Clinical Characteristics

All patients had formal medical evaluations by an internist to rule out underlying medical conditions that might have contributed to their psychiatric symptoms. The medical work-ups were consistently unremarkable. Ten patients were also evaluated by a neurologist, who found no neurologic abnormalities contributing to catatonia. Fifteen patients had brain MRIs; eight patients had head CT scans; and eight had EEGs, all with no remarkable findings.

All patient records were evaluated by the same clinician and rated for presence and severity of catatonic symptoms by use of the BFCRS.

2 The frequency of catatonic symptoms, in order of declining frequency, were as follows: immobility/stupor, 24/25; mutism, 23/25; staring, 22/25; posturing/catalepsy, 17/25; withdrawal, 16/25; stereotypy and ambitendency, 12/25; mannerism, waxy flexibility, and negativism, 10/25; rigidity and grimacing, 9/25; verbigeration and automatic obedience, 7/25; gegenhalten, 6/25; perseveration, 5/25; autonomic instability, 4/25; echophenomena and excitement, 3/25; impulsivity, combativeness, and mitgehen, 2/25; and grasp reflex, 0/25.

Eighteen patients with higher BFCRS scores (scores: 12–34) were rated as high in severity for withdrawal (including minimal intake of food), immobility, stupor, staring and posturing, resulting in inability to care for themselves. Seven patients with lower scores (scores: 6–11) presented with immobility, mutism, and staring. Although their catatonic symptoms were not rated as severe according to the symptom scale, these symptoms significantly impaired the patients' ability to care for themselves. Among the three patients with the highest BFCRS scores (34, 30, and 29), two vacillated from excitation marked by combativeness to stupor characterized by negativism and withdrawal, with little intake of food and water. The third progressed to severe immobility, muscular rigidity, catalepsy, mutism, and autonomic instability, and was transferred to a general hospital for emergency medical care and to rule out possible neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Treatment Response

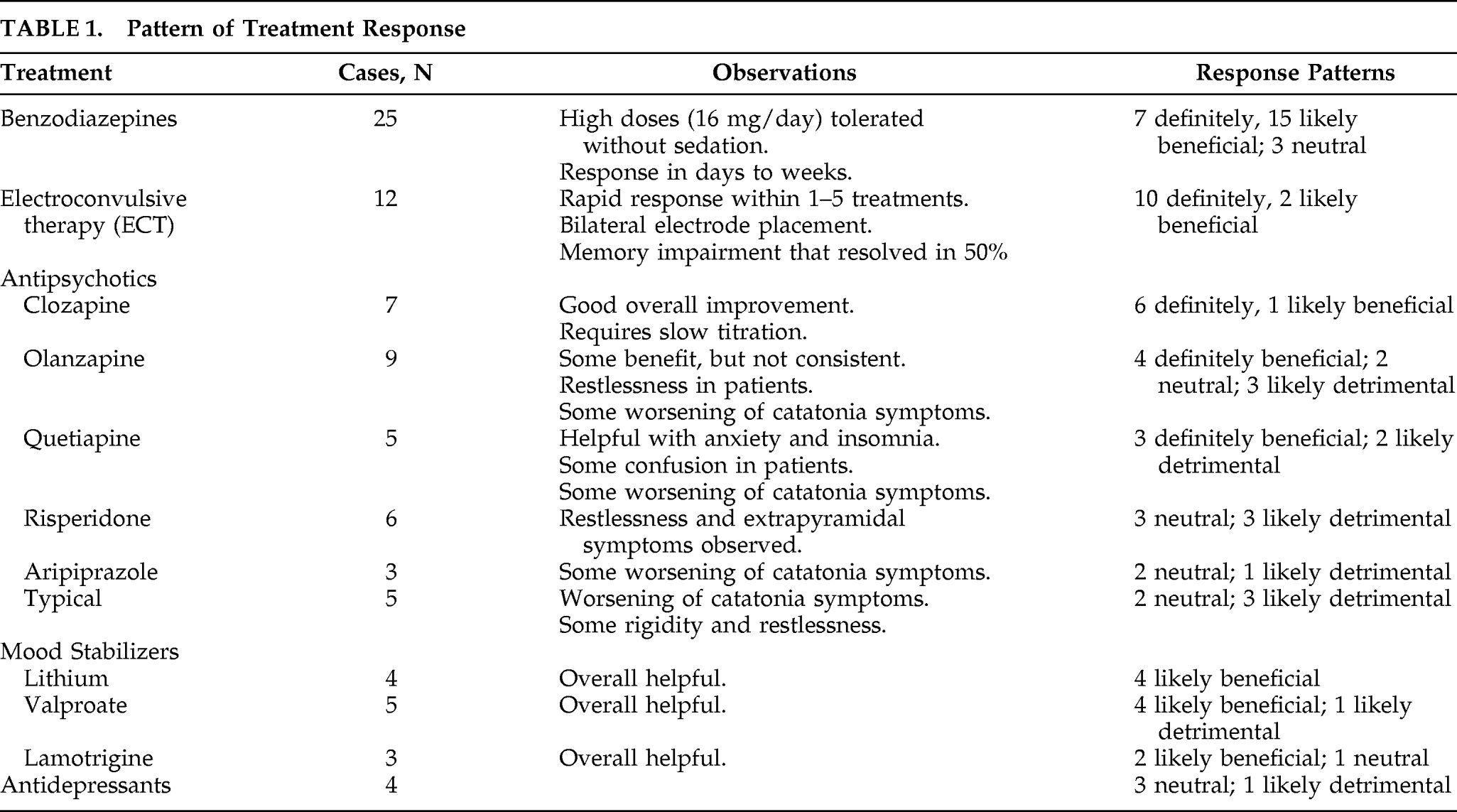

We reviewed medication administration records and correlated the clinical response to medications. Although the effects of particular treatments were often dramatic and obvious, we could not definitively attribute a clinical response to a particular treatment, since most of the patients were simultaneously on multiple treatments. Nonetheless, we examined the timing of initiation, dosage change, and discontinuation of various treatments, and categorized the treatment response patterns into the following categories: definitely beneficial, likely beneficial, neutral, likely detrimental, and definitely detrimental (

Table 1).

A total of 12 patients received ECT, with 10 receiving bilateral electrode placement. ECT led to dramatic improvement in most cases, with rapid response seen within 1–5 treatments. The response pattern showed that 10 (83%) had definite beneficial effects and 2 (17%) had likely beneficial effects, resulting in effective treatment of catatonic symptoms with a mean of 10 treatments. Six patients treated with ECT were noted to have cognitive/memory impairment during treatment, but these resolved by the time of discharge.

All 25 patients were treated with benzodiazepines. High-dose lorazepam (up to 16 mg/day) was rated as definitely beneficial for 28% of patients. The mean response time for resolving catatonia in these patients was 9 days; 68% had a “likely beneficial” response to lorazepam, whereas one did not show any response. The majority of patients required maintenance on lorazepam throughout their hospital course, including through their ECT course. While most patients had a robust response to lorazepam, some could not tolerate the higher doses, or the effects were not sustained, requiring addition of ECT or clozapine; 70% of patients were on lorazepam at time of discharge.

Seven patients were treated with clozapine, and it was rated as definitely beneficial for six of the patients and likely beneficial for one. In all cases, clozapine was initiated following unsuccessful trials of lorazepam and other atypical antipsychotic medications. While clozapine was effective, it required slow titration and close monitoring, and the response time was slower, with a mean 7-week duration for resolution of symptoms.

Although clozapine was routinely beneficial, this characteristic was not shared by other antipsychotic medications. Olanzapine and quetiapine showed mixed results, and risperidone and aripiprazole tended to have more detrimental effects. Patients treated with typical antipsychotics routinely showed detrimental effects. The adverse effects noted with these antipsychotics included worsening of catatonic symptoms, increasing confusion, agitation, and restlessness. This pattern of detrimental effects with typical antipsychotics is similar to the treatment response patterns we have reported in patients with delirious mania.

9 Twelve of the patients were also treated with mood stabilizers (lithium, valproate, lamotrigine), and all were likely beneficial during the treatment of these patients.

Patients with catatonia often presented with intense fears, perseverations, and delusional preoccupations. In 60% of our patients, we found that the treatment of catatonia was accompanied by resolution of psychotic symptoms as well, whereas 40% of these patients still had psychotic symptoms after resolution of catatonia, according to clinical notes.