view of an important role of acetylcholinergic depletion in the cognitive impairment found in DLB.

7 In that particular study, it was found that three subjects among those initially diagnosed with AD, and who had presented more significant improvement in cognition after receiving doses up to 150 mg/day of tacrine in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial,

8 were in fact presenting with Lewy bodies in the cingulate cortex, in addition to senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles typical of AD in the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes.

7 More recently, Tiraboschi et al.

9 have studied the timing of cholinergic deficits in 50 patients with DLB compared with 89 subjects with AD and 18 healthy control subjects. They found that seven subjects with mild DLB had significantly less ChAT activity in the superior temporal, inferior parietal and midfrontal cerebral areas than the control subjects, whereas 14 subjects with mild AD had ChAT activity comparable to that of control subjects. In addition, when less impaired patients (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] >10) underwent separate analysis, the correlations of ChAT activity with the MMSE score was strong and significant for the DLB group alone.

9Besides cognitive fluctuations and decline, hallucinations are also one of the three essential features required to meet the current criteria for DLB,

5 and they are reported to be the most distinctive behavioral characteristic of DLB, compared to AD, at onset or at any stage during the disease.

3 Spontaneous parkinsonism or extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) (not secondary to a neuroleptic sensitivity syndrome) are the last of the three possible and essential features of DLB. The treatment of psychotic symptoms in DLB is complicated by the frequent occurrence of a neuroleptic sensitivity syndrome, following the intake of common neuroleptics

1 and risperidone,

10,11which frequently triggers the onset or exacerbates the existing EPS. Other atypical neuroleptics such as clozapine and olanzapine have also been reported to cause adverse events such as increased confusion, hallucinations and paranoid delusions (clozapine; olanzapine) and marked EPS (olanzapine).

12–14The challenging treatment of psychosis in DLB using both typical and atypical neuroleptics necessarily prompts research into compounds that could improve the symptoms without threatening the life and well being of the patients. On the other hand, some evidence suggests a relation between the reduction and/or modulation of cholinergic activities and the presence of psychosis in DLB. The cortical cholinergic enzyme choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) activities were found to be significantly reduced by 80%–85% in the parietal (

P=0.009) and temporal (

P=0.015) cortex of six DLB subjects with visual hallucinations compared with 50%–55% in six nonhallucinating DLB subjects.

15 The total amount of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, especially the m

4 receptors, in the temporal cortex of seven subjects with DLB has been reported significantly lower compared to those of control subjects, whereas the m

1 receptors were higher, and the m

2 receptors lower than those of 11 subjects with AD.

16 More recently, Ballard et al.

17 demonstrated that delusions were associated with elevated pirenzepine binding (postsynaptic m

1 receptor autoradiography) in the fourth temporal gyrus of subjects with DLB, whereas visual hallucinations were associated with significant reductions in ChAT. These authors suggested that the up-regulation of the postsynaptic muscarinic receptors may be central in the genesis of delusions. Therefore, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor agents, by compensating for the lack of acetylcholine, may theoretically provide a treatment solution for psychosis and behavioral symptoms in dementia, and especially in DLB.

There is certainly a biological rationale for the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) in DLB. However, given the frailty of the individuals suffering from DLB, the clinical utilization, on a regular basis, of the AChEIs cannot be advised before critical appraisal of the existing evidence regarding the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of this type of medications has been performed.

Thus the goal of the present paper is to critically and exhaustively review the evidence reported in the literature regarding the efficacy, tolerability and safety of various AChEIs for treatment of DLB. Specifically, this review examines the efficacy of AChEIs in improving the behavioral, cognitive and functional symptoms, as well as the tolerability and safety of the various AChEIs utilized for treatment of DLB, especially in regards to the EPS. The ultimate goal of this paper is to provide a scientific rationale to future research studies aimed at treating the symptoms of DLB.

METHOD

PubMed-Medline (1965–July 2002) has been searched using the following key words: Lewy bodies and 1) tacrine; 2) donepezil; 3) ENA-713 or rivastigmine; 4) physostigmine; 5) galantamine; 6) metrifonate. Only published articles written in English were included in the review. The effects of medication were considered significant: 1) when one or several statistical analyses clearly demonstrated an improvement, a deterioration, or a difference between one or several groups of subjects; and 2) when, in the case reports without psychometric evaluations, the authors specified the type of change, and the extent of improvement or deterioration on particular symptoms.

RESULTS

Only articles on the use of tacrine, donepezil, and rivastigmine in DLB have been found. The subjects with DLB included in all the studies of the current review met the clinical diagnostic criteria of the Consortium on Dementia With Lewy Bodies,

5 and, when mentioned, the subjects with AD met the NINCDS-ADRDA diagnostic criteria.

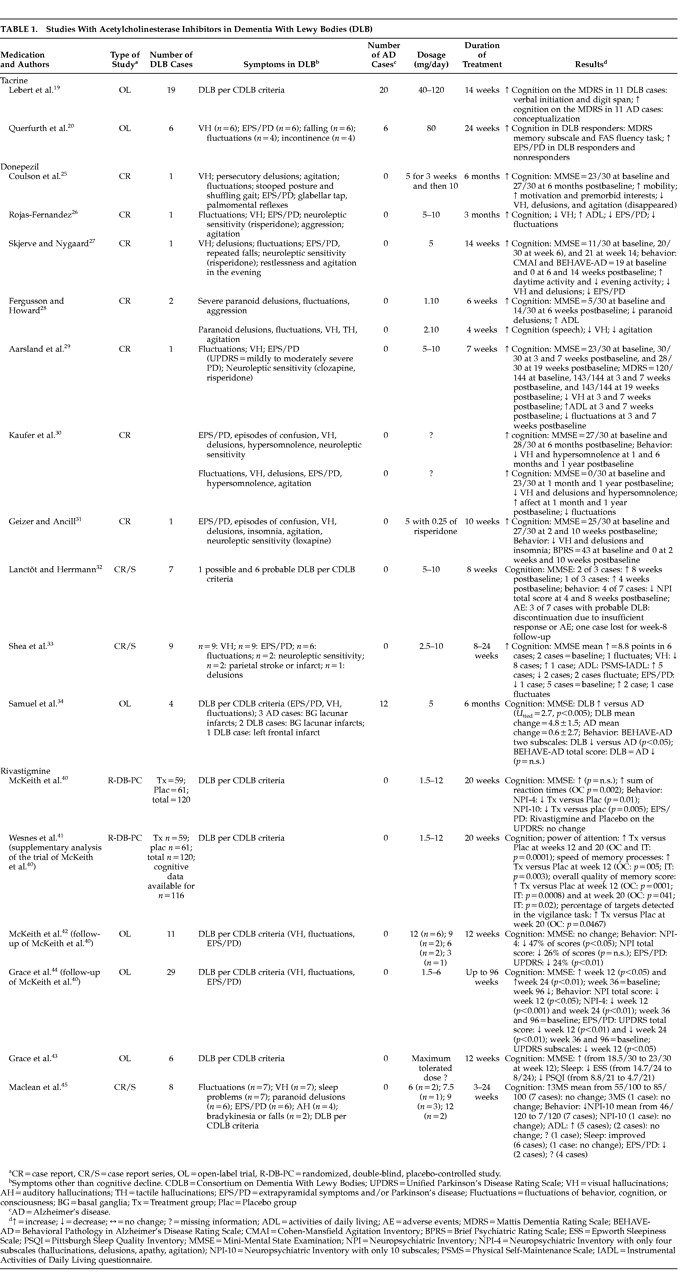

18 Table 1 shows the results of the case reports and trials for each compound, and

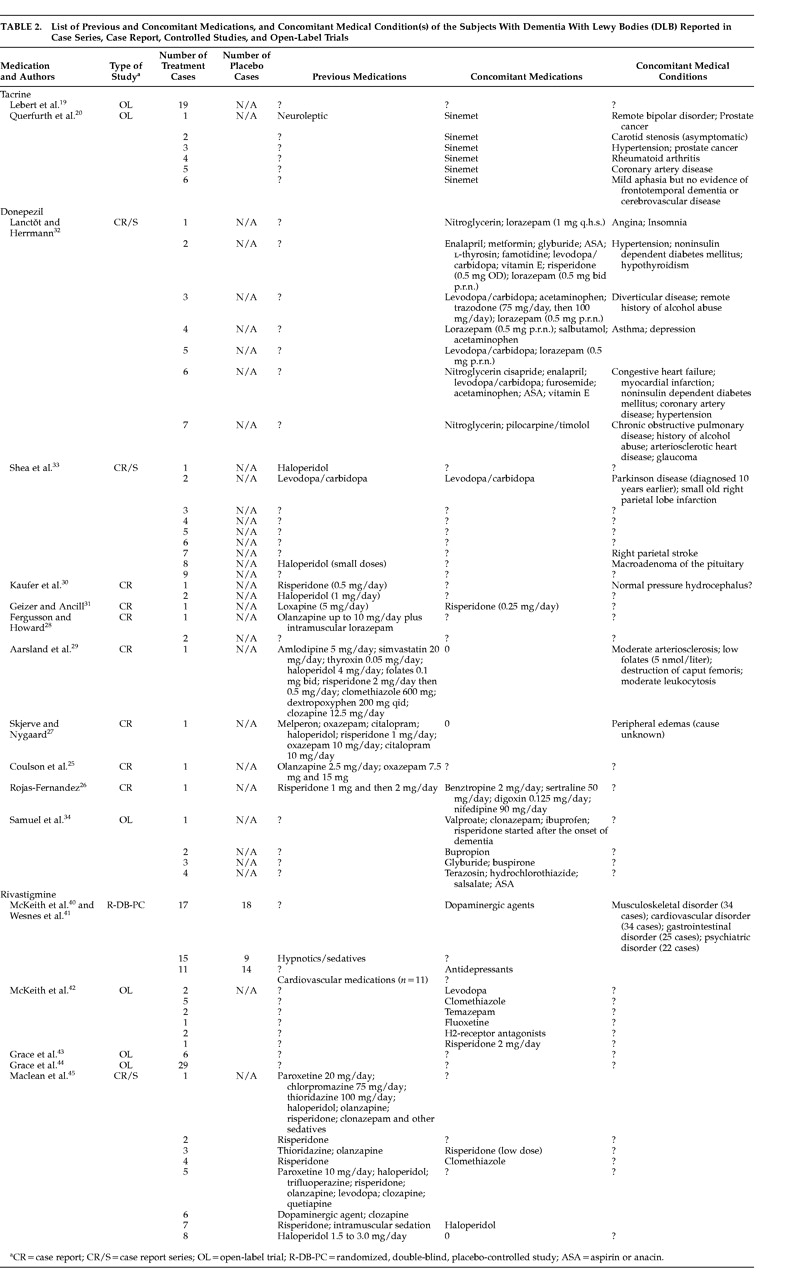

Table 2 shows the list of the previous and concomitant medications used by the subjects involved in the studies, as well as their concomitant medical condition(s).

The Evidence Regarding Tacrine

Two open-label studies with between diagnostic group comparisons reported the effects of 40 to 120 mg/day of tacrine on cognition,

19,20 and EPS

20 in DLB and AD.

Characteristics of the Subjects Involved in the Tacrine Studies

In both studies, the DLB subjects were mildly to moderately demented at baseline (MMSE

21 scores between 10 and 24), and were compared with mildly to moderately demented subjects with probable AD.

Previous and Concomitant Medications, and Concomitant Medical Conditions

Lebert et al.

19 did not mention the previous and concomitant medications, as well as the concomitant medical conditions of the subjects involved in their study. Only the study of Querfurth et al.

20 provided information regarding previous and concomitant medications as well as concomitant medical conditions; all six subjects were taking a dopaminergic agent (Sinemet) during the trial. One of these subjects previously had taken a neuroleptic and the name of that agent was not specified by the authors. Three of the subjects had a cardiac or hypertensive condition; one subject had a history of bipolar disorder and another one had prostate cancer.

20Cognitive and Safety Measures Used in the Tacrine Studies

Cognition was tested with the MMSE for the determination of dementia severity at baseline in both studies. The effects of the tacrine treatment were assessed using the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale

22 (MDRS) in the two studies.

19,20 Lebert et al.

19 also utilized a global evaluation, the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale, whereas Querfurth et al.

20 administered the Controlled Word Association Test (FAS Verbal Fluency TFask), the Trail Making Test, the Boston Naming Test, Visual Reproduction and Logical Memory tests from the Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised, Clock Drawing, and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Only Querfurth used standardized assessments of EPS, namely the Hoehn and Yahr staging system

23 and the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale

24 (UPDRS).

Results of the Tacrine Studies

Lebert et al.

19 compared the cognitive functioning of 19 subjects with DLB and 20 subjects with AD. The titration schedule was 40 mg/day for 6 weeks; 80 mg/day for 6 weeks; and 120 mg/day for 2 weeks (total treatment duration=14 weeks). Patients were assessed at baseline and at week 14 with the MDRS and the CGI scale. More than half of the patients responded to the treatment in both subject groups: 11 of 19 subjects with DLB, and 11 of 20 subjects with AD. The MDRS scores at week 14 significantly differed (

U=–3.62,

p=0.0003) between the responders (mean MDRS score=114.04±16.25) and the nonresponders (mean MDRS score=81.57±24.65). The 11 subjects with DLB significantly improved on the Digit Span (

t=–1.96,

p=0.005), and the Verbal Initiation (

t=–1.95,

p=0.05) tasks of the MDRS, whereas the 11 subjects with AD improved on the Conceptualization subtest of the MDRS (

t=–2.85,

p=0.004). Regarding safety and tolerability, eight (20.5%) of 39 patients had side effects, six (15.4%) developed a comorbid condition, and 14 (35.9%) did not comply with medication or were treated with drugs contraindicated with tacrine.

Querfurth et al.

20 compared the cognitive functioning of six subjects with DLB and six subjects with AD. Subjects with DLB experiencing fluctuations in alertness at the baseline assessment were excluded from the study. All the subjects with DLB had moderately severe parkinsonism (mean Hoehn and Yahr stage=3.8±0.6), received Sinemet at baseline, and continued to receive this medication throughout the 24-week trial. The DLB and AD patients first received 40 mg/day for 6 weeks, then the dose was titrated to 80 mg/day, which was maintained up until the 24-week cognitive follow-up endpoint. Querfurth et al.

20 divided the DLB group between the responders (DLBr;

n=3; baseline MMSE scores >15), and the nonresponders (DLBnr;

n=3; baseline MMSE score ≤14). At baseline, the DLBr and AD groups had comparable performances on the total score of the MDRS, the Conceptualization Subscale and the FAS Verbal Fluency Task. However, the performance of the DLBr subjects was significantly superior to those of the DLBnr and AD groups on the Memory subscale of the MDRS (

p<0.01); this performance remained significantly superior to those of the other two groups until week 24 (DLBr versus AD,

p<0.0002; DLBnr versus DLBr and AD,

p<0.002). Among the three groups of subjects, the DLBr was the only group to show some improvement on the MDRS total score, the Memory and Conceptualization Subscale of the MDRS, and the FAS fluency task; however, the only significant improvement at week 24 compared to baseline occurred on the FAS fluency task (

p<0.015). There was no change or significant improvement on the other cognitive tests and on the Geriatric Depression Scale. The DLBnr registered the worst performances at baseline and at week 24 on all the tests, including the MMSE, suggesting that they were more severely demented than the responders at the start of the trial. Regarding safety, parkinsonism worsened from baseline to week 24 in all subjects with DLB with a mean increase on the Hoehn and Yahr stage of 0.8±0.3 points, and of 1.7±1.0 points on the UPDRS.

The Evidence Regarding Donepezil

Ten studies including seven case reports,

25–31 two case series,

32,33 and one open-label study with between diagnostic group comparisons

34 described the effects of 5 to 10 mg/day of donepezil in 29 subjects with DLB (

Table 1). Only one study

34 compared the efficacy of 5 mg/day of donepezil in four subjects with DLB, and 12 subjects with AD. The duration of the 10 studies varied from 4 weeks to 1 year.

Characteristics of the Subjects Involved in the Donepezil Studies

According to the MMSE scores at baseline, 12 subjects with DLB had mild (MMSE scores from 20.5 to 30),

25,28–31,33,34 11 had moderate (MMSE scores from 11 to 19),

27,32,33 and five had severe dementia (MMSE scores from 0 to 5).

28,30,33 One case report

26 did not mention any MMSE or other test scores. In the case reports, the subjects were aged from 71 to 90 years, whereas in the case series, the mean ages were 76.8±5.7 (range=67 to 84),

33 and 75.3±4.7 years (range=68 to 81).

32 In the open-label trial with diagnostic group comparisons,

34 the mean ages of subjects with DLB and AD were comparable (DLB=79.8±5.6 years, and AD=76.0±13.1 years).

Previous and Concomitant Medications and Concomitant Medical Conditions

In eight studies,

25–31,33 typical and atypical neuroleptics, antidepressant (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), benzodiazepine, levodopa/carbidopa, anticonvulsant, cardiac, and thyroid agents were administered prior to the trials of donepezil. No washout period or any indication of the time interval between the previous medications and the starting of donepezil were reported in six

25,26,28,30,31,33 of the eight studies. Information regarding the previous medications was missing in two studies.

32,34Two studies specified that their subjects did not receive any concomitant medications following 5-week

29 and 7-day

27 washout periods; whereas the use of benzodiazepines, levodopa/carbidopa, atypical neuroleptic (risperidone), various antidepressants, anticonvulsant and cardiac medications along with diuretic, hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic compounds were described in five studies.

26,31–34 Of interest, one case report

26 mentioned the concomitant use of an anticholinergic (benztropine) in one patient. Information regarding concomitant medications was missing in three studies.

25,28,30Five studies described concomitant medical conditions such as cerebrovascular infarction or stroke

33 (two cases), cardiac (three cases) and pulmonary diseases

29,32 (two cases), hypertension (one case), diabetes (two cases), hypothyroidism

32 (one case), macroadenoma of the pituitary

33 (one case), history of alcohol abuse

32 (two cases) and various peripheral medical problems

27,29,32 (three cases). Five studies

25,26,28–31,34 did not mention any concomitant medical conditions in the subjects.

Cognition

Cognition has principally been assessed with the MMSE

21 in nine

25,27–34 of the 10 papers. Twenty-two of the 29 subjects who had received donepezil improved their cognitive functioning 4 weeks to 1 year postbaseline whereas seven subjects did not register any improvement in cognition.

25–34 The baseline and posttreatment MMSE scores were available in 19 of the 22 “improved” cases described in eight different anecdotal reports,

25,27–33 and one open-label study,

34 and revealed positive changes from 1 to 23 points (see

Table 1 for more details). Three other cases

26,28,33 without any MMSE or other psychometric assessment were reported to clinically improve, either by a clinician or a caregiver (one case).

Behavior

The utilization of standardized questionnaires or scales to measure the behavioral and psychotic symptoms has been mentioned in only four

27,31,32,34 of 10 papers. Skjerve and Nygaard

27 as well as Samuel et al.

34 used the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale

35 (BEHAVE-AD); Skjerve and Nygaard

26 also utilized the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory

36 (CMAI); Lanctôt and Herrmann

32 used the Neuropsychiatric Inventory

37 (NPI); and Geizer and Ancill

31 used the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

38 (BPRS). The six other articles

25,26,28–30,33 relied on the observations of the physicians and/or the caregivers to assess the presence and severity of the behavioral and psychotic symptoms. Twenty-five of the 29 patients reported in the 10 articles registered a decrease in the psychotic and/or behavioral symptoms.

25–34 Twenty subjects among the 25 improved cases had a significant decrease in visual hallucinations with 5 to 10 mg/day of donepezil, 4 weeks to 1 year following baseline.

25–33 Skjerve and Nygaard

27 found a significant decrease in the activity disturbances (agitation), hallucinations, anxiety, and aggressiveness, as measured by the BEHAVE-AD and the CMAI, in one subject with moderate dementia. In the open-label trial of Samuel et al.,

34 the psychotic and behavioral symptoms measured by the two subscales “Paranoid and delusional ideation” and “Affective disturbance” of the BEHAVE-AD significantly declined in the four subjects with DLB (mild dementia) compared with the 12 subjects with AD, after 6 months of receiving 5 mg/day of donepezil; however, on the total score of the BEHAVE-AD, the two patient groups did not significantly differ.

Functional Assessment

Function has not been psychometrically assessed by most of the studies using donepezil included in the present review; the authors instead relied on their clinical observations and/or the reports of the caregivers. Only Shea et al.

33 utilized specific instruments to measure function, namely the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale,

39 and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living questionnaire (IADL). Improvements in the activities of daily living were especially mentioned in eight cases with DLB reported in four different papers.

26,28,29,33Safety

Regarding safety issues, the EPS were not systematically quantified at baseline and postbaseline in most of the donepezil studies included in the present review. Therefore, the reported EPS were the results of the physicians' observations. Among the 25 subjects with DLB identified by the authors of nine articles as presenting EPS at baseline,

25–27,29–34 three patients significantly improved 3 months,

26 14 weeks,

27 and 24 weeks

33 postbaseline. Shea et al.

33 specifically reported that EPS worsened in two subjects, and fluctuated in another subject. The effects of donepezil on the EPS of the other subjects were not reported.

26,27,29–32,34Four subjects with DLB (moderate dementia) did not respond well or experienced adverse events.

32,33 One subject receiving 5 mg/day discontinued the treatment 4 weeks postbaseline because of insufficient response; two patients receiving 5 mg/day discontinued the treatment respectively after 1 and 6 weeks because of serious adverse events such as, in the first case, somnolence and exacerbation of previously stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and in the second case, syncope, bradycardia, and sweating.

32 Finally, one patient receiving 5 mg/day had a worsening of his psychotic symptoms, and then short-lived episodes of improvement after an increase of the dose to 10 mg/day.

33The Evidence Regarding Rivastigmine

Six studies, including two randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials,

40,41 three open-label studies,

42–44 and one case series

45 were found. The articles of McKeith et al.

40 and Wesnes et al.

41 report data of the same trial; whereas the open label trials of McKeith et al.

42 and Grace et al.

43,44 are the follow-up studies of the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of McKeith et al.

40 Only the case series of Maclean et al.

45 is unrelated to the trial of McKeith et al.

40Characteristics of the Subjects Involved in the Rivastigmine Studies

The subjects included in all the studies had mild to moderate dementia, and were aged between a mean of 74.25 and 78.5 years in the open label trials

42–44 and the case series.

45 The treatment and placebo groups were aged, respectively, 73.9±6.5 and 73.9±6.4 years in the studies of McKeith et al.

40 and Wesnes et al.

41Previous and Concomitant Medications and Concomitant Medical Conditions

Dopaminergic agents and antidepressants have been used concomitantly to rivastigmine in the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial whereas the hypnotics/sedatives and cardiovascular medications have been discontinued after baseline.

40,41 The subjects involved in this study were suffering from musculoskeletal, cardiac, gastrointestinal and psychiatric disorders.

40,41 Of the follow-up open label trials, only that of McKeith et al.

42 reported the concomitant use of medications, namely, dopaminergic agent, antidepressant, atypical neuroleptic, sedative/anticonvulsant, benzodiazepine and H2-receptor antagonist. In the eight-case series of Maclean et al.,

45 various atypical (six cases) and typical (four cases) neuroleptics, antidepressants (two cases), benzodiazepines (two cases), and dopaminergic agent (one case) have been administered prior to the trial of rivastigmine; whereas risperidone (one case), clozapine (one case), haloperidol (one case), clomethiazole (one case) and a dopaminergic agent (one case) were reported to have been used concomitantly with rivastigmine.

45 No washout period or any indication of the time interval between the previous medications (other than rivastigmine) and the starting of rivastigmine have been reported in four of six rivastigmine studies.

42–45 No concomitant medical conditions were listed for the open label trials

42–44 and the case series.

45Cognitive, Behavioral, and Safety Measures Used in the Studies

In order to measure the changes in cognition, four studies

40,42–44 utilized the MMSE, two studies

40,41 utilized the Cognitive Drug Research (CDR) computerized assessment system, and one study

45 utilized a modified and lengthier version of the MMSE, the Modified MMSE, also called the 3MS,

46 with a maximum possible score of 100. The CDR computerized assessment system consists of tests of attention, working memory, and episodic memory, which have previously been validated in trials of AChEIs in AD.

47,48Regarding the assessment of change in behavioral symptoms, three studies

40,42,44 used the NPI-4, which involves only four subscales of the original NPI (delusions, apathy, agitation, and hallucinations); two studies

40,45 used the NPI-10, involving 10 of the 12 original subscales, which is the NPI version used in the nursing home; one study

42 used the NPI; and one study

43 utilized the Epworth Sleepiness Scale

49 (ESS) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory

50 (PSQI) to measure changes in the sleep pattern.

Regarding the assessment of safety, three studies

40,42,44 measured changes in EPS using the UPDRS

23 together with a discontinuation rate. The remaining three studies

41,43,45 did not report the use of a quantifying method to record adverse events.

Results of the Rivastigmine Studies

The randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study included 120 subjects with Dementia with Lewy bodies assigned to the treatment (

n=59) or the placebo group (

n=61) for 20 weeks;

40 the treatment phase was followed by a discontinuation period of 3 weeks. The maximum daily dose (12 mg) was reached by 27 of the 48 patients, whereas the 6–12 mg/day doses were reached by 44 of the 48 patients. In the particular paper of McKeith et al.,

40 the results represented the sum of latencies measured from the CDR computerized assessment tests calculated as the unweighted sum of simple, choice, digit vigilance, numeric working memory, spatial memory, word recognition, and picture recognition reaction times. These results were given as change values in milliseconds, and were provided in three sets of data: intent to treat (ITT), last observation carried forward (LOCF), and observed cases (OC). A significant improvement in cognition occurred in the rivastigmine group, as measured by the computerized cognitive assessment system, in all three data sets at week 12 (ITT

p=0.10; LOCF

p=0.005; OC

p=0.002) and at week 20 (ITT

p=0.048; LOCF

p=0.046; OC

p=0.017), with the following mean change values from baseline: 1084 and 1318 ms at weeks 12 and 20, respectively), compared with the placebo group (mean change values: –2503 and –991 ms). The mean changes on the MMSE and the Clinical Global Change-plus were not significant. Regarding the behavioral symptoms, the rivastigmine group had a significant improvement, compared with the placebo group, as measured by the NPI-4 (mean change of 4.1±8.3 in the treated group compared with 0.7±7.4 in the placebo group; OC

p=0.010); and the NPI-10 (mean change of 7.3±13.7 in the rivastigmine group compared with 0.9±10.4 in the placebo group; OC

p=0.005). Regarding safety issues, the rivastigmine group had a higher discontinuation rate of 30.5% (

n=18) compared with 16.4% (

n=10) in the placebo group. More subjects on rivastigmine (54.92%) than placebo (46.75%) experienced adverse events, principally cholinergic in nature: nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and somnolence. There was no change in the EPS of the rivastigmine and placebo groups, as measured by the UPDRS; however an emergent tremor was registered as an adverse event in four patients treated with rivastigmine.

40The study of Wesnes et al.

41 provided further analyses on the cognitive functioning of the patients involved in the trial of McKeith et al.,

40 and using specific factors of the CDR computerized assessment system. In that particular study, the cognitive data were available for 116 of the initial 120 patients with DLB who entered McKeith's randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

40 The group receiving rivastigmine improved compared with the placebo group on the following factors: power of attention at weeks 12 and 20 (OC and ITT

p=0.0001); speed of memory processes at week 12 (OC

p=005; ITT

p=0.003); overall quality of memory score at week 12 (OC

p=0001; ITT

p=0.0008) and week 20 (OC

p=041; ITT

p=0.02). In addition the percentage of targets detected in the vigilance task significantly increased in the rivastigmine group at week 20 (OC

p=0.0467) compared with the placebo group.

41The open-label trial of McKeith et al.

42 was started after a 3-week washout period following the treatment period of the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study.

40 Eight men and three women completed 12 weeks of treatment with a mean daily dose of 9.6±3.2 mg of rivastigmine at endpoint. At baseline, the patients had EPS (mean UPDRS score=24.5±14.1), behavioral problems (mean NPI-4=13.6±7.1; mean NPI=28.7±14.4), and were all taking concomitant medications. At the end of the trial, the behavioral symptoms, as measured by the NPI-4 (decrease of 47%) had significantly improved. Reductions in mean scores on each of the NPI-4 items were as follows: delusions 73%, apathy 63%, agitation 45%, and hallucinations 27%. There was no significant change in cognition (3.9% of increase on the MMSE;

P=n.s.), and on the NPI. The authors did not mention the proportion of the 11 subjects who received and those who did not receive rivastigmine in the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Thus some of these subjects might have been exposed to rivastigmine for the first time in the open label trial as opposed to other subjects who may have received rivastigmine previously, in the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. These latter subjects may have benefited of a longer exposure to the compound. Therefore, one does not know if the results of this open label trial reflect a new or a continued response to the drug. Regarding safety, the EPS had significantly decreased (24% on the UPDRS). Nausea and diarrhea were the most common reported side effects; no severe adverse events occurred.

The 12-week open-label trial of Grace et al.

43 particularly studied the effect of rivastigmine at maximum tolerated dose on the sleeping profile of six subjects with DLB, as measured by the ESS,

49 and the PSQI.

50 At baseline, the subjects with DLB had the tendency to fall asleep at inappropriate times during the day. The sleeping patterns of the patients with DLB improved on the PSQI (from a mean of 8.8/21 at baseline to 4.7/21 at week 12) and on the ESS (from a mean at baseline of 14.7/24 to 8.0/24 at week 12). Cognition also improved, as assessed by the MMSE, from a mean of 18.5/30 at baseline to 23/30 at week 12. Unfortunately, no variance analyses were performed due to the small sample size.

The study of Grace et al.

44 is the continuation of the previous open-label trials of McKeith et al.,

42,43 and included 29 subjects with DLB. Cognition (as measured by the MMSE), the behavioral disturbances (as measured by the NPI-4), and the EPS (as measured by the UPDRS) significantly improved 12 and 24 weeks postbaseline, with 3 to 12 mg/day of rivastigmine. The scores on the NPI-4 and the UPDRS went back to those of baseline at weeks 36 and 96, whereas the scores on the MMSE went back to those of baseline at week 36, and declined below baseline scores at weeks 84 and 96. There was a high discontinuation rate of 31.0% (nine of 29 subjects): four subjects discontinued after 24 weeks of treatment because of side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and “flu-like symptoms”; one had electrocardiographic changes suggesting a serious cardiac arrhythmia following a myocardial infarction; and four subjects were nonresponders after 30.5 weeks of treatment. One patient died of unrelated causes while on medication.

In the case series of Maclean et al.

45 involving a total of eight subjects, two subjects received 6 mg/day, one subject received 7.5 mg/day, three subjects received 9 mg/day, and two subjects received 12 mg/day of rivastigmine. Three to 24 weeks postbaseline, cognition and behavior had improved in seven subjects (their scores on the 3MS increased from a mean of 55/100 to a mean of 85/100; and their scores on the NPI-10 decreased from a mean of 46/120 to a mean of 7/120). Six cases reported a better sleep; five cases reported some improvement in activities of daily living and two cases reported an improvement in EPS. However, the changes in sleep pattern, activities of daily living and EPS were not formally assessed with psychometric instruments. Only one subject registered a lack of change in cognition and behavior after a month of receiving 9 mg/day and was thus discontinued because of the lack of efficacy.

45DISCUSSION

Cognitive Efficacy

Mildly to moderately demented DLB subjects receiving rivastigmine with doses of 3 to 12 mg/day, and subjects responding to tacrine with doses of 80 to 120 mg/day, have shown significant improvement in cognition on tests sensitive to vigilance (cognitive speed score), verbal and spatial working memory, episodic memory, attention, verbal initiation and executive function. However, this cognitive improvement was less impressive on the MMSE total scores. Rivastigmine has shown improvement in cognition with the MMSE only in two of three follow-up open-label trials of the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial with mildly demented subjects;

43,44 and the cognitive improvement in the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial has only been evidenced on the cognitive speed score.

40 There is a potential problem with the utilization of a cognitive speed score to assess change in cognition. The cognitive speed score, as described by McKeith et al.,

40 is either a measure of execution time or a measure of time reaction on tasks of working and episodic memory, attention, and executive functions, all involving some psychomotor abilities. Although that was not the case in the study of McKeith et al.,

40 open label trials with rivastigmine have shown an improvement in the EPS of subjects with DLB; the use of a “cognitive speed score” might therefore assess a change in motor functions instead of a change in cognition. The utilization of scores representing the actual number of successful items on tasks of attention, memory and executive functions might be more appropriate to distinguish between a cognitive and a motor improvement.

The improvement on cognition following the administration of 5 to 10 mg/day of donepezil has been less consistent and less clinically significant than the improvement described in behavioral symptoms. This might be due to the poor assessment of cognition with the sole use of the MMSE in eight of 10 donepezil studies, and/or to the small number of subjects involved in those studies. The MMSE has previously been criticized to lack sensitivity in measuring cognitive change following nootropic treatment in AD.

52 It also lacks sensitivity to measure the cognitive deficits characterizing DLB such as problems of vigilance, working memory, attention, executive functions, and episodic memory with free and cued recall paradigm.

3,4Behavioral Efficacy

Donepezil and rivastigmine have demonstrated some efficacy in improving the behavioral symptoms in subjects with DLB. The ameliorations were found in subjects with mild to moderate dementia. Doses of 5 to 10 mg/day of donepezil, and doses of 3 to 12 mg/day of rivastigmine particularly improved hallucinations, especially visual hallucinations, paranoid delusions and level of nighttime and daytime activity (hypersomnolence during the day; sleeping profile at night; apathy; aggressiveness; agitation). The majority of the patients tolerated doses between 6 and 12 mg/day of rivastigmine in the four studies that systematically measured the behavioral symptoms using psychometric instruments. In these studies, the NPI-4 appeared to be more sensitive to change than the long versions of this instrument (NPI and NPI-10).

A majority of the studies with donepezil relied on clinical judgment and observations instead of quantified scores to evaluate change in behavioral symptoms; a minority of the studies utilized the BEHAVE-AD, the NPI, the BPRS and the CMAI. As with the NPI in studies with rivastigmine, only particular subscales of the BEHAVE-AD used in the study with donepezil demonstrated significant change over time in subjects with mild dementia: the “Paranoid and delusional ideation” and “Affective disturbance” subscales. Unfortunately, behavioral symptoms were not assessed in the two studies with tacrine reported in the present review.

Activities of daily living have been reported to significantly improve in eight cases treated with donepezil,

26,28,29,33 and in a series of five cases treated with rivastigmine,

45 probably as a consequence of the improvement in behavioral and cognitive symptoms. Unfortunately, the authors reporting the results on the other trials of donepezil and rivastigmine, as well as the authors reporting the data on the tacrine trials, did not measure or comment on the change in the activities of daily living of the subjects with DLB.

Review of Safety

The procholinergic effect of the AChEIs might theoretically cause a worsening of EPS in the treated patients. However, such a worsening was only reported in one study using tacrine, and in two cases receiving donepezil, but was only observed anecdotally in four subjects of the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial with rivastigmine. In fact, in many cases, rivastigmine has improved EPS in subjects with DLB as demonstrated by significant improvements on the UPDRS obtained in two open label trials

42,44 and one case series.

45 Comparatively, when treated with donepezil, three subjects from three different studies were reported to have a significant decrease in their EPS up to 6 months postbaseline. The reason for this improvement is not clear; however, modulation activities between the cortical inhibition of AChEI and levels of cortical catecholamines and between the dopaminergic and ACh-nicotinic striatal receptors reported in the literature might be responsible. Donepezil has been shown to increase levels of catecholamines, including dopamine, in the cortex of rats.

54 The activation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the dorsal striatum has been demonstrated to contribute to dopamine and activity-dependent changes in synaptic efficacy.

55 These AChEI and ACh activities might affect the dopamine levels and possibly improve EPS.

Almost half of the subjects with DLB receiving tacrine did not respond to the compound. Similar rate

56–58 and pattern

59 of response to tacrine have previously been described in AD trials; therefore the lack of response to tacrine is unlikely caused by a specific incompatibility with the Lewy body pathology. Comparably, four of the 25 reported cases receiving donepezil did not respond and/or presented with adverse events.

32,33 The subjects receiving donepezil who discontinued because of adverse reactions or insufficient response, and the tacrine nonresponders were more in the moderate than mild stage of dementia, compared with the good responders. In addition, some subjects receiving donepezil who had to discontinue early in the trial presented medical conditions at baseline that are usually relatively contraindicated to the prescription of AChEIs: an obstructive pulmonary disease and a cardiac condition. These data suggest that tacrine and donepezil might be safer for subjects with DLB in the mild stage than in the moderate to severe stages of dementia, and in subjects not presenting certain cardiac and pulmonary conditions.

The discontinuation rates in the two rivastigmine studies involving the largest samples of the present review were, respectively, 30.5%

40 and 31.0%,

44 but 0% in two open-label trials. These dropout rates are comparable to those described in rivastigmine trials with AD.

60 The side effects were the usual gastrointestinal cholinergic effects, with no serious consequences. The randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of rivastigmine clearly identified a number of concomitant and previous medications as well as a number of concomitant medical conditions in the subjects involved in the study; the absence of severe adverse events found in this particular study suggests that rivastigmine might potentially be administered to more severely demented subjects with DLB. However, before such a trial shall be undertaken, the McKeith et al.

40 data need to be replicated in other phase III clinical trials.

Limitations of the Reviewed Studies

The quality of evidence was poor especially for donepezil and tacrine. Of a total of 18 studies included in the present review, only two were randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials, and the data of these two trials are derived from the same sample of subjects tested with rivastigmine. The majority of the studies were cases reports or case series (10 of the 18 studies), and the remaining studies were open label trials (three studies) or open label trials with a comparison sample (AD) (three studies).

The size of the samples was also limited: from one to nine subjects in case reports and case series, from four to 19 subjects in controlled studies, and from six to 29 subjects in open label trials. The largest sample involved 59 and 61 patients in the treatment and placebo groups respectively (the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials). The effect of small sample sizes is to potentially limit statistical power; the positive and negative effects of the compounds are thus more difficult to be objectively assessed.

Another problem with the papers included in this review was the lack of psychometric measurements for behavioral symptoms, activities of daily living, and EPS, as well as the lack of sensitive measurements of cognitive function, especially in the studies on donepezil. The MMSE that was generally utilized in those trials can hardly be considered a sensitive and thorough assessment of those cognitive functions which are usually impaired in the early stages of DLB.

51 However, despite the flaws of the current literature, some preliminary observations and conclusions can still be made, though the reader must keep in mind the limitations that have been underlined.

Suggestions for Future Research

Dementia with Lewy bodies is a severe syndrome involving symptoms that impact on the cognitive, behavioral and motor condition of the patients. Because the treatment of these symptoms is extremely challenging, clinicians and investigators working with DLB should consider keeping a log on previous and concomitant medications, as well as on all the concomitant medical conditions of the patients. The present review (

Table 2) has clearly shown that such a log is rarely complete in the studies reporting data on the use of AChEI in DLB. In many cases, the previous and/or concomitant medications were not reported, and when the previous medications were indeed reported, most of the time no washout period was mentioned between the intake of one psychotropic agent and the intake of the AChEI. An appropriate washout period is crucial both for research and clinical care. For example, many psychotropic drugs have fairly long half-lives, presenting the problem of drug interactions. As well, determining the cause of observed changes is complicated by too short a washout period, as the initial drug may have induced changes in the brain function (e.g., changes in receptor densities), which may persist well beyond the half-life of the drug. Hence are observed changes with the new drug related to the new drug or to the gradual loss of effect from the first drug? Conversely, combinations of two psychotropic compounds might be surprisingly beneficial: in the present review, 10 papers have described successful combinations of various psychotropic agents such as antiparkinsonian agents, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, low dose of risperidone and one of the AChEIs.

In addition to the positive interactive or antagonizing effects of some psychotropic agents, one should also pay attention to the impact of the AChEI on cardiac function: several subjects with DLB have a cardiac condition and take cardiac medication (

Table 2), and some subjects with DLB may even present with cerebrovascular lesions

61–63 (

Table 2, and the study of Shea et al.

33). The present review, though lacking of data in many instances, has evidenced that such a condition can negatively affect the outcome of an AChEI trial (

Table 2 and the results of Lancôt and Herrmann

32).

To date, there are no studies on the interaction effects of several medications in DLB, and on the efficacy and safety of switching protocols between two AChEIs. These are important questions that will have to be addressed in the near future, since the mildly demented patients who currently respond well to one agent, might need to switch to another AChEI as the dementia progresses.

None of the studies included in the current review commented on the effects of tacrine, donepezil or rivastigmine on the cognitive fluctuations, even though these symptoms were mentioned in a large number of subjects across the three drugs data set (see

Table 1). This situation might partly be attributed to the fact that there is no clear definition of “cognitive or confusion fluctuations” in terms of the intensity, duration and frequency of the episodes according to the criteria of the Consortium on Dementia With Lewy Bodies,

5 and also because until very recently, there was no instrument available to measure the cognitive or confusion fluctuations. This situation could be avoided in the future since at least two scales now exist that can address these symptoms: The Clinical Assessment of Fluctuation and the One Day Fluctuation Assessment Scale.

53In addition to a measure of cognitive fluctuations, the utilization of standardized psychometric instruments to assess changes in cognitive and behavioral functions, and also in activities of daily living should be systematic in future research. Cognitive tests should particularly evaluate problems of vigilance, working memory, attention, executive functions, and episodic memory with free and cued recall paradigms. The NPI-4 and some measure of the sleeping cycle would be indicated to assess behavioral changes.

Finally, because DLB could be viewed in clinical practice as being a “continuum diagnostic entity” between AD and Parkinson's disease, randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials should be designed to compare the relative efficacy and safety of the various AChEI in subjects meeting the clinical diagnostic criteria of the above mentioned diseases.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite methodological limitations, preliminary evidence with case reports, case series, open label trials and one randomized placebo-controlled study showed some efficacy in improving behavioral symptoms and cognition using AChEI such as donepezil and rivastigmine in patients with DLB. However, more randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials are badly needed before the use of any AChEI can be recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In 2002-2003, Dr. Simard and Dr. van Reekum conducted research funded by the Investigator Initiated Studies Program of the Zyprexa Research Fund/Eli Lilly Canada. Dr. Simard was involved in research sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. van Reekum is supported by the Kunin-Lunenfeld Applied Research Unit, Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care, Toronto, Canada.