D epression is the most common psychiatric complication after stroke.

1 On the other hand, it has been found that patients with depression have an elevated risk for stroke.

2,

3 The prevalence of poststroke depression at 1 month after stroke up to 6 years after stroke has varied from 12% to 60% as largely reviewed by Hackett et al.

4 as well as Paolucci.

1 Risk factors for poststroke depression include: female gender, age younger than 65 years, living alone, having had a recurrent stroke, being dependent on others, and institutional living 3 months after stroke.

5 It is well-known that depression is highly associated with suicide. Furthermore, suicidal thoughts after stroke are common; in a follow-up study of 300 patients, up to 11% had suicidal plans during the 2 years following their stroke.

6 A Danish study found that the risk of suicide is strongly increased after stroke, particularly among patients younger than 60 years old and among females.

7 The risk seems to be greatest within the first 5 years after stroke.

8The impact of poststroke depression on poorer outcomes among stroke patients is well known,

9 –

11 whereas the association between prestroke depression and prognosis among stroke patients has not yet been sufficiently recognized. Recently, a register-based study in the Netherlands with longitudinal data was published in which Nuyen et al.

12 found that patients with prestroke depression had a fivefold risk of being discharged to an institution instead of to their homes compared to patients who were not depressed. However, they did not study the possible effect of depression on the suicide process of these patients.

In this study we used a comprehensive database of all suicides committed in Northern Finland during the years 1988–2007 with information on all hospital-treated somatic and psychiatric disorders. We wanted to find out the following: the prevalence of stroke in suicide victims, whether depression is a risk factor for suicide, and the influence of prestroke depression on suicide process among victims.

METHODS

We examined all suicides (N=2,283) committed during the years 1988–2007 in the province of Oulu in Northern Finland. Data on age, gender, suicide methods, and previous suicide attempts and abuse of alcohol at the time of the suicide were based on the death certificates from forensic medical-legal investigations. The Ethics Committee of Oulu University approved the study protocol. The diagnoses of subjects and hospital admissions of suicide victims were obtained from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (FHDR).

13 The FHDR covers all treatment in general, private, mental, military, and prison hospitals, as well as the inpatient wards of local health centers nationwide.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) was used as follows for cerebrovascular diseases: ICD-8 and ICD-9 codes 432–438 and ICD-10 codes I63-I69 and G45. The victims without stroke were dichotomized to two groups as follows: victims younger than 55 years old and those 55 years or older. Based on the epidemiology of stroke prevalence, stroke is known to increase markedly after 55 years old.

14 Psychiatric disorders were categorized as follows: any psychiatric disorder (ICD-8 and ICD-9: 290–319; ICD-10: F00.00-F99) and depression (ICD-8: 2960, 2980, 3004; ICD-9: 2961, 2968, 3004; ICD-10: F32-F34.1).

The methods for suicide among study subjects were categorized as violent if the method was hanging, drowning, shooting, wrist cutting, jumping from a height, and traffic. Nonviolent methods were poisoning, gas, and other methods. Acute alcohol intoxication was detected in the medical autopsy by a doctor in forensic medicine and entered on the death certificate.

Statistical Methods

Statistical significance of group differences in categorical variables was examined with Pearson χ 2 -test or Fisher’s exact test. Cox proportional hazard model was used to examine the likelihood of dying of suicide after stroke in the following three subgroups: prestroke depression, poststroke depression, and no depression after adjusting for age and gender of the victims. All statistical tests were performed with SPSS for Windows, version 13.

RESULTS

Of the total suicide data population (N=2,283), 3.4% (n=75) had suffered from stroke during their lifetime.

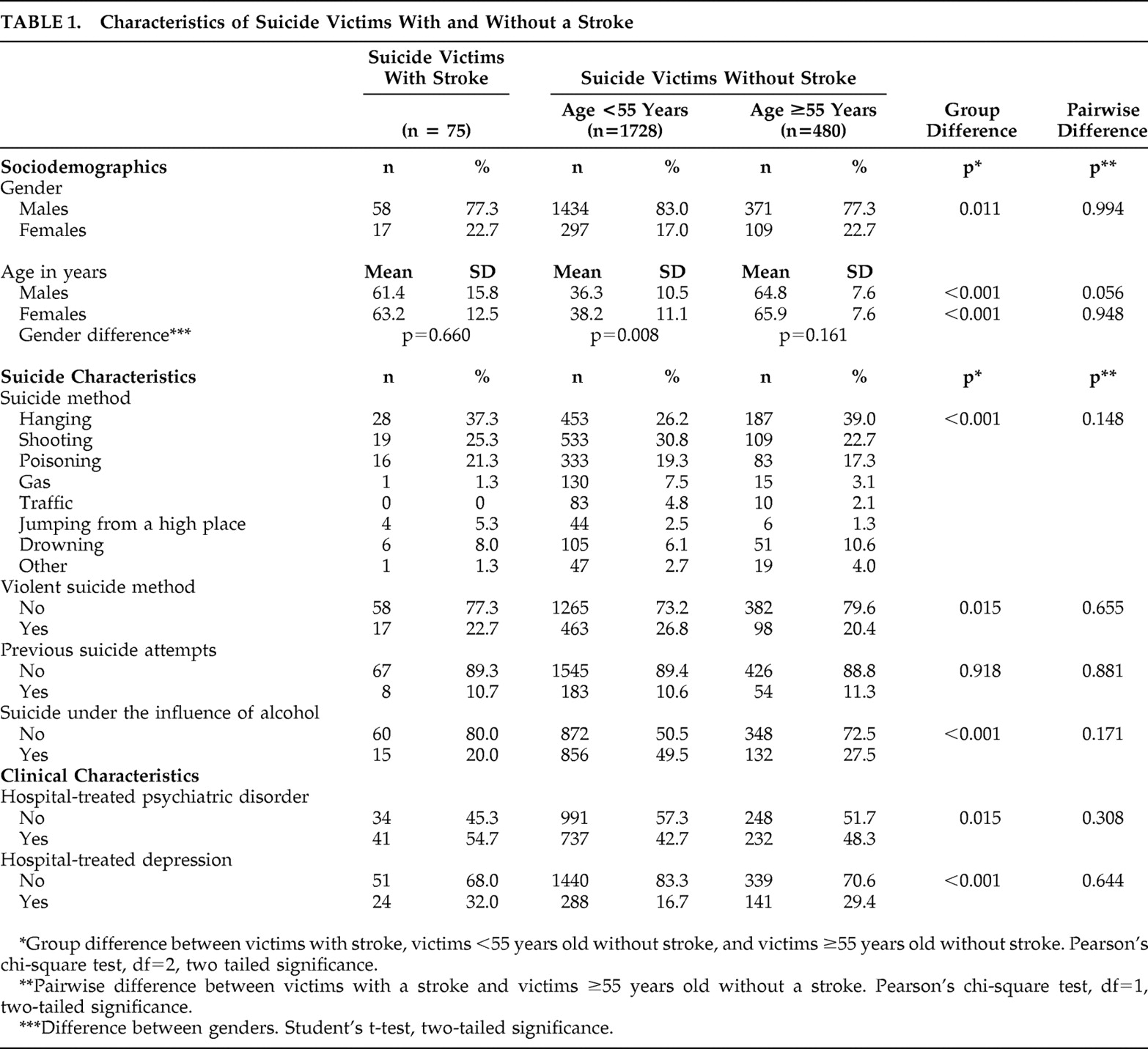

Table 1 summarizes the clinical and suicide characteristics of the victims with and without stroke in two different age groups. When comparing the three study groups, statistically significant differences were found in age, gender, suicide method, alcohol contribution to suicide, hospital treated psychiatric disorder, and depression. When comparing the suicide victims with stroke with the age group of 55 years or older, no statistically significant differences were found in pairwise comparisons in the background characteristics.

The majority of the victims with stroke (80%) were not under the influence of alcohol at the time of suicide. The most common suicide method among stroke victims was hanging (37.3%); 32% of the victims with stroke had been hospitalized due to their depression (

Table 1 ).

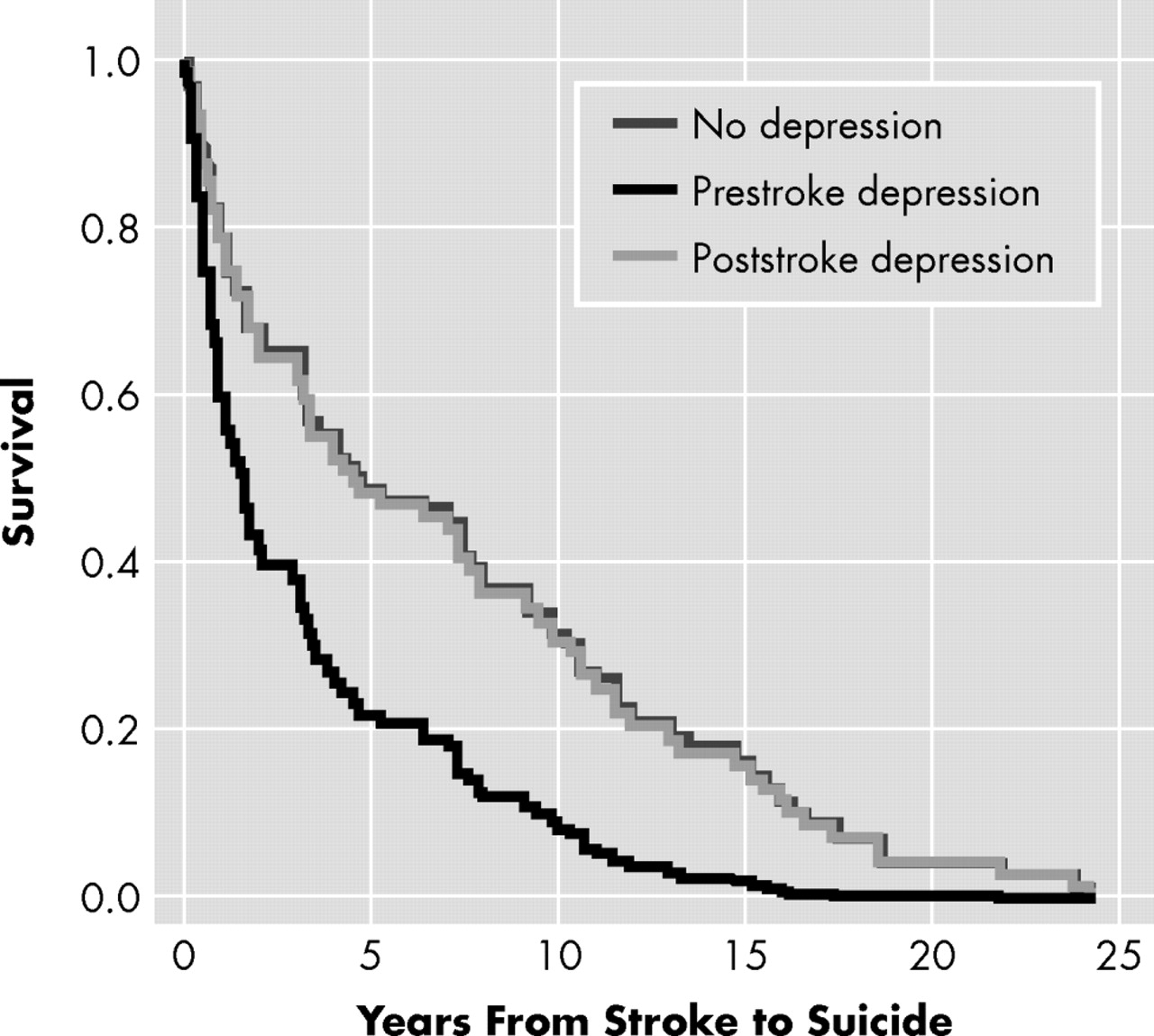

Based on the Cox proportional hazard regressions,

Figure 1 presents the survival estimates from stroke to suicide among victims with depression. The age- and sex-adjusted hazard of suicide after stroke was 2.2-fold among victims who had suffered from prestroke depression (adjusted hazard ratio=2.16, 95% CI=1.07–4.37, p=0.033) compared to those without any lifetime depression. The elevated hazard of suicide was not seen among victims with poststroke depression compared to those with prestroke depression (adjusted hazard ratio=1.03, 95% CI=0.56–1.91, p=0.927).

Furthermore, six of the stroke victims whose depression had been assessed before the stroke (55%) committed suicide within 2 years after having a stroke. Correspondingly, only three of the suicide victims with poststroke depression (23%) and 19 of those with no lifetime depression (37%) had committed suicide within 2 years after their stroke.

DISCUSSION

We found that 3.2% of all the subjects in this large population-based suicide data set from Northern Finland had suffered from stroke. Our findings showed a low prevalence of stroke in this suicide database compared to earlier literature. It has previously been shown that the percentage of suicides in persons with stroke may be as high as 7.2% in the Danish population.

7The suicide victims with stroke were about 63 years old. They were 20 years older and more often female compared to the other victims. Our findings are in line with a former study

7 in which stroke patients in the age groups up to 60 years old and women were shown to have a significantly increased risk of suicide. In general, suicide has been found to be associated with older age and somatic diseases.

15 –

17The major finding of our study in this suicide data set was that prestroke depression was associated with a significantly shorter survival after stroke. On the other hand, the survival time among victims with poststroke depression did not differ from that of nondepressive ones. Formerly, the timing of depression in relation to stroke was mostly diagnosed as manifesting itself after stroke and thus named poststroke depression.

1,

4,

9 –

11 However, it has been shown that one in three stroke patients were using antidepressants at the time when the stroke occurred.

2 It is well known that depression is a recurrent disorder.

18 Thus, it is very likely that depression among stroke patients is not only “poststroke” depression, but a relapse of a recurrent depressive disorder. Poststroke depression has previously been found to associate with poor outcome and quality of life among stroke patients.

9 –

12 To our knowledge, this study is the first one so far in which prestroke depression has been shown to increase the risk of accelerated suicide among stroke patients. It has been suggested that in stroke patients with previous depression, stroke is more severe than in those without prestroke depression, which can also lead to decreased prognosis among stroke patients with depression.

12In this study about 70% of the stroke victims with prestroke depression had committed suicide within a 2-year period after stroke, compared to 30% of those with no depression or poststroke depression. Earlier, Teasdale and Engberg

8 pointed out that the increased risk period for suicide was 5 years after stroke. However, they did not take into account the possible accelerative effect of depression on the occurrence of suicide. We suggest that the increased risk of suicide should be monitored not only in the long-term follow-up but also particularly during the 2-year period immediately after stroke. Psychiatric consultation is therefore highly recommended for stroke patients with prestroke depression in clinical work at a neurological and neurorehabilitation unit when the follow-up of stroke is being designed. It is well known that recognition of depression and treatment with antidepressive drugs are the most important factors in suicide prevention.

19,

20In our study the victims with stroke were significantly more rarely under alcohol intoxication compared to other suicide victims at the time of committing suicide. This finding is interesting since it is known that in general, alcohol intoxication often contributes to suicide.

14 Furthermore, the suicide method among stroke patients was generally nonviolent. According to our findings, we suggest that among stroke patients, suicide is mainly committed without alcohol intake and is thus nonimpulsive and premeditated before the definitive accomplishment of suicide.

In this data set we found that stroke victims had significantly more often suffered from hospital-treated depression compared to the victims without stroke. Former studies have indicated that depression is a major comorbid psychiatric disorder among stroke patients both before and after their stroke.

1 –

4,

9 –

11 It has also been found that there is a significant association between earlier depressive symptoms and subsequent incidence of stroke.

21 –

23 The direct mechanisms behind this have not yet been clarified.

21 Multiple risk factors have been suggested to contribute to the association between preceding depression and stroke as follows: regulatory failure in the noradrenergic systems, increased adrenergic activity, and disturbances in neuroendocrine or immunology systems.

24 –

27 Further, increased levels of fibrinogen or abnormal platelet activation may lie at least partly behind the association of depression and stroke.

28 –

30 There are also behavioral factors common to both depression and stroke, such as low physical activity, smoking, or an unhealthy diet.

21As first described by Alexopoulos et al.,

31 vascular disease can precipitate, worsen, or complicate depression. The development of depression in the patients with vascular disease is based on a complex set of etiological pathways and interactive factors.

32 Vascular depression has also shown to be associated with executive dysfunction,

33 but the risk of potential increased suicide rates among these patients has not yet been studied.

The limitations of our study were that all diagnoses were obtained from the national register-based information on hospital treatments, and thus only psychiatric disorders severe enough to require hospitalization were analyzed. It is thus possible that the suicide victims may therefore have been treated for mild psychiatric disorders but became disease-free subjects in our study setting. Unfortunately, there are no common national registers for outpatient treatment in Finland, and the percentage of wrongly classified patients, even if small, remains unknown. The number of victims in each subgroup according to depression state was rather small. Also we had no control population, and thus we could not compare the rate of suicides to population based studies. In addition, we were not able to evaluate the severity of stroke in the victims.

The strengths of the present study were that all suicides committed during the study period in the province of Oulu, a geographically large area, were included and evaluated. Thus, the study was limited neither to a certain age group nor to otherwise incomplete suicide data. In addition, the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register has been shown to be a reliable source of information in scientific research on various kinds of hospital treatments of patients.

13