The deleterious effect neuropsychiatric symptoms have on the course of illness, level of care, and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been well documented.

1 Previous studies,

2,3,4 however, have tended to focus on positive (e.g., agitation, delusions, hallucinations) rather than negative symptoms (e.g., avolition, apathy), even though negative symptoms are reportedly more prevalent and contribute significantly and independently to the rate of decline in dementia.

5 Preliminary results from recent clinical trials treating a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with AD suggest that an atypical antipsychotic may provide broader efficacy with less adverse reactions than conventional neuroleptics.

6 To date, however, there have been few studies that have examined the efficacy of pharmacological agents including atypical antipsychotics in treating negative symptoms in AD.

7We report the findings from an 8-week, open-label trial conducted to evaluate the efficacy of olanzapine in treating negative symptoms. Subjects were recruited from a convenience sample at a university-based dementia program. Eligibility was limited to patients age 50 or older who were diagnosed with AD, according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) criteria, and who exhibited untreated neuropsychiatric symptoms, as evidenced by the Behavioral Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Scale (BEHAVE-AD).

8 Using a protocol approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board, decisional capacity was determined. Consent or assent was obtained from subjects, and consent was obtained from family caregivers. Fourteen patients (8 women) and family caregivers enrolled in the study, with one subject dropping out after week 1, following hospitalization for a preexisting cardiac problem.

Olanzapine was started at 2.5 mg-per-day, increasing in weekly 2.5-mg increments. If tolerated, the dose was maintained at 7.5-mg-per-day for 3 weeks prior to increasing to the next dose. Any dose was decreased by 2.5-mg-per-day if the subject or caregiver indicated an adverse reaction. The average olanzapine dose during the treatment phase was 6.2 ± 1.9 mg-per-day, with a range from 2.5 to 10.0 mg. Primary outcome measures included the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)

9 and the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES),

10 which were administered during weeks 1, 5, and 9. Safety measures were collected weekly and included the AMDP-5,

11 Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS),

12 and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale.

13 Baseline to endpoint data were analyzed using Student’s t tests.

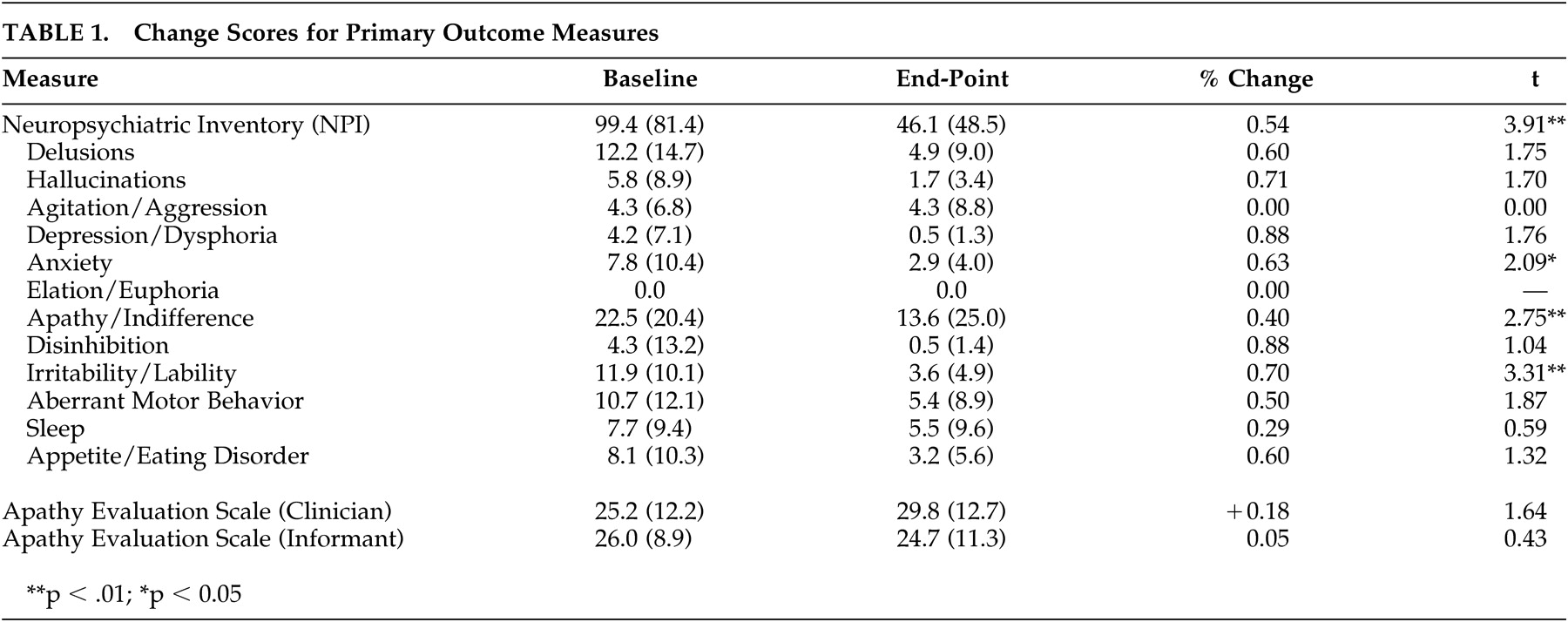

A total of 13 dyads (93%) completed the study. Mean length of AD was 3.7 years ± 1.7, with a consensus staging of early to moderate severity (CDR =1.4 ± 0.5). Overall results revealed a 54% reduction (p<0.01) in neuropsychiatric symptoms, with 10 of the 12 dimensions rated as improved at endpoint (

Table 1). Caregivers reported a significant decline in subject levels of apathy/indifference (p<0.01). Despite overlap between NPI apathy and AES scale items, AES ratings did not result in significant change. One factor that may account for this discrepancy is that NPI scales consider frequency and severity of symptoms in calculating a score, while the AES only assesses frequency. Analysis of baseline to endpoint results revealed no significant change in subject blood pressure, weight, extrapyramidal symptoms, or associated movement problems.

In interpreting these findings, it is important to note that these data were collected from an open-label clinical trial without benefit of a placebo comparison group. Nevertheless, results from this study support previous research findings indicating that atypical antipsychotic agents are effective in treating positive neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with AD and provide nascent support for its use in treating negative symptoms. Moreover, olanzapine was well tolerated by all study participants. Therefore, these results suggest that the therapeutic profile for olanzapine may be particularly well suited for patients with AD experiencing a broad array of neuropsychiatric problems.