P arkinson’s disease, the second most common neurodegenerative disease, is often accompanied by neuropsychiatric complications, including depression. Prevalence estimates for depression in Parkinson’s disease typically range between 20% and 40%,

1 depending on the population studied, the types of depression included, and the criteria used for symptom attribution (i.e., inclusive versus etiologic criteria).

Approximately 20% to 25% of Parkinson’s disease patients are on an antidepressant at any given time, most commonly a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

2 The efficacy of SSRIs for the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease has not been demonstrated, as both placebo-controlled studies published to date yielded negative findings.

3,

4 A number of open-label studies with various SSRIs for the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease found treatment to be beneficial,

5 –

10 but results often were reported either for completers only or without outcome data.

5,

6,

8,

9In addition to questions about efficacy, concerns exist about the impact of SSRI treatment on motor symptoms. In non-Parkinson’s disease patients, SSRI-induced akathisia, dystonia, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia-like states have been reported.

11 In Parkinson’s disease, anecdotal experience

2 and retrospective reviews

12 suggest that SSRIs can worsen motor symptoms in some patients. The results of open-label treatment studies suggest that SSRI treatment does not worsen parkinsonism overall, but these studies analyzed data only for those who completed the study.

5,

6,

8Several other nonmotor disorders commonly co-occur with depression in Parkinson’s disease, including anxiety,

13 executive impairment,

14 psychosis,

15 apathy,

16 and affective lability,

17 but it is not clear whether they are affected by antidepressant treatment or moderate treatment response. Regarding anxiety, there is preliminary evidence that SSRI treatment improves anxiety symptoms in the context of depression in Parkinson’s disease.

10 Regarding cognitive function, SSRI treatment does not appear to worsen global cognition (i.e., Mini-Mental State Examination score),

10 but its impact on executive and memory abilities, specifically, has not been studied.

Escitalopram, the

S -enantiomer of citalopram, is approved for the treatment of major depression. At daily dosages of 10 to 20 mg, it is equivalent in efficacy to citalopram, has a low incidence of side effects, and has minimal drug-to-drug interaction.

18 These latter properties make escitalopram an attractive drug for use in Parkinson’s disease patients, who typically take multiple medications and experience numerous somatic symptoms. We report results of an open-label, flexible-dosage study of escitalopram treatment for major depression in Parkinson’s disease.

DISCUSSION

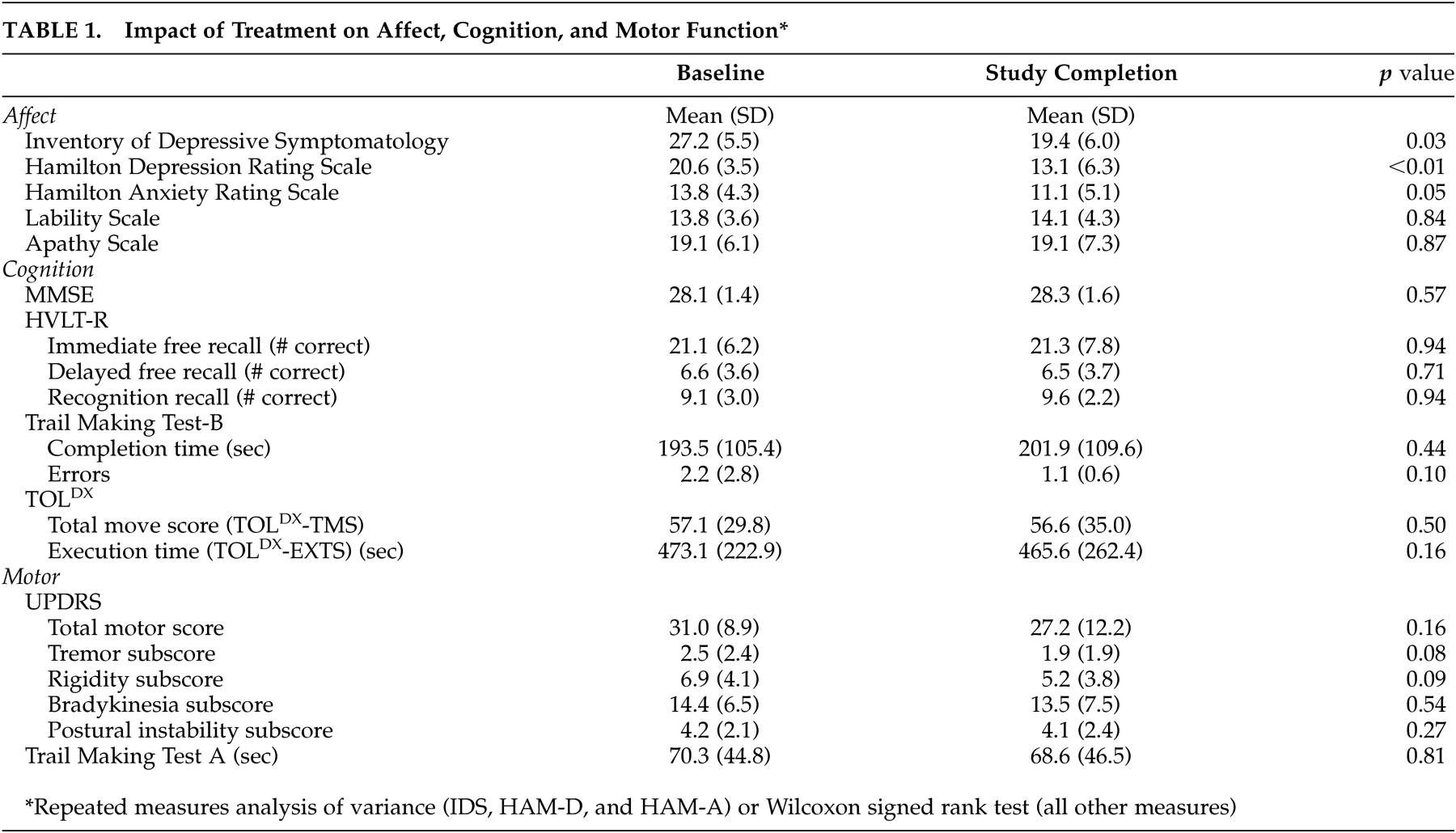

We found that open-label escitalopram treatment was well tolerated in the treatment of major depression in Parkinson’s disease, but most patients experienced only a partial response. Probing for moderators of treatment response, we found that certain nonmotor (greater apathy and poorer verbal memory) and motor (less postural stability) symptoms were associated with worse outcomes.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it was open-label with a small number of subjects, so any statements about the effects of treatment must be considered speculative. Second, the population was nearly all male and received specialty care. Third, the mean age was relatively high compared with other treatment studies for depression in Parkinson’s disease. Fourth, when probing for moderators of treatment response, a correction for multiple comparisons was not made. Thus, the results of this study cannot be generalized to the Parkinson’s disease population at large and are best used to generate hypotheses to test in future large-scale controlled studies.

A study-specific factor that may have contributed to the limited antidepressant response was the relatively high mean age of our sample compared with previous studies in Parkinson’s disease. There is research suggesting that very old (i.e., ≥75 years of age) depressed patients may have a more limited response to SSRI treatment.

33Though age may have played a role in our findings, our results suggest a limited response to SSRI treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Although most open-label antidepressant studies for depression in Parkinson’s disease have reported significant improvements in depression rating scale scores with SSRI treatment,

5 –

10 mean decreases in such scores have only been between 27% and 38%.

7,

9,

10 This is in contrast to results reported for large open-label studies in non-Parkinson’s disease elderly patients. For instance, in the largest open-label SSRI study to date for geriatric depression, the mean decrease in depression rating scale score was 61%.

34 In large-scale comparison studies for geriatric depression, both response rates and mean decreases in depression rating scale scores for patients treated with an SSRI are typically >50%.

35 –

38 If there is a limited response to SSRI treatment in Parkinson’s disease, possible explanations include disease-related pan-monoaminergic deficiencies and disruptions in key cortico-striatal pathways,

39 –

42 both of which may impair the ability of the Parkinson’s diseased brain to respond appropriately to traditional antidepressants.

Other possible explanations for the limited response to antidepressant treatment relate to complexities in the diagnosis and rating of depression in Parkinson’s disease. For instance, symptom overlap between depressive symptoms and core Parkinson’s disease symptoms is well known,

1 and diagnostic inaccuracies may have led to the inclusion of non-depressed patients in the study. In addition, numerous items on the IDS and HAM-D query about symptoms which occur commonly in Parkinson’s disease without depression (e.g., fatigue, insomnia, problems with concentration, decreased activity level, and psychomotor slowing), so suboptimal instrument specificity and sensitivity may have limited our ability to detect a treatment response. In support of this explanation, we did find that more patients were considered CGI-I responders than IDS and HAM-D responders, possibly because the CGI-I scale instructs the rater to make a global determination of improvement after weighing all relevant factors.

Regarding the time course of response, there was no significant improvement in depression rating scales or CGI-I ratings after 4 to 6 weeks of treatment. This suggests that Parkinson’s disease patients who have not responded to 6 weeks of SSRI treatment at an adequate dosage are not likely to respond to an extended trial.

The small change in HAM-A scores over time contrasted with previous SSRI studies reporting significant improvement in comorbid anxiety in depression in Parkinson’s disease.

9,

10 Similar to the possible limitations in using existing depression rating scales in Parkinson’s disease, the HAM-A may not be the ideal anxiety measure in Parkinson’s disease, as it is heavily weighted toward autonomic symptoms.

Escitalopram treatment did not adversely affect cognitive abilities, suggesting that SSRI treatment in Parkinson’s disease is well tolerated from this standpoint. This stands in contrast to concerns about using therapeutic dosages of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in this population.

43Our results were consistent with those of most previous open-label studies showing that SSRI treatment is well-tolerated overall and does not worsen motor function specifically.

5 –

8,

10 On the contrary, there was even a suggestion of improvement in tremor and rigidity symptoms. The study completion rate was 86% (12 of 14), and 83% (5 of 6) of patients treated with the highest recommended dosage tolerated it, suggesting that it is possible to use maximal SSRI dosages in this population.

Probing for possible moderators of treatment response, greater apathy and poorer free recall at baseline corresponded with a more limited antidepressant treatment response. It is possible that some patients classified as depressed, partly based on meeting DSM-IV criteria for anhedonia, actually were experiencing a loss of interest in the context of apathy, which typically does not respond to SSRI treatment.

44 Postural instability was the only Parkinson’s disease-related feature associated with antidepressant response. Perhaps patients with different subtypes of Parkinson’s disease, including those with prominent postural instability early in the illness, may be less likely to respond to antidepressant treatment than patients who have classical Parkinson’s disease symptoms only (i.e., tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia).

In conclusion, SSRI treatment in Parkinson’s disease appears to be well tolerated from all standpoints. Treatment lessens the severity of depression, though usually not enough to meet traditional criteria for response or remission. This suboptimal response may be due to either disease-related factors or to limitations in existing diagnostic and rating instruments when applied to depression in Parkinson’s disease. Though large-scale, placebo-controlled studies are needed to determine the efficacy of SSRIs in depression in Parkinson’s disease, it would be prudent both to explore alternate treatments for depression and to develop disease-specific depression assessment tools in this population.