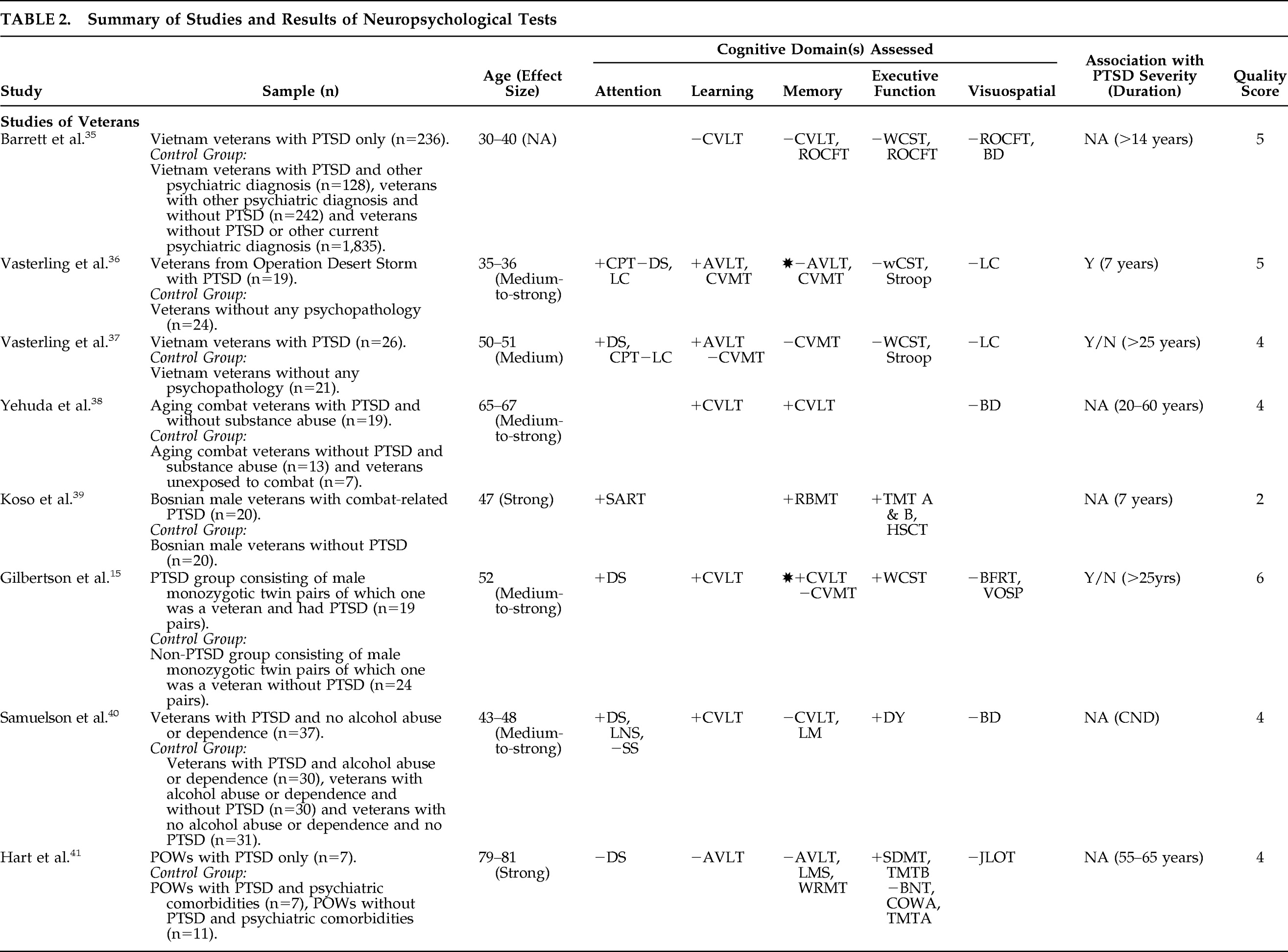

Studies of Veterans

Studies of veterans are most common (n=8). Age ranges from 30 to 81 across these studies, and approximate time since trauma ranges from 7 to 65 years.

Barrett et al.

35 examined cognitive impairment in one of the largest samples of veterans from the Vietnam Experience Study. Vietnam veterans with only PTSD (N=236) were compared with those with PTSD and other psychiatric disorders (N=128), with other psychiatric disorders without PTSD (N=242) and without PTSD or other psychiatric disorders (N=1,835). Several neuropsychological tests were used, but none was significantly associated with PTSD after adjusting for demographic and military covariates including combat exposure. The authors concluded that cognitive deficits in PTSD are most likely secondary to comorbid mental health disorders.

Vasterling et al.

36 examined memory and attention in veterans who were mobilized for Operation Desert Storm. They compared veterans with PTSD (N=19) to psychopathology-free veterans (N=24), using a large battery of neuropsychological tests. Their findings include problems in sustained attention on the Continuous Performance Test commissions (p=0.023;

d=−0.64, r=−0.30) and learning on AVLT trials (p=0.025;

d=−0.84, r=−0.39) and Continuous Visual Memory Test learning phase (p=0.004;

d=−0.90, r=−0.41) in veterans with PTSD. A medium-to-strong effect size was observed for these significant associations. These cognitive impairments were found to be associated with severity of PTSD symptoms, especially reexperiencing and avoidance. Memory impairment was also present on delayed recall but was not significant after controlling for initial learning.

Vasterling et al.

37 did a similar study of Vietnam veterans who served in war zones, with similar results. Veterans with PTSD (N=26) were compared with veterans without any mental disorders (N=21). Impairment in attention was noted in veterans with PTSD on Digit Span (DS) (p=0.03;

d=−0.05, r=−0.03) and Continuous Performance Test hits (p=0.04;

d=−0.68, r=−0.32). Although total learning was not impaired on the Continuous Visual Memory Test (p=0.88), total recalls on Trials 1–5 were significantly impaired on the AVLT (p<0.01;

d=−0.70, r=−0.33) in these individuals. Impairment in both cognitive domains had a good effect size. Substance abuse and PTSD symptom severity were also taken into account in this study. The authors concluded that cognitive impairment is associated with PTSD, independent of intellectual functioning.

Yehuda et al.

38 studied learning and memory in aging combat veterans who were age 65 or older. Although the PTSD-positive group (N=30) was significantly different from the nonexposed group (without trauma; N=15) in memory and learning, when compared with the PTSD-negative group (with trauma) (N=20) this difference was not significant. However, in an analysis of a subsample population after excluding those with a history of substance abuse, they did find significant differences in the PTSD-positive (N=19) and negative (N=13) groups in learning (p=0.03;

d=−0.52, r=−0.25) and delayed recall (p=0.01;

d=−0.85, r=−0.39) on the CVLT, with medium-to-strong effect sizes.

Koso et al.

39 investigated memory and executive function in Bosnian combat veterans. The group found significant differences in PTSD (N=20) and non-PTSD (N=20) groups on several neuropsychological measures. They concluded that veterans with PTSD showed impairment in attention on the Sustained Attention to Response Task (p<0.001;

d=1.34, r=0.56), memory on the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test (p<0.001;

d=−2.44, r=−0.77) and executive function on the Trail-Making Test A (p<0.001;

d=1.15, r=0.50), Trail-Making Test B (p<0.001;

d=1.51, r=0.60) and Hayling Sentence Completion Test (p<0.001;

d=1.41, r=0.58), with strong effect size.

Gilbertson et al.

15 compared combat-exposed Vietnam-era veterans with (N=19) and without PTSD (N=24) and their monozygotic twins. The authors assessed neurocognitive functioning and found that the verbal memory measure demonstrated a significant diagnosis main effect (Cohen's

d=0.77). Combat veterans with PTSD scored significantly lower in verbal memory (p=0.03) when compared with veterans without PTSD. Learning also demonstrated a significant diagnosis main effect (t=2.13; p=0.04). They also found significant diagnosis main effects on measures of attention (Cohen's

d=1.11) and executive function (Cohen's

d=0.89), but not in visual memory and visuospatial abilities. Combat veterans with PTSD scored lower in attention measures (p=0.006) and higher in executive dysfunction (p=0.009) than those without PTSD. Interestingly, veterans with PTSD did not differ significantly from their unexposed twin without PTSD on measures of verbal memory, attention, and executive function. Except for perseverative errors, none of the neurocognitive differences between PTSD and non-PTSD groups were clinically relevant. The authors suggest that cognitive deficits in PTSD are familial in nature and serve as a risk factor for PTSD in the aftermath of trauma.

Samuelson et al.

40 studied cognitive functions in veterans with PTSD and alcohol abuse. Subjects were divided into four groups, based on their PTSD and alcohol status, and their neuropsychological test scores were compared. There were 30 veterans in PTSD+/ETOH+ group, 37 veterans in PTSD+/ETOH− group, 30 veterans in PTSD−/ETOH+ group and 31 veterans without PTSD or alcohol abuse or dependence. All groups had been exposed to a similar level of trauma. On measures of attention, there was a significant main effect of PTSD on DS (p<0.0001;

d=−0.97, r=−0.43) and Letter Number Sequencing (p=0.01;

d=−0.85, r=−0.39) but not on Spatial Span (p=0.57). Similarly there was a significant main effect of PTSD on CVLT trials 1–5 (p=0.006;

d=−0.59, r=−0.29) but not on delayed recall (p=0.40) or Logical Memory I and II (p>0.2). Among other measures, Digit Symbol had a main effect of PTSD (p=0.001;

d=−0.76, r=−0.35) but not Block Design (p=0.6). All significant associations had medium-to-strong effect sizes. The authors concluded that verbal memory and attention were impaired in PTSD.

Hart et al.

41 tested World War II and Korean War veterans who were also prisoners of war (POWs). They compared POWs with PTSD-only (N=7) versus POWs with PTSD and other psychiatric comorbidities (N=7) and POWs without PTSD or psychiatric comorbidities (N=11). They found executive dysfunction with strong effect sizes on Symbol Digit (p<0.05; d=−1.83, r=−0.67) and Trails B (p<0.05;

d=1.08, r=0.47) in subjects with PTSD only when compared with POWs without PTSD or other psychiatric comorbidities. They suggest that cognitive impairments in PTSD may be related to comorbid conditions and higher IQ may protect against developing PTSD.

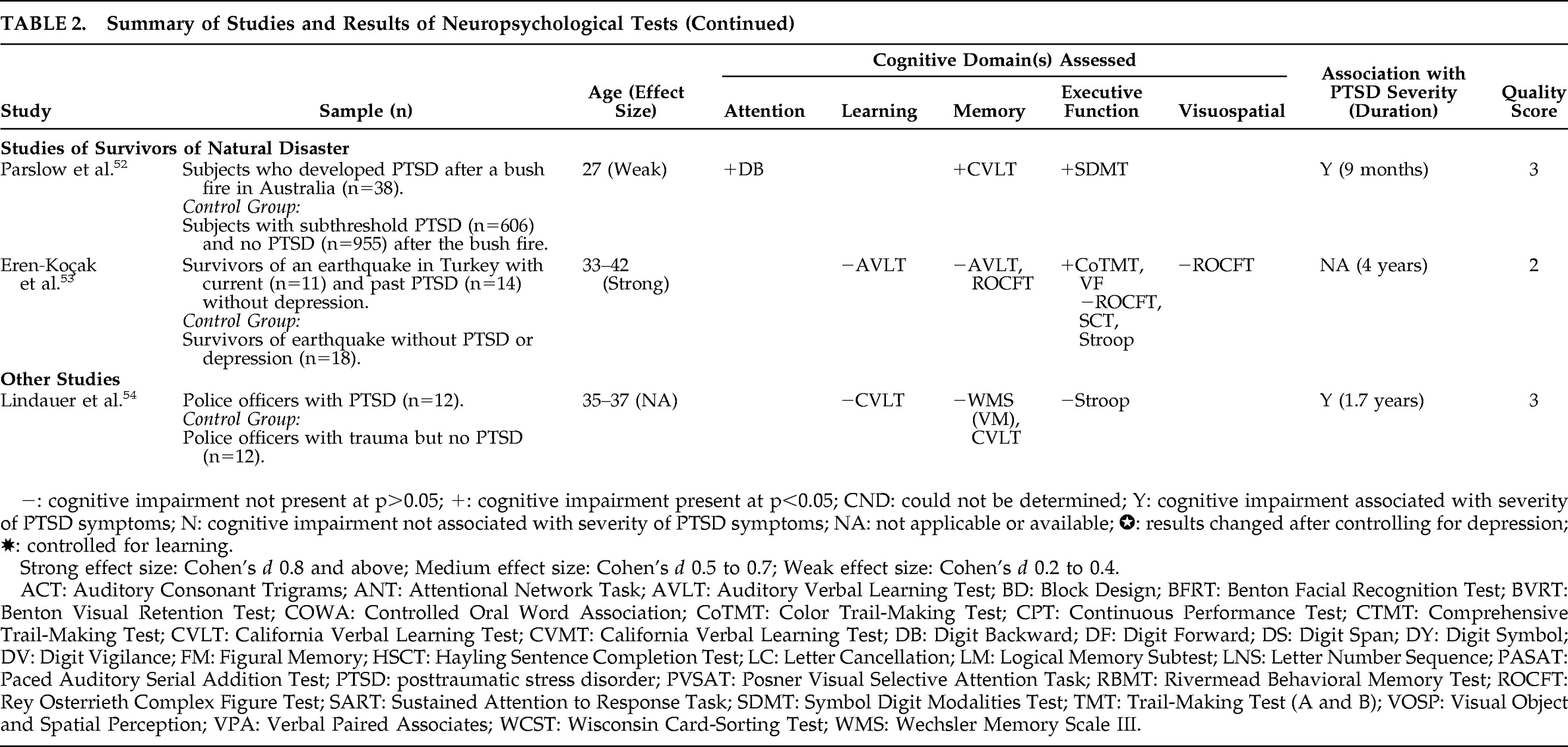

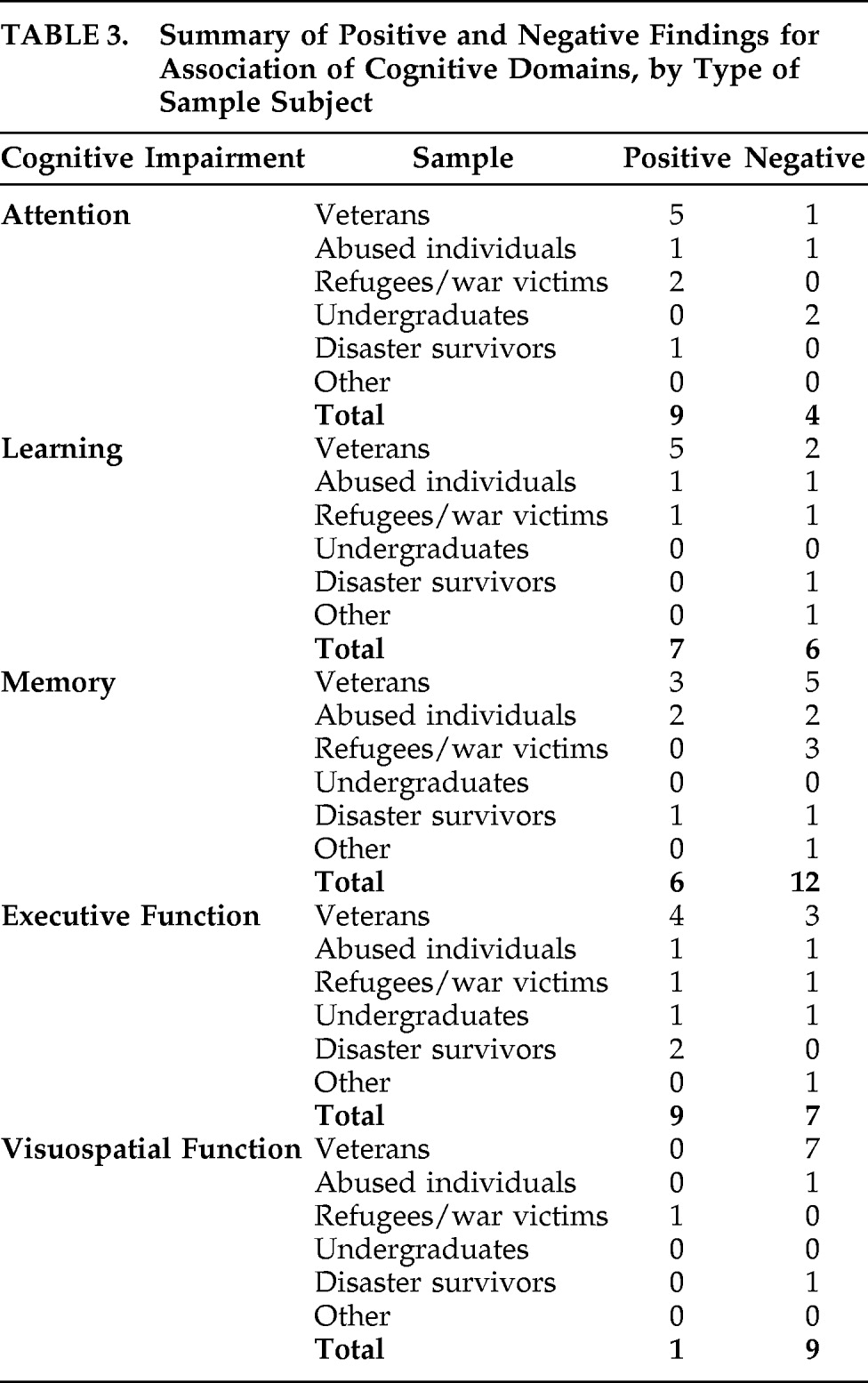

Results of studies examining cognitive differences between veterans with and without PTSD have been mostly positive, with medium-to-strong effect sizes. Only two studies did not find any significant cognitive impairment with PTSD after controlling for confounding factors such as learning. The rest of the studies were positive, especially for attentional measures (

Table 3). One reason might be the longer duration of PTSD in these studies.

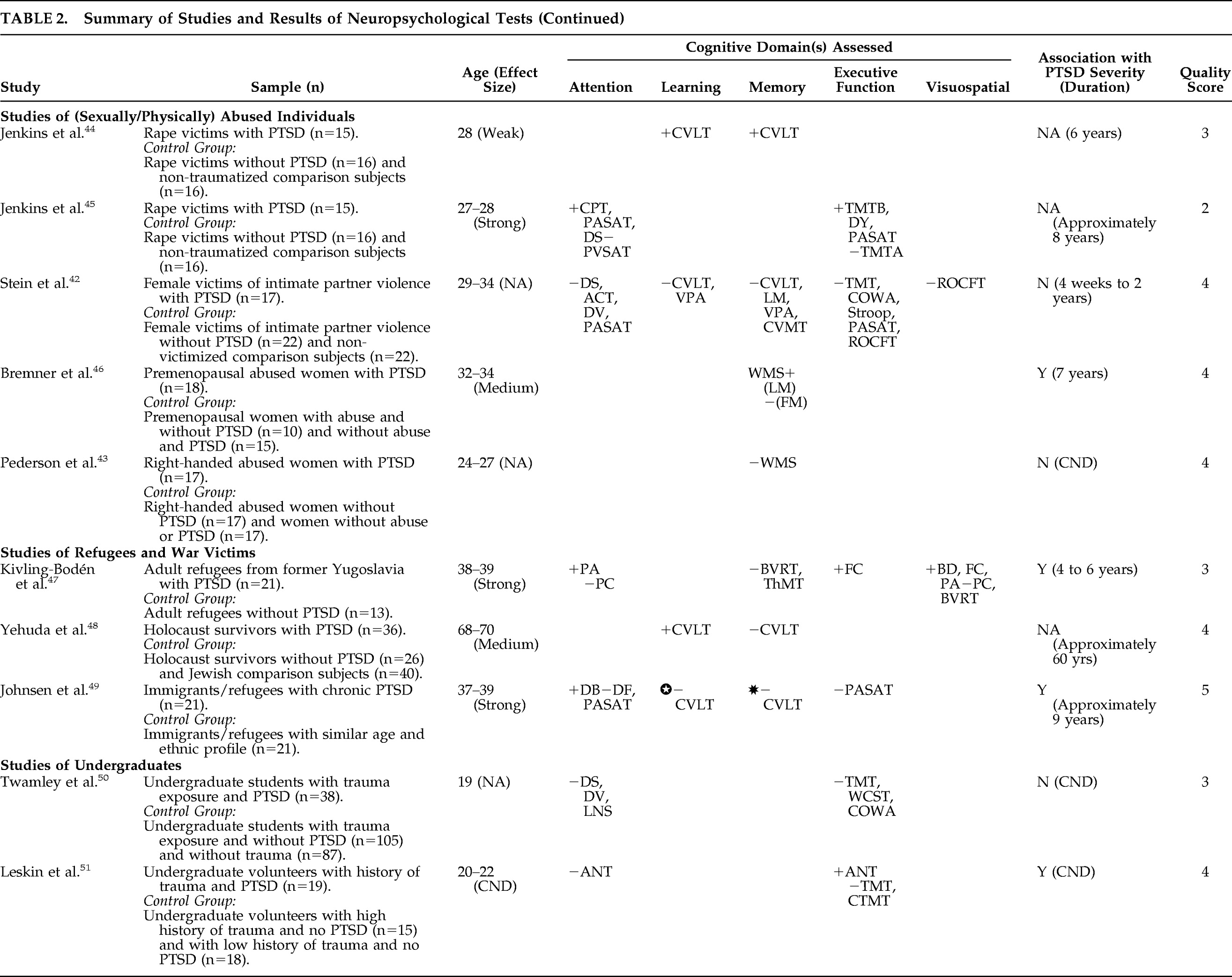

Studies of Abused Individuals

The second largest group of studies (five) focuses on sexually or physically abused individuals, mostly women. Their average/mean age range is between 24 and 34 years, with approximate time since trauma ranging from a few weeks to 8 years.

Stein et al. compared neuropsychological functioning in female victims of intimate-partner violence, with (N=17) or without PTSD (N=22).

42 The subjects underwent several neuropsychological tests, but results failed to show any significant differences between trauma victims with or without PTSD. The authors reported that cognitive deficits in these subjects were subtle, regardless of PTSD status.

Pederson et al.

43 correlated memory performance and hippocampal volume in women with a history of child abuse. They were divided into PTSD-and-abuse, abuse-only, and normal-control groups, with 17 subjects in each group. These subjects completed the Wechsler Memory Scale but did not demonstrate significant differences between groups with or without PTSD in immediate, delayed, and working memory.

Jenkins et al.

44 examined learning and memory in rape victims with (N=15) and without PTSD (N=16) relative to nontraumatized comparison subjects (N=16), 6 years after the initial trauma. They used CVLT and found that women with PTSD performed worse on number of words learned (p=0.02;

d=−0.28, r=−0.13) and long-delay free recall (p<0.01;

d=−0.24, r=−0.12) after accounting for depression and alcohol use. Although the effect size of these results is weak, the authors suggested that memory impairment was associated with PTSD diagnosis.

In another study, Jenkins et al.

45 examined attentional dysfunction in rape victims with (N=15) and without PTSD (N=16) relative to nontraumatized comparison subjects (N=16), using a wide range of neuropsychological tests. Subjects with PTSD performed significantly worse on all measures, including Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (p=0.001;

d=−1.79, r=−0.66), Continuous Performance Test sequential letter (p=0.01;

d=−1.06, r=−0.47), DS total (p=0.004;

d=−1.19, r=−0.50), Digit Symbol (p=0.001;

d=−1.58, r=−0.57), and the Trails B (p=0.001;

d=1.38, r=0.56). These results had strong effect size, even after accounting for depression. The authors concluded that measures of sustained and divided attention are associated with PTSD.

Bremner et al.

46 focused on verbal and visual memory in premenopausal women who were sexually abused as children. They compared results in abused women with PTSD (N=18), abused women without PTSD (N=10) and women without abuse and with PTSD (N=15). On the Logical Memory Subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale, abused women with PTSD had lower scores in verbal memory than abused women without PTSD (p=0.002;

d=−0.53, r=−0.26), with medium effect size. This deficit remained after controlling for depression and correlated with severity of PTSD and sexual abuse. Authors concluded that PTSD associated with childhood abuse is related to deficits in verbal declarative memory.

The overall result from this group of studies was conflicting, with three positive and two negative studies. No single cognitive domain was found to be consistently affected by PTSD (

Table 3).

Studies of Refugees and War Victims

The third largest group of studies evaluated in this review was of refugees and war victims, with three studies that examined neuropsychological profiles of subjects with trauma and PTSD. The average/mean age in these studies is between 37 and 78 years, and the approximate time since trauma is calculated to be between 4 and 60 years. All studies in this group found some type of cognitive impairment associated with PTSD.

Kivling-Bodén et al.

47 studied cognitive functioning in traumatized refugees with (N=21) and without PTSD (N=13) from the former Yugoslavia. They found that participants with PTSD scored significantly lower on some measures of attention, such as Picture Arrangement (p=0.01;

d=−0.93, r=−0.42); on measures of executive function, such as Figure Classification (p=0.03;

d=−0.83, r=−0.39); and on measures of visuospatial function, such as Block Design (p=0.01;

d=−1.08, r=−0.47). These measures had strong effect size; but other measures failed to show any significant differences, especially in memory, such as the Benton Visual Retention Test (p=0.15) and the Thurstone Memory Test (p=0.14). The authors reported that subjects with PTSD had significantly impaired cognitive performance.

Yehuda et al.

48 examined learning and memory by administering the CVLT in Holocaust survivors with (N=36) or without PTSD (N=26) relative to comparison subjects (N=40). The PTSD group was found to have impaired learning, with a medium effect size, as these individuals performed significantly worse than the individuals without PTSD on CVLT trials 1–5 (p<0.05;

d=−0.61, r=−0.29). However, the difference in long-delay free recall between these groups was not significant. Authors attributed impairment in verbal learning to PTSD because of accelerated cognitive decline in this older population.

Johnsen et al.

49 analyzed memory impairments in refugees from Yugoslavia, Chile, and the Middle East, both with (N=21) and without PTSD (N=21). On measures of CVLT, learning and delayed recall were impaired in the PTSD group (p=0.004 and 0.002, respectively); but after controlling for learning, they found that the group difference disappeared on all recall measures. Interestingly, when depression was controlled, all the group differences on CVLT measures disappeared. Among other neuropsychological tests, only DS Backward was impaired in the PTSD group with strong effect size (p=0.007;

d=−1.08), whereas DS Forward and Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test score results were not significant. The authors concluded that depression plays an important role in causing memory impairment in PTSD.

Although all studies in this group were positive, memory impairment was not present after controlling for depression and learning; however, there was evidence of attentional impairment in this population (

Table 3).

Studies of Survivors of Natural Disaster

There were two studies of survivors of natural disaster, and both were outside the United States. The age range of subjects is between 27 and 42 years, and time since disaster is between 9 months and 4 years.

In one of the few studies that tested cognitive function before and after trauma, Parslow et al. tested a large cohort of survivors of an extensive bush fire in Australia in 2003.

52 They compared those with PTSD (N=38) with those with subthreshold PTSD (N=606) and no PTSD (N=955) after a mean duration of 9 months posttrauma. Significant impairment was found in attention on Digit Span Backward (p<0.05;

d=−0.10, r=−0.05); Memory on CVLT (p<0.001;

d=−0.12, r=−0.06), and executive function on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (p<0.05;

d=−0.08, r=−0.04); but the effect size was weak. This cognitive impairment was associated with PTSD symptoms of reexperiencing and arousal, and these can cause impairment in verbal memory. However, poorer performance on pre-trauma neurocognitive measures was more strongly associated with posttrauma PTSD symptoms.

Eren-Koçak et al.

53 examined survivors of a 1999 earthquake in Turkey and divided them into those with current (N=11), past (N=14) and no PTSD diagnoses (N=18). After excluding subjects with depression, the authors did not find significant differences (p>0.05) on measures of visuospatial function, learning, and memory. However, they did notice executive dysfunction on Color Trail-Making Part 1 (p=0.024;

d=0.96, r=0.41) and 2 (p=0.10;

d=1.09, r=0.47), and impaired Verbal Fluency in animal names (p=0.012;

d=−0.93, r=−0.42), with strong effect size. They suggest that deficits in prefrontal organization are present, especially in individuals with current PTSD.

Although sufficient data are lacking, there is some evidence of executive dysfunction in this group (

Table 3).