A n association of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) with movement disorders (e.g., Tourette’s syndrome, Huntington’s disease, and Sydenham’s chorea) has been noted since the recognition of the latter.

1 The association of obsessive-compulsive disorder with parkinsonism was recognized during the encephalitis lethargica pandemic in 1917 when its occurrence temporarily provided insight on the importance of the basal ganglia and subcortical structures in movement disorders and OCD.

2,

3 Although neurology and psychiatry were distancing themselves from each other, it was recognized that disorders affecting the brain were not always clinically expressed in only one of these specialties.

1 In the next few decades, neurology focused more on neurobiology and evolved along a parallel yet completely separate line from psychiatry, which took a more biopsychological approach to understanding the human brain.

4 The development of structural and functional imaging in the 1980s led to a new era and provided an impetus for the reunification of the neurosciences. A spate of imaging studies in OCD ensued, which demonstrated evidence of the dysfunction of basal ganglia, especially caudate and frontal subcortical structures.

5 –

9 On the basis of these data, several authors have advanced models of basal ganglia thalamocortical circuits in which behavior is modulated by filtering irrelevant thoughts. Dysfunction of these circuits has been proposed in the pathogenesis of OCD.

10 –

12 From 1988 onward, case reports of basal ganglia lesions (diagnosed radiologically) associated with OCD were reported by several authors.

13 –

20 These reports spurred studies exploring the prevalence of anxiety disorders,

21 –

23 especially OCD, in Parkinson’s disease.

24 –

27 The studies were conducted on patients with established Parkinson’s disease, but the results conflicted—some authors reported association

22,

24,

26 and some reported a lack of association.

25,

27 Despite recognizing for nearly a century the possible association between OCD and parkinsonism, treatment needs of this special group remain relatively unexplored. Common therapeutic strategies for OCD like serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) might aggravate motor symptoms by stimulating 5-HT2 receptors and inhibiting dopamine release in the basal ganglia.

28 –

33 On the other hand,

L -dopa for parkinsonism is reported to aggravate compulsive and impulsive symptoms.

34 –

36 Patients exhibiting both obsessive and parkinsonian features thus provide a therapeutic challenge for the clinician. A few studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants in depression with parkinsonism but have not clearly commented on the effect on motor features.

37 –

40 OCD with parkinsonism, however, has not been satisfactorily addressed.

We present a naturalistic follow-up study of a group of late-onset OCD patients exhibiting parkinsonian signs who demonstrated a response to clomipramine, which might be considered a viable option for such patients.

METHOD

The patients were seen in the psychiatry clinic of a superspecialty tertiary care hospital in India over a span of 1 year. The hospital serves as the culmination point for many chronic and difficult-to-treat cases. This paper describes 10 patients who were diagnosed with OCD according to ICD-10 criteria and who showed parkinsonian signs (not deemed to be the effect of drugs). Two OCD patients without parkinsonian signs and one who did not undergo investigations were excluded from the study. Patients were rated on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, a 10-item scale that rates severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms,

41 and the Webster Scale for severity of parkinsonian features (bradykinesia, rigidity, gait, arm swing, tremor, and facial expression).

42 We obtained cardiology, prostate, and glaucoma tests and clearance for starting tricyclic antidepressants. Patients were started on a regimen of clomipramine following the principle of starting low and going slow, and the dose was titrated on the basis of clinical improvement and tolerability. We periodically rated the patients on the Visual Analogue Scale, the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and the Webster Scale through December 2006.

RESULTS

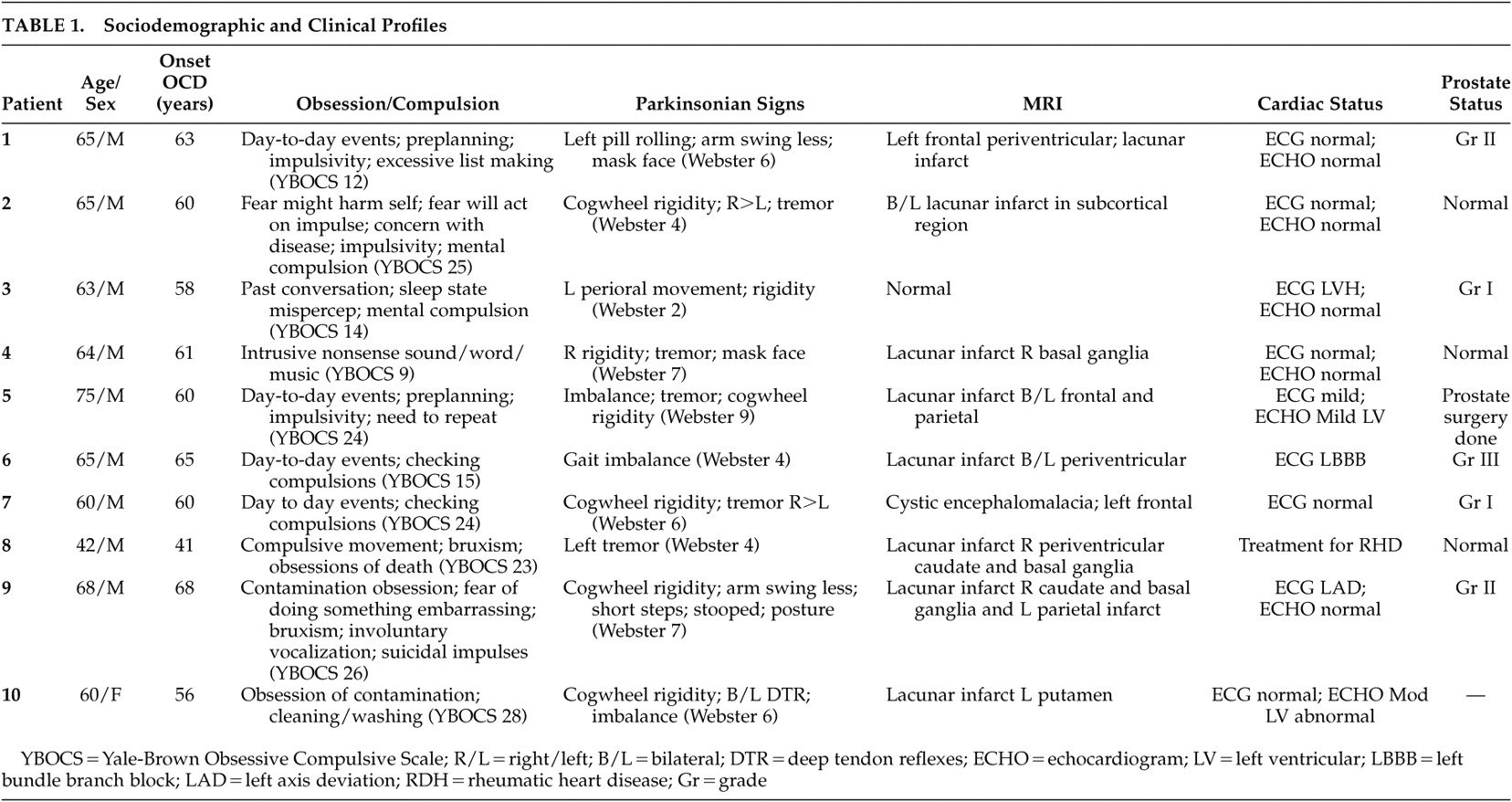

The sociodemographic and clinical profile of patients are summarized in

Table 1 .

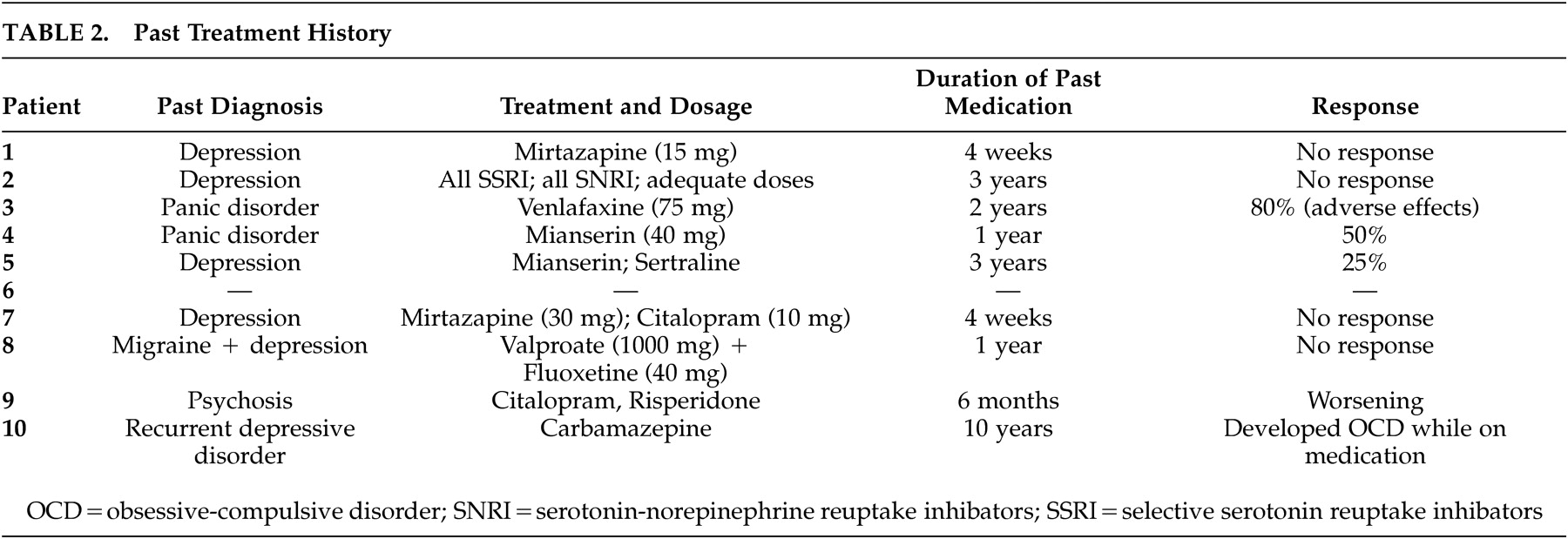

Table 2 demonstrates past treatment history. All patients had late age of onset for OCD, and most had demonstrable basal ganglia/frontal subcortical lesions.

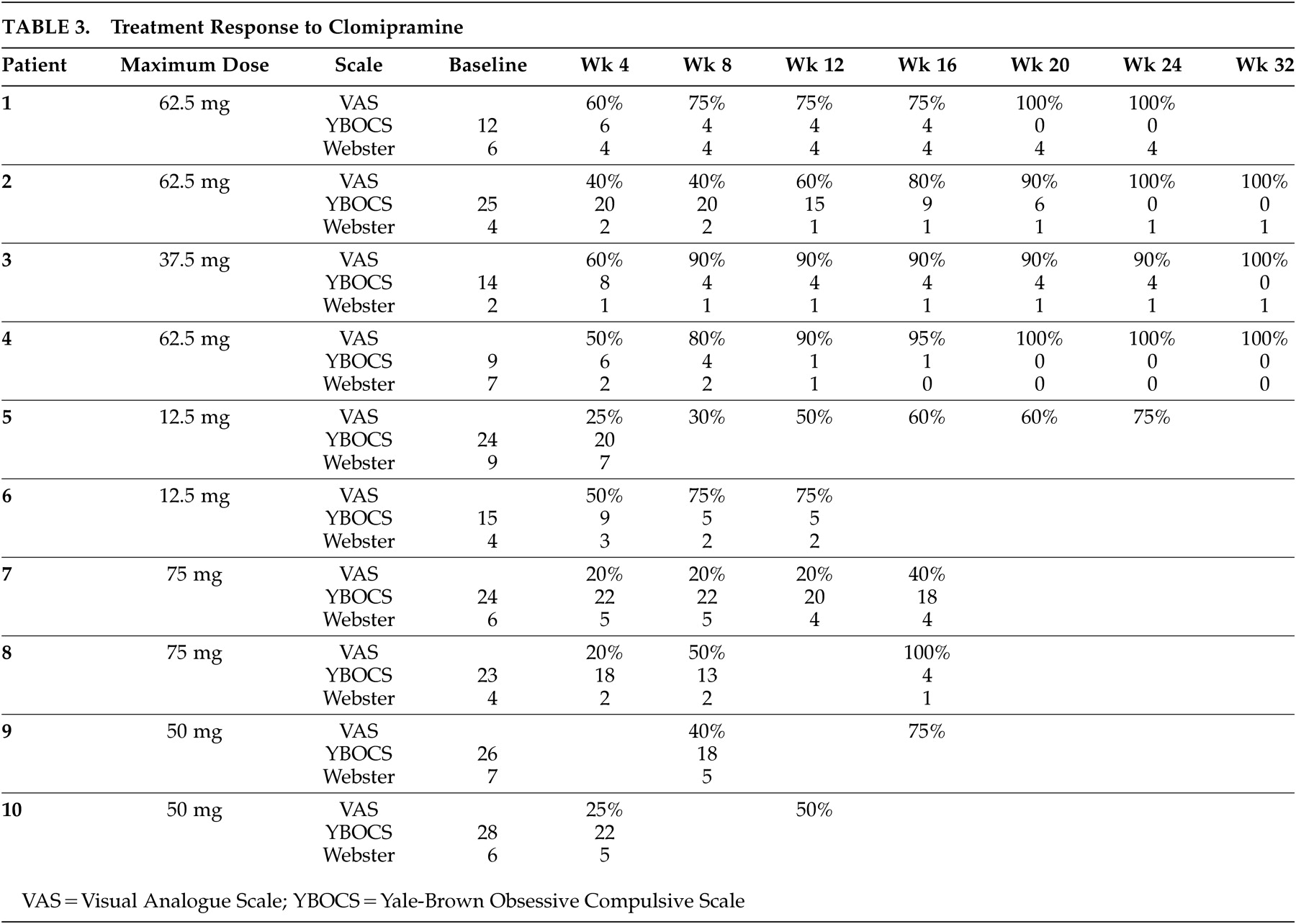

Table 3 shows patients’ robust and early responses to low doses of clomipramine.

DISCUSSION

This case series is notable as it presents a large series of patients presenting with late-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder exhibiting parkinsonian signs, with demonstrable lesions in the basal ganglia and/or frontal subcortical structures on MRI. All patients consulted a psychiatrist due to dysfunction resulting from OCD, and motor signs were elicited on evaluation. Potential confounding factors were avoided as their obsessive symptoms were not

L -dopa induced, nor were motor signs antipsychotic induced (patient 9, with history of antipsychotic treatment, had a 6 month drug-free interval before baseline assessment). The cases support the view that lesions of the basal ganglia could account for OCD as well as parkinsonism. Recognition of behavioral as well as motor features is essential, as such patients present a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. A diagnosis of late-onset OCD with parkinsonism is often shrouded in therapeutic nihilism as several authors have observed limited response to psychotropic medication

20 and aggravation of motor symptoms with SSRIs.

28 –

33 Our case study gives us reason to be hopeful, as all patients (including past nonresponders to SSRIs) showed an early and robust response to low doses of clomipramine without significant adverse effects. A concomitant decline in the Webster score was an added benefit. Sedative and anxiolytic effects of clomipramine obviated the need for benzodiazepines in all except two cases, avoiding drug interactions and the adverse cognitive effects of benzodiazepines noted in parkinsonism. Although our study is limited by the narrow population sample, it indicates a need for evolution of therapeutic strategies that address both behavioral and motor components of obsessive-compulsive disorder with basal ganglia lesions.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the 2nd Annual National Meeting of the Indian Association for Geriatric Mental Health in Chennai, India, on December 1-2, 2006.