In 1988, I and my colleague Michel Poncet

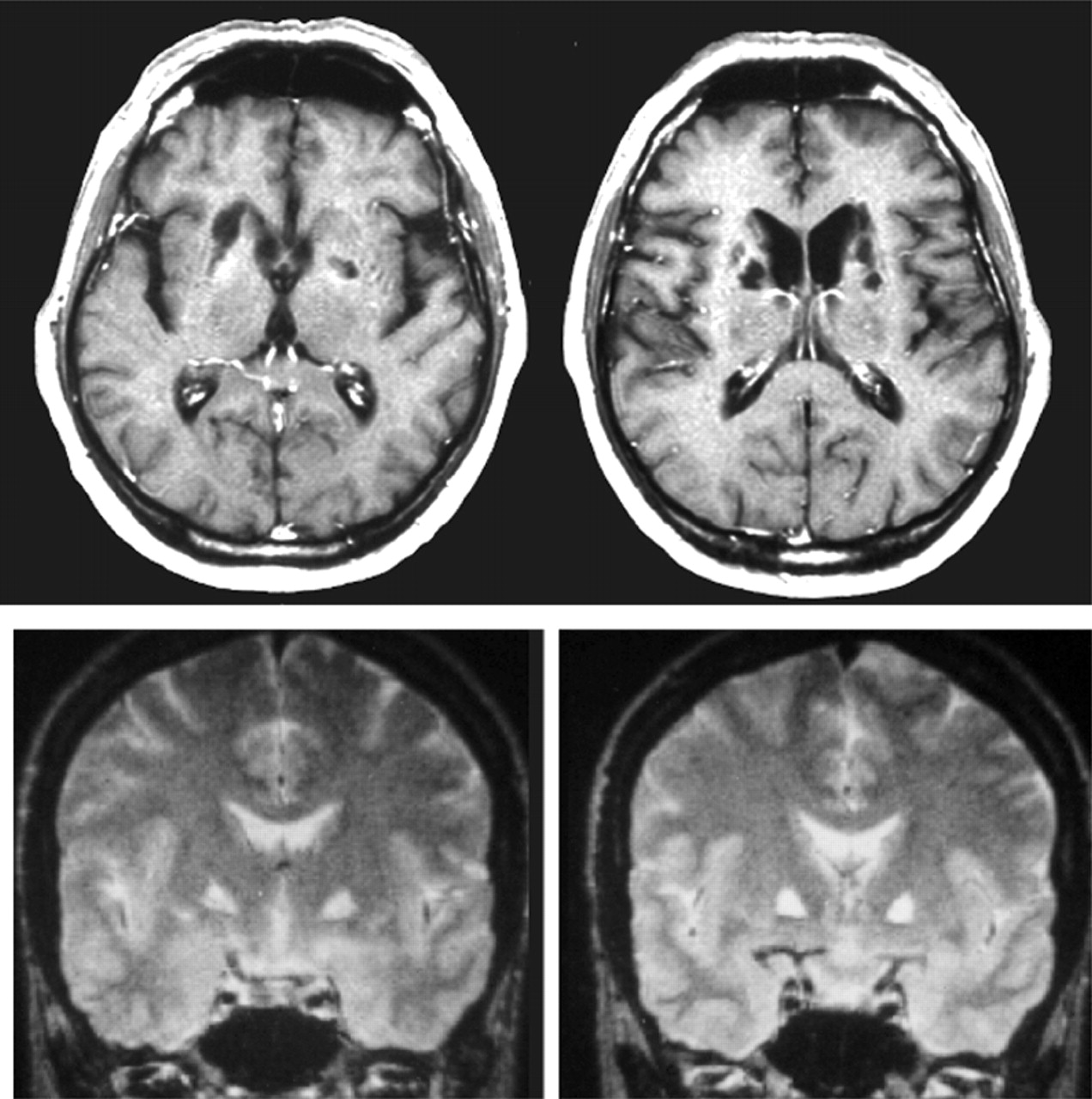

17 were struck by the similarity between these classical, almost forgotten, psychiatric notions, and the behavior of two patients we had examined with very comparable ischemic microlesions involving almost “surgically” the head of the caudate nucleus on both sides of the brain, as shown on MRI scans. Since that time, we and others have encountered and reported a number of similar cases, but it seems of interest, here, to briefly describe the clinical history of the two original cases which first attracted our attention.

Athymhormia in Striatal Lesions

First case.

This 64-year-old retired police officer was admitted to the neurology ward for “recent and abrupt behavioral change.” Over the 2 or 3 weeks prior to admission, he had become, according to his spouse, totally apathetic, inactive and prostrate. His medical history was unremarkable except for occasional bouts of elevated blood pressure, which had never justified continuous antihypertensive medication and rare episodes of angina pectoris. On admission, he was clearly hypokinetic with decreased spontaneous movements, facial amimia and Parkinson-like gait. Neurological examination was otherwise normal, except for a moderate limb stiffness. EEG showed mild nonspecific diffuse slowing and CT scan was interpreted as normal for the patient’s age. His general behavior was characterized by a dramatic decrease in spontaneous activity. Totally abulic, he made no plans, showed no evidence of needs, will, or desires. He showed obvious lack of concern about relatives’ as well as his own condition. When questioned about his mood, he reported no sadness or anxiety. Also noteworthy were a loss of appetite (he never asked for food, even if left more than 24 hours without eating) and food preferences (he would eat with the same apparent satisfaction dishes he did or did not like before). Finally, on every instance he was questioned about the content of his mind, he reported a striking absence of thoughts or spontaneous mental activity. Contrasting with these massive behavioral changes, purely cognitive functions seemed relatively spared. On bedside examination, he appeared fully conscious and well oriented. Neuropsychological evaluation was within normal limits, except for tests exploring frontal lobe function (Stroop test, Wisconsin test) which were moderately impaired.

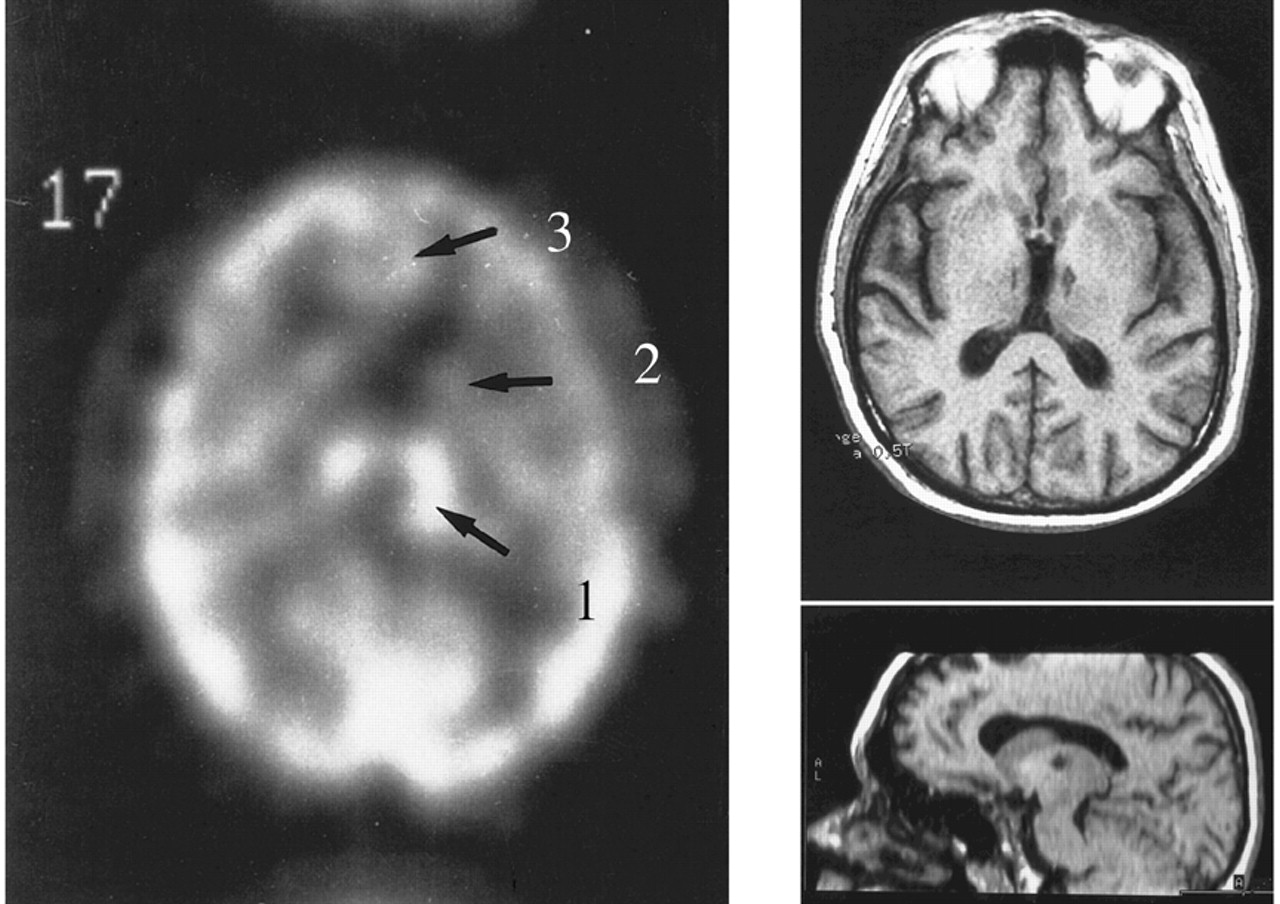

A T2-weighted spin-echo brain MRI scan showed multiple small zones of hyperintensity consistent with the definition of lacunes, located bilaterally in the basal ganglia regions. A single-photon emission tomography with Tc99-HMPAO showed a relative bilateral hypoperfusion in the basal ganglia regions without significant change in cortical (including frontal) blood flow.

Second case.

A 60-year-old university professor, widely respected in his scientific area, first consulted for the specific complaint of “decrease in interest.” His only remarkable medical event was a transient ischemic attack 3 months before and he had no known vascular risk factor. Neurological exam was normal except for moderate slowing of movements and poor spontaneous verbal expression. He had no personal complaint, but his family and professional entourage were struck by a dramatic decrease in activity and motivation. Formerly a hyperactive professional, starting working as soon as 3:00 a.m., he was described by his relatives as a very energetic and motivated person, with high-level investment in his activities, mainly his profession, but also various areas of interest (gardening, reading, fine cuisine, etc.). It was thus clear for anyone who knew him before that something had radically changed in the space of a few weeks. A follow-up of more than 7 years indicated that this radical change remained unaltered during all these years of observation. His own description of his new status was striking: “I just lack spirit, energy. I have no go. I must force myself to get up in the morning, I do things just because I ought to, without any liking or enthusiasm. I have no appetite, no need for eating; I only eat by principle.” During all these years, he occasionally could carry out some of his teaching duty, but only, he said, as a routine. He still used to go to board meetings but never taking the initiative of speaking. During this 7-year follow-up, he never complained of anything, never seemed bored or anxious, showed no sign of depression whatsoever. Remarkably, he never formulated the least question or complaint to his neurologist: actually, during these 7 years he never took the initiative of the conversation. A most embarrassing and impressive situation was his capacity to stay motionless and speechless during endless periods, sitting in front of the examiner, waiting for the first question, totally shut in a profound inertia and passivity, apparently unaware of the bizarreness of the situation. Once the neurologist had posed the first question, he usually answered very appropriately, although briefly. Invariably, the examiner was driven to ask a question which came out almost naturally: “what were you thinking of during all that time? Have you something you would like to say, but you cannot for any reason?.” Invariably, the answer was the same, each time as improbable “No, I’m just thinking of nothing, no idea, no question, no thought at all.” As we will see, this lack of spontaneous mental activity probably pertains to the core feature of the syndrome.

The remainder of the neurological and neuropsychological assessment was unremarkable, with high level of intellectual functioning, normal concentration and visuoconstructional abilities, strictly intact memory, no extrapyramidal signs except poor facial expressiveness, the only significant deficit being on the Wisconsin card sorting, which was markedly impaired, the patient failing to find the first criterion after 50 trials. A brain MRI scan showed multiple bilateral small lacunar infarctions, strictly located to the paraventricular regions, especially damaging the head of the caudate bilaterally. There was neither cortical atrophy, nor white matter changes in the frontal lobes.

Thus, what these two patients had in common was not only this surprising contrast between a profound behavioral change with intact intellectual functioning, but also a very similar lesion pattern, of common origin—lacunar infarcts—which most crucially were strictly restricted to the caudate nuclei. In other terms, this appeared as a new anatomoclinical syndrome, reminding us of the early concept of athymhormia. I will not discuss here the etiological features common to these observations, although it may be of some interest for clinical practice, to concentrate on their contribution to the description of a new neurological entity. Indeed, the same ingredients were present: a striking reduction in spontaneous motion and speech, with subjacent “mental emptiness,” a loss of interest for previously motivating activities and, maybe the crucial point, an apparent flatness or at least poor expressiveness of affect. This latter point had obvious implications: first, from a clinical point of view, that the patients must not be depressed, since depression, even that occurring after cerebral focal lesions,

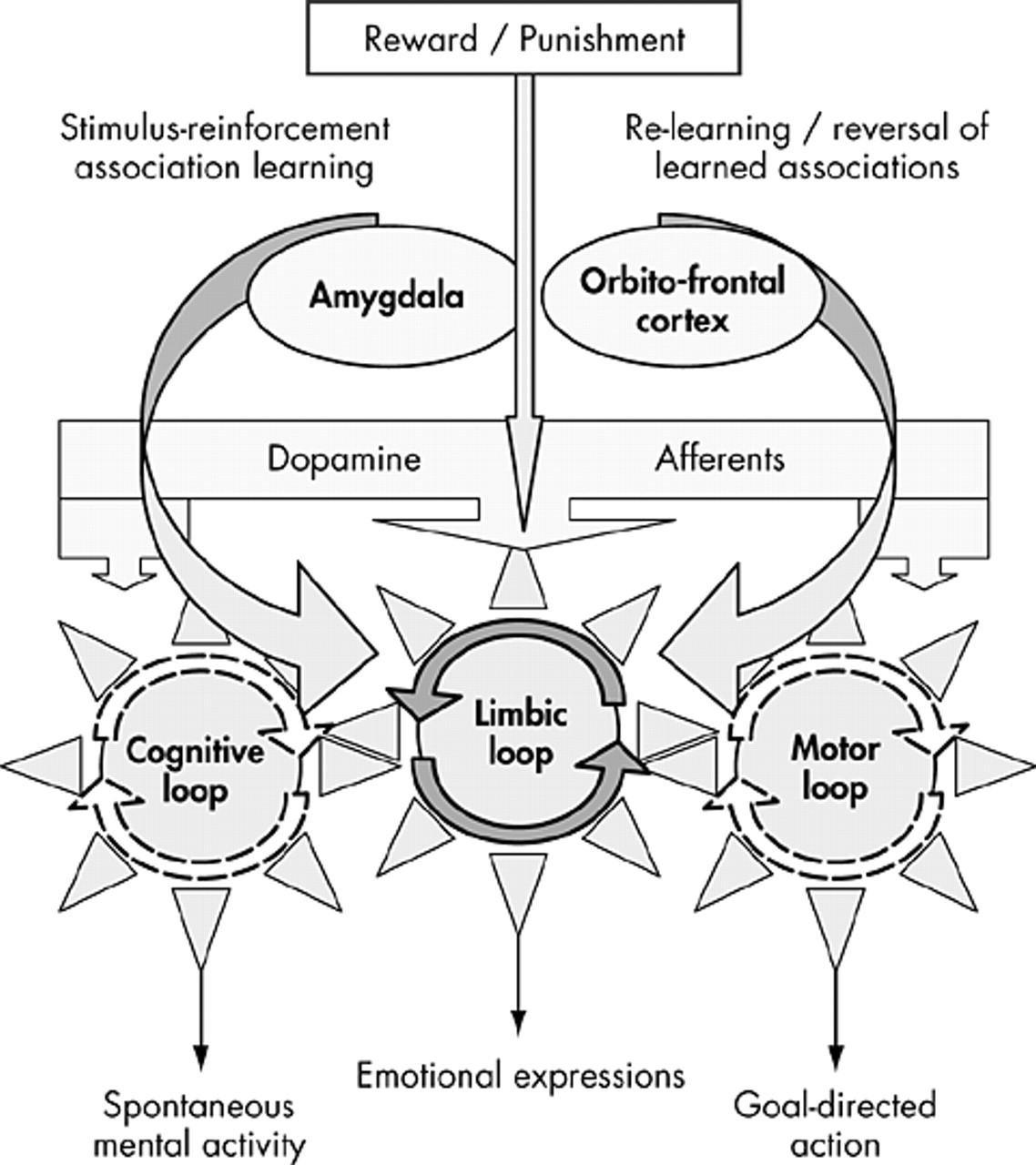

18 is necessarily accompanied with the inner experience of sadness and negative thoughts, which were notably absent in our patients, and second that, beyond an apparent pathology of action, movement or speech, the problem was to be sought clearly elsewhere, probably upstream, at the emotional (i.e., limbic) level.

A Striking Resemblance

A few years earlier, another French group, that of Laplane in Paris, had successively reported before the French Society of Neurology in La Salpêtrière Hospital, two cases of a very similar behavioral syndrome which was ascribed to damage to another subcortical structure: the globus pallidus.

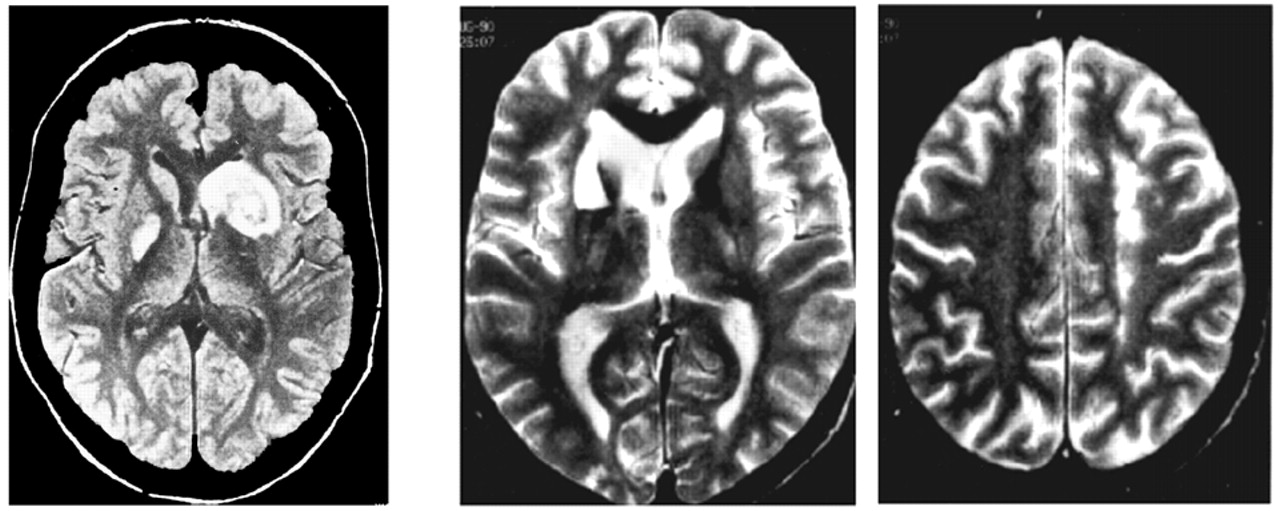

19–21 The first case was due to a wasp sting, the other to carbon monoxide poisoning.

At this time, since MRI was not yet available, pallidal involvement was only suspected on CT scan and the exact location of deep brain damage was difficult to ascertain. In both cases however, the clinical features were quite similar, yielding a singular picture of major motor and behavioral inertia and loss of spontaneous mental activity, apparently due to bilateral but disproportionately small brain lesions. These authors mainly focused on a compulsive behavior, mimicking obsessive-compulsive disorder, also present in the same patients (e.g., in one of them an “absolute necessity” to count until reaching a multiple of nine). In fact, such behavior later proved to be nonessential to the diagnosis.

In their first patient, these authors described a total motor inactivity without motor weakness, associated with a very strange state of “mental emptiness,” i.e., absence of spontaneous mental activity, without anxiety or particular suffering, and with otherwise surprisingly intact intellectual capabilities. Discussing the co-occurrence of loss of physical and psychic activity, and chiefly emphasizing the fact that motor as well as intellectual aptitudes were spared, the authors

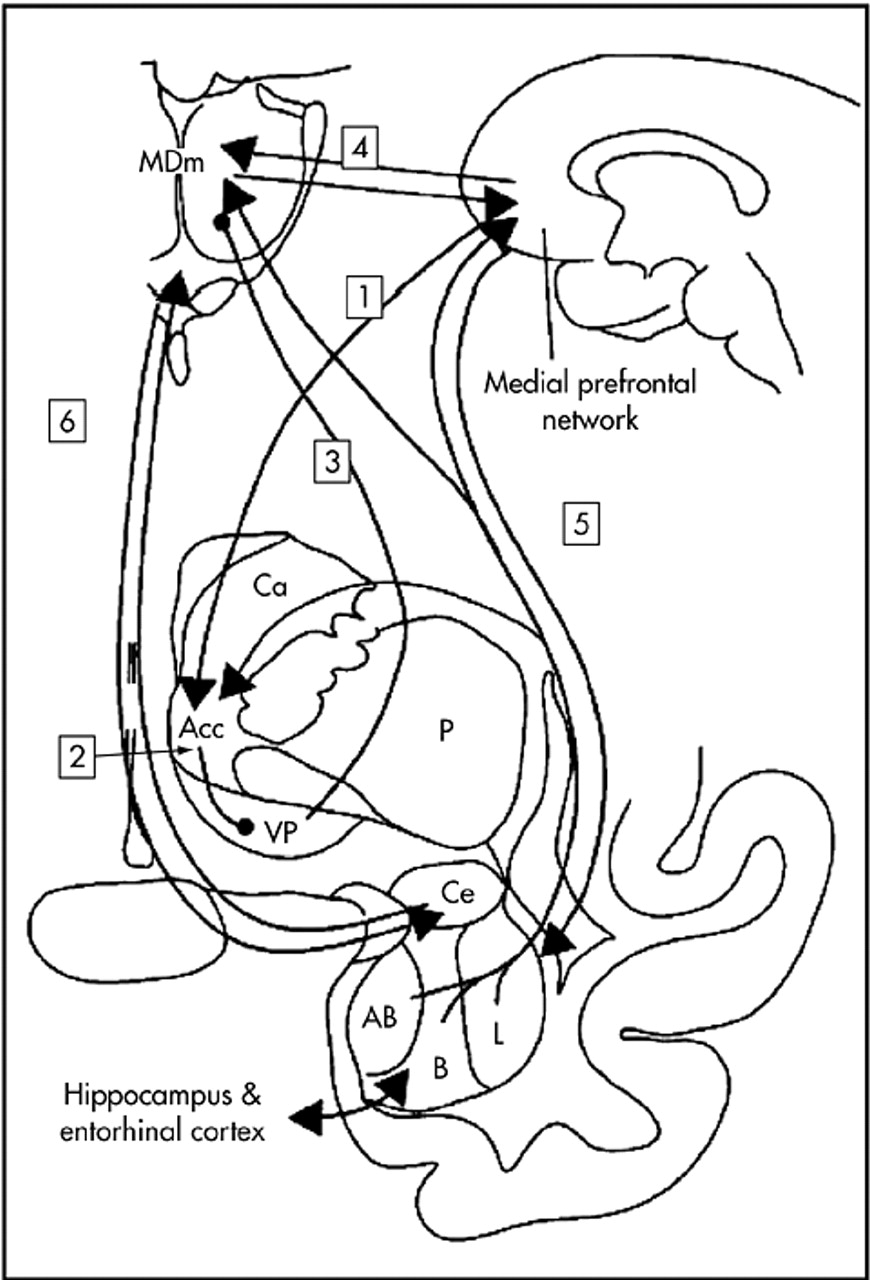

19 hypothesized an impairment of an “auto-activation system for psychic, intellectual and affective life.” According to this view, the basal ganglia would play a dual role in motor and psychic activity in such a way that impairment of this system would suspend spontaneous action as well as mental activity, possibly giving rise to compulsive behaviors. In their following paper,

20 they reported a similar case due to carbon monoxide intoxication. Here again, the patient was totally inactive but acted properly on external command, and displayed “pseudo-compulsive” symptoms. In this case, CT scan data were more convincing, showing bilateral pallidal hypodensities, leading the authors to postulate a hitherto unsuspected role for the globus pallidus in psychic self-activation mechanisms. Laplane also pointed out some similarities between this syndrome and various psychiatric conditions such as severe depressive states, obsessive-compulsive disorders and certain forms of schizophrenia.

Shortly after these articles were published, Ali-Chérif et al.

22 in Marseille extended Laplane’s findings to three new cases with pallidal lesions,

22 all three being due to carbon monoxide intoxication, and focused their description on the comportmental and mental changes in their patients, thus providing a confirmation of the role of the globus pallidus in these aspects of mental functioning. Following is the description given by Ali-Chérif et al. of one of their cases:

The essential semiological finding presented by these two patients consists in a profound inertia which is observable not only in motor activities underlying action on the outer world, but also in mental activity. Action is impaired in its initiation and in maintenance as well. Unless animated by a demand or an order coming from outside, no activity is carried out, even the simplest and the most habitual ones.…Action is also impaired in its progress since it tends to stop unless kept up by external stimulation. Contrariwise, if stimulation is sufficient to give rise to any activity, the latter is always correctly performed.

As an example of the impressive disorder of spontaneous action, they cite the case of the youngest patient of their series, a 19-year-old woman whom her parents had left in the morning on the central square of the small village they were living in, in Corsica, seated on a bench “to have a little rest before getting back home”; several hours later, actually after sunset, she was found exactly at the same place where she had stayed “without budging an inch” during all the day. On another instance, the same patient was found by her parents with heavy sunburns on the beach at the very same place where she laid down several hours before, under an umbrella: intense inertia had prevented her from changing her position with that of the shadow while the sun had turned around.

It must be noted that neither in Laplane’s nor in Ali-Chérif’s reports was any mention made of the terms motivation or motivational disorder. Instead, both authors insisted on the fact that patients were spontaneously inactive and inert but that adequate activity might be obtained from external demands or stimulations, thus pointing out the contrast between impaired self-activation and intact heteroactivation of behavior (“loss of auto-activation”). Also, both authors remarked on the conspicuous similarity between the motor and mental components of the syndrome, whereby the deficit seems to affect both activities inasmuch as they are self-initiated. (Actually, this dichotomy between self- and heteroinitiated acts or thoughts appears not to be totally correct since, in some cases, even external stimulation sometimes fails to yield an appropriate behavior.)

Another aspect pointed out by Ali-Chérif and only marginally alluded to by Laplane, and which may be of considerable importance, is the usual coexistence of impairment in still another domain of mental life, i.e., affect and emotion. “Affectivity is equally impaired, at least in the domain of expression of affects, and this ‘

grande indifférence affective’ is regularly pointed out by the patient’s relatives.”

22In fact, it was clear to us that there must exist a purely emotional component to the syndrome, distinct from and probably upstream to its most obvious and directly observable behavioral expression. Along with the observation of new patients, we acquired the conviction that the crucial pathophysiological point was to be sought at the level of emotional regulation and affective processes, as will be discussed below.